Sickle cell disease is an emerging anemia in Europe leading to high morbidity with severe acute complications requiring hospital admission and chronic consequences. The management of these patients is complex and needs interdisciplinary care. The objective is to analyze clinical characteristics and management of patients with sickle cell disease admitted for acute complications.

MethodsRetrospective descriptive study of admissions for acute complications of patients with sickle cell disease under 16 years of age in a tertiary hospital between 2010 and 2020. Clinical, laboratory and radiological data were reviewed.

ResultsWe included 71 admissions corresponding to 25 patients, 40% diagnosed by neonatal screening. Admissions increased during this period. The most frequent diagnoses were vaso-occlusive crisis (35.2%), febrile syndrome (33.8%) and acute chest syndrome (32.3%). Nine patients required critical care at PICU. Positive microbiological results were confirmed in 20 cases, bacterial in 60%. Antibiotic therapy was administered in 86% of cases and the vaccination schedule of asplenia was adequately fulfilled by 89%. Opioid analgesia was required in 28%. Chronic therapy with hydroxyurea prior to admission was used in 41%.

ConclusionsAcute complications requiring hospital admission are frequent in patients with sickle cell disease, being vaso-occlusive crisis and febrile syndrome the most common. These patients need a high use of antibiotics and opioid analgesia. Prior diagnosis facilitates the recognition of life-threatening complications such as acute chest syndrome and splenic sequestration. Despite the prophylactic and therapeutic measures currently provided to these patients, many patients suffer acute complications that require hospital management.

La drepanocitosis es una anemia emergente en Europa que condiciona una elevada morbilidad con complicaciones agudas y crónicas. El manejo de estos pacientes es complejo y requiere atención interdisciplinar. El objetivo del estudio es analizar las características y el manejo de los pacientes con drepanocitosis que ingresan por complicaciones agudas.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo de los ingresos por complicaciones agudas de pacientes con drepanocitosis menores de 16 años en un hospital terciario entre 2010 y 2020. Se revisaron los datos clínicos, analíticos y radiológicos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 71 ingresos correspondientes a 25 pacientes, el 40% diagnosticados por cribado neonatal. Los ingresos se incrementaron de forma progresiva durante este periodo. Los diagnósticos más frecuentes fueron la crisis vasooclusiva (35,2%), el síndrome febril (33,8%) y el síndrome torácico agudo (32,3%). Nueve pacientes precisaron ingreso en cuidados intensivos. En 20 ingresos se obtuvo documentación microbiológica, 60% bacterias. En el 86% se administró antibioterapia y 28% precisaron analgesia con opioides. El 89% cumplían la pauta de vacunación adecuada y el 41% recibían hidroxiurea previo al ingreso.

ConclusionesLas complicaciones agudas que precisan ingreso hospitalario son frecuentes en los pacientes con drepanocitosis, siendo las más habituales la crisis vasooclusiva y el síndrome febril. Esto conlleva un uso elevado de antibioterapia y opioides. El diagnóstico precoz facilita el reconocimiento de complicaciones de riesgo vital como el síndrome torácico agudo y el secuestro esplénico. A pesar de las medidas preventivas y los tratamientos indicados en la actualidad, estas complicaciones agudas precisan manejo hospitalario.

Sickle-cell disease (SCD), also known as drepanocytosis, is the most prevalent autosomal recessive structural haemoglobinopathy worldwide. It is caused by a point mutation in the gene encoding the beta globin chain, the product of which, known as haemoglobin S, (HbS), is less soluble than adult haemoglobin (HbA) and foetal haemoglobin (HbF).1 The term SCD includes comprises disorders with the HbS variant in both alleles (HbSS) or in coinheritance with another variant in the other beta globin allele (HbS-β thalassaemia, HbSC…).2,3

The lower solubility of HbS facilitates its polymerization under hypoxic conditions, leading to the formation of the sickle-shaped red blood cells. At the level of the microvasculature, this morphological abnormality gives rise to vaso-occlusive phenomena and haemolytic anaemia, responsible for the main acute and chronic complications of this disease, including acute chest syndrome (ACS), splenic sequestration, stroke and pain and vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs). At the level of the spleen, repeated vessel occlusion causes hyposplenism at a young age and an increased risk of infection, particularly by encapsulated bacteria.4

Sickle cell disease is considered a global health problem by international organizations such as the United Nations and the World Health Organization. The most affected regions are Sub-Saharan Africa and tropical regions in Asia and America. However, in recent decades population migration patterns have led to the emergence of the disease in European countries and North America.5 In Spain, the data of the register of haemoglobinopathies of the Sociedad Española de Hemato-Oncología Pediátrica (Spanish Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology, SEHOP) shows an increase in the number of reported cases. In addition, since 2003, the number of new cases in individuals born in Spain exceeds the number of imported cases.6

Sickle cell disease is included in the routine newborn screening programme implemented universally in Spain. Specifically, it was first introduced in the screening programme of the Basque Country in 2011. These screening data are consistent with the data of the SEHOP register, showing an increase from 0.28 cases per1000 live births in 2012 to 0.42 per 1000 live births in 2018.7,8

Newborn screening allows early detection of SCD and the implementation of preventive measures (vaccination, antimicrobial prophylaxis and health education for families) that have been shown to improve survival and quality of life in several studies.3,9,10 Furthermore, the addition of hydroxyurea to the routine management of patients with SCD based on the results of the BABY-HUG trial (2011)11–13 has achieved a marked decrease in episodes of pain and hospitalization and an improvement in laboratory parameters.

The aim of our study was to analyse the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with SCD who required hospital admission due to acute complications.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective descriptive study of hospital admissions of paediatric patients with SCD from January 2010 to December 2020.

We included all admissions to the inpatient ward and to the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) of patients with SCD due to acute events associated with their underlying disease. The exclusion criteria were admission for scheduled interventions or performance of diagnostic tests, admissions in other hospitals, and age at admission equal to or greater than 16 years.

We retrieved data from the electronic health records of the patients. We collected data on epidemiological and clinical characteristics (sex, age at admission, disease phenotype and association with other haemoglobinopathies, family history and newborn screening), diagnostic tests performed and treatments received during the hospital stay.

We collected the data and analysed it with the software SPSS version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Most variables were categorical and expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages. We made comparative analyses using the χ² and the Fisher exact test. Quantitative variables were summarised as mean and standard deviation (SD) and analysed by means of the Student t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) if the data followed a normal distribution. Otherwise, we summarised them as median and interquartile range (IQR) and analysed the data using the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance as defined as a p-value of less than 0.05.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with medicines of the Basque Country as part of the “Spanish Paediatric Register of Haemoglobinopathies of the SEHOP, Epidemiology of haemoglobinopathies in Spain.”

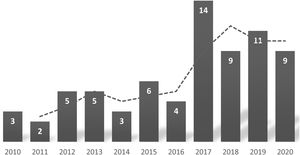

ResultsGeneral characteristicsDuring the period under study, a total of 35 patients with SCD were in followup in our hospital, and there were 71 admissions corresponding to 25 patients. The mean number of admissions per year was 2.8, with substantial variation (6 patients were admitted only once, and 1 was admitted 8 times). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the sample. We did not find significant differences in the sex distribution of the hospital admissions or the total sample of patients. Fig. 1 shows that there was an increase in the number of admissions per year. In the 11-year period under study, 7 patients were lost to followup.

Sample characteristics.

| Patients | n = 25 | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 11 | 44 |

| Male | 14 | 56 | |

| Diagnosed through screening | Yes | 10 | 40 |

| No | 15 | 60 | |

| Phenotype | HbSS | 23 | 92 |

| HbSC | 2 | 8 | |

| Born in Spain | Yes | 17 | 68 |

| No | 5 | 20 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 12 | |

| Parents | n = 50 | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continent of origin | Africa | 44 | 88 |

| Asia | 2 | 4 | |

| America | 2 | 4 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 4 |

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current age | 9.36 | 4.39 | 0.7−16.6 |

| Age at diagnosisa | 1.65 | 1.29 | 0.4−5.1 |

The most frequent diagnosis at admission were, in decreasing order, VOC, febrile illness, ACS and splenic sequestration. Eight patients presented with ACS associated with VOC. Other diagnoses included malaria (1 case) and anaemia (2 cases). Table 2 presents the reasons for admission in relation to the disease phenotype.

Reasons for admission by phenotype.

| Reason for admission | HbSS | HbSC | P | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 61) | (n = 10) | (n = 71) | ||

| Vaso-occlusive crisis | 26.2% (16) | 10% (1) | ns | 23.9% (17) |

| Acute chest syndrome | 16.4% (10) | 50% (5) | 0.014 | 21.1% (15) |

| Acute chest syndrome + vaso-occlusive crisis | 11.5% (7) | 10% (1) | ns | 11.3% (8) |

| Febrile syndrome | 36.0% (22) | 20% (2) | ns | 33.8% (24) |

| Splenic sequestration | 4.9% (3) | 10% (1) | ns | 5.6% (4) |

| Other | 4.9% (3) | 0% (0) | ns | 4.2% (3) |

ns: not significant.

The mean age at admission was 5.7 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.7–6.8), and the range was 1 month to 15.1 years. The median age at the time of the first admission was 1.7 years. Splenic sequestration occurred in younger patients compared to the rest of diagnoses (1.7 years [95% CI, 0–5.3] vs 5.9 years [95% CI, 4.8–6.9]; P = 0.02), while VOCs occurred in older children (8.8 years [95% CI, 7.3–10.3] vs 4.0 years [95% CI, 2.8–5.1]; P < 0.001). In 88.7% of admissions (n = 63) patients were correctly vaccinated. In 71.8% (n = 51) patients were receiving penicillin for antimicrobial prophylaxis, including 83.8% of patients aged less than 6 years and 58.8% of patients aged 6 or more years. In 67.1% of the care episodes, patients were in treatment with folic acid and in 41.4% with hydroxyurea. One patient was managed with a hypertransfusion regimen after experiencing 3 episodes of splenic sequestration in the first 12 months of life.

The median length of stay was 6 days (IQR, 4–8]. As can be seen in Table 3, the combination of VOC and ACS was associated with longer stays compared to isolated ACS (P = 0.046).

Clinical and laboratory features by diagnosis.

| Total | VOC | ACS | ACS + VOC | FI | SS | Other | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | 100% (71) | 23.9% (17) | 21.1% (15) | 11.3% (8) | 33.8% (24) | 5.6% (4) | 4.2% (3) | |

| Length of stay (days)a | 6.78 ± 5.53 | 7.38 ± 7.58 | 5.33 ± 2.35 | 11.88 ± 6.42 | 5.61 ± 3.56 | 6.00 ± 2.45 | 1.67 ± 0.58 | 0.014 |

| Age at admission (years)a | 5.55 ± 4.28 | 8.13 ± 3.98 | 4.45 ± 4.00 | 9.4 ± 1.6 | 3.77 ± 3.93 | 1.67 ± 2.27 | 5.97 ± 3.82 | 0.014 |

| Minimum Hb (g/dL)a | 7.11 ± 1.82 | 7.49 ± 1.54 | 7.80 ± 0.87 | 6.76 ± 1.42 | 7.22 ± 1.65 | 2.68 ± 1.93 | 6.43 ± 0.85 | <0.001 |

| Maximum CPR (mg/L)a | 78.74 ± 76.51 | 60.90 ± 69.34 | 128.89 ± 86.00 | 126.08 ± 76.62 | 56.70 ± 59.51 | 15.44 ± 16.15 | 11.89 ± 14.11 | 0.004 |

| Fever | 73.2% (52) | 35.3% (6) | 80% (12) | 87.5% (7) | 100% (24) | 50% (2) | 33.3% (1) | <0.001 |

| Microbial isolation | 28.2% (20) | 11.8% (2) | 40% (6) | 25% (2) | 29.2% (7) | 50% (2) | 33.3% (1) | ns |

| Performance of chest X-ray | 66.2% (47) | 17.6% (3) | 100% (15) | 100% (8) | 62.5% (15) | 75% (3) | 100% (3) | <0.001 |

| Abnormal chest X-ray | 35.2% (25) | 0% (0) | 100% (15) | 100% (8) | 6.7% (1) | 25% (1) | 0% (0) | <0.001 |

| Antibiotherapy | 85.9% (61) | 64.7% (11) | 100% (15) | 100% (8) | 95.8% (23) | 75% (3) | 33.3% (1) | 0.001 |

| Transfusion | 25.4% (18) | 5.9% (1) | 13.3% (2) | 37.5% (3) | 29.2% (7) | 100% (4) | 33.3% (1) | 0.004 |

| Oxygen therapy | 28.2% (20) | 11.8% (2) | 40% (6) | 100% (8) | 8.3% (2) | 50% (2) | 0% (0) | <0.001 |

| Opioids | 28.2% (20) | 58.8% (10) | 0% (0) | 87.5% (7) | 12.5% (3) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | <0.001 |

| Hyperhydration | 25.4% (18) | 58.8% (10) | 26.7% (4) | 12.5% (1) | 1.52% (3) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0.008 |

| Admission to PICU | 12.7% (9) | 11.8% (2) | 6.7% (1) | 25% (2) | 8.3% (2) | 50% (2) | 0% (0) | ns |

ACS, acute chest syndrome; FI, febrile illness; Hb, haemoglobin; ns, not significant; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit SS, splenic sequestration; VOC, vaso-occlusive crisis.

There were a total of 9 admissions to the PICU (12.6%), corresponding to 4 patients. admission to the PICU was required in 50% of cases of splenic sequestration compared to 10.4% of the rest of acute complications (OR, 8.6; 95% CI, 1.0–70.7; P = 0.02). The main reason for admission to the PICU was severe VOC, defined by association of ACS, infection or intractable pain (55.5%). Two of the patients were admitted due to hypovolaemic shock with severe anaemia secondary to splenic sequestration, and another with ACS requiring respiratory support. One patient required admission due to late-onset sepsis caused by Streptococcus agalactiae. None required invasive mechanical ventilation, inotropic support or red blood cell exchange apheresis.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics (Table 3)Fever was present in 52 admissions. The C-reactive protein (CRP) level was greater than 20 mg/L in 63.4% (n = 45) of admissions. The elevation of CPR was greater in patients with ACS compared to the rest of the patients (123.1 mg/L [95% CI, 87.9–158.3] vs 53.3 mg/L [95% CI, 36.6–73.5]; P < 0.001).

The mean minimum haemoglobin concentration during the stay was 7.1 g/dL (95% CI, 6.6–7.5), and was significantly lower in patients with splenic sequestration compared to the rest (2.7 g/dL [95% CI, 0–5.7] vs 7.3 g/dL [95% CI, 6.9–7.7]; P < 0.001). A chest radiograph was performed in 47 episodes, and the most frequent finding was unilateral consolidation (15 cases) as opposed to bilateral involvement (10 cases). Pathogens were isolated in 20 episodes (28.2%), the details of which are given in Table 4. In 33% of admissions due to ACS and febrile illness, there was microbiological isolation of a pathogen, and the difference compared to all other diagnoses (17.2%) was not statistically significant. Most episodes of ACS were triggered by respiratory viruses, with microbiological confirmation. Parvovirus B19 caused an aplastic crisis in 2 patients. One infant had late-onset sepsis caused by Streptococcus agalactiae.

Microbiological results.

| Microbial isolation (n = 20) | n | Pathogen | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria (n = 11) | |||

| Gram-positive cocci | 6 | CNS | 3 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 1 | ||

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 1 | ||

| Streptococcus viridans | 1 | ||

| Gram-negative bacilli | 5 | Salmonella spp | 4 |

| Acinetobacter | 1 | ||

| Virus (n = 7) | |||

| Respiratory viruses | 5 | RSV + rhinovirus | 2 |

| Adenoviridae | 1 | ||

| Influenzavirus A | 1 | ||

| Parainfluenza + enterovirus | 1 | ||

| SARS COV-2 | 1 | ||

| Other viruses | 2 | Parvoviridae B19 | 2 |

| Other | 1 | Plasmodium falciparum | 1 |

CNS, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

In 85.9% of the episodes (n = 61), patients received antibiotherapy, in most cases (42; 68.9%) with a combination of drugs. The most frequently prescribed antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins (59; 96.2%), followed by macrolides (24; 39.3%) and other beta-lactam antibiotics (20; 32.8%). Macrolides were generally used in combination with a cephalosporin or other beta-lactam antibiotics. Two patients received oseltamivir, in 1 to treat a confirmed infection by influenzavirus and in 1 for empirical treatment during the flu season.

Oxygen therapy was used in 20 episodes (28.2%), more frequently in patients with ACS compared to all other diagnoses (62.5% vs 10.6%; OR, 14.0 [95% CI, 4.0–48.5]; P < 0.001). One patient required non-invasive ventilation and another high-flow oxygen therapy. Three patients with ACS required bronchodilators.

Opiates were used for analgesia in 20 admissions (28.2%), more frequently in patients with VOC compared to the rest of the sample (68% vs 6.5%; OR, 30.5 [95% CI, 7.2–128.7]; P < 0.001). Two patients with febrile illness required fixed doses of opioids to treat abdominal pain in episodes that did not quite meet the criteria for VOC. Ten patients with VOC received opiates in continuous infusion.

In 18 care episodes (25.4%) the patient received at least 1 red blood cell transfusion, and in 2 cases the patient developed a post-transfusion reaction. In the 4 admissions due to splenic sequestration, the patients required treatment with blood products.

Since the beginning of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, 1 patient has been admitted due to SARS-CoV2 infection with bilateral pneumonia. The patient received treatment with lopinavir-ritonavir, heparin, steroids and low-flow oxygen therapy per the current protocols in April 2020, and had a favourable outcome.

There were no cases of stroke or deaths in the hospitalised patients under study. Furthermore, none of the patients died while receiving care in the emergency department.

DiscussionPatients with SCD are at high risk of severe acute complications requiring hospital admission, at times in the intensive care unit. The differential diagnosis and management of these patients are complex and require a multidisciplinary approach.14

The main reason for admission was VOC, which was consistent with past descriptions.15 These were moderate and severe VOCs that did not respond to the usual analgesic treatment given at home and therefore required opiates in a high percentage of cases. We ought to mention that one third of patients admitted for VOC developed ACS as a secondary complication, and that the need of opioids was greater in these patients. This association has been extensively documented and could be due to an interaction of different pathogenic mechanisms (release of fat embolisms to the blood flow due to bone marrow necrosis, occlusion and necrosis of pulmonary microvasculature and hypoventilation/atelectasis secondary to pain and/or opioid therapy).16–18 When both of these complications co-occur, there is an increase in morbidity and the length of stay.16–18 However, the clinical and laboratory features associated with an increased risk of developing this secondary complication are not known.16 Some of the strategies proposed for the prevention of ACS by the Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátricas (Spanish Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology, SEHOP)19 are optimization of the management of the pain caused by VOCs, vital signs monitoring, respiratory physical therapy with incentive spirometry and early mobilization.

Another frequent complication was febrile illness requiring intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotherapy. Given the functional asplenia and immunosuppression experienced by these patients, specific vaccination schedules must be established, and the increased risk of severe bacterial infection must be taken into account. A salient finding in our series was that third-generation cephalosporins were the main agents used in antibiotherapy. There was evidence of lung consolidation in nearly half of the chest radiographs performed, posing a challenge in the differential diagnosis between pneumonia and ACS.

A large percentage of patients received antibiotherapy during the stay, in more than 2/3 combining different classes of antibiotic drugs. This approach is consistent with current management guidelines due to the increased risk of infection by encapsulated bacteria. However, this frequent use of antibiotherapy stands in contrast with the frequency of bacterial isolation in our sample (Table 4). Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b or Neisseria meningitidis were not isolated in any episode, probably due to the routine vaccination schedule and antibiotic prophylaxis. We ought to highlight the isolation of Salmonella spp in one third of the bacterial infections. The factors that increase the susceptibility to these pathogens are functional asplenia, defective opsonization and disorders of humoral immunity.20 The second most frequent microbial agents were respiratory viruses, most of which were detected in the context of ACS.

In our study, only one patient with SCD required admission due to bilateral pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV2, who had a favourable outcome with the prescribed treatment, as described in previous publications.21 Recent studies suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on the followup of patients with SCD, with decreased adherence to screening guidelines and routine use of telemedicine.22

A large percentage of patients was correctly vaccinated and received the indicated antibiotic prophylaxis. Some of the causes for incomplete vaccination status were the barriers to adherence to preventive measures in this subset of the population, language barriers, lack of awareness about the disease and frequent changes of address and travel to the country of origin.23

Of all life-threatening complications, we ought to highlight splenic sequestration. Although this is an infrequent complication, early detection is crucial, as it is a medical emergency with a high risk of hypovolaemic shock due to the trapping of blood in the spleen. It typically occurs in children aged 3 months to 2 years whose spleens have not yet developed fibrosis from repeated splenic infarction, and the rate of recurrence is high.19 In our sample, 3 of the 4 episodes of splenic sequestration occurred in a single female patient that had onset at 2.5 months post birth with hypovolaemic shock (minimum haemoglobin, 1.3 g/dL) and splenomegaly. Thanks to the previous diagnosis of SCD through the newborn screen, it was suspected early and treated immediately. Subsequently, she had additional episodes at 5 and 11 months post birth. After that, she started a hypertransfusion regimen to prevent new episodes with chelation therapy with deferasirox from age 19 months. Half of episodes of splenic sequestration required admission to the PICU, and there were no deaths. The documented morbidity was similar to what has been described in other case series.24

The majority of patients in our study were the first generation born in Spain, and more than 90% had parents from the African continent. This was consistent with previous studies conducted in Spain,6 which is currently a destination country for immigration from regions where SCD is endemic.25 These migration patterns have led to an increase in the diagnosis of SCD in children and the number of annual hospitalizations due to acute complications of the disease (Fig. 1). The increase in cases diagnosed in Spain in recent years5,6 has motivated a growing interest in improving the management of SCD and the development of management protocols based on current evidence and expert recommendations.19

Although most patients were born in Spain, only slightly more than one third were diagnosed through the newborn screening, a similar proportion to that reported in the latest update of the Spanish haemoglobinopathy register.26 This is because some of the patients were born in areas where newborn screening programmes had yet to be introduced in the public health system. At present, it is implemented in every autonomous community in Spain, but it is still important to maintain a high level of suspicion in immigrant patients from endemic regions where screening is not performed. Early diagnosis facilitates the recognition of life-threatening complications, such as ACS and splenic sequestration, as evinced in this case series. Furthermore, early implementation of preventive measures contributes to reducing the incidence of severe complications and improves long-term survival.14

During the study followup, recommendations changed regarding treatment with hydroxyurea in the paediatric population. Until 2011, this treatment was restricted to patients with recurrent complications, so the percentage of patients that received it was smaller in the first years under the study. At present, initiation of hydroxyurea is recommended in patients with SCD (HbSS or beta-thalassemia) from 9 months, even in asymptomatic patients.11–13 In this series, we reviewed admissions in the past 11 years and included patients with heterozygous SC phenotypes and aged less than 9 months, so that only 40% were receiving this treatment at the time of admission. In recent years, treatment with hydroxyurea has been expanded to all patients with HbSS or S beta phenotypes, although there is evidence of poor adherence to treatment in some patients.

The main limitations of our study are those derived from its retrospective design and the impact of recent modifications to clinical practice guidelines.19 In addition, the characteristics of this population (frequent changes of residence, low awareness of the disease…) may result in an underestimation of the actual complications, some of which may have been managed in other clinics or led to admission in other hospitals, as well to losses to followup.

In conclusion, SCD is an emerging disease in our region that causes acute complications that frequently require admission and multiple treatments. Early diagnosis through newborn screening, preventive measures and the treatments currently prescribed improve the prognosis of the disease, decreasing morbidity in the short and long terms. Therefore, the followup of these patients must be integrated in every level of care in the health system (primary care and hospital-based care) to improve adherence to treatment and to preventive measures.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank patients and families for their collaboration, as well as the entire team of paediatricians and nurses in charge of their care, both at hospital and at the primary care level.

Both authors have contributed equally to this work.

Please cite this article as: Reparaz P, Serrano I, Adan-Pedroso R, Astigarraga I, de Pedro Olabarri J, Echebarria-Barona A, et al. Manejo clínico de las complicaciones agudas de la anemia falciforme: 11 años de experiencia en un hospital terciario. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;97:4–11.