Snakebite is an unusual reason for visits to Emergency Departments. This may lead to uncertainty about its treatment, and especially on the use of a very specific, expensive antidote with limited distribution and potential adverse effects.1,2 Given the potential gravity of the situation, we need to know the most appropriate therapeutic approach.3,4

We present a study of a series of clinical cases carried out in the Emergency Department of a third-level Maternity and Children's Hospital, describing the cases of snakebite reported between January 2011 and December 2013, with the aim of detecting the points that could be improved when dealing with them, in the light of their outcomes and the new recommendations.2

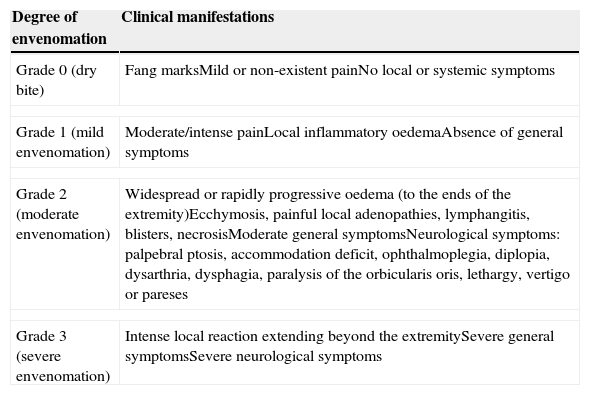

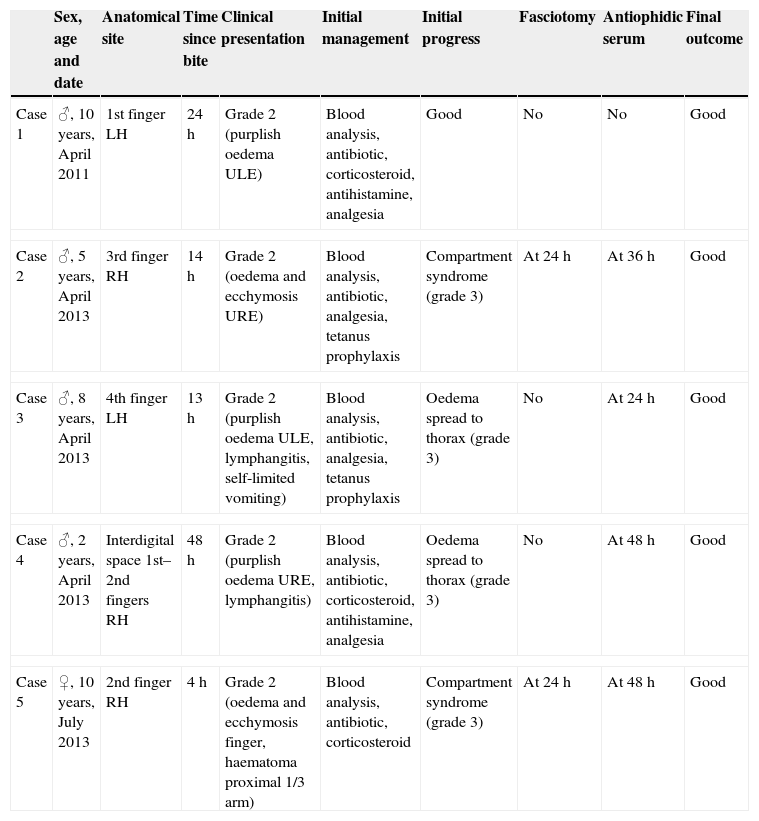

A total of five patients came for consultation, one in 2011 and the rest in 2013. All of them had previously visited another health centre and only one came to our hospital in the first 12h after being bitten. At the time of their arrival all the patients presented grade 2 envenomation. Table 1 shows the classification of symptoms after snakebite.4Table 2 lists the clinical features of the patients included in the study. The five patients were hospitalised. Blood tests were performed on all of them to rule out secondary complications, with normal results. Initially, conservative treatment was pursued. However, the four cases recorded in 2013 progressed poorly, deteriorating to grade 3, at which point the antiophidic serum (Viperfav®) was administered. Two patients required fasciotomy to be performed for compartment syndrome. The administration of the antiophidic serum did not result in adverse reactions, and the treatment brought favourable outcome. Only the case in 2011 had a favourable outcome with the initial medical treatment, without requiring antivenom.

Degree of envenomation by snakebite.

| Degree of envenomation | Clinical manifestations |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 (dry bite) | Fang marksMild or non-existent painNo local or systemic symptoms |

| Grade 1 (mild envenomation) | Moderate/intense painLocal inflammatory oedemaAbsence of general symptoms |

| Grade 2 (moderate envenomation) | Widespread or rapidly progressive oedema (to the ends of the extremity)Ecchymosis, painful local adenopathies, lymphangitis, blisters, necrosisModerate general symptomsNeurological symptoms: palpebral ptosis, accommodation deficit, ophthalmoplegia, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, paralysis of the orbicularis oris, lethargy, vertigo or pareses |

| Grade 3 (severe envenomation) | Intense local reaction extending beyond the extremitySevere general symptomsSevere neurological symptoms |

Clinical presentation and management of venomous snakebites treated in the Paediatric Emergency Department.

| Sex, age and date | Anatomical site | Time since bite | Clinical presentation | Initial management | Initial progress | Fasciotomy | Antiophidic serum | Final outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | ♂, 10 years, April 2011 | 1st finger LH | 24h | Grade 2 (purplish oedema ULE) | Blood analysis, antibiotic, corticosteroid, antihistamine, analgesia | Good | No | No | Good |

| Case 2 | ♂, 5 years, April 2013 | 3rd finger RH | 14h | Grade 2 (oedema and ecchymosis URE) | Blood analysis, antibiotic, analgesia, tetanus prophylaxis | Compartment syndrome (grade 3) | At 24h | At 36h | Good |

| Case 3 | ♂, 8 years, April 2013 | 4th finger LH | 13h | Grade 2 (purplish oedema ULE, lymphangitis, self-limited vomiting) | Blood analysis, antibiotic, analgesia, tetanus prophylaxis | Oedema spread to thorax (grade 3) | No | At 24h | Good |

| Case 4 | ♂, 2 years, April 2013 | Interdigital space 1st–2nd fingers RH | 48h | Grade 2 (purplish oedema URE, lymphangitis) | Blood analysis, antibiotic, corticosteroid, antihistamine, analgesia | Oedema spread to thorax (grade 3) | No | At 48h | Good |

| Case 5 | ♀, 10 years, July 2013 | 2nd finger RH | 4h | Grade 2 (oedema and ecchymosis finger, haematoma proximal 1/3 arm) | Blood analysis, antibiotic, corticosteroid | Compartment syndrome (grade 3) | At 24h | At 48h | Good |

LH, left hand; RH, right hand; ULE, upper left extremity; URE, upper right extremity; ♂, male; ♀, female.

The snakes that most commonly produce envenomation in the Iberian Peninsula belong to the Viperinae family (vipers).2,4,5 However, management of bites will depend on the degree of envenomation the patient shows, regardless of its aetiology.5,6

Firstly, an initial assessment will be made, using the ABCDE algorithm.6 As for specific treatment of the bite, the wound will always be cleaned and treated with antiseptic, the analgesia will be administered and the tetanus vaccination record will be checked.2,5,6 Systematic use of antibiotics is controversial and it is currently recommended to be administered only if superinfection is suspected.1,2 Similarly, the use of antihistamines and corticosteroids is not indicated, as their efficacy has not been demonstrated.1,2 The use of antiophidic serum has a particularly important place in therapeutic management. The most commonly used serum in Spain is Viperfav®. This contains heterologous proteins obtained by immunising horses.1,2,4 The classic recommendations were to reserve the use of antivenom for cases of grade 3 envenomation, due to their potential risk of anaphylaxis. However, the thorough purification process by which the serum currently available (Viperfav®) is obtained makes it a safe antidote with low allergenicity.1,2,4 For this reason, the latest treatment recommendations for venomous snakebites set forth by the Spanish Panel of Experts in December 2012 indicate early use of serum in cases of grade 2 envenomation.2,4,5 Moreover, it is considered the treatment of choice for compartment syndrome, leaving fasciotomy for cases that do not respond after administration of the antidote.2,4,5 Since the new recommendations appeared at the same time as the cases presented here, the hospital's current protocol, which did not include them, was followed in these cases. The review of the cases led to the updating of the protocol.

As regards to additional tests, a blood analysis needs to be performed to rule out associated complications such as thrombocytopaenia, fluid and electrolytic imbalances or renal insufficiency.4–6

Finally, all patients require hospital observation to monitor their progress (grade 0: 6h; grade 1: minimum 24h; grades 2 and 3: admission to hospital or Intensive Care Unit depending on severity).2,4,5

In conclusion, we want to emphasise that in 2013 we witnessed a peak of incidence of venomous snakebites in our department, as well as greater severity and poorer progress. Moreover, we have observed a tendency for patients treated conservatively to deteriorate, and therefore, in line with the new recommendations, we consider that earlier use of antiophidic serum could avoid subsequent poor progress. In addition, we have found that side effects of the antiophidic serum in the form of allergic reactions are infrequent, and that other drugs used in our patients (corticosteroids and antihistamines) did not prevent the progression of local inflammation.

Please cite this article as: Vico Andueza L, Martínez Sanchez L, Martínez Osorio J, Trenchs Sainz de La Maza V, Luaces Cubells C. Mordedura de serpientes venenosas: experiencia durante 5 años. An Pediatr (Barc). 2015;83:209–211.