Spontaneous or traumatic cranial masses are a frequent reason for seeking medical care. They are difficult to diagnose based on the findings of the history-taking and physical examination, which results in a high level of uncertainty for the clinician and the family leading to the use of imaging tests that involve ionising radiation.

Point-of-care ultrasound provides relevant information that may resolve a large part of the questions that may arise in this context.

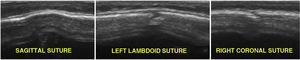

In the diagnosis of skull fractures in children, point-of-care ultrasound performed by emergency care physicians, compared to the use of computed tomography, offers a high diagnostic accuracy and can be considered useful for diagnosis of patients with closed-head injury1 (Fig. 1). In these cases, it is important to clearly establish a differential diagnosis with cephalohaematoma (Fig. 1 and Appendix A, video), which is sometimes associated with fractures, due to the differences in the presentation and outcomes of these lesions.

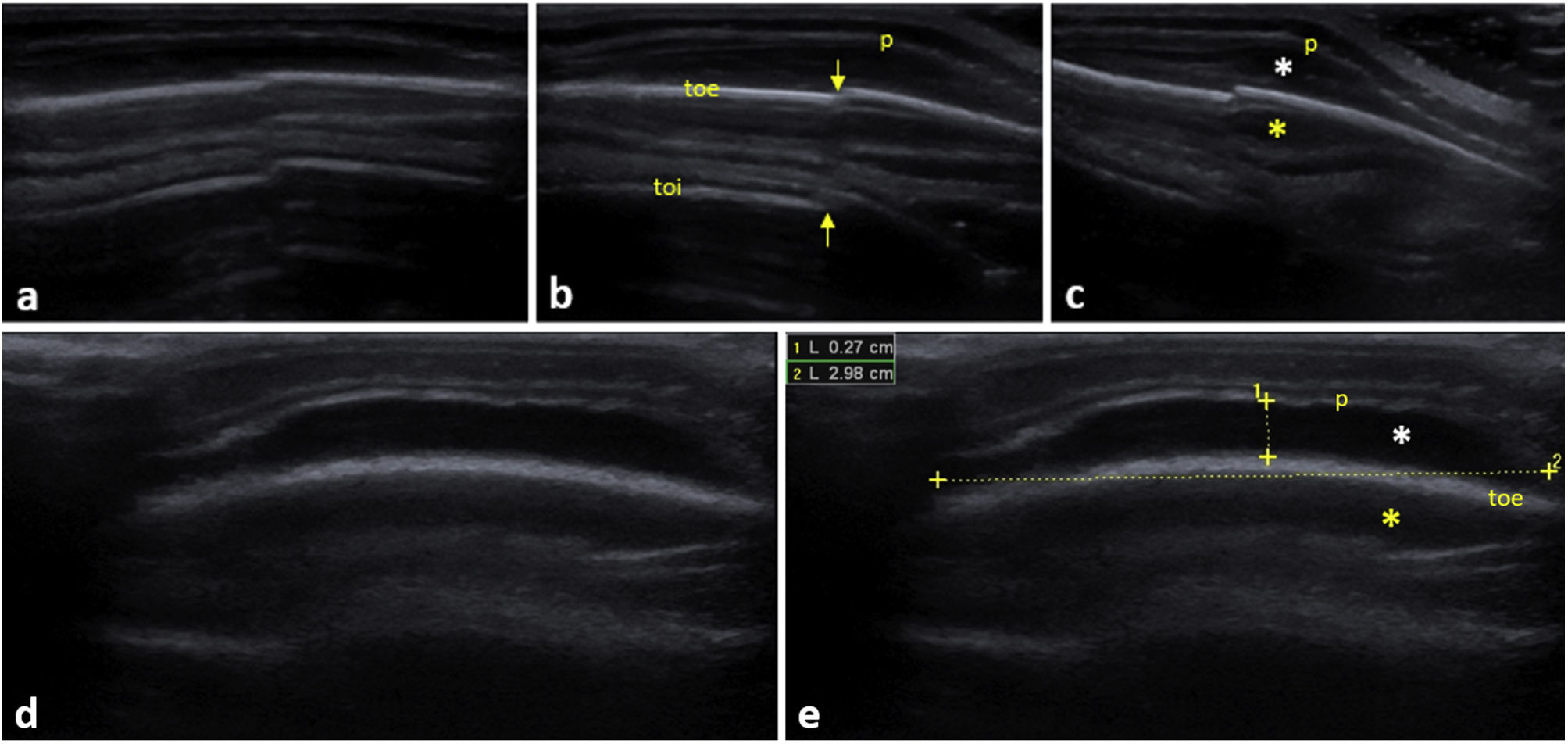

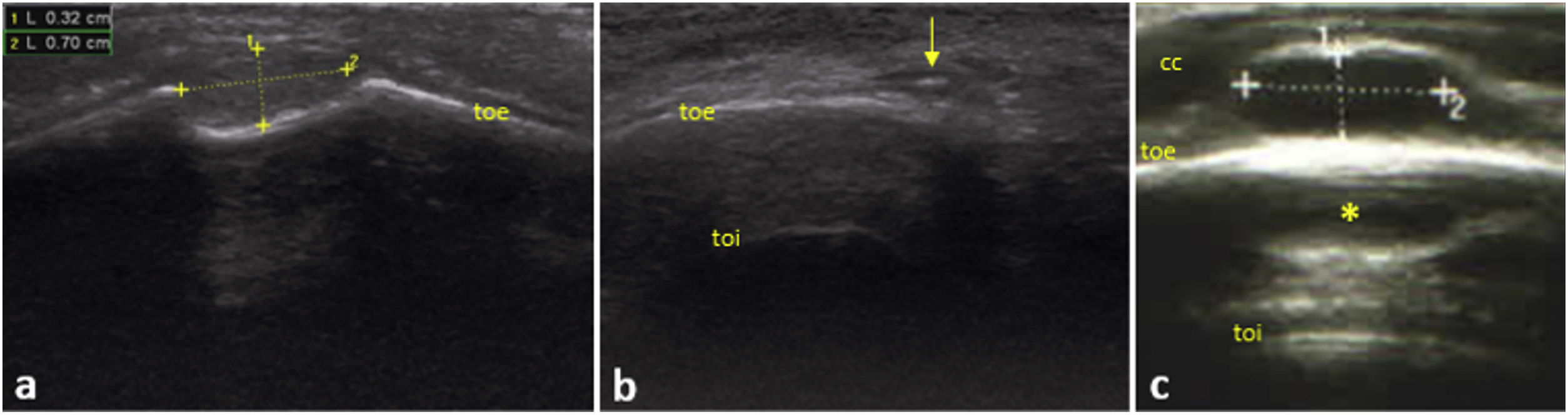

(a–c) Longitudinal scan with high-frequency linear probe (LSHFLP) on the left parietal region. Discontinuity in the cortex of both bones (arrows) suggestive of parietal bone fracture, and ipsilateral perilesional cephalohaematoma (white asterisk [*]). (d) LSHFLP at the level of a mass in the right parietal bone, which had appeared several days before in a newborn, showing cephalohaematoma with subperiosteal blood collection. (e) Scan of similar characteristics to the previous one with measurement of the length and width of the cephalohaematoma and identification of the different structures.

Yellow asterisk (*): mirror image artifact of the cephalohaematoma. p, periosteum; toe, external surface; toi, internal surface.

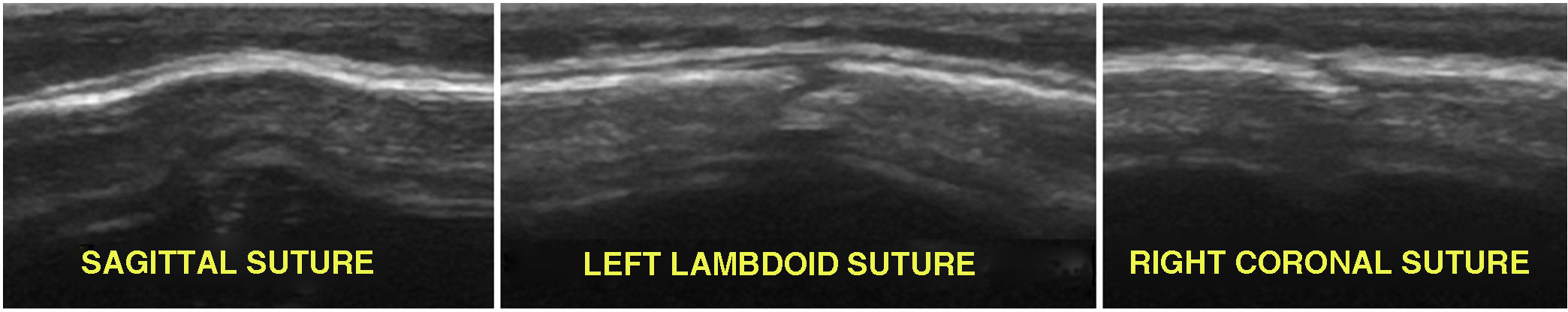

Sonography is also a useful, sensitive and specific diagnostic technique for other diseases, such as dermoid cysts,2 pilomatrixomas,3 lymphadenopathy (Fig. 2), sebaceous cysts and craniosynostosis (Fig. 3), among others.

(a) LSHFLP of a mass at the level of the left occipitotemporal suture, non-moveable and hard, in a girl aged 2 years with no reported history of trauma. Cystic appearance imprinted on the external bone surface, compatible with dermoid cyst. (b) LSHFLP of a small stony-hard mass in the right superciliary region of a boy aged 3 years: hypoechoic cystic lesion with hyperechoic centre, compatible with calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe or pilomatrixoma (arrow). (c) LSHFLP of a small, moveable slightly hard mass at the level of the right occipital region in a boy aged 3.5 years: hypoechoic cystic pattern compatible with reactive lymphadenopathy.

Yellow asterisk (*): lymph node mirror image artifact; cc, scalp; toe: external surface; toi: internal surface.

Its use as an additional tool to support the clinical diagnosis of cranial tumours could prevent misdiagnosis and help optimise the use of health care resources.

![(a–c) Longitudinal scan with high-frequency linear probe (LSHFLP) on the left parietal region. Discontinuity in the cortex of both bones (arrows) suggestive of parietal bone fracture, and ipsilateral perilesional cephalohaematoma (white asterisk [*]). (d) LSHFLP at the level of a mass in the right parietal bone, which had appeared several days before in a newborn, showing cephalohaematoma with subperiosteal blood collection. (e) Scan of similar characteristics to the previous one with measurement of the length and width of the cephalohaematoma and identification of the different structures. Yellow asterisk (*): mirror image artifact of the cephalohaematoma. p, periosteum; toe, external surface; toi, internal surface. (a–c) Longitudinal scan with high-frequency linear probe (LSHFLP) on the left parietal region. Discontinuity in the cortex of both bones (arrows) suggestive of parietal bone fracture, and ipsilateral perilesional cephalohaematoma (white asterisk [*]). (d) LSHFLP at the level of a mass in the right parietal bone, which had appeared several days before in a newborn, showing cephalohaematoma with subperiosteal blood collection. (e) Scan of similar characteristics to the previous one with measurement of the length and width of the cephalohaematoma and identification of the different structures. Yellow asterisk (*): mirror image artifact of the cephalohaematoma. p, periosteum; toe, external surface; toi, internal surface.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/23412879/unassign/S234128792400125X/v1_202404250440/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w95erwEulN6Tmh1xJpRhO+VE=)