Evidence-based medicine provides a structured and practical approach for addressing the challenges of modern medicine, which is characterized by an overload of information and the need for well-founded clinical decision-making. This method consists of five steps: formulating clear structured clinical questions, conducting efficient literature searches, critically appraising the evidence, evaluating its applicability and, finally, integrating the resulting knowledge into clinical practice. The first step involves creating structured questions that address specific clinical needs, often using the widely known PICO framework developed by the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in Oxford. Subsequently, to avoid information overload, it is essential to manage the abundance of data by prioritizing high-quality sources and adopting strategies that can yield quick and reliable answers. The core of evidence-based medicine lies in critical appraisal, whereby the validity, importance, and applicability of studies are assessed. This process helps avoid the mistake of accepting conclusions without questioning them. The final steps emphasize integrating evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences, highlighting that, without proper implementation, evidence-based medicine can remain a theoretical framework without practical impact. In demanding clinical settings, evidence-based medicine aims to balance care quality, efficiency, and resource management, supporting professionals in making optimal, evidence-based decisions to improve health care.

La Medicina Basada en la Evidencia ofrece un enfoque estructurado y práctico para enfrentar los desafíos de la medicina moderna, marcada por un exceso de información y la necesidad de decisiones clínicas fundamentadas. Este método consta de cinco pasos: formular preguntas clínicas estructurada claras, realizar búsquedas bibliográficas eficientes, valorar críticamente la evidencia, evaluar su aplicabilidad y, finalmente, integrar el conocimiento en la práctica clínica. El primer paso consiste en elaborar preguntas estructuradas que aborden necesidades clínicas específicas, proponiéndose el sistema popularmente conocido como PICO, elaborado por Centro de Medicina Basada en la Evidencia de Oxford. Posteriormente, y para no caer en la infoxicación, es esencial gestionar la sobrecarga de información, priorizándose fuentes de alta calidad y adoptando estrategias que permitan encontrar respuestas rápidas y confiables. El eje central de la Medicina Basada en la Evidencia es la lectura crítica, donde se analiza la validez, importancia y aplicabilidad de los estudios. Este proceso ayuda a evitar el error de aceptar conclusiones sin cuestionarlas. Los últimos pasos enfatizan la integración de la evidencia con la experiencia clínica y las preferencias del paciente, destacando que, sin una implementación adecuada, la Medicina Basada en la Evidencia corre el riesgo de quedar como un marco teórico vacío. En un entorno clínico exigente, la Medicina Basada en la Evidencia busca equilibrar calidad asistencial, eficacia y gestión de recursos, ayudando a los profesionales a tomar decisiones óptimas y basadas en evidencia para mejorar la atención sanitaria.

Scientific research drives the advancement of knowledge by questioning unfounded beliefs and establishing solid foundations for understanding phenomena. Born out of curiosity, it requires clear hypotheses, specific objectives, reproducible methodologies and precise tools to corroborate or refute accepted theories. In medicine, scientific knowledge guides the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of patients in addition to health promotion and disease prevention strategies. Without this foundation, medical practice is unmoored from evidence, losing its scientific nature. Clinicians must integrate science, experience and evidence to practice medicine based on the scientific method. In this context, evidence-based medicine (EBM) emerges as a means to better address the challenges of modern medicine, including the existence of a vast and constantly evolving body of scientific information, the duty to offer highest possible quality of care and the limited amount of health care resources. Evidence-based medicine not only seeks to guarantee the best possible quality of care, but also constitutes an ethical imperative, as it helps prevent clinical decisions demonstrated to not be the most appropriate and that can have a deleterious effect on patient health outcomes. To this end, a systematic method has been proposed to address the uncertainties that arise in everyday clinical practice through five essential structured steps. In the words of William Osler,1 “medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability”, and training in EBM, to be sure, is a helpful way to take on its challenges.2–4

First step: ask good questionsThe formulation of clinical questions should be considered one of the many techniques that clinicians need to integrate in their everyday clinical practice. It is a constructive way to handle the uncertainty that health care professionals face on a daily basis. The first step in EBM is to turn this need for information into a clinical question. Questions arise for two reasons: because we have ongoing doubts in our practice (which requires, at the very least, acknowledging ignorance, questioning what is new, and questioning what is routine) and because we need answers (as we frequently face clinical practices characterized by unwarranted variability and decisions that do not always align with the best available evidence).5,6

Types of questionsIt is important to differentiate between the types of questions we can ask as a preliminary step to the development of a structured clinical question. The complexity of clinical questions tends to be associated with the level of professional experience, although this trend is not always linear. Thus, a first-year medical resident will first need to acquire large amounts of knowledge regarding the general or basic aspects of certain diseases. Therefore, most of the questions asked will be general or “background” questions and will have two fundamental components: the root of the question (who, what, where, when, how, etc.) accompanied by a verb; and the disorder or an aspect of it. An example of this type of question would be: What is the most common etiological agent of bacterial pneumonia in children? In other instances, however, our uncertainty will be deeper and may affect the decision-making process in a specific patient. This type of uncertainty gives rise to questions about specific aspects of a particular disease or health problem. Questions of this nature are known as “foreground questions” and are most suitable for answering with an EBM approach.

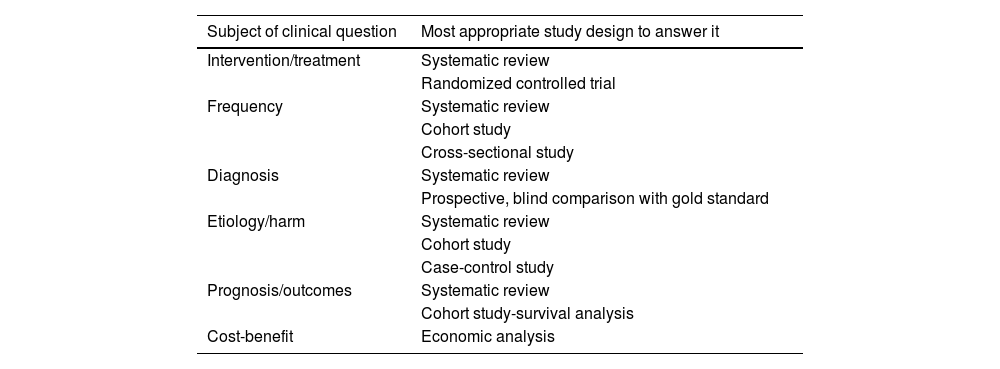

Identifying the type of clinical question: the key to a well-built questionBefore structuring a clinical question, it is important to identify the type of information we are seeking: is it a question about diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, prevention, or etiology? Clearly formulating a clinical question also helps clinicians identify the type of study design that is most likely to answer it, as can be seen in Table 1.

Determining the study design that is most appropriate for answering each type of clinical question.

| Subject of clinical question | Most appropriate study design to answer it |

|---|---|

| Intervention/treatment | Systematic review |

| Randomized controlled trial | |

| Frequency | Systematic review |

| Cohort study | |

| Cross-sectional study | |

| Diagnosis | Systematic review |

| Prospective, blind comparison with gold standard | |

| Etiology/harm | Systematic review |

| Cohort study | |

| Case-control study | |

| Prognosis/outcomes | Systematic review |

| Cohort study-survival analysis | |

| Cost-benefit | Economic analysis |

Structuring a specific clinical question requires its dissection into four (or sometimes five) distinct parts:

- •

P. the patient or problem of interest.

- •

I/E. main intervention or exposure (which, depending on the aspect of clinical practice being investigated, could be a treatment, diagnostic test, prognostic factor etc)

- •

C. Comparison of the intervention or exposure (when pertinent, as in some instances clinical questions are formulated that do not require any comparison).

- •

O. outcome of interest.

- •

T. Time may be fifth an element in the question, and it is optional.

These are the elements that constitute a structured clinical question, the first (key) step in the EBM approach and in any systematic review, research project or clinical practice guideline.

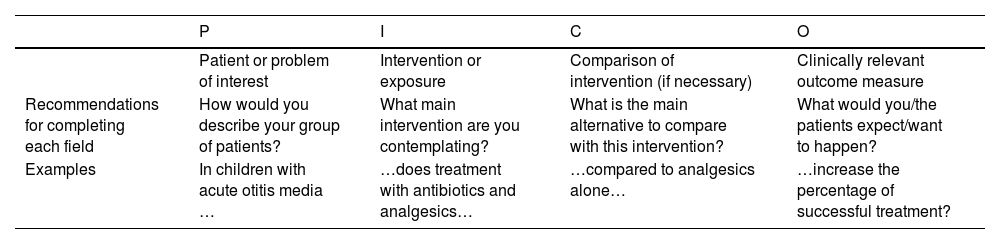

The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine proposed the framework generally known as PICO, for the acronym of Patient or Problem, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome, which may also be found in the expanded form, PICOT (which includes exposure as an alternative to intervention and adds the element of Time) or in the abbreviated form of PIO (as these are the actual three key elements of the question). Table 2 gives recommendations to complete each part of a structured clinical question and provides one example.

Component of a structured clinical question.

| P | I | C | O | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient or problem of interest | Intervention or exposure | Comparison of intervention (if necessary) | Clinically relevant outcome measure | |

| Recommendations for completing each field | How would you describe your group of patients? | What main intervention are you contemplating? | What is the main alternative to compare with this intervention? | What would you/the patients expect/want to happen? |

| Examples | In children with acute otitis media … | …does treatment with antibiotics and analgesics… | …compared to analgesics alone… | …increase the percentage of successful treatment? |

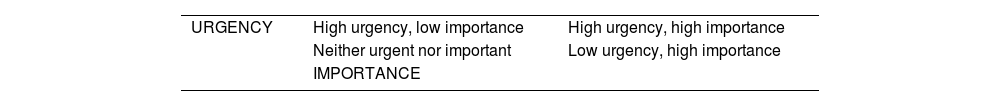

Well-built clinical questions are useful for the purpose of defining gaps in knowledge more precisely and establishing a more efficient literature search strategy; when they are answered effectively, they provide a positive reinforcement to professionals, serving as the stimulus for identifying additional knowledge gaps and formulating new questions. However, there are challenges intrinsic to the question itself that may hinder its appropriate formulation. For this reason, various suggestions have been proposed to help decide which question should be answered first:

- •

Which question is most important for the wellbeing of the patient? This should be determined according to the urgency of the health problem and its importance, as shown in Table 3, criteria that should help decide which question should be prioritized at each point.

- •

Which question is most feasible to answer within available time?

- •

Which question is most likely to recur in daily clinical practice?

- •

Which question is more important for the needs of our students or our patients?

Applying all of the above, it should be possible to formulate a well-built clinical question, which is a key milestone to proceed on to the next step.

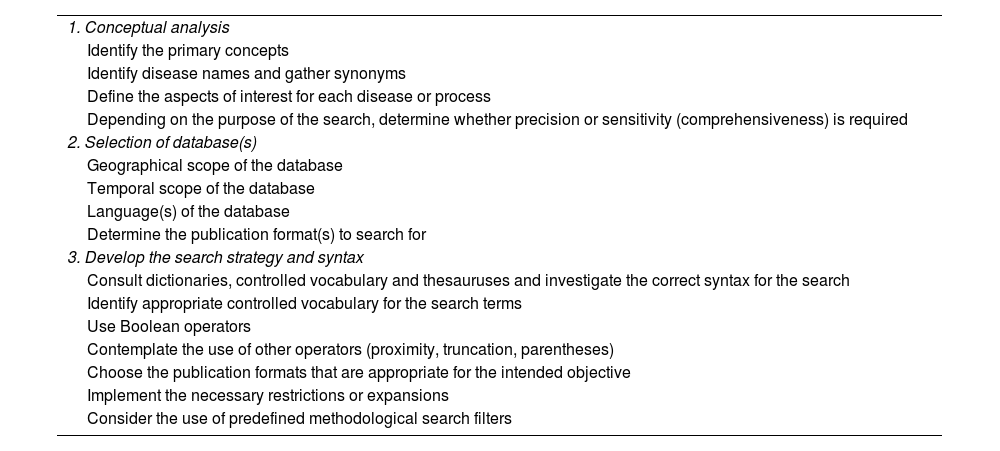

Second step: conducting an efficient search without drowning in infoxicationOur current challenge in the face of “infoxication” is not to generate more information but rather to produce relevant responses that facilitate clinical decision-making in specific scenarios involving our patients. To move from information to knowledge and from knowledge to action, we must screen the information that is available, obtained from searches, considered valid, important, and applicable and then selected, to eventually only keep the information that is useful. To perform literature searches in databases successfully, it is essential to take into account certain methodological aspects and to try to follow the steps described in Table 4.

Summary of the stages of a literature search.

| 1. Conceptual analysis |

| Identify the primary concepts |

| Identify disease names and gather synonyms |

| Define the aspects of interest for each disease or process |

| Depending on the purpose of the search, determine whether precision or sensitivity (comprehensiveness) is required |

| 2. Selection of database(s) |

| Geographical scope of the database |

| Temporal scope of the database |

| Language(s) of the database |

| Determine the publication format(s) to search for |

| 3. Develop the search strategy and syntax |

| Consult dictionaries, controlled vocabulary and thesauruses and investigate the correct syntax for the search |

| Identify appropriate controlled vocabulary for the search terms |

| Use Boolean operators |

| Contemplate the use of other operators (proximity, truncation, parentheses) |

| Choose the publication formats that are appropriate for the intended objective |

| Implement the necessary restrictions or expansions |

| Consider the use of predefined methodological search filters |

In the age of “globalization,” the Internet and search engines provide users with a wealth of information, but using these means to search for sources returns an enormous amount of information of varying quality without any form of screening. Google is often the search engine of choice for patients, but it should not be the primary search tool for health care professionals. Although it can facilitate access to reliable sites, such as those of scientific societies or official institutions, it does not guarantee systematic or filtered retrieval of evidence.

From this general stance, the Working Group on Evidence-Based Pediatrics proposes a step-by-step search strategy, bearing in mind one premise: there is no such thing as an ideal or universal search for literature sources.

- •

First stage: Start with tertiary sources, mainly EBM metasearch engines (eg, Trip medical database). The Trip search engine yields color-coded results. The best information appears in green: systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines, and evidence-based synopses. The Trip interface has been modified recently and now allows users to structure their searches based on PICO criteria. The purpose is to assess whether the answer can be found in systematic reviews or meta-analyses (mainly through the Cochrane Collaboration), clinical practice guidelines (mainly through the National Guidelines Clearinghouse and GuíaSalud) and health technology assessment reports (chiefly through the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment [INAHTA]). If the answer cannot be found in sources of this quality, it is always possible to continue searching for a less definitive answer in other secondary sources that are less reliable: secondary journals and critically appraised topics.

- •

Second stage: Continue with secondary sources or databases. Medline, which can be accessed free of charge through PubMed, is a key source due to its broad subject coverage, rigorous indexing, and reliability as a basis for structured scientific searches. Given the complementary nature of bibliographic databases, we recommend performance of additional searches in, at minimum, Embase (not free) and databases in Spanish. A detailed explanation of how to do this can be found in the open access references.7

- •

Third stage: If the answer has not been found in the previous steps, the next step is to search traditional primary sources. Searching for information in biomedical journals that are not indexed in the previous databases and in textbooks is always an option, in addition to backward reference searching.

- •

Fourth stage: as a last resort, a “wild” search can be performed using web browsers (what is known as “googling”) for valid and relevant information that is not dumped to any databases, such as documents from the Ministry of Health, scientific societies, scientific meetings etc.

Although all five steps of EBM are important (ask, acquire, appraise, apply, assess), the key element at its core is the critical appraisal of scientific sources, which involves judging whether the evidence is valid (scientific rigor), important (relevance in clinical practice) and applicable (in the specific care setting). As the title of this section summarizes, the reader has to choose between being a critical consumer of scientific content (appraising) or simply settling on believing what is read, focusing on the impact factor or reputation of the journal rather than the content and methodology of the article.

To this end, EBM offers a structured thinking and working approach that has evolved from the methods for critical appraisal and problem-based learning proposed by the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group8 of McMaster University (Canada) starting 30 years ago, subsequently developed and presented in a book and a series of 34 articles published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) between 1993 and 2000.

This is a crucial step, one requiring considerable effort and whose results on its learning and application will only become evident in the medium to long term, but without which EBM would lack rigor. The reader of scientific literature has to determine whether the presented evidence is valid (applied appropriate methodology), important or relevant, and applicable to real-world clinical practice.9

A correct approach to critical appraisal entails an understanding of the essence of EBM, which, from its initial conception, is at the service of clinical decision-making, going beyond the numbers and statistical methods that, at times, keep the reader from delving into it. Let us present an example of what we mean by this:

In 2003, Kato et al.10 published the results of a study conducted to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the Helicobacter pylori stool antigen test (HpSA), an enzyme immunoassay technique. It was a prospective multicenter study conducted in Japan in a sample of 264 children in whom the HpSA was performed using 13C-urea breath test (UBT) as the gold standard for comparison. Of the 264 children, 120 had gastrointestinal symptoms (gastritis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, recurrent abdominal pain) and the remaining 144 were asymptomatic. The HpSA exhibited a sensitivity of 96.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 90.8%–99.7%), a specificity of 96.3% (95% CI, 93.6%–99%), a positive likelihood ratio of 25.9 and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.04. The authors concluded that the HpSA was an accurate test for the detection of H pylori infection in children of any age.

At this point, the reader has to choose whether to appraise the evidence or simply believe it. First, it should be noted that the method chosen for reference is not the most valid, as the gold standard would be the gastric tissue biopsy and histological examination (as it would not only allow detection of the pathogen but also assessment of gastric involvement). The HpSA exhibited an acceptable accuracy in relation to the UBT results (positive likelihood ratio > 10 and negative likelihood ratio < 0.1). Given that the prevalence of H pylori infection in children with suggestive symptoms is approximately 12%, the probability of having the infection would increase to 78% (95% CI, 72%–83%) in HpSA-positive patients and decrease to 1% (95% CI, 0%–1%) in HpSA-negative patients. Based on this information, if the test is negative, we can practically rule out H pylori infection. However, if the test is positive, although it is highly likely that the patient has an infection, the clinical presentation will determine whether an endoscopy with biopsy, a urea breath test or a test-and-treat approach is indicated. If only the results are taken into account, rather than interpreting them in the context of the patient and clinical experience, the test may end up being used inappropriately, which could lead to diagnosis H pylori infections that are unrelated to the presenting complaint (15.8% of asymptomatic children have H pylori in their stools in our care setting), resulting in medicalization and potential iatrogenic effects, in addition to diverging considerably from current recommendations for the management of H pylori infection.11 This is a clear example of how the assessment of the clinical relevance of a study may lead clinicians to change their practices, independently of whether the study is methodologically sound.

A more detailed analysis of this core element of EBM has been published as a monograph.12

Fourth and fifth steps: avoiding swimming only to perish in the shores of health care variabilityAfter confirming that the best external evidence found in the literature is valid (from a scientific point of view) and important (from a clinical point of view), we face the decisive question and ultimate goal of EBM: can the resulting evidence be integrated into our clinical expertise and the preferences of patients/users and applied in the management of our patients? Having answered the question of applicability, which brings the critical appraisal of scientific publications to an end (as explained in the past section) and constitutes the fourth step in EBM, one more step remains, an integral one, which is assessing the performance of the application of scientific evidence to clinical practice,13,14 or, in other words, whether diagnostic or therapeutic decisions are appropriate based on the current evidence.

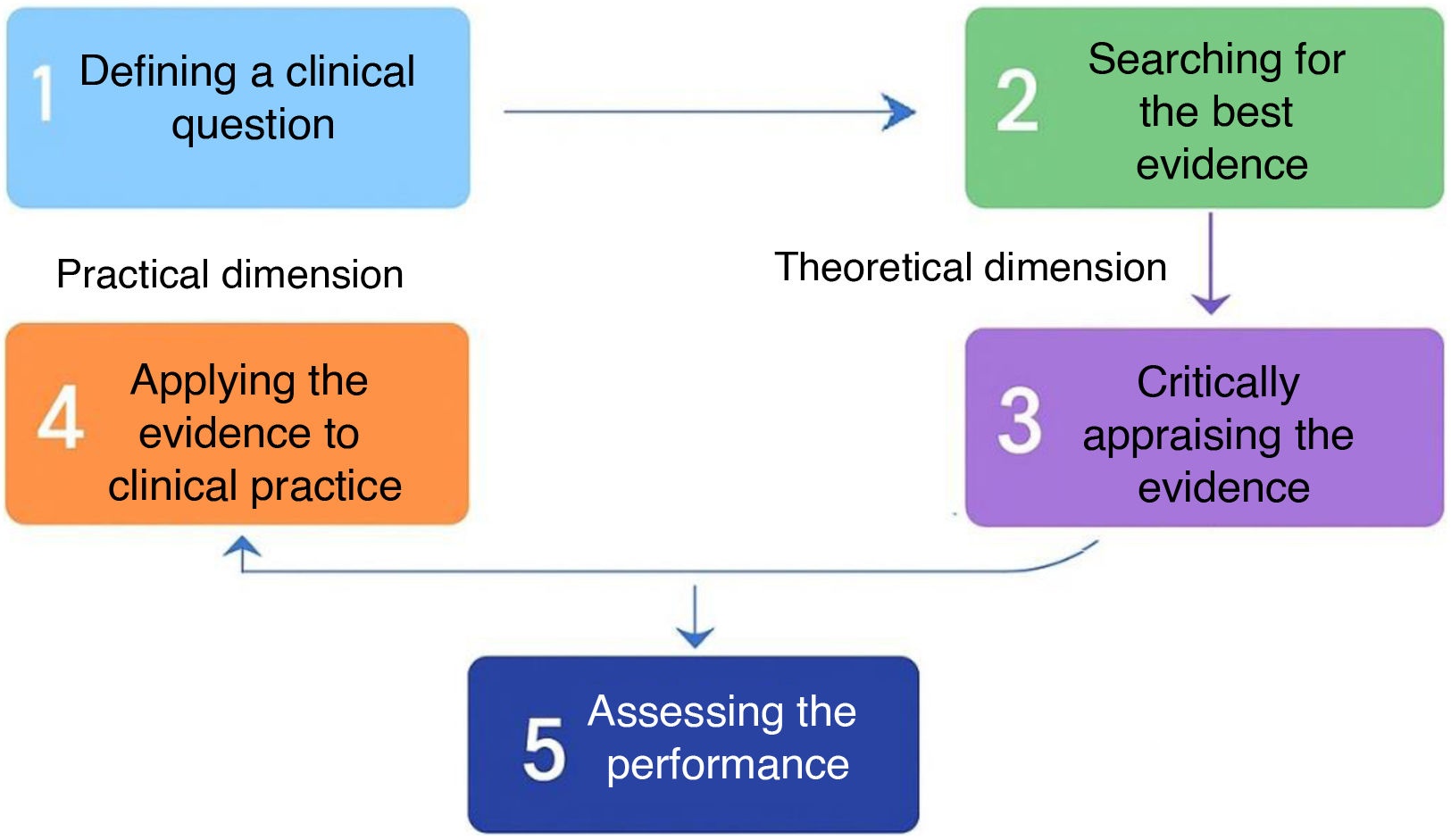

Fig. 1 presents the relationship of the different steps of the EBM, theoretical as well as practical. At the theoretical level, EBM requires a minimum basic knowledge in bibliometrics and literature searches (step 2) as well as epidemiology and biostatistics (step 3). Still, the ultimate goal of EBM is essentially practical: a clinical problem is approached through a structured question (step 1), and the process ends with the application of the evidence (step 4). The assessment of the outcomes of applying the evidence to clinical practice (step 5) is the final integrative step.15–17

One of the key questions to ask in terms of applicability is whether the differences between our patients and the patients in the study are too significant for the results to be useful. Additional aspects that need to be assessed vary depending on the objective of the study (treatment, diagnosis, harmful effects, prognosis/outcomes, etc), always considering the benefits-harms-costs triangle of conscientious health care delivery and the influence of potential conflicts of interest arising from the interactions of patients, physicians and the pharmaceutical industry. These influences may affect not only the prescribing of certain treatments, but also the generation and dissemination of biomedical knowledge, including clinical practice guidelines. Therefore, it is essential that health care professionals have the capacity to recognize conflicts of interest in the scientific literature and critically appraise the independence of the consulted sources. Transparency and a critical and informed approach are key to minimize these risks and ensure the practice of medicine based on the best available evidence.

Still, it is usually this last step that poses the greatest challenge: getting evidence is not enough, but it needs to be put into practice, or else the EBM approach turns into a fruitless theoretical framework. The reason is that health care professionals in general and pediatricians in particular face the challenge of providing high-quality care in an ever-changing context, where therapeutic, diagnostic, and prognostic options increase by the day and the expectations of patients (and their families) keep rising. At the same time, we are under significant pressure to limit the use of resources and control their management. In this complex scenario, a question arises: are we making the best possible clinical decisions? And, above all, are we adapting our clinical practice to the available scientific evidence?

Providing high-quality care to our patients under working conditions that are not always ideal constitutes a challenge for all health care professionals. If we want to make the best possible clinical decisions and choose the most appropriate diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive procedures in each clinical scenario, we must combine our knowledge and expertise with the best available evidence. However, if we make a critical assessment of our practice, we can see how a significant proportion of our decisions are not always based on valid scientific evidence. Some clear examples in pediatric care are the unnecessary use of antibiotics or the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for management of respiratory infections, noncompliance with preventive measures (vaccinations, vitamin supplements), insufficient treatment for asthma control, the approach to the diagnosis and treatment of bronchiolitis, febrile seizures or fever without source in infants, the incorrect or insufficient use of diagnostic tests in urinary tract infections and the indication of tonsillectomies.

The appropriateness of health care should be one of the core tenets in the education of health care professionals. Care quality in real-world clinical practice depends on its appropriateness, which involves finding the balance between potential benefits, associated risks and cost of health care practices. The assessment and optimization of appropriateness requires understanding the key concepts associated with this aspect and subsequently seeking support at the institutional and professional levels.18

Evidence-based medicine meets artificial intelligenceEvidence-based medicine has been developing for a long time and evolved significantly, establishing itself as an essential tool in contemporary clinical practice. The goal of the Working Group on Evidence-Based Pediatrics has always been to offer health care professionals the knowledge and tools required to make informed clinical decisions based on the best available scientific evidence

As EBM continues to evolve, new tools have emerged that may facilitate, even accelerate, several of its fundamental steps. In particular, artificial intelligence-based systems are transforming the way health care professionals access, filter, and synthesize scientific information. Tools such as Perplexity, Elicit, Consensus, and the Deep Research feature of some chatbots (such as ChatGPT) allow users to perform natural language searches, generate automatic summaries, analyze articles and obtain answers based on scientific consensus, all in significantly less time and through an intuitive conversational user interface. However, these tools are not a substitute for conventional databases such as PubMed, which continue to be the gold standard for finding robust and specific evidence, although they can effectively complement literature searches, especially in the early stages of the process or to get a quick overview. In high-pressure clinical settings, where there is little time to conduct structured searches, these systems can offer preliminary information that must then be critically appraised. Thus, far from being a threat to methodological rigor, artificial intelligence is emerging as an ally in navigating the current overload of information more efficiently.

The issue is not whether these tools should be incorporated into EBM, but how to do it judiciously. To avoid bias, errors or hasty conclusions, clinicians need to be trained in the proper use of these technologies, and a critical attitude needs to be fostered to ensure that the obtained results are always appraised taking into account the scientific evidence, professional experience and patient needs. Twenty-first century EBM cannot turn its back on artificial intelligence, but should rather integrate it as a strategic tool that can help us to continue asking good questions, seeking relevant answers, and, above all, improving clinical decision-making.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

M. Salomé Albi Rodríguez, Pilar Aizpurua Galdeano, María Aparicio Rodrigo, Nieves Balado Insunza, Albert Balaguer Santamaría, Fernando Carvajal Encina, Eduardo Cuestas Montañes, M. Jesús Esparza Olcina, Sergio Flores Villar, Garazi Frailea Astorga, M. Victoria Martínez Rubio, Manuel Molina Arias, Eduardo Ortega Páez, Begoña Pérez-Moneo Agapito, M. José Rivero Martín, Álvaro Gimeno Díaz de Atauri, Laura Cabrera Morente, Elena Pérez González, Juan Ruiz-Canela Cáceres.