Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis (IPH) is a rare disease characterized by the classic triad of anemia, hemoptysis and bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, although it is not uncommon for the disease to manifest without the full constellation.1–3 The low incidence of the disease (0.24–1.23 cases per million children per year) and forms of disease presenting with one or two of these features in isolation may contribute to delays in diagnosis and treatment.4

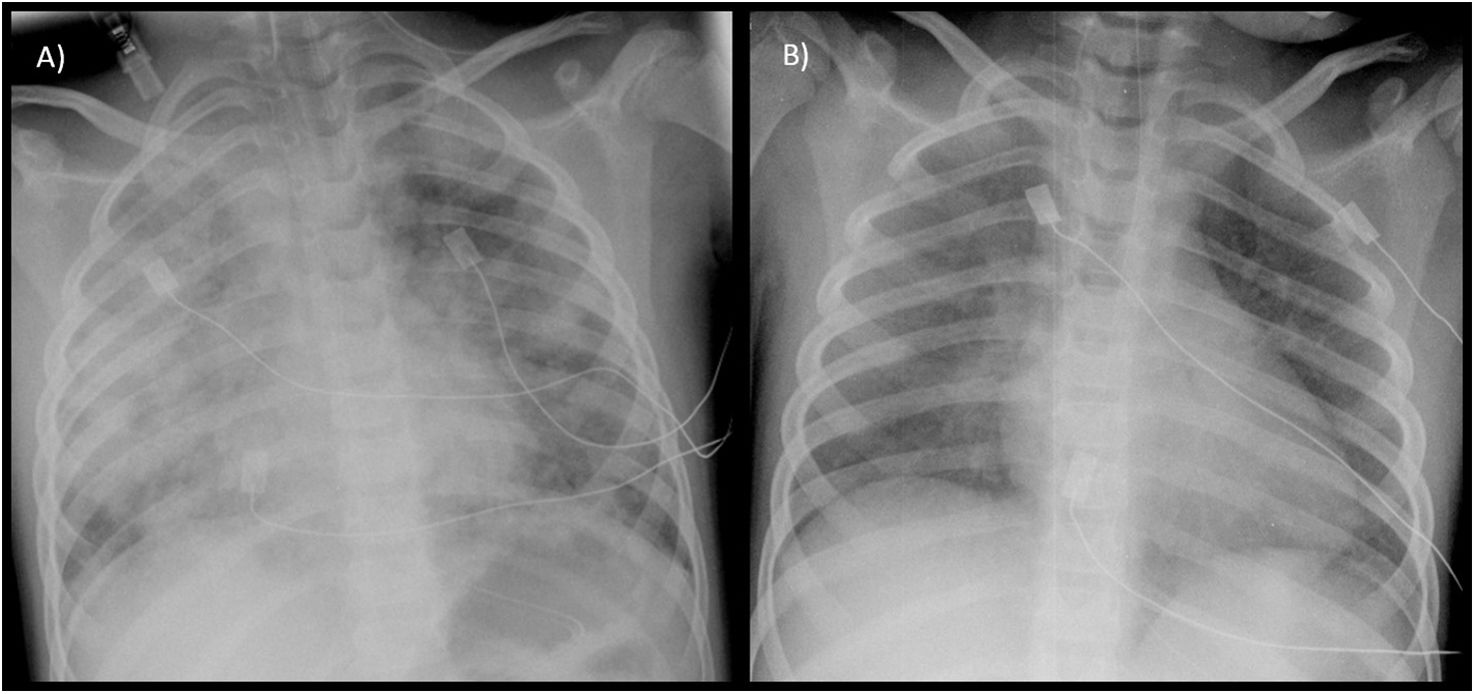

A female patient aged 5 years with a history of recurrent bilateral pneumonia presented with acute respiratory failure, bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and microcytic anemia (hemoglobin [Hb], 9.7 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume [MCV], 67 fL). She was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), where she underwent placement of a central jugular catheter, a urinary catheter and a size 5 tracheal tube for mechanical ventilation. The presence of blood in the secretions suctioned through the tracheal tube prompted performance of flexible bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), with a hemosiderin-laden macrophage percentage of 80% of in the cytological analysis. The patient was treated with intravenous steroids, which achieved resolution of symptoms and normalization of the chest radiography features within 48 h (Fig. 1). In the months following diagnosis, the management consisted of intravenous maintenance boluses of high-dose methylprednisolone, oral hydroxychloroquine and inhaled budesonide. Since the patient developed Perthes disease secondary to steroid therapy and experienced exacerbations upon attempting to taper or discontinue it, oral azathioprine was added on stopping steroid therapy, with a favorable response to date.

A female patient aged 5 years with an unremarkable history was admitted due to moderate hemoptysis (<200 mL blood/day) in absence of hypoxemia or respiratory distress. She presented with mild anemia (Hb, 10 g/dL; MCV, 76.9 fL) and evidence of infiltrates in the right upper and lower lobes on the chest radiograph. The flexible bronchoscopy allowed visualization of profuse active bleeding in the right upper lobe, with 65% of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in the BAL specimen. She received intravenous steroid therapy during the acute phase, which achieved a favorable clinical response. Subsequent management consisted of administration of high-dose methylprednisolone boluses for one year in addition to oral hydroxychloroquine and inhaled budesonide maintained to date, and the patient has not experienced recurrences in the 8 years following the diagnosis.

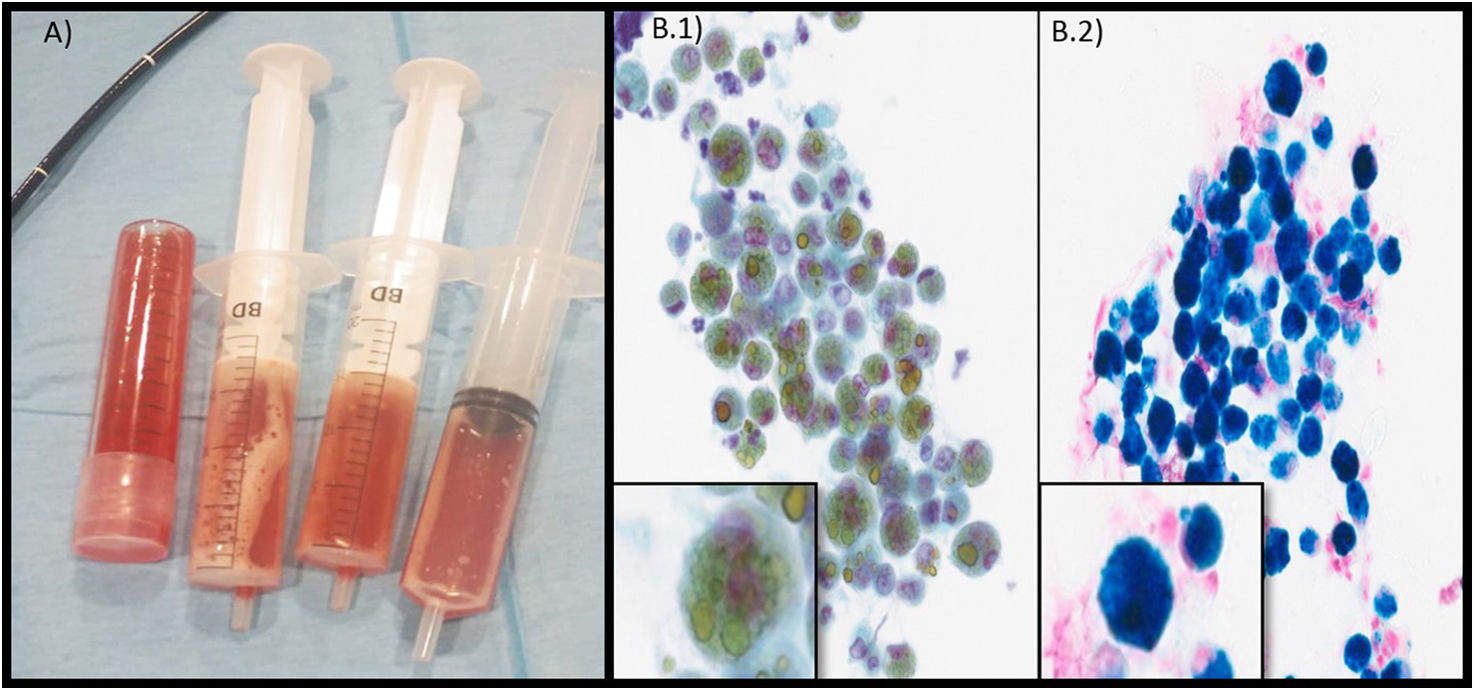

A female patient aged 3 years, who was of Pakistani descent and with a significant language barrier between the family and the care team, was admitted to the PICU due to tachycardia, hypotension, a capillary refill time of 3 s, tachypnea and general malaise as well as severe microcytic anemia (Hb, 2.3 g/dL; MCV, 44.4 fL) and bilateral pulmonary infiltrates with diffuse B-lines on the lung ultrasound scan (interpreted as acute pulmonary edema resulting from heart failure secondary to anemia). Due to the presence of chronic iron-deficiency anemia (ferritin, 20.8 ng/mL; transferrin saturation, 1.95%), she was treated with red blood cell transfusion and oral iron supplementation (1.5 mg/kg/day), which allowed her to be discharged home 5 days after admission (stay in PICU, 48 h). She required readmission 6 months later due to recurrence of anemia (Hb, 5.9 g/dL) and asthenia. Blood-stained vomit and pulmonary infiltration were detected during the gastroscopy performed to ruled out gastrointestinal bleeding. At this time, the family reported occasional hemoptysis not preceded by productive cough. Suspicion of alveolar hemorrhage prompted performance of flexible bronchoscopy, with recovery of bloody fluid in the BAL with 90% of hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Fig. 2). The patient received intravenous boluses of high-dose methylprednisolone for 20 months and is currently in treatment with oral hydroxychloroquine and inhaled budesonide, with a favorable outcome.

(A) Image of fluid specimens collected by means of bronchoalveolar lavage (three syringes) and bronchial aspiration (tube). (B) (1) and (2) Cytopathological examination (×40) of bronchoalveolar lavage specimen with visualization of hemosiderin-laden macrophages. (1) Macrophages with inner structures stained golden (hemosiderin). (2) Perls stain with visualization of macrophages (iron in hemosiderin stained blue).

Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis should be suspected in the presence of the classic triad, although the complete triad is only present in 50% of affected pediatric patients.2 A predominance of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in BAL or gastric aspirate samples is characteristic of IDH.4 Other causes of alveolar hemorrhage need to be ruled out, such as cardiovascular or rheumatic diseases or other triggers (cow’s milk protein allergy or celiac disease),5 as illustrated by the three cases we have presented. Although lung biopsy allows a definitive diagnosis, its practice is currently under debate.6 Treatment in the acute phase is based on systemic steroids, and subsequent maintenance therapy on oral steroids or intravenous steroid therapy delivered in high-dose boluses (methylprednisolone at 20−30 mg/kg/day/3 consecutive days a month), for an average duration of 12–18 months. Other immunosuppressant agents have been used to prevent recurrence and reduce the dose of systemic steroids, such as hydroxychloroquine (6.5 mg/kg/day), azathioprine (2 mg/kg/day) and inhaled steroids.4 In presenting these three cases, we want to highlight the challenges posed by the diagnosis of this disease, as each patient had onset with a different presentation (recurrent pulmonary infiltrates initially interpreted as pneumonia; hemoptysis; severe anemia), which may delay initiation of steroid therapy.