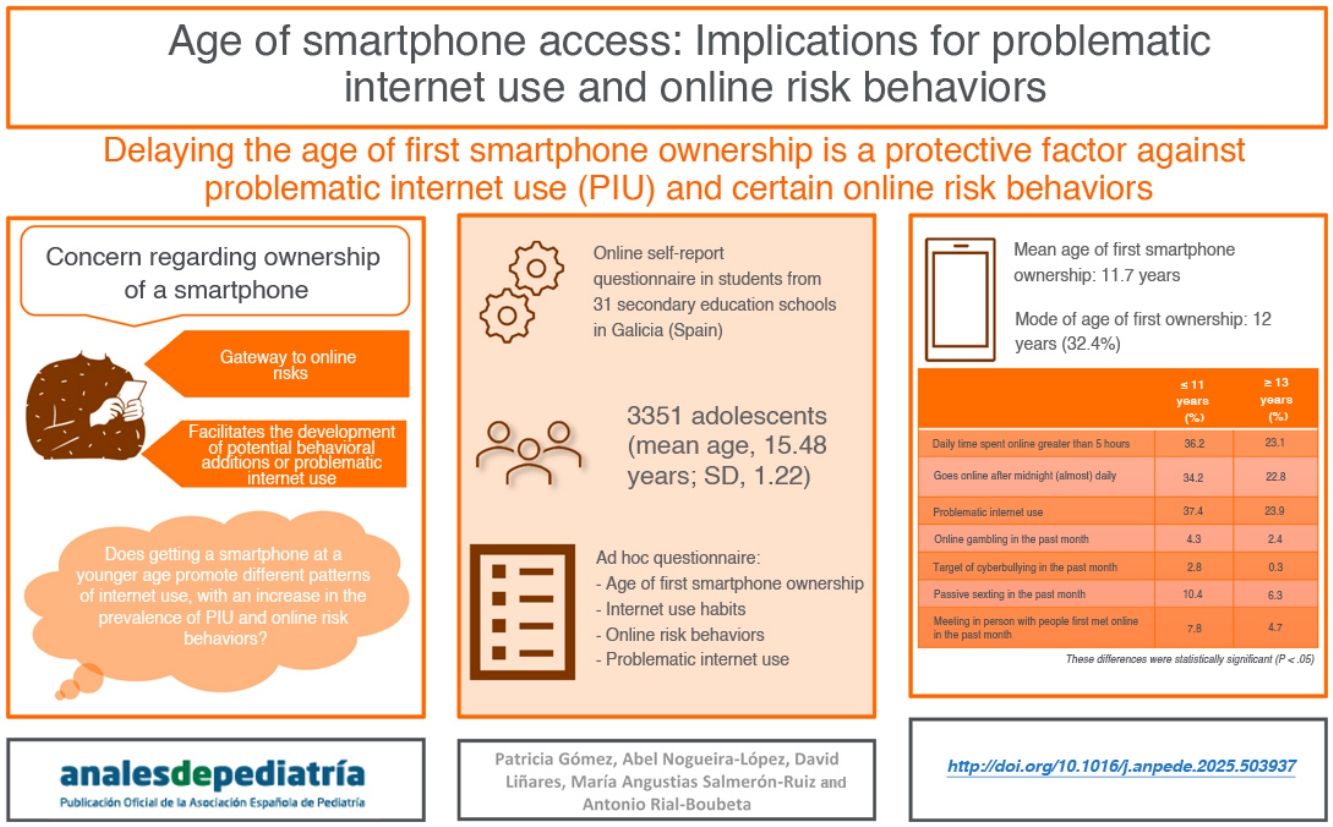

Access to smartphones raises concerns on multiple levels, particularly because it serves as a gateway to situations of online vulnerability and facilitates the development of risky behaviors, such as problematic internet use (PIU). Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze whether earlier access of children to a smartphone of their own promotes a differential pattern of internet use, with higher percentages of PIU and online risk behaviors.

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study in 31 secondary schools in Galicia (Spain). A self-administered online ad hoc questionnaire was used, including questions about the age of acquisition of the first personal smartphone, usage habits, online risk behaviors, and the Problematic Internet Use Scale in Adolescents. The final sample consisted of 3351 adolescents (mean age, 15.48 years [SD, 1.22]; 49.3% female).

ResultsThe average age at which children first got a smartphone of their own was 11.7 years. We compared the behavior of two groups: (1) those who first obtained a smartphone of their own at age 11 or earlier vs (2) those who obtained it at age 13 or later. The results showed a more frequent and intensive internet usage pattern among those who accessed smartphones earlier, with significantly higher percentages of risky behaviors, such as passive sexting, contact with strangers or online gambling, as well as nearly double the prevalence of PIU.

ConclusionsThese findings have important implications from an evidence-based prevention perspective, underscoring the pressing need to delay and rationalize the age of access to a personal smartphone during childhood and adolescence.

El acceso al smartphone preocupa a distintos niveles, especialmente por suponer una puerta de entrada a situaciones de vulnerabilidad online, y por contribuir al desarrollo de patrones de comportamiento de riesgo, como el Uso Problemático de Internet (UPI). Por ello, el objetivo de este trabajo fue analizar si el acceso más temprano a un smartphone propio favorece un patrón de uso diferencial de la Red, con mayores porcentajes de UPI y de conductas de riesgo online.

Material y métodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio transversal con 31 centros educativos de secundaria de Galicia (España). Se utilizó un cuestionario ad hoc online autoadministrado con preguntas sobre edad de acceso al primer smartphone propio, hábitos de uso, conductas de riesgo online, y la escala de uso problemático de Internet en adolescentes. La muestra final estuvo compuesta por 3351 adolescentes (M = 15,48 años; DT = 1,22; 49,3% mujeres).

ResultadosLa edad media de acceso al primer smartphone propio fue de 11,7 años. Se comparó el comportamiento de: (1) quienes accedieron a su primer smartphone con 11 años o antes y, (2) quienes accedieron con 13 años o después. Los resultados muestran un patrón de uso de la Red más frecuente e intensivo entre quienes acceden más tempranamente, así como porcentajes significativamente superiores en conductas de riesgo como sexting pasivo, contacto con desconocidos, juego de azar online… y una prevalencia de UPI que casi se duplica.

ConclusionesEstos hallazgos poseen importantes implicaciones desde el punto de vista de la prevención basada en la evidencia, urgiendo a retardar y racionalizar la edad de acceso a unsmartphone propio en la infancia y la adolescencia.

The evolution of information and communication technologies (ICTs), which at this point would be more fittingly referred to as information, communication and relational technologies (ICRTs) given their impact on social interaction,1 combined with the massive irruption of smartphones, has fostered the currently pervasive use of screens by generation Z. This generation has firsthand knowledge of the benefits of digitalization, although they cannot fully enjoy these advantages, for the developing brain of its members makes them more vulnerable to some of the associated drawbacks, such as digital distractions, risks and harmful effects, decreased security for their personal data or excessive use.2

Although it is important to avoid overpathologizing these behaviors, given that frequent or intensive screen use is not considered a pathological condition in and of itself,3 different organizations, pediatric societies and authors have expressed concern about the potential risks that these behaviors pose to the health and development of children and adolescents.4–6 This has motivated the development of plans to address this phenomenon at the national level, such as the Family Digital Plan developed by the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Pediatrics) and endorsed by the Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (Spanish Data Protection Agency).7

On the other hand, the age at first use is one of the strongest predictors supported by the scientific evidence in the field of substance abuse,8,9 and it is known that earlier initiation of use is associated with more persistent risk behaviors and a greater deleterious impact on health.10,11 This association has also been investigated in behavioral addictions not involving substances, and the evidence shows, for instance, that the adolescents with the most serious online gambling and betting problems are precisely those who started these activities at earlier ages.12 Similarly, secondary education students with onset of weekly internet use at a young age are more likely to develop problematic internet use (PIU) and spend more time online.13 In addition, problematic gaming was associated with an earlier onset of weekly gaming.14

When it comes to the age of first ownership of a smartphone, the evidence is still limited and the results inconsistent.15 However, as clinicians and researchers alike keep stressing, the absence of evidence on an association should not be confused with evidence of the absence of such an association.16

In addition, having a smartphone of one’s own also opens the door to online risks, which the youngest users may be less equipped to handle, such as grooming,17 cyberbullying,18 sexting,19 online gambling20 or sexist, misogynistic, homophobic, racist, xenophobic, aporophobic and pornographic content,21 among others. What does seem clear is that, among other things, the amount and quality of the content consumed by children and adolescents and the balance with other activities can have a positive or negative impact on their development.22

In this context, given the scarcity and inconsistency of the current evidence and the fact that families and institutions have to make decisions regarding this issue, there is a pressing need for empirical evidence on the possible impact of early smartphone ownership. Therefore, the objective of our study was to analyze whether acquiring one’s first smartphone at a young age can increase the probability of PIU and a higher screentime and promote the development of online risk behaviors during adolescence.

Material y methodsParticipantsWe used purposive sampling to select participants among compulsory (ESO) and noncompulsory (bachillerato) secondary education and vocational education students in Galicia (Spain). A total of 31 schools participated in the study (12 public schools and 19 publicly subsidized private schools). The initial sample comprised 4439 adolescents (aged 12–18 years), of who 95.7% reported having a smartphone of their own. We excluded 417 adolescents due to an excess of missing data, incoherent answer patterns or not owning a smartphone, and 671 due to narrowing the age range to 14–18 years to allow comparison with the sample of ESTUDES, a survey on drug use in secondary education students in Spain conducted biennially in the framework of the Plan Nacional sobre Drogas (PNSD, National Plan on Drugs). The final sample consisted of 3351 adolescents (mean age, 15.48 years [SD, 1.22]; 49.3% female).

InstrumentWe collected the data using an ad hoc questionnaire organized in four sections. The first section was for collection of sociodemographic data (age, sex, school year and school); the second included items regarding the age of first ownership of a mobile phone with internet access (smartphone) and the online access frequency, amount and activity. The following section assessed online risk behaviors, such as active sexting (sending explicit [of a sexual/erotic nature] photos or videos of oneself through the internet or smartphone to someone else), passive sexting (receiving explicit photos/videos of themselves from a contact through the internet or smartphone), sextortion, contact with strangers and online gambling. The last section consisted of a Spanish scale for screening PIU in adolescents (EUPI-a, Escala de Uso Problemático de Internet en Adolescentes23), with a threshold of 16 points for the presence of PIU. The instrument exhibited a good internal consistency in our study (α = 0.89).

ProtocolWe collected data through an online self-report questionnaire that students self-administered from school. Students, teachers and parents (or legal guardians) were appropriately informed about the purpose of the study, participation in the study was voluntary, anonymous and confidential. We secured the collaboration and obtained consent from both the management of the schools and the corresponding parent associations (PAs). The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Universidad de Santiago de Compostela (USC-52/2021).

Data analysisAfter cleansing the data, we conducted a descriptive analysis of the sample and the age at ownership of the first smartphone (overall and by sex with the Student t test). We also calculated the prevalence, frequency, and time spent using the smartphone use in general, as well as the overall prevalence of PIU. Next, we divided the sample into three subgroups based on the age of first smartphone ownership to assess the potential impact of earlier access, using the mode of the age of first access in the sample as reference to establish the groups for comparison. We analysed the distribution of the three groups in terms of sex (χ2) and age (F) and then compared two of the groups (early vs late access) in terms of their internet use habits, PIU and online risk behaviors (using the χ2 to compare proportions and the Student t test to compare means). We also calculated the contingency coefficient (CC) and Cramer’s V to estimate the effect size. Last of all, we performed an analysis of covariance to attempt to isolate the effects of age and sex on PIU. All the analysis was conducted with the IBM SPSS Statistics statistical software suite, version 25.24

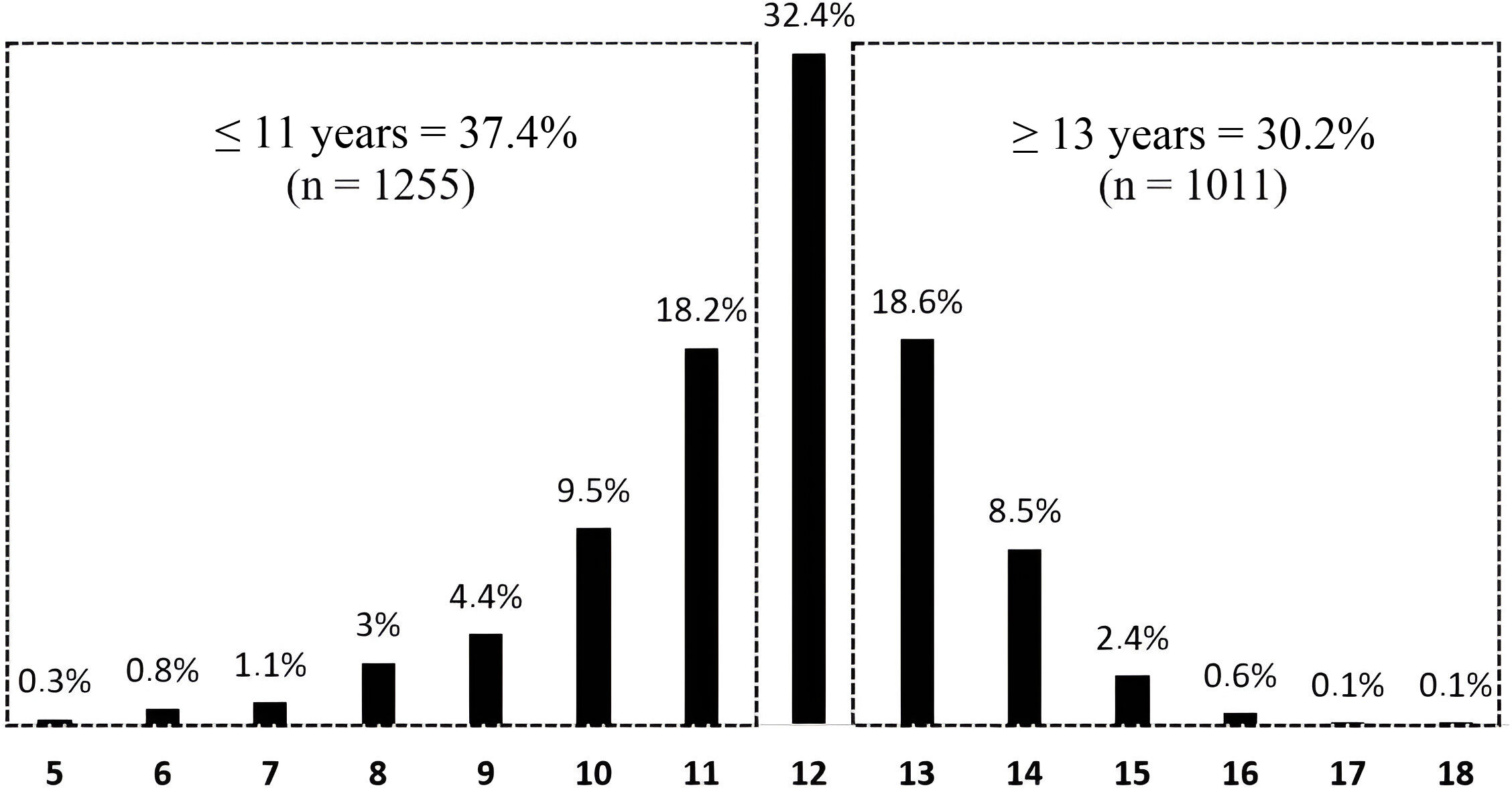

ResultsThe mean age at which participants first had access to a smartphone of their own was 11.70 years (SD, 1.712). The mode of the age of was 12 years (32.4%), while 37.4% owned a smartphone at age 11 years or younger (early access group), and 30.2% at 13 years or older (late access group) (Fig. 1). Girls reported first ownership at a slightly younger age compared to boys (11.61 vs 11.80 years; t = −3.170; P = .002).

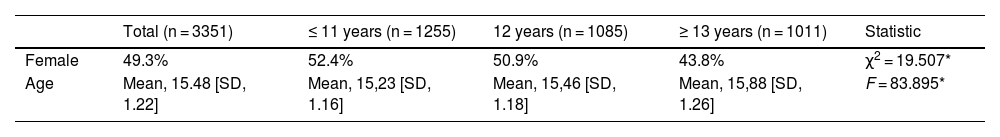

Smartphone use was widespread: 92.6% of the total sample reported using it daily, with 29% using it more than 5 h a day. The overall prevalence of PIU was 31.4%. On the other hand, in the group of adolescents with early access, there was a significantly higher proportion of girls (52.4%) compared to the group with access at 12 years (50.9%) and the group with late access (43.8%) (χ2 = 19.507; P = .001). In addition, the mean current age was significantly lower in the groups with earlier access (early access,15.23; access at age 12 years, 15.46; late access, 15.88) (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of the sample, overall and by age of first smartphone ownership.

| Total (n = 3351) | ≤ 11 years (n = 1255) | 12 years (n = 1085) | ≥ 13 years (n = 1011) | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 49.3% | 52.4% | 50.9% | 43.8% | χ2 = 19.507* |

| Age | Mean, 15.48 [SD, 1.22] | Mean, 15,23 [SD, 1.16] | Mean, 15,46 [SD, 1.18] | Mean, 15,88 [SD, 1.26] | F = 83.895* |

*P < .001.

When we compared the early access group (at 11 years or younger) and the late access group (at 13 years or older), we found statistically significant differences in all internet use habits under study (Table 2). In our sample, getting the first smartphone at age 11 years or younger was associated with going online more frequently and longer daily screen times. Adolescents who had smartphones at a younger age exhibited more intensive use patterns, with 36.2% spending more than 5 h a day online, and were more likely to exhibit risk behaviors, such as keeping the smartphone in the bedroom at night daily or almost daily (81.2% vs 67.9%) or going online after midnight every day (34.2% vs 22.8%). Similarly, they were more likely to take the smartphone to school and use it during school hours and used social media more, and most of them (73.5%) had accounts on three or more social media platforms.

Internet use habits.

| Total (n = 3351) % | ≤ 11 years (n = 1255) % | ≥ 13 years (n = 1011) % | χ2 | CC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of going online | Never or rarely | 0.9 | 1 | 1.5 | 20.545** | 0.095 |

| A few times a month | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.9 | |||

| A few times a week | 5.1 | 3.8 | 7.4 | |||

| Daily or almost daily | 92.6 | 94.3 | 89.2 | |||

| Time spent online each day | Less than 1 h | 4.9 | 4 | 6.3 | 55.115** | 0.154 |

| 1−2 h | 16.3 | 14.4 | 20.9 | |||

| 2−3 h | 25.7 | 23.3 | 27.2 | |||

| 3−5 h | 24.1 | 22.2 | 22.5 | |||

| More than 5 h | 29.0 | 36.2 | 23.1 | |||

| Keeping smartphone in bedroom at night | Never or rarely | 13.2 | 7.8 | 19.1 | 71.350** | 0.175 |

| A few times a month | 4.3 | 3.7 | 5 | |||

| A few times a week | 7.5 | 7.3 | 8 | |||

| Daily or almost daily | 75.0 | 81.2 | 67.9 | |||

| Going online after midnight | Never or rarely | 18.0 | 12.5 | 24.3 | 78.020** | 0.182 |

| A few times a month | 14.6 | 12.7 | 16.7 | |||

| A few times a week | 38.8 | 40.6 | 36.1 | |||

| Daily or almost daily | 28.6 | 34.2 | 22.8 | |||

| Taking the smartphone to school | Never or rarely | 16.0 | 12 | 20.9 | 35.699** | 0.125 |

| A few times a month | 6.3 | 7 | 6 | |||

| A few times a week | 8.3 | 9.3 | 6.7 | |||

| Daily or almost daily | 69.4 | 71.7 | 66.4 | |||

| Using the smartphone during school hours | Never or rarely | 57.9 | 53.3 | 61.3 | 15.089* | 0.081 |

| A few times a month | 10.9 | 12.2 | 9.4 | |||

| A few times a week | 17.9 | 19.5 | 17 | |||

| Daily or almost daily | 13.3 | 15 | 12.3 | |||

| Having accounts in at least 3 social media platforms | 66.5 | 73.5 | 57.1 | 66.478** | 0.170 |

Abbreviation: CC, contingency coefficient.

*P < .05; **P < .001.

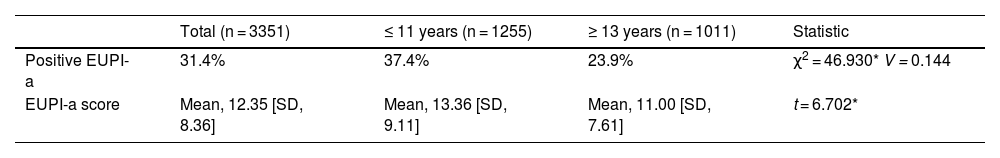

Through the administration of the EUPI-a questionnaire, we found a statistically greater proportion of adolescents that were starting to exhibit potentially problematic or harmful online activity in the group that had their first smartphone at age 11 or younger (Table 3). Still, to attempt to isolate the potential differential effect of getting the first smartphone at an early age, we performed an analysis of covariance. The results evinced a significant effect of smartphone ownership at a young age (F = 45.12; P < .001) beyond the effects of sex (F = 26.36; P < .001) and current age (F = 9.09; P < .01).

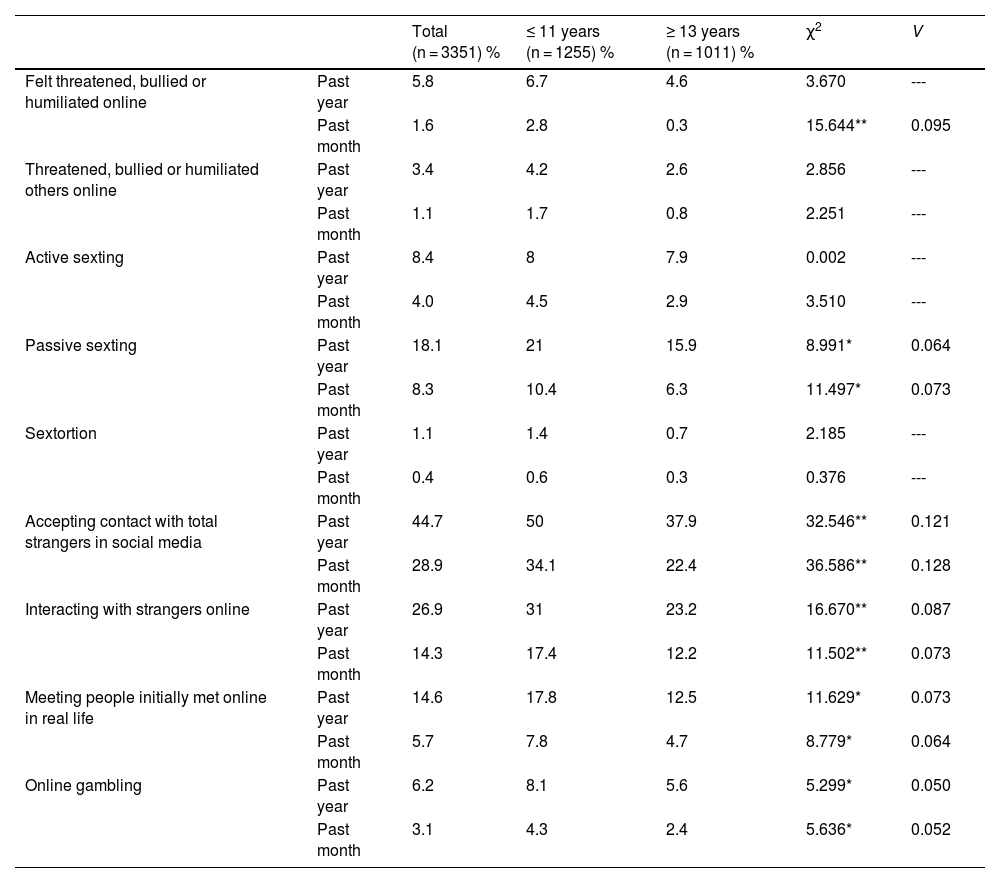

As can be seen in Table 4, getting the first smartphone at younger ages is associated with a significantly higher prevalence of some online risk behaviors, such as passive sexting, contact with strangers or online gambling. In addition, we found greater proportion of possible victimization from cyberbullying in association with having a smartphone at age 11 years or younger.

Online risk behaviors.

| Total (n = 3351) % | ≤ 11 years (n = 1255) % | ≥ 13 years (n = 1011) % | χ2 | V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Felt threatened, bullied or humiliated online | Past year | 5.8 | 6.7 | 4.6 | 3.670 | --- |

| Past month | 1.6 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 15.644** | 0.095 | |

| Threatened, bullied or humiliated others online | Past year | 3.4 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 2.856 | --- |

| Past month | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 2.251 | --- | |

| Active sexting | Past year | 8.4 | 8 | 7.9 | 0.002 | --- |

| Past month | 4.0 | 4.5 | 2.9 | 3.510 | --- | |

| Passive sexting | Past year | 18.1 | 21 | 15.9 | 8.991* | 0.064 |

| Past month | 8.3 | 10.4 | 6.3 | 11.497* | 0.073 | |

| Sextortion | Past year | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.185 | --- |

| Past month | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.376 | --- | |

| Accepting contact with total strangers in social media | Past year | 44.7 | 50 | 37.9 | 32.546** | 0.121 |

| Past month | 28.9 | 34.1 | 22.4 | 36.586** | 0.128 | |

| Interacting with strangers online | Past year | 26.9 | 31 | 23.2 | 16.670** | 0.087 |

| Past month | 14.3 | 17.4 | 12.2 | 11.502** | 0.073 | |

| Meeting people initially met online in real life | Past year | 14.6 | 17.8 | 12.5 | 11.629* | 0.073 |

| Past month | 5.7 | 7.8 | 4.7 | 8.779* | 0.064 | |

| Online gambling | Past year | 6.2 | 8.1 | 5.6 | 5.299* | 0.050 |

| Past month | 3.1 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 5.636* | 0.052 |

Abbreviation: V, Cramer V.

**P < .001.

With respect to other analyzed online risk behaviors (cyberbullying others, engaging in active sexting or being subject to sextortion), we did not find statistically significant differences, although we did find an increasing trend with higher percentages among those who had their first smartphone at an early age.

DiscussionThe aim of the study was to analyze the potential impact of having a smartphone of one’s own at an earlier age. To this end, we analyzed the frequency of going online and the amount of time spent online, the type of online activity, PIU and online risk behaviors in adolescents aged 14–18 years, comparing those who got their first smartphone at age 11 years or younger to those who got it at age 13 years or older.

The scientific evidence to date has shown that earlier onset of any form of substance use is associated to a higher prevalence and riskier patterns of use in the medium term8–10 and, while the etiology and particular characteristics of substance abuse may differ, some of the principles or assumptions that apply to substance abuse may also be applicable to behavioral additions that do not involve drugs. In this regard, the National Strategy on Addiction for 2017–2024 in Spain25 included delaying the age of onset of substance use for all substances, an objective that could be extrapolated to the addictions that do not involve substances currently recognized in diagnostic manuals (internet gaming disorder, online gambling disorder) and PIU. This is why it is also crucial to take into account the age at which children get their first smartphone of their own, as this is the device used most frequently to access the internet and for online gaming or gambling.26

In our study, the mean age at first smartphone ownership 11.70 years, with a younger age for female adolescents. The mean age was slightly greater compared to the ages reported by a large part of the previous studies conducted in Spain.27,28 However, it is worth noting that this variable is affected by the age range of the studied sample and the type of electronic device. Thus, in a sample of children aged 9–16 years, Garmendia et al.29 found an age at first ownership of a mobile phone without internet access of 10.40 years and an older age of first smartphone ownership of 11.80 years. The fact that a large public database like the site of the National Plan on Drugs (PNSD) does not provide specific data on the age of first smartphone ownership led us to restrict our analyses to the 14-to-18 years age group to allow comparisons with the ESTUDES survey.

Adolescents who owned their first smartphone at an earlier age went online more frequently and spent more time online, and a higher proportion of this group exhibited PIU, went online after midnight and kept the smartphone in their bedrooms at night. These findings are consistent with the sleep disturbances and unhealthy sleep habits that are among the most widely reported consequences of maladaptive internet use in the scientific literature.30,31 This is particularly concerning because healthy sleep during childhood and adolescence is crucial for healthy development in every area.32 In this regard, and based on the most recent evidence, international guidelines recommend that caregivers in the household remove all electronic devices from the bedrooms of children and/or adolescents and model healthy behavior.33

The age at which children get smartphones of their own is also considered a relevant concern because these devices could be a gateway for certain online risk behaviors, such as online gambling, sexting, sextortion, cyberbullying, contact with strangers etc.34 In our study, we observed a consistent pattern of increased prevalence of these behaviors among students who got their first smartphone at age 11 or younger, with statistically significant increases for online gambling, passive sexting, coming into contact with strangers and experiencing cyberbullying. If we interpret this information in the context of the findings of the EU Kids Online survey35 (which was conducted in 19 European countries and showed that Spain was the country with the largest proportion of adolescents that reported that they did not know how to react to the online behaviors of others that they did not like), it is reasonable to assume that smartphone use at an early age could be a source of problems at a point in life when the brain is still maturing and young people lack the necessary skills and resources to cope with them. Skills and resources that they are more likely to have developed, along with greater resilience, by the end of adolescence through learning and maturation.36

Last of all, we ought to comment on the limitations of our study. Chief among them is the lack of randomization in sample selection, which limits the external validity of our findings. In addition, the cross-sectional design did not allow us to analyze causal relationships between the variables under study. Thirdly, the differences in the sex and age distributions of the groups that were compared could explain the observed differences to some degree, which led us to perform an analysis of covariance. Its results allowed us to identify an effect of age of first ownership beyond those demographic differences. At any rate, only a longitudinal design combined with appropriate methodology would allow the interpretation of the observed differences in terms of causality. Last of all, the use of self-report measures may have affected the accuracy of the calculated percentages and prevalence values, as the reported data may have led to under- or overestimation due to psychological biases in participants. However, several experts in the field of addiction37,38 have demonstrated that these measures are as valid and reliable as other methods for assessing the extent of substance use, so it would be reasonable to expect that this would also be the case for behavioral addictions not involving substances.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, while our intent is not to stigmatize smartphone use or overpathologize associated behaviors,3,39,40 our findings support the hypothesis that creating conditions that enable excessive exposure of children and/or adolescents to online content and activity from an early age, when they do not have the skills, maturity and emotional support required to handle it, may have a deleterious impact. Our study found that, regardless of sex, adolescents who owned smartphones at an earlier age exhibited a different pattern of online activity characterized by more frequent and longer use of the smartphone, poorer digital hygiene (use at night and during school hours) and higher prevalences of PIU and online risk behaviors. In consequence, we underscore the need to delay the age of first smartphone ownership, and urge health care professionals, especially those who work in pediatric and primary care settings or health prevention and education, to be proactive in providing guidance to families. Education and training programs are also needed to help all involved parties understand the benefits and drawbacks of early first smartphone ownership, along with the implementation of strategies promoting healthy use of these devices. The data are also relevant for the development of preventive policies, which should always take into account empirical evidence and be led by a strong sense of social responsibility. The recent evidence allows us to state that we are facing a public health problem6 with important repercussions at different levels that calls for a high level of social responsibility from the community as a whole, starting with the health and education systems and the families themselves. At this moment in history, when there is considerable controversy and social concern, delaying and optimizing the age at first smartphone ownership should be considered a necessary measure.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.