The mumps virus (MuV), or Myxovirus parotiditis, continues to cause sporadic cases and outbreaks of disease. This is associated to the progressive waning of immunity against the mumps component of the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine in absence of a natural booster (especially from 10 years after administration of the second dose), the use in the 1993–1999 period of a vaccine that had the Rubini strain, which proved to be less effective, and the presence of pockets of unvaccinated people in the population.1 In Spain, 10 260 cases were notified in 2017 and 8996 in 2018, a significant increase compared to previous seasons.2

Some of the infectious agents other than MuV that may be involved in parotitis as a general clinical presentation include influenza A virus, parainfluenza virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), adenovirus, coxsackievirus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), parvovirus B19, herpesvirus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, as well as gram-positive bacteria, atypical mycobacteria and Bartonella species.3–5 In the paediatric population, these pathogens are probably more frequent causative agents compared to MuV. This, combined with the benign course of most presentations, leads many paediatric health care facilities to make the diagnosis without an aetiological investigation. The aim of our study was to establish the viruses involved in cases of parotitis in our area.

We carried out a retrospective study through the collection of data corresponding to 2 full years (2016 and 2017), including all patients given a diagnosis of parotitis (with swelling of the parotid glands being a requirement for inclusion) in the paediatric emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in Barcelona that manages patients up to age 16 years and based on diagnostic judgment of the paediatrician in charge of the patient. Per hospital protocol, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for detection of MuV in saliva and urine samples were performed in patients with parotitis. Serologic tests were added if blood tests were requested by the paediatrician in charge based on his or her clinical judgment. When it came to serologic testing, in case of negative results of the test for detection of MuV in saliva, molecular methods were used for detection of influenza A and B virus, respiratory syncytial virus A/B, adenovirus, metapneumovirus, coronavirus nl63/OC43/229E, enterovirus, rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus, EBV and CMV. Mump viruses were characterised by partial sequencing of the small hydrophobic (SH) gene.

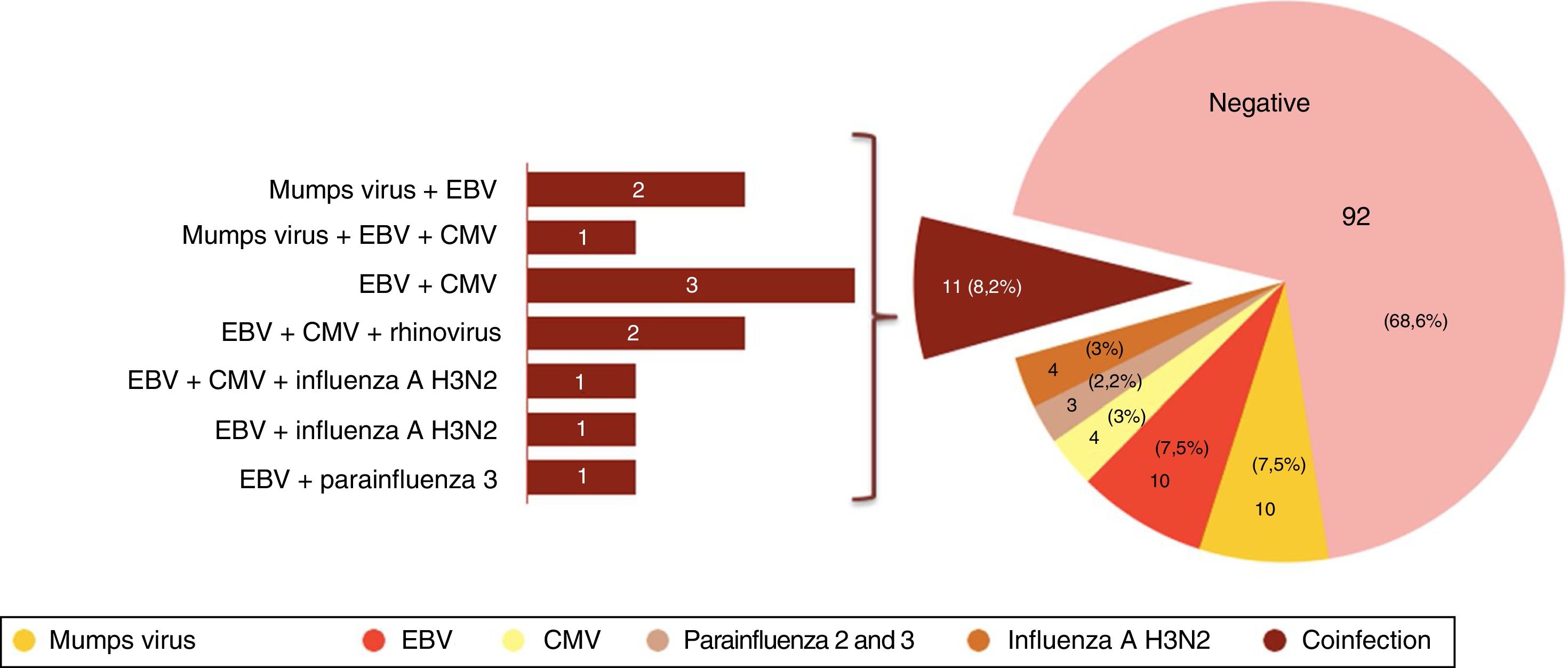

We identified 169 cases of symptomatic acute parotitis (0.21% or paediatric emergency visits). The median age of the patients was 7.7 years (range, 11 months-16.8 years). The rate of adherence to the protocol for the ordering of tests for aetiological diagnosis was 79.3%, so we were able to obtain data on testing of saliva samples from 134 patients. Fig. 1 summarises the results of PCR testing of these samples. Another 5 patients received an aetiological diagnosis of parotitis due to MuV by serologic testing (positive IgM test), adding up to a total of 18 cases caused by MuV.

The median age of patients with MuV infection (in all cases MuV genotype G) was 14.3 years (range, 18 months-16.8 years), with a predominance of the male sex (72.2%). In 3 cases (16.7%) there was no known history of contact with a case of parotitis. All patients were correctly vaccinated save for 2 children that had not received any dose of MMR by parental choice and 1 adolescent that had only received 1 dose of vaccine. There were no documented complications, except for 1 patient that developed Guillain-Barré syndrome with onset the week after the initial visit, who had a favourable outcome. The management of 19.1% of the patients included empiric antibiotherapy despite there being no evidence confirming bacterial infection.

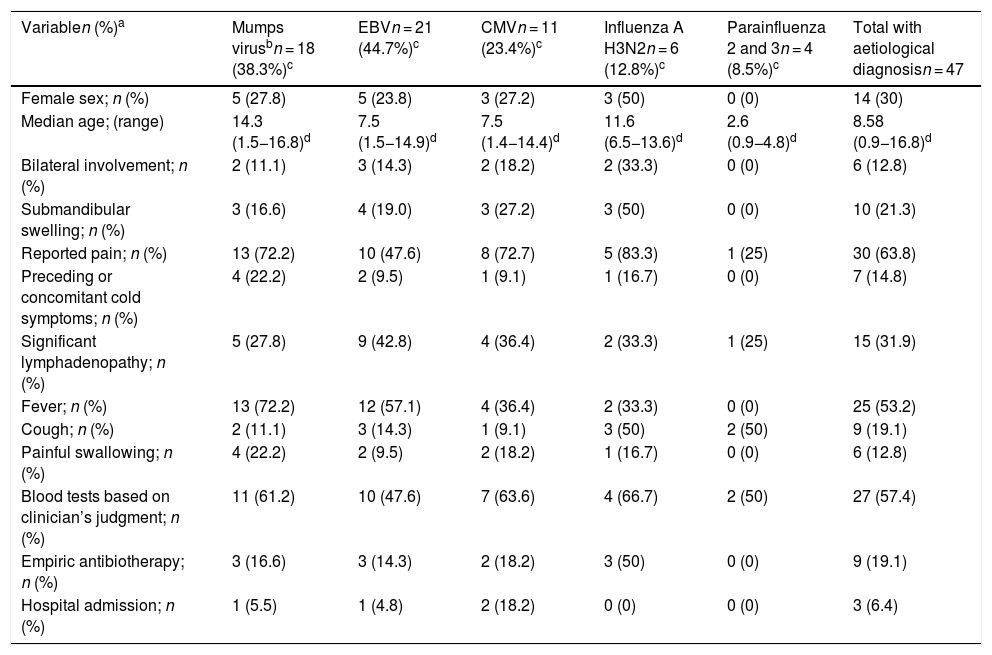

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of cases of parotitis in which testing was performed for investigation of the aetiology. Patients with MuV infection were significantly older compared to children with a different aetiological agent (median age, 14.3 vs 6.5 years; P = .005).

Summary of demographic and clinical characteristics and management of cases of parotitis with an identified aetiological agent.

| Variablen (%)a | Mumps virusbn = 18 (38.3%)c | EBVn = 21 (44.7%)c | CMVn = 11 (23.4%)c | Influenza A H3N2n = 6 (12.8%)c | Parainfluenza 2 and 3n = 4 (8.5%)c | Total with aetiological diagnosisn = 47 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex; n (%) | 5 (27.8) | 5 (23.8) | 3 (27.2) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 14 (30) |

| Median age; (range) | 14.3 (1.5−16.8)d | 7.5 (1.5−14.9)d | 7.5 (1.4−14.4)d | 11.6 (6.5−13.6)d | 2.6 (0.9−4.8)d | 8.58 (0.9−16.8)d |

| Bilateral involvement; n (%) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (12.8) |

| Submandibular swelling; n (%) | 3 (16.6) | 4 (19.0) | 3 (27.2) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 10 (21.3) |

| Reported pain; n (%) | 13 (72.2) | 10 (47.6) | 8 (72.7) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (25) | 30 (63.8) |

| Preceding or concomitant cold symptoms; n (%) | 4 (22.2) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 7 (14.8) |

| Significant lymphadenopathy; n (%) | 5 (27.8) | 9 (42.8) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (25) | 15 (31.9) |

| Fever; n (%) | 13 (72.2) | 12 (57.1) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 25 (53.2) |

| Cough; n (%) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (50) | 2 (50) | 9 (19.1) |

| Painful swallowing; n (%) | 4 (22.2) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 6 (12.8) |

| Blood tests based on clinician’s judgment; n (%) | 11 (61.2) | 10 (47.6) | 7 (63.6) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (50) | 27 (57.4) |

| Empiric antibiotherapy; n (%) | 3 (16.6) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 9 (19.1) |

| Hospital admission; n (%) | 1 (5.5) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.4) |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus.

Total: 47 patients, corresponding to 35.1% of the total patients that underwent some form of testing for aetiological investigation.

The columns devoted to each individual virus include all patients with a positive test result for that virus, including cases of coinfection.

The findings in our study, despite the limitations intrinsic to its retrospective design, were consistent with those of other authors, and showed that a significant proportion of cases of parotitis in the paediatric age group may be caused by viruses other than MuV (such as EBV, CMV and common respiratory viruses).3–5 The high frequency of cases with negative results in all tests can be explained by the involvement of other viruses that were not included in the testing (such as human herpesvirus 6), technical factors affecting the yield of microbiological diagnosis and the potential presence of non-infectious parotitis cases, among others. Viral coinfection was also frequent.

Lastly, we ought to underscore that MuV continues to be a frequent cause of parotitis in our area (especially in older children), even in correctly vaccinated patients, and our findings confirmed that the causative virus continues to circulate in the community with a well-known pattern characterised by incidence peaks every 3–5 years. The aetiological diagnosis and notification of cases can alert the health care authorities of potential outbreaks at an early stage, allowing implementation of containment measures such as administration of a third dose of vaccine in selected patients.6

Please cite this article as: Scatti-Regàs A., Aguilar-Ferrer M.C., Antón-Pagarolas A., Martínez-Gómez X., González-Peris S. Caracterización clínica y etiológica de los casos de parotiditis en un servicio de urgencias. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;93:127–129.