Deep neck space abscesses in infants are clinical entities of great importance due to their severity and possible complications. The aim of the study is to review our experience in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of deep neck space abscesses, and compare it with published literature.

Material and methodsRetrospective study was carried out on all patients diagnosed and treated for deep neck space abscesses over a 15-year period (2002–2016), including an analysis of the demographic, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic characteristics.

ResultsA total of 72 cases were diagnosed. An increase was observed in their incidence in recent years. The most frequent locations were peri-tonsillar (30.6%), followed by swollen lymph nodes (18.1%), parapharyngeal (16.7%), and retropharyngeal (16.7%). The least frequent were submandibular abscesses (12.5%) and parotid abscesses (5.6%). The distribution was different according to age (P<.001). The most frequent clinical symptom was fever (70.8%), followed by odynophagia (55.56%). The most used imaging tests were CT (50.7%) and ultrasound (28.2%). The treatment used was pharmacological in 11.1%, all of them abscessed swollen lymph nodes of less than 1.5cm in maximum size. The other 88.9% underwent surgery. There was recurrence in 12.5% of the cases.

ConclusionsThe performance of tonsillectomy and/or early cervicotomy in abscesses larger than 2cm or lesions of deep location decreases the number of serious complications and does not have recurrences. When using more conservative surgery, there were 12.5% of recurrences.

Los abscesos cervicales profundos infantiles son entidades clínicas de gran importancia por su gravedad y sus posibles complicaciones. El objetivo del estudio es revisar nuestra experiencia en el manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico de los abscesos cervicales profundos infantiles, y compararla con la literatura publicada.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de todos los pacientes diagnosticados y tratados de abscesos cervicales profundos infantiles durante 15 años (2002-2016), analizando las características demográficas, clínicas, diagnósticas y terapéuticas.

ResultadosSetenta y dos casos fueron diagnosticados. Se aprecia un incremento de su incidencia en los últimos años. La localización más frecuente han sido los abscesos periamigdalinos (30,6%), seguido de las adenopatías abscesificadas (18,1%), los abscesos parafaríngeos (16,7%) y los retrofaríngeos (16,7%). Las menos frecuentes han sido los abscesos submandibulares (12,5%) y parotídeos (5,6%). La distribución fue diferente según edad (p<0,001). El síntoma clínico más frecuente ha sido la fiebre (70,8%), seguido de la odinofagia (55,56%). Las pruebas de imagen más utilizadas han sido la TAC (50,7%) y la ecografía (28,2%). El tratamiento empleado fue farmacológico en el 11,1%, todos ellos adenopatías abscesificadas menores de 1,5cm de tamaño máximo. El otro 88,9% fue intervenido quirúrgicamente. Hubo recidiva en el 12,5% de los casos.

ConclusionesLa realización de amigdalectomía y/o cervicotomía precoz en abscesos mayores de 2cm o lesiones de localización profunda disminuye el número de complicaciones graves y no presenta recidivas. Al utilizar cirugía más conservadora, se han encontrado un 12,5% de recidivas.

Paediatric deep neck abscesses (PDNAs) are infrequent in clinical practice, yet important on account of their severity and potential complications, as they may even be life-threatening.1 Recent studies have reported an increase in their incidence in the past few years.1,2

The clinical presentation of PDNAs is nonspecific.3,4 The most common symptoms are fever or painful swallowing, while others that are more indicative of the problem, such as the presence of a mass or a limited range of motion, are less frequent. This complicates their diagnosis, which in some cases leads to serious problems, such as upper airway obstruction.1,4

Computed tomography (CT) and ultrasound of the neck are the imaging tests used most frequently to diagnose PDNAs.3–5 The use of lateral neck radiographs is decreasing steadily, while the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been increasing.

When it comes to treatment, there seems to be no clear consensus in the medical literature, with many groups favouring a highly conservative approach to treatment6,7 and resorting to surgery only in cases of clinical worsening despite treatment, respiratory compromise or abscesses larger than 2cm.4,8 Few studies specify the type of surgery used or the advantages and disadvantages of each surgical approach.

Few case series have been published in the literature on the subject of PDNAs, with small samples, differences in the methodology used and classifications that may be confusing due to the use of exclusively anatomical, radiological or clinical criteria. The aim of our study was to describe our experience with this health problem in the past 15 years, analysing aspects relating to its clinical presentation, classification, diagnosis and management.

Materials and methodsWe present a retrospective observational study of the results obtained through the review of patients with PDNA admitted and managed in the paediatric otorhinolaryngology unit (the referral unit for the entire province) of the department of otorhinolaryngology of a tertiary care hospital over a period of 15 years (2002–2016).

We included children aged 0–15 years with a diagnosis of PDNA, excluding patients with inflammatory processes that did not result in the development of an abscess, congenital malformations or with odontogenic or retromastoidal abscesses.

We classified cases of PDNA from both an anatomical and a diagnostic/therapeutic perspective, adapting the criteria published by the Sociedad Española de Otorrinolaringología y Patología Cérvico-Facial (Spanish Society of Otorhinolaryngology and Cervical and Facial Disorders).9 Thus, we categorised PDNAs by location as lymph node abscess (LNA), parapharyngeal abscess (PPA), retropharyngeal abscess (RPA), parotid abscess (AP), submandibular abscess (SA) or peritonsillar abscess (PTA). We considered the submandibular location as a separate location because it is the most common site of abscesses caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria.

We grouped cases by type of treatment into medical treatment (no surgical intervention), incision and drainage (incision in the lesion to drain the abscess) tonsillectomy (surgical removal of palatine tonsils) and cervicotomy (surgery exposing the deep spaces of the neck).

The variables under study were age, sex, use of antibiotics prior to admission, location of the abscess (LNA, PPA, RPA, AP, SA or PTA), symptoms, length of stay in days, imaging tests performed, size of the abscess, treatment used, complications, abscess recurrence and its treatment, results of bacteriological testing, results of pathological examination and treatment after discharge.

We divided the sample into 3 age groups based on the specific clinical, immunologic, anatomical and management characteristics of the patients: 0–2 years, 3–6 years and 7–15 years.

In this study, we adhered to national and international ethics guidelines, and did not engage in any clinical intervention outside approved protocols. We anonymised all the data, removing identifiable information.

We calculated absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables and the mean and standard deviation or the median and interquartile range for quantitative variables based on whether their distribution was normal. The data were analysed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM-SPSS, 2000) version 25.0 and Epidat version 3.1; we defined statistical significance as a P-value of less than .05.

ResultsIn the 15-year period under study, there were 72 cases of PDNA, with a mean frequency of 4.8 cases/year and an increase in the past 7 years, with the incidence reaching 6 cases/year. Of all cases, 48.6% occurred in female patients, and the mean age of onset was 6 years (0.33–14.83 years). Table 1 summarises the clinical characteristics of the patients.

Characteristics of paediatric patients with deep neck abscesses (n=72).

| n (%)Mean±SD | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 37 (51.4) |

| Female | 35 (48.6) |

| Mean age (years) | 6±4.7 |

| Previous antibiotic treatment | 32 (44.4) |

| Location | |

| Lymph node abscess (LNA) | 13 (18.1) |

| Parapharyngeal abscess (PPA) | 12 (16.7) |

| Retropharyngeal abscess (RPA) | 12 (16.7) |

| Parotid abscess (PA) | 4 (5.6) |

| Submandibular abscess (SA) | 9 (12.5) |

| Peritonsillar abscess (PTA) | 22 (30.6) |

| Clinical features | |

| Fever | 51 (70.8) |

| Painful swallowing | 40 (55.6) |

| Cervical mass | 34 (47.2) |

| Restricted motion | 12 (16.7) |

| Length of stay (days) | 7.0±4.6 |

| Imaging tests | |

| Lateral radiograph | 8 (11.3) |

| CT scan | 36 (50.7) |

| Ultrasound | 20 (28.2) |

| MRI scan | 7 (9.9) |

| Mean abscess diameter (cm) | 2.9 |

| Treatment | |

| Medical | 8 (11.1) |

| Surgical | 64 (88.9) |

| Drainage | 29 (40.8) |

| Tonsillectomy | 26 (36.6) |

| Cervicotomy | 9 (12.7) |

| Complications | |

| Recurrence | 10 (12.5) |

| Death | 0 (0) |

| Microbiological culture | |

| No pathogen growth | 7 (37.0) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3 (15.8) |

| Acid-fast bacteria | 2 (10.5) |

| Other | 8 (42.1) |

| Antibiotherapy after discharge | 71 (98.6) |

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SD, standard deviation.

Of the 72 patients with PDNA, 55.6% had not received antibiotic treatment previous to admission, while 44.4% did receive it; beta-lactam agents were the most frequent type used (26% of cases).

When it came to the type of abscess by location, the most frequent type was PTA, found in 22 patients (30.6%), followed by LNA in 13 (18.1%), PPA in 12 (16.7%) and RPA in 12 (16.7%). The least frequent locations were SA, found in 9 patients (12.5%) and PA, found in 4 (5.6%).

Table 2 presents the distribution of PDNAs by location and age group, showing substantial differences between groups (P<.001).

Distribution of the different types of PDNA by age group.

| 0–2 years (n=22); n (%) | 3–6 years (n=30); n (%) | 7–15 years (n=20); n (%) | Total (n=72); n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node abscess | 5 (22.7) | 7 (23.3) | 1 (5) | 13 (18) |

| Parapharyngeal abscess | 3 (13.6) | 7 (23.3) | 2 (10) | 12 (16.7) |

| Retropharyngeal abscess | 4 (18.2) | 7 (23.3) | 1 (5) | 12 (16.7) |

| Parotid abscess | 3 (13.6) | 1 (3.3) | – | 4 (5.5) |

| Submandibular abscess | 6 (27.3) | 3 (10) | – | 9 (12.5) |

| Peritonsillar abscess | 1 (4.5) | 5 (16.7) | 16 (80) | 22 (30.5) |

PDNA, paediatric deep neck abscess.

Chi square test, P<.001.

The most frequent presenting symptom in the sample was fever, found in 51 patients (70.8%), followed by painful swallowing in 40 patients (55.6%), a cervical mass in 34 (47.2%) and limited neck motion in 12 (16.7%). The laboratory parameters under study included leucocytosis, with a median of 15000cells/mL (11700–19000) and the serum CPR level, with a median of 3.85mg/L (1.37–11.67). The mean length of stay was 7 days (2–33). Table 3 presents the distribution of these variables by location of PDNA.

Distribution of clinical features by location of PDNA.

| Lymph node abscess | Parapharyngeal abscess | Retropharyngeal abscess | Parotid abscess | Submandibular abscess | Peritonsillar abscess | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, media (SD) | 4.1 (3.3) | 5 (2.3) | 3.7 (3.1) | 2.4 (2.4) | 2.8 (2) | 10.9 (4.4) | 6 (4.7) |

| Length of stay in days, mean (SD) | 6.3 (2.1) | 6.8 (2.1) | 7.5 (2.5) | 7.2 (2.1) | 12.6 (9.6) | 3.4 (1) | 7.0 (4.6) |

| Fever, n (%) | 13 (100) | 5 (41.6) | 5 (41.6) | 3 (75) | 7 (77.7) | 18 (81.8) | 51 (70.8) |

| Painful swallowing, n (%) | 7 (53.8) | 4 (33.3) | 9 (75) | 3 (75) | 3 (33.3) | 14 (63.6) | 49 (55.5) |

| Mass, n (%) | 13 (100) | 6 (50) | 2 (16.6) | 4 (100) | 9 (100) | 0 | 34 (47.2) |

| Restricted neck motion, n (%) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (16.6) | 4 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 4 (18.1) | 12 (16.6) |

| WBC count (cells/mL), median (IQR) | 12000 (7200) | 12300 (5450) | 13600 (3900) | 13000 (3000) | 21000 (6550) | 16500 (5000) | 15000 (7300) |

| CRP (mg/L), median (IQR) | 2 (6.3) | 0.8 (0.8) | 3.8 (3.2) | 8.7 (5) | 4.4 (12.5) | 11.7 (3.7) | 3.9 (10.3) |

CPR, C-reactive protein; IQR, interquartile range; PDNA, paediatric deep neck abscess; SD, standard deviation; WBC, white blood cell.

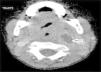

We reviewed the results of 71 imaging tests performed in 63 patients. The imaging tests used most frequently were CT scans, performed in 36 patients (50.7%), followed by ultrasound examinations in 20 (28.2%), lateral neck radiographs in 8 (11.3%) and MRI scans in 7 (9.9%). In 62.5% (5 out of 8) of patients initially assessed with a lateral neck radiograph and 15% (3 out of 20) of patients assessed with ultrasound, performance of a CT or MRI scan was necessary to complete the evaluation. Patients initially assessed by means of CT or MRI did not require additional imaging tests. Computed tomography was used mainly to assess abscesses in deeper locations (RPA, PTA and PPA), while ultrasound was used to assess more superficial abscesses (LNA and SA) (Figs. 1 and 2).

We analysed the longitudinal diameter of the abscess on CT images and calculated the mean value, comparing patients treated surgically to those who did not undergo surgery. We found an overall mean PDNA size of 2.9cm (SD, 1.9), with a mean of 1.4cm in patients that did not undergo surgery (SD, 0.3) and of 5.1cm in patients treated surgically (SD, 1.2).

The management was medical with antibiotherapy in 8 cases (11.1%), all of them LNAs with a maximum diameter of less than 1.5cm. The management was surgical in the remaining 64 cases (88.9%), but since there were 10 recurrences, there were a total of 74 operations. Table 4 presents the types of surgery that achieved a cure (that is, excluding interventions after which the PDNA recurred), showing the different surgical interventions used based on the type of abscess (P<.001).

Type of surgical intervention by location of PDNA.

| Lymph node abscess (n=13) | Parapharyngeal abscess (n=12) | Retropharyngeal abscess (n=12) | Parotid abscess (n=4) | Submandibular abscess (n=9) | Peritonsillar abscess (n=22) | Total (n=72) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incision/drainage, n (%) | 4 (30.7) | 1 (8.3) | 8 (66.7) | 4 (100) | 6 (66.7) | 6 (27.3) | 29 (40.8) |

| Tonsillectomy, n (%) | 1 (7.7) | 8 (66.7) | 2 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 15 (68.2) | 26 (36.6) |

| Cervicotomy, n (%) | 0 | 3 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0 | 3 (33.4) | 1 (4.5) | 9 (12.7) |

| Total operated, n (%) | 5 (38.5) | 12 (100) | 12 (100) | 4 (100) | 9 (100) | 22 (100) | 64 (89.9) |

PDNA, paediatric deep neck abscess.

Chi square, P<.001.

The most frequent complication was recurrence of the PDNA. There were 10 recurrences in 9 patients (1 patient experienced 2 recurrences), amounting to a proportion of recurrence in children with PDNA of 12.5%. The 10 recurrences developed in patients treated with incision and drainage, and the recurrence was treated with incision and drainage in 4 cases, tonsillectomy in another 4 and cervicotomy in 2. None of the children initially treated with tonsillectomy or cervicotomy experienced a recurrence.

The PDNA type that corresponded to the highest proportion of recurrences was SA (33.0%), followed by PA (25%). Recurrences only occurred in patients with RPAs (16.6%), PTAs (13.6%) and LNAs (7.7%). There was no case of recurrence in patients with PPAs. We did not find evidence of any other type of complication.

A histopathological examination was ordered in 27 of the 64 patients that underwent surgical intervention, and its results did not result in changes to the treatment approach except in 2 cases (7.5%) where they guided the diagnosis of infection by atypical mycobacteria.

Samples of purulent material were used for culture in 19 of the 64 patients treated with surgery. There was no growth in 7 cases (37%). The microorganisms isolated most frequently were Staphylococcus aureus (15.8%) and acid-fast bacteria (10.5%).

Of all patients, 98.6% were discharged home with a prescription for oral antibiotics, most frequently amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (76.1%) or a cephalosporin (19.7%).

DiscussionOur study (whose sample corresponded to 100% of cases in the paediatric population of our province) revealed variability in the number of cases per year, which ranged from 2 to 11, and, consistently with other recent studies,1,2 an increase in the incidence in the past few years, with a mean of 3.8 cases per year in the first 8 years compared to 6 cases per year in the last 7 years.

In children, the diagnosis of deep neck abscesses may be complicated and requires an appropriate history taking and physical examination.10 The most indicative signs of PDNA (presence of a mass of limited range of movement in the neck) are not common, and in our study they were found in only 47% and 16% of cases, respectively. More frequent symptoms3,4 like fever (71%) or painful swallowing (55%) are less specific and may lead to misdiagnosis, as the clinical presentation may overlap with those of other diseases with a higher prevalence. Furthermore, our study found that the detection of cervical masses was more prevalent in abscesses in more superficial locations, such as LNAs, SAs and PAs, and less frequent in those in locations that were potentially more dangerous, such as PPAs and RPAs. We did not find cases with airway obstruction or stridor, as occurred in other studies,1,4 possibly due to the early diagnosis and treatment of the abscesses, which may have prevented progression to more advanced stages.

In agreement with similar studies,4,11 the most frequent types of PDNA by location were PTA, followed by LNA, PPA, RPA, SA and PA. When we analysed the distribution of these data by age, we found that in the 0–2 years age group, the most frequent type was SA, followed by LNA, while in children aged 3–6 years the most frequent types were LNA, RPA and PPA. The predominant type in children aged more than 7 years was PTA, amounting to 80% of PDNAs diagnosed in this age group, which means that more than 75% of all PDNAs that are not PTAs occur in children aged less than 7 years. Our data regarding the distribution of PDNA location by age group (P<.001) are consistent with the findings of most of the previous studies.1,4,12,13

The most frequently used imaging techniques were CT and sonography, employed in 86% of cases. Each was used under different circumstances: CT preferentially in deep abscesses and sonography in superficial abscesses. Computed tomography was used in the assessment of 100% of PPAs and 75% of RPAs. Sonography was used in 78% of SAs and 70% of LNAs, although in many cases it was the imaging test chosen for initial evaluation in order to avoid the unnecessary exposure of young children to radiation.14 Although CT requires the cooperation of the patient (and may require sedation) and exposes the child to radiation, we consider it the gold standard for assessment of PDNAs in a deep location, that respond poorly to treatment or in case complications are suspected; it is also the most useful technique for the purpose of surgical planning.3–5 Lateral neck radiographs, which are used frequently in emergency departments, were only performed in 8 cases, all of them of RPA, and our study found a marked decreasing trend in their use. On the other hand, in recent years there has been an increase in the use of MRI both for diagnostic purposes and for radiologic follow-up in cases where persistence of the PDNA is suspected after surgery, as this technique avoids the exposure of children to radiation.

Many authors advocate for conservative treatment of PDNA,6,7 while others call for surgical treatment only in case of respiratory compromise, clinical worsening or abscess size greater than 2cm.13,15 In our unit, consistently with the reports of other authors, we practice early surgical intervention in patients with abscesses greater than 2cm4,8 because we consider that this approach reduces the incidence of severe complications and recurrence.11 Thus, in our study, the treatment used in nearly 9 out of 10 cases of PDNA was surgical. Patients that did not undergo surgery all had LNAs with diameters of less than 1.4cm. This choice was based on previous studies whose authors estimated that an abscess section area greater than 2cm2 on CT correlated to the finding of purulent material during surgery.16 When the decision was made to perform surgery based on the size of the abscess or the depth of its location, surgery was always performed within 24h.

Still, the type of surgery varied. More superficial abscesses, such as LNAs or PAs, were treated with incision and drainage, with the exception of SAs which, while also being superficial, required a different approach in 3 cases (33%): in 1 case, cervicotomy due to the considerable size of the abscess, and in 2 cases that were initially treated with incision and drainage in which the aetiological agents were atypical mycobacteria, and in which regional lymphadenectomy was required after the results of the pathological examination and culture became available. Cases like these have already been described in similar studies, which report up a proportion of cervicotomy of up to 61% in the management of SAs. 17 In the case of PTAs, it is possible to treat the abscess with direct intraoral drainage (27% of cases), but this requires significant cooperation from the patient, which is why tonsillectomy under general anaesthesia was the selected approach in as many as 2 out of 3 cases in our sample. Abscesses in deeper locations, such as RPAs and PPAs, require more aggressive surgery. Specifically, in the PPA group 2/3 of abscesses were treated with tonsillectomy and 1/3 with cervicotomy, while most of the RPAs could be treated with drainage, although due to their depth this required general anaesthesia in every case.

In recent years, we have managed small-sized PDNAs with ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage18 with favourable outcomes and few complications, although we continue to prefer surgical drainage for larger abscesses.

The type of surgery was directly correlated with PDNA recurrence, of which there were 10 instances in 9 patients (one patient experienced 2 recurrences), amounting to a proportion of recurrence of 12.5% of all PDNAs. Other studies have reported similar proportions, ranging between 8% and 9%.4,11 The 10 cases of recurrence developed in patients treated with incision and drainage of the PDNA, and they were treated with a new incision and in 4 cases, tonsillectomy in 4 cases and cervicotomy in 2 cases. None of the patients treated with tonsillectomy or cervicotomy experienced a recurrence.

A histopathological examination was ordered in 27 of the 64 patients that underwent surgical intervention, and its results did not result in changes to the treatment approach except in 2 cases (7.5%) where they guided the diagnosis of infection by atypical mycobacteria, which led to a change in the type of surgery and subsequent medical treatment.

No pathogen grew in 37% of microbiological cultures, but it is important to take into account that nearly half of the patients were receiving oral antibiotherapy and all had received intravenous antibiotherapy before surgery, which could distort the results.4,10,19 The most frequent pathogen isolated was S. aureus, which diverged from the findings of other recent studies in which the most frequent pathogen was Streptococcus pyogenes,1,4,11 although it was also consistent with the results of other studies in the literature.20–22

The main strength of our study is its novel focus on the therapeutic approach to each of the different types of PDNA in relation to their location, the diagnostic tests used and the rate of recurrence associated with different surgical modalities. The limitations of the study are those characteristic of retrospective studies, especially when the follow-up period is long, as this is associated with a greater heterogeneity in trends, protocols and the decision-making of the involved clinicians. One example is the small number of samples obtained for microbiological testing, an issue that we have been addressing after its identification in this study. Another limitation was the small number of cases, which was due to the low incidence of PDNAs.

As for the implications of our findings for clinical practice and future research, our study highlights the need to reach a nationwide consensus for the management of PDNA, which ideally would involve a global effort with participation of the different hospitals that manage this condition to establish protocols for different locations in the neck, determining the imaging tests to be performed and the criteria to be applied to select the timing and type of surgical intervention.

ConclusionsThe results of this study may help adapt or update PDNA management protocols. Early tonsillectomy and/or cervicotomy for abscesses greater than 2cm or deep-space lesions were not associated with severe complications or abscess recurrence. We found a recurrence rate of 12.5% in association with less aggressive surgical approaches. The distribution of the different types of PDNA varied significantly between the established age groups. We recommend neck ultrasound as the main imaging test for evaluation of PDNAs with a superficial location and CT for evaluation of PDNAs in a deep location or for the purpose of surgical planning.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz de la Cuesta F, Cortes Castell E, Garcia Ruiz ME, Severa Ferrandiz G. Abscesos cervicales profundos infantiles: experiencia de una unidad de ORL infantil de referencia durante 15 años. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;91:30–36.