Antibiotic resistance is a major threat to global health. Optimizing the use of antibiotics is a key measure to prevent and control this problem. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASPs) are designed to improve clinical outcomes, minimize adverse effects and protect patients, and to ensure the administration of cost-effective treatments. Inappropriate use of antibiotics also occurs in pediatric clinical practice. For this reason, ASPs should include specific objectives and strategies aimed at pediatricians and families. Implementing these programs requires the involvement of institutions and policy makers, healthcare providers as well as individuals, adapting them to the characteristics of each healthcare setting. Pediatric primary care (PPC) faces specific issues such as high demand and immediacy, scarce specialized professional resources, difficulties to access regular training and to obtain feedback. This requires the design of specific policies and strategies to achieve the objectives, including structural and organizational measures, improvement of the information flow and accessibility to frequent trainings. These programs should reach all health professionals, promoting regular trainings, prescription support tools and supplying diagnostic tests, with adequate coordination between health care levels. Periodic evaluations and surveillance tools are useful to assess the impact of the actions taken and to provide feedback to health providers in order to adapt and improve their clinical practice to meet ASPs objectives.

La resistencia a antimicrobianos supone una amenaza para la salud pública a nivel mundial. Su estrecha relación con el consumo de antibióticos hace necesaria la adopción de medidas para optimizar su uso. Los Programas de Optimización del Uso de Antibióticos (PROA) se diseñan para mejorar los resultados clínicos de los pacientes con infecciones, minimizar los efectos adversos asociados a su uso y garantizar la administración de tratamientos costo-eficientes. En la práctica clínica pediátrica el uso inadecuado de antibióticos es una realidad. Es por ello que los PROA deben incluir objetivos y estrategias específicos dirigidos a familias y pediatras. La implementación de estos programas requiere la implicación de instituciones, profesionales y población, adaptándolos a las características de cada ámbito asistencial. La atención primaria (AP) pediátrica presenta unas peculiaridades organizativas y asistenciales (hiperdemanda e inmediatez, escasos recursos profesionales especializados, dificultades en el acceso a la formación continuada y a la retroalimentación informativa) que exigen el diseño de medidas y estrategias propias para conseguir los objetivos fijados, que incluyan medidas estructurales, organizativas, de flujo de información y de formación continuada. Es necesario que estos programas alcancen a todos los profesionales, abordando la formación continuada, las herramientas de apoyo a la prescripción y el acceso a pruebas diagnósticas, con la adecuada coordinación interniveles. Se debe evaluar periódicamente el impacto de las distintas acciones en los objetivos planteados. La información generada debe revertir a los profesionales para que puedan adaptar su práctica clínica a la consecución óptima de los objetivos.

The increase in antimicrobial resistance associated with the excessive use of these drugs poses a threat to public health,1,2 so the establishment of antibiotic stewardship programmes (ASPs) is of the essence.3,4 There is evidence that reducing antimicrobial consumption improves antimicrobial susceptibility.5 In recent years, there has been a decreasing trend in the consumption of antibiotics in Spain,6 although it continues to be high compared to other European countries.7 Ninety-two percent of prescriptions are made at the primary care (PC) level,8 although part of this percentage may represent induced prescriptions (written by PC providers for drugs initially ordered at a different level of care).

There are no official nationwide figures on the consumption of antibiotics in the paediatric population in Spain, although there is evidence suggesting that it is also high,9 especially in children aged less than 3 years.10 In the field of paediatrics, antibiotic prescribing has decreased,11 in part due to the introduction of rapid microbiological diagnosis techniques12–15 and the implementation of delayed prescription strategies (contingent on the course of the disease) in select cases.16 Prescription patterns have also improved, with a decrease in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics,11 although there is still room for improvement.17,18

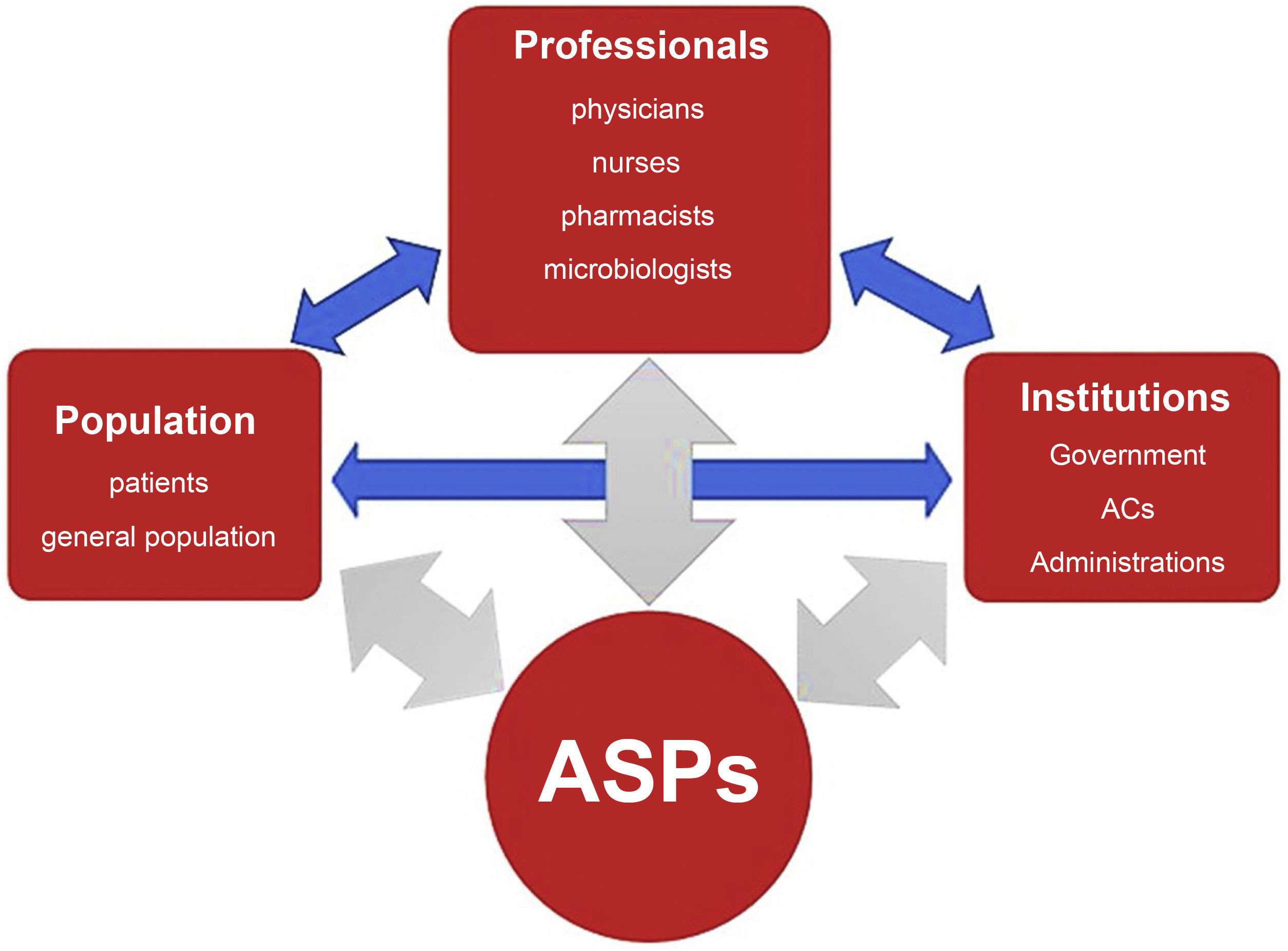

Antimicrobial stewardship programsDefinition and general objectives of ASPsThe goal of ASPs is to improve outcomes in patients who require antibiotherapy, minimise its adverse effects, control the development of drug resistance and guarantee the use of cost-effective treatments. They involve institutions, health care providers and the population (Fig. 1) and interactions between them, and need to be adapted to the particular characteristics of each care setting.19

ASPs in primary careThe following must be taken into account:

Characteristics of the care setting19–21- •

Continuity of care, to allow a better understanding of patients and their environment.

- •

Possibility of intervention at individual and community levels through prevention and promotion activities.

- •

Large caseloads and high-frequency users,22 which limit the time that can be devoted to each patient, health education and activities other than patient care.

- •

Variability in the access to rapid diagnostic tests and in the performance and turnaround time of other microbiological tests.23

- •

Imposed duty to take on prescriptions ordered by other providers or in other care settings.

- •

Absence of clinical decision support tools (CDSTs) integrated in the electronic health record (EHR) system (algorithms, alerts in response to inappropriate prescription).

- •

There are numerous distinct management structures (administrations, health care areas, health care districts, primary care centres) that are organised differently.

- •

Lack of consistency between different health care areas in the antimicrobial guidelines used as reference.

- •

Differences in health care resources between rural and urban settings.24

- •

Geographical isolation and dispersion of PC paediatricians, hindering access to training activities and the exchange of information between professionals.

- •

Variability in the offering and access to continuing education activities, which do not always meet the needs of health care professionals.

- •

Important barriers in the launching, implementation and participation in research projects due to professional isolation, heavy workloads, bureaucratic obstacles and regulations that are not adapted to the characteristics of PC.

In 2014, the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System of Spain established the national plan against antibiotic resistance (PRAN: Plan Nacional frente a la Resistencia a los Antibióticos) with the aim of reducing the risk of selection and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant strains and their impact on human and animal health, and preserving the efficacy of existing antibiotics sustainably. The most recent update to the plan was made in 2022.6

The PRAN establishes the need to launch initiatives to promote the rational use of antibiotics, giving rise to ASPs in hospital and community settings. These programmes must be developed at the initiative of the institution and adapted to the circumstances under which it carries its health care activity, its needs and its established priorities. Table 1 details the competencies, levels of action and coordination between different institutions.

Regulatory framework for the development and operation of antimicrobial stewardship programmes/teams.

| Scope | Responsible authority | Description |

|---|---|---|

| National | 1. Ministry of Health/AEMPS | Nationwide coordination:

|

| Regional (AC) and local (health care facilities and institutions) | 2. Autonomous communities (regional public health system authorities) | Each AC will appoint regional representatives responsible for the coordination and implementation of ASPs in hospitals and PC centres, with the following minimum requirements:

|

| Regional (AC) and local (health care facilities and institutions) | 3. Local level (health care area management/administration / hospital management / health care quality structures) | Local level (institutions):

|

AC, autonomous community; ASP, antimicrobial stewardship programme.

Antibiotic stewardship programmes at the community level require:

- •

An institutional initiative, with the creation of a committee for the optimization of antimicrobial use in the framework of the corresponding organizational structure, and its characteristics should be tailored to the particularities of the health care system in each autonomous community (AC).

- •

The establishment of effective coordination between levels of care: hospitals and primary care centres: hospitals and social services and health care centres.

- •

Be adapted to the particular characteristics of the setting.

- •

Be organised around multidisciplinary teams that included adult and paediatric PC providers and other specialities involved in the diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases and the use of antimicrobials.

- •

The support of the administration-management of the corresponding health care area, which is responsible for providing the necessary resources for the implementation of the planned activities.

At the PC level, the ASP programme must include specific objectives and indicators for paediatric care.

Based on the pursued outcomes, ASPs can be categorised as:

- •

Basic ASP: measures that should be implemented by every professional in every team and health care area.

- •

Advanced ASP: measures recommended in centres that have longer experience implementing these programmes.

- •

ASP of excellence: measures to apply in reference centres in the area.

It is important that any designed strategies or interventions involve both the entire collective and specific professionals, so they should be included in the management and operations agreement and promoted at the level of teams and individual professionals.25

Primary care ASP teams: Members and scope of activityThe ASP team must be established formally, defining an organizational structure: members, strategies, interventions and evaluation. It must meet periodically and produce an annual report.

The team must include, in addition to a family physician, an emergency physician (hospital/out-of-hospital), at least one PC paediatrician, a microbiologist and a primary care pharmacist, as well as a representative of the administration/management. Whenever possible, it should also include other professionals (nurses, paediatric odontologists) on a temporary or permanent basis. The microbiologist is responsible for contributing local data on drug resistance in the microorganisms isolated most frequently in paediatric samples in the community at regular intervals, participating in the training plans for health care professionals on sample collection, storage and transport, the interpretation of microbiological results and antimicrobial susceptibility testing, the indications for ordering point-of-care diagnostic tests, their use and interpretation, while on the other hand gathering information on the concerns, questions and suggestions of PC professionals. An antimicrobial susceptibility testing scheme must be agreed on by the PC system and the reference laboratory.26 The pharmacist is responsible for contributing data on antimicrobial consumption and discussing the relevant indicators, their meaning, their magnitude and their temporal trends.

To establish in coordination the criteria for the initiation and selection of antibiotherapy in the management of the most prevalent community-acquired paediatric diseases as well as referral criteria, independently of the level of care where the patient is managed, hospital and primary care ASP teams must include paediatricians working in each of these care settings (preferably including an emergency care paediatrician).

In the implementation of ASPs, specific human resources must be allocated to the program and its activities included in the schedules of participating professionals. The programme must be provided with the necessary information and technology resources, ensuring access to every professional.

Depending on its capabilities, each primary care centre/clinical management team or equivalent structure will designate an antimicrobial stewardship point person to facilitate the bidirectional communication between the committee/ASP team and the health care facility regarding organizational and operational aspects.

Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in primary care paediatricsGeneral objectives and their developmentBased on the document on the Priorities for the Improvement of PC Paediatrics,27 these are the general objectives (Table 2) of these programmes, and the necessary measures to achieve them (Table 3):

Improvements considered a priority in primary care paediatrics. Adapted from: Plan Nacional Resistencia Antibióticos. Objetivos de mejora prioritarios en Atención Primaria (Pediatría). Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS).27

| Prioritised improvement goals in primary care paediatrics |

|---|

| 1. Decrease overall antimicrobial prescribing |

2. Decrease prescribing for non-bacterial diseases:

|

3. Improve appropriateness of prescribing in specific diseases:

|

AOM, acute otitis media; APT, acute pharyngitis/tonsillitis; PC, primary care; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Measure to achieve the prioritised improvement goals in primary care paediatrics. Adapted from: Plan Nacional Resistencia Antibióticos. Objetivos de mejora prioritarios en Atención Primaria (Pediatría). Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS).27

| Measures required based on improvement goals |

|---|

| Reduction in overall antibiotic prescribing |

|

| Reduced prescription for non-bacterial diseases |

|

| Improve the appropriateness of prescribing in specific diseases |

|

AOM, acute otitis media; CDST, clinical decision support tool; EHRS, electronic health record system; PC, primary care; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Reduce the overall prescribing of antibiotics.

- 1)

Reduce prescribing in non-bacterial illnesses: upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), bronchiolitis, bronchitis, viral tonsillitis.

- 2)

Improve appropriate prescription in specific diseases, the use of narrow-spectrum antibiotics and the use of diagnostic tests for diseases for which they are available.

In addition, more specific objectives need to be established based on the particular circumstances of in each health care area, centre and professional, and should be revised periodically and redefined in successive stages. Strategies and interventions should also be planned to pursue these objectives, with particular emphasis on patient safety and quality of care.3

Measures required for implementationThe measures in ASPs must include and involve prescribers and every professional category of the centre, including professionals in training (undergraduate students, residents or interns in family medicine, paediatrics and nursing) to ensure that the activity and messages of every professional contribute to optimise antibiotic prescription and the education of the population on their appropriate use.3,20 For example, nurses and nurse assistants must know how to collect, store and transport samples correctly, and, in managing demand, must refrain from saying anything that would increase the expectations of patients and families regarding antibiotic prescription.

The appropriate measures and interventions may vary depending on the centre, even in facilities outside PC, and on the professional, but the participation of both is usually necessary for their implementation. The programme may involve multiple measures, implemented at different levels,3,20,25,28,29 and must be sustained through time.20,25

Measures related to health care organization- •

Prescribing empirical antibiotherapy appropriately requires consideration of the most frequent aetiologies and pathogens involved in each infectious disease and the corresponding prevalence of antimicrobial resistance. To this end, prescribers must have access to local, national and international epidemiological surveillance data, up to date and stratified by age, including the source of the samples (community-based, inpatient, emergency or hospital-based outpatient care). These data must be accessible at all times.

- •

A guideline on the indications of antibiotic treatment and prophylaxis in each infectious disease should be available for reference. It can be adapted to each care setting on the basis of epidemiological data. It also must include recommendations for patients in special situations.25

It is essential for this guideline to be included in the electronic health records system as an electronic clinical decision support tool25 to guide prescribing and address specific patient safety issues (kidney or liver failure, allergies, etc.), suggesting individualised alternatives based on the underlying disease of each patient.

- •

For diseases for which there are microbiological tests that can guide targeted antibiotherapy (rapid tests or other methods), guarantee access to these tests and to the indications for their use. Electronic health records systems must include specific features to record the use of diagnostic tests and their results.

- •

Guaranteeing electronic access in real time to laboratory, microbiological and imaging test results.

- •

Development of a system for providing guidance or answer questions through sessions focused on specific cases and empirical and/or targeted antibiotherapy to allow professionals to self-audit and individualised consultations.25

- •

Selective measures must be implemented to address areas in which inappropriate use is identified, for instance: revision of training courses, active recruitment of professionals in categories with poorer prescribing practices to deliver selective individualised guidance.

- •

Institutions must promote and involve PC professionals in projects aimed at determining patterns of drug resistance in the pathogens involved in the most common paediatric infectious diseases, in addition to facilitating the implementation of projects proposed by professionals. Sentinel surveillance studies must be planned with some regularity (every 1–2 years) using samples obtained in the community.

- •

The training of professionals is a core strategy in itself. It must be mandatory, that it, should be allotted time in the schedule of health care professionals, encouraged, and include contents previously found to be associated with a degree of improvement.

The contents must be adapted to the activity of different professionals, be based on real-world clinical practice and scenarios to illustrate the applicability of what is learned, and be maintained through time by keeping them available, taking advantage of technological resources and contemplating the development of mobile applications. In-person interventions geared to small groups or to individuals (individualised and face-to-face) seem to be most effective.3,20 It is important for educational interventions to be delivered by professionals in the same field that understand the actual circumstances of the care setting and the potential for action.30,31

In addition to covering the epidemiological and clinical aspects mentioned above, trainings should also address communication skills and techniques20 and the training of trainers.

Measures to be taken during prescription (Table 4)- •

The indications of antibiotherapy must be specified rigorously, always in relation to a diagnosis and including the correct dosage and duration of treatment.3,20 The prescriber must document the above in the health record (HR). The integration in the HER system of warning systems in the case of an inappropriate prescription with a reminder or link to the correct recommended prescribing practice (whether it is not to prescribe or prescribing a different drug) is extremely useful.3,25

- •

The patient must be informed about any decisions regarding antibiotherapy and correct adherence to treatment.3 Clinical decision support tools should be integrated in the EHR system.

Table 4.Sequential decision making and aspects to consider in antibiotic prescribing in primary care paediatrics.

Sequential decision making Considerations 1) Is antibiotherapy indicated?Is there a bacterial infection whose course will improve through the use of antibiotics?Is it a disease in which delayed antibiotic prescription would be applicable? Establish an accurate diagnosis of bacterial/viral infection to the extent possible: - •

Use of rapid diagnostic tests.

- •

Consider collection of a microbiological sample to confirm diagnosis and, in case of a positive result, perform antibiotic susceptibility testing

2) Which antibiotic? Patient characteristics to consider - •

Allergy (confirmed)

- •

Age

- •

Recurrence of disease and previous antibiotherapy

- •

Immunosuppression and other risk factors

- •

Based on the causative pathogen, type of infection, age and comorbidities of the patient

- •

Based on local antimicrobial resistance and susceptibility patterns for the pathogen.

- •

Select the effective antibiotic with the narrowest spectrum

- •

Use the effective antibiotic with the narrowest spectrum

3) At which dose? On which schedule? Dose that can achieve therapeutic concentrations of the antibiotic at the site of infection, considering:- Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of the drug- Site of infection- Patient characteristics.Determine dose according to current antimicrobial treatment guidelines and consensus documents. 4) For how long? The shortest necessary duration established by current antimicrobial treatment guidelines. 5) Does the patient or the family know the goals of antibiotherapy and the rules of adherence to the treatment? Patients must be informed about the indication and prescribing or lack thereof of antibiotherapy and correct adherence to treatment, as erratic administration can result in subtherapeutic doses and increase the risk of development of drug resistance. 6) Should treatment be modified based on microbiological test results or the course of the disease? Revise treatment: switch to appropriate spectrum, discontinue treatment or switch drugs if conclusive microbiological results are available. - •

These are essential to improve the knowledge about antibiotics of the population.32

- •

Promotion of preventive measures that contribute to reduce infection and, indirectly, antibiotic use: prevention of active and passive smoking, had hygiene,33 antisepsis, isolation and social distancing measures in ill individuals and vaccination.34

- •

Delivery of continuing education activities3,20 on the rational use of antibiotics in health care, education, social, sports and recreation centres, among other settings, through the collaboration of nursing staff, health education technicians, instructors of educational centres,35 paediatricians and pharmacy personnel,36 and with use of online resources, social networks, local mass media and learning aids (videos, infographics, etc.).20

- •

Participation in conferences devoted to the issue of antimicrobial drug resistance, specifically or in the framework of other health promotion activities (“health week”) in collaboration with local corporations and associations.

Indicators are useful to measure antibiotic consumption rates, antibiotic selection by group, the use of antibiotics not indicated for first-line treatment in most diseases (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, macrolides, third generation cephalosporins) or individual exposure to antibiotics. They are applicable to the Departments of Health of every autonomous community (AC) in Spain. They can also be used to assess the appropriateness of prescribing (qualitative indicators), although this depends to a large extent of adequate documentation in health records. The data must be broken down by age.37 Indicators can be calculated at the local, regional and national levels, and professionals should receive feedback on the information they provide regularly and frequently3,25 to be aware of current trends.

Indicators of antibiotic consumption in the paediatric population. Source: Plan Nacional Resistencia Antibióticos (PRAN). Indicadores de uso de antibióticos en Atención Primaria. Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS).37

| Definition | Formula | Improving trend | Standard | Stratification | Time interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of consumption of antibiotics for systemic use (J01), DTD in children under 15 years | DDD of ABX (J01) in children <15 yearsa 1000/no. health care cardsb (paediatric) x day | Decreased rate | Reference: national average | Total ≤14 years 0−4 years 5−9 years 10−14 years | Annual |

| Prevalence of ABX use or percentage of PED population that consumes ABX in 1 year (%) | No. patients (paediatric) who consumed ABX (J01)/ total number of health care cardsb (paediatric) x 100 | Reference: national average | Total ≤14 years 0−4 years 5−9 years 10−14 years | Annual | |

| Consumption of beta-lactamase-sensitive penicillins PED (%) | No. packages penicillin V + penicillin G (J01CE) (paediatric age group)/ no. packages of antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) x 100 | Increase in the proportion of beta-lactamase-sensitive penicillins | Reference: national average | Total ≤14 years 0−4 years 5−9 years 10−14 years | Annual |

| Consumption of amoxicillin relative to total consumption (%) | No. packages amoxicillin (paediatric age group)/ no. packages of antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) x 100 | Preferential use of amoxicillin in relation to broader-spectrum antibiotics | Reference: national average | Total ≤14 years0−4 years 5−9 years 10−14 years | Annual |

| Consumption of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid relative to total consumption (%) | No. packages amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (paediatric age group)/ no. packages of antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) x 100 | Decrease in the proportion of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | Reference: national average | Total ≤14 years 0−4 years 5−9 years 10−14 years | Annual |

| Relative consumption of amoxicillin compared to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (%) | No. packages amoxicillin (J01CA04) (paediatric age group) / no. packages amoxicillin (J01CA04) + no. packages amoxicillin -clavulanic acid (J01CR02) (paediatric age group) | Preferential use of amoxicillin in relation to combined therapy with amoxicillin- clavulanic acid | Reference: national average | Total ≤14 years 0−4 years 5−9 years 10−14 years | Annual |

| % consumption of macrolides over total consumption (%) | No. packages macrolides / no. packages antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) x 100 | Decrease in the proportion of macrolides | Reference: national average | Total ≤14 years 0−4 years 5−9 years 10−14 years | Annual |

| % consumption of 3rd generation cephalosporins over total consumption (%) | No. packages 3rd generation cephalosporins (J01DD) / no. packages antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) x 100 | Decrease in the relative use of third generation cephalosporins | Reference: national average | Total ≤14 years 0−4 years 5−9 years 10−14 years | Annual |

Since there are limitations to the “traditional” indicators (DDD, number of packages, etc.) for the measurement of prescribing in the paediatric age group, we propose assessing the validity of the “days of therapy” indicator (DOT: no. of days of treatment/1000 health cards of patients < 14 years per day) in primary care and, if confirmed, adding it to the battery of indicators. ABX, antibiotic/antibiotherapy; DDD, defined daily dose; PED, paediatrics.

Indicators may overestimate actual consumption in cases of delayed prescription.

It is important to attribute to each provider the actual prescriptions made by them, that is, to eliminate instances of induced prescription.

Monitoring and evaluation of interventions and measures- •

Antimicrobial stewardship programmes must include documentation and data retrieval systems to assess the introduction, implementation, outcomes and potential unintended deleterious effects of the applied interventions and measures.38 These systems must be available to health care professionals, and management and administrators of centres, health districts, health areas and departments of health.3,37

- •

Prescribers must record and document the indication, dose, schedule and duration of prescribed antibiotherapy.

- •

Institutions must promote and involve PC professionals in the development of projects to evaluate the outcomes of interventions implemented with the aim of improving prescribing, and facilitate the implementation of projects proposed by professionals.

- •

In agreement with other guidelines and documents focused on the field of paediatrics, we propose the days of therapy (DOT: days of treatment/1000 health care user cards) as a valid indicator.39

Some of the characteristics of PC (geographical dispersion, isolation, lack of time, large caseloads, etc.) are known barriers to the success of ASPs, as is the dependence on resources outside PC.

On the other hand, most infectious diseases managed at the PC level do not require microbiological testing, or these tests are not available for their diagnosis, which limits the availability of up-to-date information on their aetiology. This results in a high level of uncertainty in their management.

The units of measure used traditionally (DDD, number of packages, etc.) pose limitations in the measurement of prescription in the paediatric age group, given the variations in dosage based on age and/or weight, the large number of drugs prescribed in liquid dosage forms and the difficulty of prescribing different sizes of the same formulation in a single prescription.

ConclusionAntimicrobial stewardship programmes need to be implemented in PC paediatrics, adapted to the characteristics of these services and in coordination with other levels of care, as they have been found to play an important role in the reduction of bacterial drug resistance.

The availability of diagnostic resources must be improved, and software tools to guide prescribing need to be developed and integrated in PC electronic health records systems. Professionals must receive feedback on indicators and the outcomes of implemented interventions.

Professionals must be given time to perform interventions at the individual and community level, involving patients and the population in the rational use of antibiotics.

Scientific societies carry out important work to improve our practice; however, the continuing education of health care professionals and ASP team members should be the responsibility of administrative bodies, with no involvement from industry, mandatory, delivered during working hours and tied to established professional performance targets and evaluations.

FundingSpecific funding for the development of this document was not provided by any parties in the public, industry or non-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

The authors thank Dr Mamiko Onoda for her collaboration.