To prepare a list of highly toxic drugs in infants (HTDs) marketed in Spain, comparing those that reach the lethal dose in a child of 10 kg with the ingestion of one to three units.

MethodHTDs are defined as those capable of causing severe or lethal poisoning in children less than 8-year-old. Severe poisoning is considered as that corresponding to Grade 3 in the Poisoning Severity Score classification and to the “major effects” category in publications in the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC). A literature review was carried out on the annual reports of the AAPCC, as well as in PubMed, between January 2000 and February 2019 (key words: “severe”, “fatal”, “life-threatening”, “poisoning”, “child”, “paediatric”, “toxicological emergency”). An observational, retrospective study was also conducted on infants less than 8-year-old that were seen in a Paediatric Emergency Department due to suspected drug poisoning between July 2012 and June 2018.

The active ingredients responsible marketed in Spain were selected, and the lethal or highly toxic doses were determined. The number of units (pills) necessary to reach this dose in children of 10 kg was calculated.

ResultsA total of 7 HTD groups were identified: analgesics; psychotropics and other medication used in neurological disorders; catarrh decongestants – cough –antihistamine – asthma drugs; cardiovascular drugs; antibiotics, topical preparations, and other drugs. In 29 active ingredients, the ingestion of a single pill could cause death in 10 kg infant, in another 13, the ingestion of 2 pills could cause death, as well as the ingestion of 3 pills in 10 cases.

ConclusionThere are numerous HTDs marketed in Spain, some of which are available in potentially fatal presentations with few pills.

Elaborar un listado de medicamentos altamente tóxicos en la infancia (MAT), comercializados en España, diferenciando aquellos que alcanzan la dosis letal para un niño de 10 kg con la ingesta de una a tres unidades.

MétodoSe definió MAT como aquellos capaces de producir intoxicaciones graves o letales en niños menores de 8 años. Se consideró toxicidad grave la correspondiente al grado 3 en la clasificación Poisoning Severity Score y a la categoría “major effects” en las publicaciones de la American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC). Se realizó una revisión bibliográfica de los informes anuales de la AAPCC y de PubMed entre enero 2000 y febrero 2019 (palabras clave: “severe”, “fatal”, “life-threatening”, “poisoning”, “child”, “pediatric”, “toxicological emergency”). Además, se realizó un estudio observacional retrospectivo de menores de 8 años que consultaron en un servicio de urgencias pediátrico por sospecha de intoxicación farmacológica entre julio 2012 y junio 2018.

Se seleccionaron los principios activos responsables comercializados en España y se determinó la dosis letal o la dosis altamente tóxica. Se calculó el número de unidades necesarias para alcanzarla en niños de 10 kg.

ResultadosSe identificaron 7 grupos de MAT: analgésicos; psicofármacos y medicamentos neuromusculares; anticatarrales descongestivos-antitusígenos-antihistamínicos-antiasmáticos; medicamentos cardiovasculares; antimicrobianos; preparados tópicos y otros medicamentos. En 29 principios activos, la ingesta de una única unidad podría causar la muerte en un lactante de 10 kg de peso, en 13 podría causarla la ingesta de dos unidades y en 10 la ingesta de tres unidades.

ConclusiónExisten numerosos MAT comercializados en España, algunos de ellos disponibles en presentaciones potencialmente letales con pocas unidades.

Medicines are the substances involved most frequently in paediatric poisoning cases. According to the Working Group on Poisonings of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría (Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Medicine) (GTI-SEUP), 59.2% of children aged less than 7 years that seek care in paediatric emergency departments (PEDs) for suspected poisoning do so following exposure to a medicinal drug.1

Since its launch in 2008, the Toxicology Observatory of the GTI-SEUP has not registered any fatal drug poisoning cases in children.2 However, there are descriptions of fatal cases in the international literature, among which we would like to highlight the annual reports of the National Poison Data System (NPDS) of the American Association of Poison Control Centers and studies on paediatric deaths resulting from exposure to toxic substances.3,4 Some of these deaths followed ingestion of very small amounts of the drug (1 or 2 tablets or sips).5–9 These events have led to the coining of the term one-pill killer or the phrase one pill can kill, which refers to drugs the ingestion of a single tablet or teaspoonful of which is enough to reach a lethal dose (LD) to a child with a body weight of 10 kg.10,11

The increased life expectancy and broader therapeutic armamentarium currently available for treatment of chronic diseases entail that a considerable portion of the population consumes medicines habitually. While the pharmaceutical industry has integrated the use of child-resistant packaging, drugs manufactured for the adult population, which have a higher concentration of the active ingredient per unit, may be dangerous to the youngest individuals. The risk is even greater if drugs are stored anywhere other than their original packaging,12 in pill boxes or in novel custom pill dispensing systems, which are very appealing due to their modern design and lack childproof safety mechanisms.

There have been life-threatening and even fatal cases of poisoning following ingestion of various products and drugs sold over the counter, such as ointments containing camphor13,14 or methyl salicylate.9,15 Families do not perceive these products as actual drugs and use even fewer precautions. Thus, we have a long way to go on the prevention of unintentional drug poisonings in the paediatric population.

The aims of our study were:

- 1

To craft a list of drugs highly toxic to children (DHTCs) currently marketed in Spain.

- 2

To craft a list of drugs currently marketed in Spain that can reach a LD to a child with a body weight of 10 kg with the ingestion of 1 to 3 units.

- -

DHTC: drug that can cause severe or fatal poisoning in children aged less than 8 years. We defined severe poisoning as poisoning that is life-threatening or causes permanent sequelae. It corresponds to grade 3 in the Poisoning Severity Score (PSS), a classification developed and validated by the European Association of Poison Centres and Clinical Toxicologists,16 and the major effects category applied in the publications of the American Association of Poison Control Centers.

- -

One-pill killer or drug that can be fatal with ingestion of a few units: drug that could cause the death of an infant with a body weight of 10 kg with ingestion of 1–3 units. In the case of solid dosage forms, we defined unit as a single tablet, capsule, patch, etc. For liquid or semisolid dosage forms, we defined unit as a volume of 5 mL or a weight of 5 g.

We performed a systematic review of the literature. In addition, we conducted a retrospective observational study of patients managed for suspected poisoning in a PED.

Literature reviewThe literature review consisted of 2 parts:

- 1

Review of the annual reports of the NPDS of the American Association of Poison Control Centers from 2000 to 2017. We selected cases of fatal poisoning following ingestion of a single drug in children aged less than 8 years, provided that it was certain or highly probable that ingestion of the drug had been the cause of death.

- 2

Review of articles indexed in the PubMed database published from January 2000 to February 2019, using the following keywords in the search: severe, fatal, life-threatening, poisoning, child, paediatric and toxicological emergency. Three of the authors with experience in reviewing the medical literature conducted this review. Out of all the results of the search, the reviewers selected articles published in English, French or Spanish on the subject of paediatric drug poisoning. The reviewers carefully read the full text of the selected articles to identify those that included cases of severe or fatal poisoning following ingestion of a single drug in children aged less than 8 years, and excluded annual reports of the NPDS of the American Association of Poison Control Centers and systematic reviews on the subject that did not include the necessary information to apply the selection criteria of our study.

We conducted a retrospective observational study that included patients aged less than 8 years that visited the PED with suspected drug poisoning between January 2012 and June 2018. We reviewed the data corresponding to the emergency visit in the electronic health record of these patients and selected cases of severe or fatal poisoning following ingestion of a single drug.

The PED where we conducted the study corresponds to an urban tertiary care women’s and children’s hospital that manages approximately 100 000 paediatric visits per year. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the hospital.

After identifying the DHTC involved in each case, we verified that the drug was marketed in Spain by consulting the online medicines information centre of the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices, AEMPS).

Identification of drugs that could be lethal with ingestion of a few unitsTo determine the dose that could be lethal for children for each of the DHTCs, we consulted the reviewed literature, the POISINDEX and TOXBASE databases and the NPDS annual reports published by the American Association of Poison Control Centers. The LD is defined as the minimum ingested dose (amount ingested per kg of body weight) known to have caused death in children, if case reports included sufficient data to make the calculation: units and dose of the drug ingested, age and/or weight of the child. In the absence of this information, we extrapolated the LD (extrapolated lethal dose [ELD]) from the minimum ingested dose known to have caused death in adults (amount ingested per kg of body weight) recorded in POISINDEX or TOXBASE or based on notified cases, assuming a mean weight of 75 kg for men and 60 kg for women.

When it came to DHTCs that caused deaths but for which data were not available that allowed calculation of the LD in children or adults, or DHTCs associated with severe poisoning cases but no lethal cases reported in the literature (PSS grade 3), we calculated the dose that caused severe toxicity, or highly toxic dose (HTD). The HTD corresponds to the minimum ingested amount (amount by kg of body weight) known to have caused severe poisoning in children.

Last of all, we calculated the number of units (of the most concentrated dosage form available in Spain) needed to reach the LD, ELD or HTD in children with a body weight of 10 kg, and classified drugs in which this dose was reached with 1–3 units as one-pill killers or “drugs that may be lethal with the ingestion of a few units”.

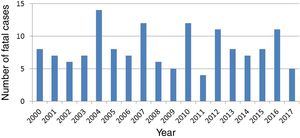

ResultsLiterature reviewThe review of the NPDS annual reports of the American Association of Poison Control Centers published since 2000 yielded 146 lethal poisoning cases in children aged less than 8 years following ingestion of a single drug that was unquestionably or very likely the cause of death. The drugs involved most frequently were opiates (68 cases; 46.6%), followed by antihistamines, either as single-entity drug products or as part of a multi-ingredient cold medicine (19 cases; 13%). Table 1 lists all the active ingredients involved in these cases. Fig. 1 shows the temporal trends in the number of lethal cases per year.

Drugs involved in fatal poisoning cases in children aged less than 8 years documented in the NPDS annual reports of the American Association of Poison Control Centers for the 2000-2017 period (N = 146 cases).a.

| Drug group and active ingredient | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Analgesics | 83 (56.8%) |

| Opiates | 68 (46.6%) |

| Methadone | 35 (24%) |

| Oxycodone | 15 (10.3%) |

| Morphine | 10 (6.8%) |

| Buprenorphine | 5 (3.4%) |

| Fentanyl | 2 (1.4%) |

| Hydromorphone | 1 (0.7%) |

| Non-narcotic analgesics | 15 (10.3%) |

| Paracetamol | 9 (6.2%) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 6 (4.1%) |

| Antihistamines, cough and cold medication, asthma medication | 23 (15.8%) |

| Diphenhydramine | 13 (8.9%) |

| Chlorphenamine + hydrocodoneb | 3 (2%) |

| Benzonatate | 3 (2%) |

| Dextromethorphan | 1 (0.7%) |

| Diphenhydramine + brompheniramineb | 1 (0.7%) |

| Promethazine | 1 (0.7%) |

| Doxylamine | 1 (0.7%) |

| Cardiovascular drugs | 15 (10.3%) |

| Flecainide | 5 (3.4%) |

| Nifedipine | 4 (2.7%) |

| Diltiazem | 2 (1.4%) |

| Clonidine | 2 (1.4%) |

| Digoxin | 1 (0.7%) |

| Propafenone | 1 (0.7%) |

| Psychotropic drugs and other medication used in neurological disorders | 14 (9.6%) |

| Antidepressants | 11 (7.5%) |

| Bupropion | 5 (3.4%) |

| Amitriptyline | 3 (2%) |

| Desipramine | 1 (0.7%) |

| Imipramine | 1 (0.7%) |

| Sertraline | 1 (0.7%) |

| Antipsychotics and antiepileptics | 3 (2%) |

| Chlorpromazine | 1 (0.7%) |

| Haloperidol | 1 (0.7%) |

| Carbamazepine | 1 (0.7%) |

| Antimicrobials | 3 (2.0%) |

| Isoniazid | 2 (1.4%) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (0.7%) |

| Topical medication | 2 (1.4%) |

| Lidocaine 2% | 2 (1.4%) |

| Other | 6 (4.1%) |

| Atropine-diphenoxylate | 2 (1.4%) |

| Colchicine | 1 (0.7%) |

| Chloral hydrate | 1 (0.7%) |

| Iron | 1 (0.7%) |

| Metformin | 1 (0.7%) |

The literature search in PubMed yielded 109 articles that included cases of severe or lethal poisoning following ingestion of a single drug in children aged less than 8 years. Of these articles, 73 corresponded to case reports or case series, 13 to literature reviews that included specific data on cases, 21 to retrospective observational studies and 2 to prospective observational studies. Opiates were the type of drug discussed in the highest number of publications (n = 24), followed by cardiovascular agents (n = 15) and antidepressants (n = 14). Table 2 lists the active ingredients involved in the cases reported in these articles.

Drugs involved in fatal poisoning cases in children aged less than 8 years identified in articles indexed in PubMed.a.

| Drug group and active ingredient (number of articles that reported cases) |

|---|

| Psychotropic drugs and medication used in neuromuscular disorders (28) |

| Antidepressants (14) |

| Amitriptylineb |

| Bupropion |

| Citalopram |

| Desipramineb |

| Escitalopram |

| Imipramineb |

| Fluoxetine |

| Paroxetine |

| Sertralineb |

| Vilazodone |

| Antipsychotics (5) |

| Chlorpromazine b |

| Clozapine |

| Haloperidol |

| Olanzapine |

| Risperidone |

| Thioridazine b |

| Ziprasidone |

| Antiepileptics (5) |

| Carbamazepine |

| Lamotrigine |

| Sodium valproate |

| Other psychotropic drugs and medication used in neurological disorders(4) |

| Baclofen |

| Fampridine |

| Rivastigmine |

| Tolperisone |

| Analgesics (27) |

| Opiates (24) |

| Buprenorphine-naloxone |

| Codeineb |

| Fentanylb |

| Hydrocodoneb |

| Hydromorphoneb |

| Methadoneb |

| Morphineb |

| Oxycodoneb |

| Propoxypheneb |

| Tapentadol |

| Tramadol |

| Non-opioid analgesics (3) |

| Paracetamolb |

| Acetylsalicylic acidb |

| Topical medication (15) |

| Camphorb |

| Topical anaesthetics (benzocaine; dibucaine; lidocaineb) |

| Apraclonidine |

| Benzydamine |

| Imidazolines |

| Methyl salicylateb |

| Podophyllotoxin |

| Cardiovascular drugs (15) |

| Amlodipine |

| Clonidineb |

| Digoxinb |

| Diltiazem |

| Flecainide |

| Isradipine |

| Nifedipineb |

| Propafenone |

| Propranolol |

| Verapamil |

| Antimicrobials (6) |

| Chloroquineb |

| Dapsone |

| Isoniazid |

| Quinineby quinidineb |

| Antihistamines and cold, cough and asthma medication (6) |

| Benzonatateb |

| Diphenhydramineb |

| Dextromethorphanb |

| Ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, phenylpropanolamineb |

| Promethazineb |

| Theophylline |

| Other drugs (16) |

| Gout medication (6) |

| Colchicineb |

| Sulfonylureas (4) |

| Glibenclamide |

| Glipizideb |

| Metformin |

| Other (6) |

| Diphenoxylate-atropineb |

| Chloral hydrateb |

| Iron |

| Potassiumb |

We included articles that reported fatal cases and/or severe cases (PSS grade 3) of poisoning following ingestion of a single drug in children aged less than 8 years published between January 2000 and February 2019 indexed in PubMed. We excluded the NPDS annual reports published by the American Association of Poison Control Centers. Some articles reported cases of poisoning involving different drug classes.

Out of all the active ingredients involved in fatal or severe poisonings in children aged less than 8 years found in the literature review (NPDS annual reports and PubMed), we excluded 9 because they were not marketed in Spain: benzonatate, desipramine, diphenoxylate-atropine, hydrocodone, isradipine, propoxyphene, thioridazine, tolperisone and vilazodone.

Observational studyIn the period under study, 579 patients aged less than 8 years visited the PED due to suspected drug poisoning, who amounted to 0.09% of the 609 690 patients managed in that time frame. Two of these patients had severe poisoning after ingestion of a single drug (clomethiazole in one and dextromethorphan in the other). Both cases occurred in 2016. Table 3 presents the main characteristics of these cases.

Cases of severe poisoning (PSS grade 3) in children aged less than 8 years following ingestion of a single drug or health product managed in a single paediatric emergency department.

| Age | Sex | Weight | Active ingredient (drug group) | Ingested amount | Setting of exposure | Symptoms | Management | Sequelae after discharge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 months | F | 9,5 kg | Clomethiazole capsules 192 mg(psychotropic drug) | Open package, amount unknown | Relative’s home | Cardiac arrest on arrival of EMT | Basic CPR with good response. ETI and respiratory support. | No |

| 2 years | M | 15 kg | Dextromethorphan Oral drops 15 mg/mL(antitussive) | Maximum of 15 mg/kg | Home | Decreased consciousness and hypoventilation | Oxygen therapy. Naloxone in CI | No |

CI, continuous infusion; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMT, emergency medical team; ETI, endotracheal intubation; F, female; M, male; PED, paediatric emergency department.

The review of the cases managed at this single PED allowed us to add clomethiazole to the list of DHTCs, as it had not been identified as such through the literature review.

Drugs highly toxic and potentially lethal with the ingestion of a few units marketed in SpainTable 4 lists the DHTCs marketed in Spain. They could be classified into 7 large groups: analgesics; psychotropic drugs and other medication used in neurological disorders; antihistamines and cold, cough and asthma medication; antimicrobials; topical medication; other drugs.

Drugs highly toxic in children available in Spain.

| Analgesics |

|---|

| Acetylsalicylic acid |

| Opiates |

| Paracetamol |

| Antihistamines and cold, cough and asthma medication |

| Antitussive opiates: codeine and dextromethorphan |

| Antihistamines |

| Sympathomimetic decongestants |

| Imidazoline decongestants |

| Theophylline |

| Antimicrobials |

| Antimalarials: chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinine |

| Dapsone |

| Isoniazid |

| Cardiovascular drugs |

| Calcium channel blockers |

| Beta blockers |

| Clonidine |

| Digoxin |

| Flecainide |

| Propafenone |

| Psychotropic drugs and other medication used in neurological disorders |

| Antidepressants |

| Antiepileptics: carbamazepine, lamotrigine and valproic acid |

| Typical and atypical antipsychotics |

| Baclofen |

| Clomethiazole |

| Fampridine |

| Rivastigmine |

| Topical medication |

| Local anaesthetics: benzocaine, dibucaine and lidocaine |

| Camphor |

| Apraclonidine |

| Benzydamine |

| Methyl salicylate |

| Podophyllotoxin |

| Other drugs |

| Colchicine |

| Chloral hydrate |

| Iron |

| Potassium |

| Sulfonylureas: glibenclamide, glipizide and metformin |

We calculated the LD for 66 active ingredients (Table 5). We found sufficient information in the literature and the consulted databases to estimate the paediatric LD for 30 of these active ingredients. For the remaining ingredients, we calculated the ELD or HLD. We found that 78.8% (52/66) of the identified active ingredients met the criteria to be considered one-pill killers or drugs that may be lethal with the ingestion of a few units. We found that for 29 of these active ingredients, ingestion of a single unit could be lethal to an infant with a body weight of 10 kg, for 13 ingredients, ingestion of 2 units could be lethal, and for 10 ingredients, ingestion of 3 units could be lethal. These active ingredients corresponded to the following types of drugs: cardiac dysrhythmia medications, asthma medications, antidiabetics, antihypertensives, antipsychotics, opiates and topical drugs (analgesics, anaesthetics and decongestants).

Potentially lethal doses of drugs highly toxic to children available in Spain and number of units required to reach a potentially lethal dose in an infant with a body weight of 10 kg.

| Drug class | Active ingredient | Minimum lethal dose (LD) (mg/kg) | Minimum extrapolated lethal dose (ELD) (mg/kg) | Highly toxic dose (HTD) (mg/kg) | LD/HTD for a child ≤ 10 kg (mg) | Dosage forms delivering the highest dose (mg) marketed in Spain | Number of unitsb delivering potential LD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics | |||||||

| Opiates | Buprenorphine-naloxonea | 0.4 | 4 | Oral tablets 8 mg | 1 | ||

| Fentanyla | 0.42 | 4.2 | Patch 100 µg/h (23.12 mg) | 1 | |||

| Hydromorphonea | 0.3 | 3 | Extended-release tablets 32 mg | 1 | |||

| Methadonea | 0.5−1 | 10 | Tablets 40 mgOral solution 5 mg/mL, 20 mL bottle (5 mL =25 mg) | 1 | |||

| Morphinea | 12 | 120 | Extended-release tablets 200 mg | 1 | |||

| Oxycodonea | 1.2 | 12 | Extended-release tablets 80 mgOral solution 10 mg/mL, 30 mL bottle (5 mL =50 mg) | 1 | |||

| Tapentadol | ND | 10 | 100 | Extended-release tablets 250 mg | 1 | ||

| Tramadola | ND | 38 | 380 | Extended-release tablets 400 mgOral drops 100 mg/mL, 30 mL bottle (5 mL =500 mg) | 1 | ||

| Antihistamines and cold, cough and asthma medication | |||||||

| Asthma medication | Theophyllinea | ND | 8.4 | 84 | Extended-release tablets 300 mg | 1 | |

| Antihistamines | Promethazine a | 17 | 170 | 2% cream (20 mg/g), 60 g tube (5 g =100 mg) | 2 | ||

| Antitussives | Diphenhydraminea | 12 | 120 | Tablets 50 mg | 3 | ||

| Codeinea | 4 | 40 | Tablets 30 mg | 2 | |||

| Dextromethorphan | ND | 38 | 380 | Syrup 15 mg/5 mL, 200 mL bottle (5 mL =15 mg) | 25 (126 mL) | ||

| Antimicrobials | |||||||

| Chloroquinea | 27 | 270 | Tablets 155 mg | 2 | |||

| Dapsone | ND | 16 | 10 | 160 | Tablets 100 mg (ID) | 2 | |

| Hydroxychloroquinea | ND | 20 | 200 | Tablets 200 mg | 1 | ||

| Isoniazida | ND | 80 | 800 | Tablets 300 mg | 3 | ||

| Quinine | ND | 60 | 600 | Capsules 325 mg (CP) | 2 | ||

| Quinidine | 300 | 3000 | Extended-release capsules 300 mg | 10 | |||

| Cardiovascular drugs | |||||||

| Antiarrhythmics | Flecainidea | 7.8 | 78 | Tablets 100 mg | 1 | ||

| Propafenone | ND | 15 | 150 | Tablets 300 mg | 1 | ||

| Antihypertensives | Clonidine | ND | 0.01 | 0.1 | Tablets 0.15 mg | 1 | |

| Propranolola | ND | 29 | 290 | Tablets 40 mg | 8 | ||

| Sotalol | ND | 45 | 450 | Tablets 80 mg | 6 | ||

| Amlodipine | ND | 1 | 0.3 | 10 | Tablets 10 mg | 1 | |

| Diltiazema | 15 | 150 | Extended-release tablets 300 mg | 1 | |||

| Nifedipinea | 15 | 150 | Capsules 60 mg | 3 | |||

| Verapamila | 15 | 150 | Extended-release tablets 240 mg | 1 | |||

| Digitalis glycosides | Digoxina | 0.4 | 4 | Tablets 0.25 mgOral solution 0.05 mg/mL, 60 mL bottle (5 mL =0.25 mg) | 16 | ||

| Psychotropic drugs and other medication used in neurological disorders | |||||||

| Anticholinesterases | Rivastigmine | ND | 0.6 | 6 | Tablets 6 mgOral solution 2 mg/mL, 120 mL bottle (5 mL =10 mg)Patch 13.3 mg | 1 | |

| Antidepressants | Bupropion | ND | 70 | 48 | 700 | Tablets 300 mg | 3 |

| Citalopram | ND | 10 | 100 | Tablets 30 mg | 4 | ||

| Sertralinea | 13 | 130 | Tablets 100 mgOral solution 20 mg/mL, 60 mL bottle (5 mL =100 mg) | 2 | |||

| Amitriptylinea | 15 | 150 | Tablets 75 mg | 2 | |||

| Imipraminea | 15 | 150 | Tablets 50 mg | 3 | |||

| Antipsychotics and other psycholeptic drugs | Clomethiazole | ND | 143 | 1430 | Tablets 192 mg | 8 | |

| Chlorpromazinea | 20 | 200 | Oral solution 40 mg/mL, 30 mL bottle (5 mL =200 mg) | 1 | |||

| Clozapinea | ND | 35 | 350 | Tablets 200 mg | 2 | ||

| Doxylaminea | 1 | 10 | Tablets 25 mg | 1 | |||

| Haloperidol | ND | 1.5 | 15 | Oral solution 20 mg/mL, 30 mL bottle (5 mL =100 mg) | 1 | ||

| Olanzapine | ND | 4.2 | 42 | Tablets 20 mg | 3 | ||

| Risperidone | ND | 0.2 | 2 | Tablets 6 mgOral suspension 1 mg/mL, 100 mL bottle (5 mL =5 mg) | 1 | ||

| Ziprasidone | ND | 3 | 30 | Tablets 80 mg | 1 | ||

| Antiepileptics | Valproic acid | ND | 750 | 7500 | Oral solution 200 mg/mL, 40 mL bottle (5 mL =1000 mg) | 8 | |

| Carbamazepinea | 100 | 1000 | Tablets 400 mg | 3 | |||

| Lamotrigine | ND | 53 | 80 | 530 | Tablets 200 mg | 3 | |

| Muscle relaxants | Baclofen | ND | 15 | 12.5 | 150 | Tablets 25 mg | 6 |

| Other CNS drugs | Fampridine | ND | 2.3 | 23 | Extended-release tablets 10 mg | 3 | |

| Other drugs | |||||||

| Antidiabetics | Glibenclamidea | 0.1 | 1 | Tablets 5 mg | 1 | ||

| Glipizide a | 0.1 | 1 | Tablets 5 mg | 1 | |||

| Metformin | ND | 550 | 5550 | Tablets 1000 mg | 6 | ||

| Gout medication | Colchicinea | 0.5 | 5 | Tablets 1 mg | 5 | ||

| Sedatives and hypnotics | Chloral hydratea | 70 | 700 | Oral solution 100 mg/mL, 50 mL bottle (CP) (5 mL =500 mg) | 2 | ||

| Mineral and ion supplements | Irona | ND | 60 | 600 | Tablets 105 mg elemental iron (325 mg Fe2+) | 6 | |

| Potassium a | 190 | 1900 | Extended-release tablets (1080 mg potassium citrate =390 mg elemental potassium) | 5 | |||

| Topical medication | |||||||

| Analgesics | Benzydamine | 70 | 700 | Granules 500 mg Vaginal solution | 2 | ||

| Methyl salicylatea | 490 (0.5 mL) | 4900 | Gaultheria oil (methyl salicylate 98%), 30 mL bottle (5 mL =4900 mg) | 1 | |||

| Local anaesthetics | Benzocaine | ND | 10 | 100 | Haemorrhoid cream 60 mg/g, 50 g tube (5 g =300 mg)Oral aerosol 50 mg/mL in 5 mL solution (5 mL =2500 mg) | 1 | |

| Cinchocaine = dibucaine | ND | 12.5 | 125 | Rectal cream 5 mg/g, 30 g tube (5 g =25 mg) | 5 | ||

| Lidocainea | ND | 50 | 500(25 mL of 2% solution) | Patch 5% (700 mg lidocaine)Oral aerosol 150 mg/mL, 60 mL solution (5 mL =750 mg) | 1 | ||

| Cytotoxic drugs | Podophyllotoxin | ND | 250 | 2500 | Topical solution 25%, 10 mL bottle (CP) (5 mL =1250 mg) | 2 | |

| Imidazolines | Apraclonidine | ND | 2.5 | 25 | Eye drops 5 mg/mL, 5 mL bottle (5 mL =25 mg) | 1 | |

| Naphazoline | ND | 0.4 | 4 | Nasal drops 0.05%, 35 mL bottle (5 mL =2.5 mg)Eye drops 0.5 mg/mL, 10 mL bottle (5 mL =2.5 mg) | 2 | ||

| Oxymetazoline | ND | 0.8 | 8 | Nasal drops 0.5 mg/mL, 10 mL bottle (5 mL =2.5 mg) | 3 | ||

| Xylometazoline | ND | 0.4 | 4 | Nasal drops 0.5 mg/mL, 10 mL bottle (5 mL =2.5 mg) | 2 | ||

| Rubefacients | Camphora | 30 | 300 | Cutaneous solution 10 g, 100 mL bottle (5 mL =500 mg)Nasal stick 396.7 mg | 1 | ||

CNS, central nervous system; CP, compounded preparation; ID, imported drug available in Spain; ND, no data available in the reviewed literature.

Many DHTCs are currently marketed in Spain. Furthermore, many of these drugs belong to the drug groups involved most frequently in cases of suspected unintentional drug poisoning managed in PEDs in Spain. Thus, based on data published by the GTI-SEUP, psychotropic drugs account for 24.5% of visits due to inadvertent drug exposure, cold medicines for 16.2% and analgesics for 15.4%.17

The review of the NPDS annual reports published by the American Association of Poison Control Centers showed that in the United States, the drugs involved most frequently in fatal drug poisonings in children aged less than 8 years are opiates and antihistamines. In the United Kingdom, Anderson et al3 reviewed the data collected by the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) from 2008 to 2014 and mortality data published by the Office for National Statistics for the 2001–2013 period. The authors identified 28 fatal cases in children aged less than 5 years, of which 16 (57%) resulted from exposure to methadone. Iron also was frequently involved, as it caused 1 death and 13 of the 69 severe cases (PSS grade 3).

In Australia, Pilgrim et al. reviewed data for the 2003–2013 period collected by the National Coronial Information System and found 19 fatal cases of acute drug poisoning in children aged less than 16 years. Prescription opiates were responsible for 10 cases and prescription psychotropic drugs for 6.4

In Spain, reports on mortality trends document 30 cases of fatal unintentional poisoning following exposure to toxic substances in children aged up to 14 years between 2008 and 2016 (12 cases in children aged less than 5 years), although the reports did not specify the drugs involved.18 We ought to highlight that the Toxicology Observatory of the GTI-SEUP did not report any fatal cases. A possible explanation is that the observatory only documents poisoning cases managed at participating PEDs on the 13th, 14th and 15th of each month.

Some of the deaths caused by opiates documented in the NPDS annual reports of the American Association of Poison Control Centers followed ingestion of a single methadone,5,6 buprenorphine-naloxone7 or oxicodon8 tablet. One of the salient reported cases of death due to inappropriate use of a drug corresponds to the administration of a 30 mg oxycodone tablet to a boy aged 7 years with a body weight of 48 kg that had toothache that did not respond to ibuprofen.8 There have also been fatal cases in obese children that were given a prescription for codeine for treatment of postoperative pain or as a cough suppressant.19 Two girls aged 1 and 4 years died after ingesting a used transdermal fentanyl patch.20,21

In Spain, all the opiates in the market reached a LD for children with a weight of 10 kg with a single unit, with the exception of codeine, which would reach a LD with two 30 mg tablets.

In the reviewed literature, psychoactive drugs and other nervous system and musculoskeletal system drugs were the types of drugs involved most frequently in severe or fatal drug poisoning cases. They also accounted for 9.5% of the deaths documented in the NPDS annual reports of the American Association of Poison Control Centers. Most of these deaths occurred in infancy and early childhood and presented with convulsive seizures and cardiovascular toxicity following accidental ingestion of bupropion or amitriptyline tablets.20,22–24 Three of the cases were homicides, as the caregivers had intentionally administered sertraline or amitriptyline to sedate the child.25,26 Some highly toxic psychotropic drugs and other nervous system and musculoskeletal system drugs are used almost exclusively in adults and paediatricians are not familiar with them. This is the case of rivastigmine or clomethiazole, used for management of Alzheimer disease or dementia. A case has been reported of respiratory failure in the context of cholinergic syndrome in a child aged 3 years that ingested 1 or 2 tablets of rivastigmine.27 Although we did not find any references to clomethiazole in our literature review, 1 of the patients managed at the PED in the retrospective study had severe poisoning and experienced cardiac arrest following ingestion of an unknown number of clomethiazole capsules.

Drugs for symptomatic treatment of the common cold are widely used in the paediatric population despite the lack of scientific evidence in support of this practice, and they are one of the groups of drugs involved most frequently in unintentional poisonings.17 An extensive review of reported fatalities by Dart et al. identified 99 deaths in children aged less than 6 years that were probably related to cough and cold medications, and the most frequently involved drugs were pseudoephedrine, diphenhydramine and dextromethorphan.28 This study found that in most cases the drug was administered by an adult, either with therapeutic intent or in an instance of child abuse. Another aspect worth highlighting is the involvement of products combining several active ingredients with a high toxicity.8,25,29 Dextromethorphan was the agent involved in one of the severe paediatric poisoning cases managed in the PED under study.

Despite the generalised perception that topical dosage forms are harmless, some of them are among the drugs that can be highly toxic to children. This is the case of local anaesthetics such as lidocaine, dibucaine and benzocaine. There have been cases of severe neurotoxicity and deaths associated with the misuse of lidocaine viscous (recurrent administration of doses higher than prescribed to alleviate symptoms of tooth eruption) or ingestion of a single unit of product.30 Dibucaine, marketed in Spain as an ingredient in a haemorrhoid cream, has a high cardiotoxicity.30,31 There are several reports in the literature of severe methaemoglobinaemia following ingestion of topical anaesthetics containing benzocaine.30

Other topical medications that may cause severe toxicity in children aged less than 8 years are products containing camphor or methyl salicylate,13–15 imidazolines,32 apraclonidine,33 benzydamine34 or podophyllotoxin.35

Antiarrhythmics and some antihypertensives (calcium channel blockers, beta blockers and clonidine) can not only cause severe and fatal poisoning in children, but also do so with very small amounts of the drug.32,36,37 In Spain, there are several dosage forms of flecainide, propafenone, clonidine, amlodipine, diltiazem and verapamil in the market that can reach a LD to children with a body weight of 10 kg in a single tablet and thus can be considered one-pill killers.

Due to their ubiquity in homes, we also ought to highlight sulphonylureas, which may cause severe hypoglycaemia leading to convulsive seizures and coma,23,38 and also iron.3,39

There are limitations to our study. Due to the study design, which was based on a literature review, there may have been cases in the period under study that were not reported to the consulted sources or that would not be identified through the key words used in the search. Thus, we may have underestimated the toxicity of some drugs. In some cases, a lack of data (both in the reviewed clinical cases and the cases included in the TOXBASE and POISINDEX databases) made it impossible to calculate the LD. Extrapolating data from the adult population can yield inaccurate results due to pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic differences between age groups.

In conclusion, our study showed that drugs highly toxic to children are currently marketed in Spain, some of which are available in dosage forms that can be lethal with ingestion of only a few units. To reduce risk, this information must be disseminated among the health professionals that prescribe and dispense these drugs and those that manage patients exposed to these substances. A strategy that may prove particularly effective would be to implement interventions in the pharmacy setting to educate families at the time of dispensation of DHTCs. In recognition of the importance of health education, educational audiovisual contents have been developed at the regional level with the support of the government to be played in the waiting rooms of health care facilities.40

On the other hand, it would be very useful to establish a national register of severe or fatal cases of unintentional drug poisoning. A close collaboration of this register and the AEMPS would facilitate the generation of alerts, raising awareness on the use of specific drugs and other health products, and the dissemination of safety measures.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Sánchez L, Aguilar-Salmerón R, Pi-Sala N, Gispert-Ametller MÀ, García-Peláez M, Broto-Sumalla A et al. Disponibilidad en España de “one pill killers” y otros medicamentos altamente tóxicos en la infancia. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;93:380–395.

Previous presentations: this study was presented at the 24th Meeting of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría,April 2019, Murcia, Spain; and the XXII National Conference of Clinical Toxicology (Jornadas Nacionales de Toxicología Clínica), October 2018, Cordoba, Spain, receiving the award to the best communication in research in clinical toxicology in the latter.