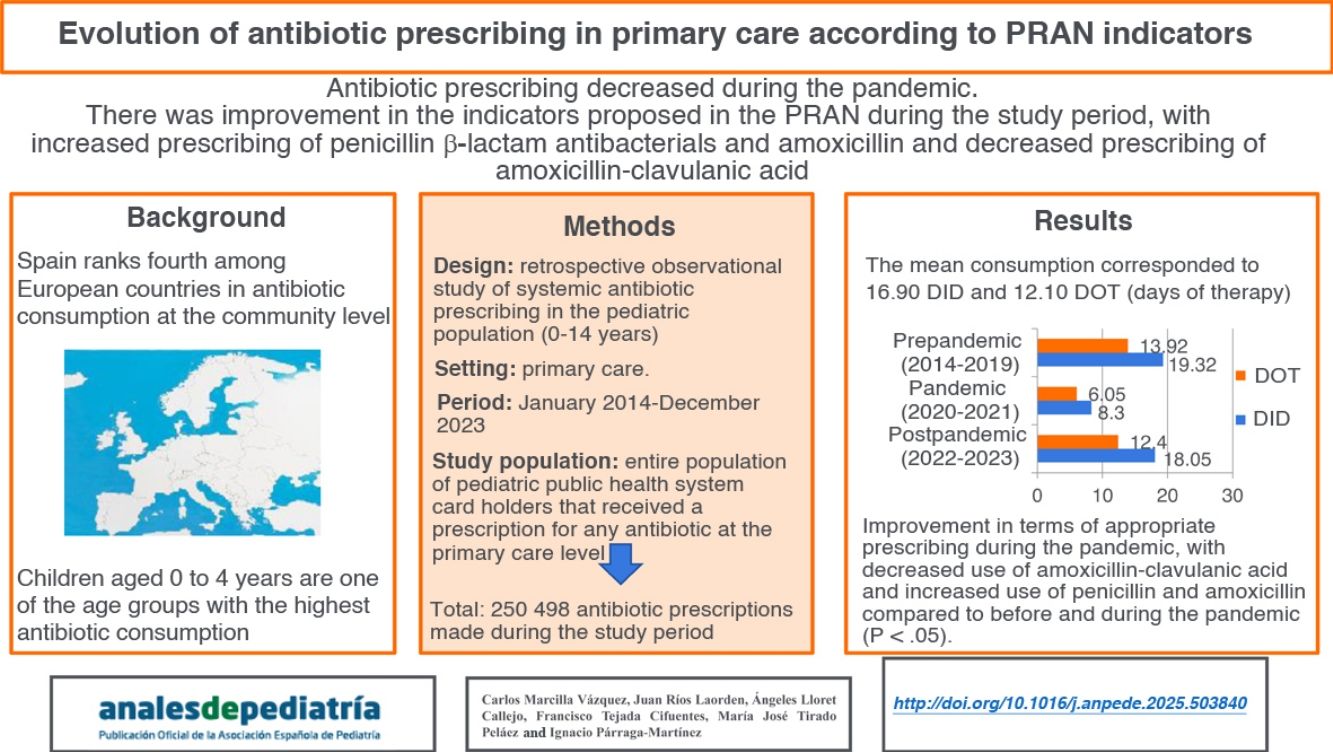

Spain is the fourth European country with the highest antibiotic consumption at the community level, being children aged 0-4 years one of the age groups with the highest amount of consumption. The aim of this study was to analyze the evolution of antibiotic prescription of the pediatric population in a Primary Health Care area according to the indicators of the Spanish Action Plan on Antibiotic Resistance (PRAN) in a period of ten years (2014-2023), as well as to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by the comparison between 2020-2021 years and a previous (2014-2019) and a later periods of time (2022-2023).

Material and methodsRetrospective observational study of the prescription of antibiotics for systemic use (J01 group of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification) in pediatric patients (0-14 years) belonging to the Primary Health Care area of the Gerencia de Atención Integrada (GAI) de Albacete between 2014 and 2023.

ResultsMean antibiotic prescription was 16.90 defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day (DID) and 12.10 DOT (days of therapy). Pre-pandemic data (2014-2019) was 19.32 DID and 13.92 DOT, being reduced during the two years of the pandemic (2020-2021) to 8.30 DID and 6.05 DOT and subsequently increased to 18.05 DID and 12.40 DOT in post-pandemic years (2022-2023). An improvement in the adequacy of antibiotic prescription was observed after the COVID-19 pandemic, with a reduction of the consumption of amoxicillin-clavulanate and a greater consumption of penicillin and amoxicillin during pre-pandemic and pandemic years (p < 0.05).

ConclusionsThoughout the period of years analysed, an improvement in the consumption indicators proposed by the PRAN, with a higher use of beta-lactamase sensitive penicillins and amoxicillin and a reduced consumption of amoxicillin-clavulanate.

España es el cuarto país europeo con mayor consumo de antibióticos a nivel comunitario, siendo los niños de 0-4 años uno de los rangos de edad de mayor consumo. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar la evolución de la prescripción de antibióticos en la población pediátrica de Atención Primaria de un área Sanitaria en función de los indicadores del PRAN durante diez años (2014-2023), así como, evaluar el impacto de la pandemia de COVID-19 comparando el periodo 2020-2021 respecto al previo (2014-2019) y posterior (2022-2023).

Material y métodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo de prescripción de antibióticos sistémicos (grupo J01, clasificación Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification) en población pediátrica (0-14 años) en el ámbito de Atención Primaria de la Gerencia de Atención Integrada (GAI) de Albacete entre 2014 y 2023.

ResultadosLa prescripción media de antibacterianos fue de 16,90 dosis diaria definida por 1000 habitantes/día (DHD) y 12,10 DOT (days of therapy). Los datos prepandemia (2014-2019) fueron de 19,32 DHD y 13,92 DOT, reduciéndose durante la pandemia (2020-2021) hasta 8,30 DHD y 6,05 DOT y aumentando, posteriormente (2022-2023), hasta 18,05 DHD y 12,40 DOT. Se observó una mejora en la adecuación de la prescripción tras la pandemia, con menor utilización de amoxicilina/clavulánico y mayor de penicilina y amoxicilina que antes y durante pandemia (p < 0,05).

ConclusionesA lo largo del periodo estudiado se observó una mejoría de los indicadores de consumo propuestos por el PRAN, mostrando mayor uso de penicilinas sensibles a betalactamasas y de amoxicilina, y menor consumo de amoxicilina/clavulánico.

Antibiotics are among the 10 most used groups of pharmaceuticals in pediatric care, and children aged 0 to 4 years, in addition to the population aged > 75 years, are the age groups with the highest antibiotic consumption.1,2 More than 90% of antibiotic consumption originates in the primary care (PC) system, although it is estimated that nearly half of the prescriptions are unnecessary or inappropriate.3,4 In addition, according to the most recent report of the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption Network (ESAC-Net), published in 2024, Spain is the fourth leading country in antibiotic consumption at the community level.5

The use of antibiotics contributes to the development of antimicrobial resistance, which is currently one of the greatest public health challenges.6,7 In the past few years, with the aim of monitoring antibiotic consumption and controlling bacterial antimicrobial resistance, several strategies have been launched by organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) in the United States, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) or the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC) in Europe and, in Spain, the National Plan Against Antibiotic Resistance (PRAN, Plan Nacional Frente a la Resistencia a los Antibióticos).5,8 While none of these institutions collects data in the pediatric population, there are some studies that offer pediatric data for Spain.4,9–13

Due to the high antibiotic consumption in the pediatric population, in 2017 the PRAN established high-priority improvement goals for PC pediatrics.14 The latest update of the PRAN, from 2022, emphasizes the need to implement antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) at both the hospital and community levels.15

The advent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the measures implemented to control it16 changed health care services and affected the prescribing and consumption of antibiotics, with a decrease in antibiotic prescriptions during the pandemic.17–21

The aim of our study was to analyze longitudinal trends in antibiotic prescription over a 10-year period (2014-2023) in the pediatric population of a PC catchment, area using the PRAN indicators as reference, and to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, comparing the pandemic period (2020-2021) with the prepandemic (2014-2019) and postpandemic (2022-2023) periods.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective observational study of the prescription of antibacterials for systemic use (group J01 of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] classification) in the pediatric catchment population (aged 0-14 years, both included) of the PC system of the Integrated Health Care Administration (IHCA) of Albacete, Spain, between 2014 and 2023. We excluded prescriptions for antibacterials not for systemic use and for anti-infective drugs other than antibacterials, such as antimycotics (group J02), antimycobacterials (J04) and antivirals (J05). We analyzed antibiotic prescriptions for pediatric patients holding an Albacete public health system card issued from pediatric care, family medicine and urgent care clinics of the public primary care system from January 2014 to December 2023.

The data were obtained through the Technical Services of the primary care electronic health record system (Turriano) of the Department of Health of Castilla-La Mancha (SESCAM), coded and anonymized. We excluded prescriptions made in hospitals, the private health care system or private practices.

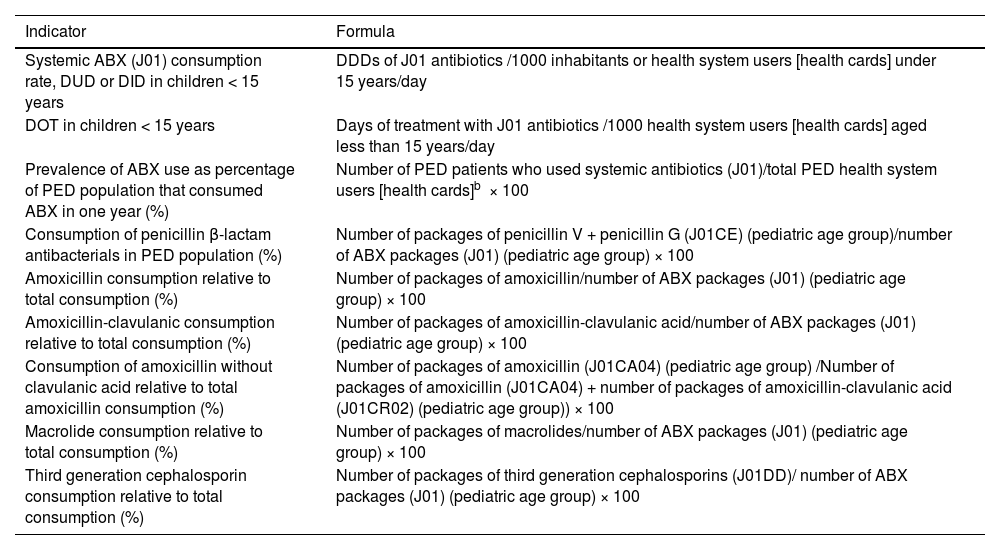

To study longitudinal trends in antibiotic prescribing, we used for reference the indicators recommended for PC pediatrics in the PRAN.22,23 We compared antibiotic prescription data, measured in terms of the PRAN indicators, in three periods: pre-pandemic (2014-2019), COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021) and (2022-2023), stratifying the data by age group (0-4, 5-9 and 10-14 years) as proposed in the PRAN.22 Other analyzed variables were age, year of prescription, basic health zone where the prescription was made and prescribed antibiotic (ATC classification). When it came to the specific metrics used in the analysis, we adhered to the recommendations of the PRAN for pediatric care, choosing the following indicators: systemic antibiotic (J01) prescribing rate in terms of the DUD (defined daily doses [DDDs] per 1000 health system users [holders of public health care system cards] per day in children aged less than 15 years); prevalence of antibiotic consumption in the pediatric population (proportion of the catchment pediatric population that consumed antibiotics in a year); consumption of penicillin β-lactam antibacterials relative to total systemic antibiotics (%); consumption of amoxicillin relative to total systemic antibiotics; consumption of macrolides relative to total systemic antibiotics; consumption of third-generation cephalosporins relative to total systemic antibiotics and consumption of amoxicillin without clavulanic acid relative to total amoxicillin consumption. Table 1 presents the definitions of the indicators used to measure antibiotic consumption and the formulas used for their calculation. We also calculated the days of therapy (DOT) indicator (number of treatment days/1000 IHCA cards), following the recommendation of other guidelines and documents focused on pediatric care, although, in our study, we only had information regarding the prescribed duration of treatment, as opposed to the number of days patients actually consumed the antibiotics.22–24 To facilitate the comparison of our findings to those of other studies conducted in Spain and abroad, we will refer to the DUD unit defined in the PRAN (DDDs per 1000 health system users per day) as DID. The DID unit corresponds to the DDDs per 1000 inhabitants per day, where one DDD is the assumed daily maintenance dose for the active ingredient.25

Indicators of antibiotic consumption in the pediatric age group in primary care.

| Indicator | Formula |

|---|---|

| Systemic ABX (J01) consumption rate, DUD or DID in children < 15 years | DDDs of J01 antibiotics /1000 inhabitants or health system users [health cards] under 15 years/day |

| DOT in children < 15 years | Days of treatment with J01 antibiotics /1000 health system users [health cards] aged less than 15 years/day |

| Prevalence of ABX use as percentage of PED population that consumed ABX in one year (%) | Number of PED patients who used systemic antibiotics (J01)/total PED health system users [health cards]b × 100 |

| Consumption of penicillin β-lactam antibacterials in PED population (%) | Number of packages of penicillin V + penicillin G (J01CE) (pediatric age group)/number of ABX packages (J01) (pediatric age group) × 100 |

| Amoxicillin consumption relative to total consumption (%) | Number of packages of amoxicillin/number of ABX packages (J01) (pediatric age group) × 100 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic consumption relative to total consumption (%) | Number of packages of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid/number of ABX packages (J01) (pediatric age group) × 100 |

| Consumption of amoxicillin without clavulanic acid relative to total amoxicillin consumption (%) | Number of packages of amoxicillin (J01CA04) (pediatric age group) /Number of packages of amoxicillin (J01CA04) + number of packages of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (J01CR02) (pediatric age group)) × 100 |

| Macrolide consumption relative to total consumption (%) | Number of packages of macrolides/number of ABX packages (J01) (pediatric age group) × 100 |

| Third generation cephalosporin consumption relative to total consumption (%) | Number of packages of third generation cephalosporins (J01DD)/ number of ABX packages (J01) (pediatric age group) × 100 |

Abbreviations: ABX, antibiotic; DID, defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day; DUD, defined daily doses per 1000 health system users per day; DOT, days of therapy; PED, pediatric.

aSince conventional metrics (DDD, number of packages, etc) have limitations for the purpose of measuring prescription practices in the pediatric age group, we propose evaluating the validity of the DOT indicator (days of treatment/1000 health system users [cards] < 15 years/day) in the primary care system and, should it prove valid, adding it to the established set of indicators.

The study adhered to the standards of good clinical practice (article 34 of Royal Decree 223/2004; Directive 2001/20/EC) and legislation concerning the protection of personal data and confidentiality (General Data Protection Regulation of the EU and Organic Law 3/2018 on the Protection of Personal Data and the Guarantee of Digital Rights). It was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research involving Medicines of Albacete (code: 05-2018), including the waiver of informed consent.

As regards the statistical analysis, we performed a descriptive analysis of the variables including calculation of proportions, measures of central tendency and measures of dispersion as applicable based on the type of variable, estimating the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to determine whether data followed a normal distribution. To analyze the association between two categorical variables, we used the χ2 test. To compare the use of antibiotics during the pandemic, prepandemic and postpandemic periods, we used the t-test for independent samples. To compare mean values in more than two independent groups, we used analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. We also compared antibiotic prescription in the three periods (2014-2019, 2020-2021 and 2022-2023) by means of ANOVA. We set the level of significance at 5% for all tests. The data were analyzed with SPSS version 25.0 and Epidat version 3.1.

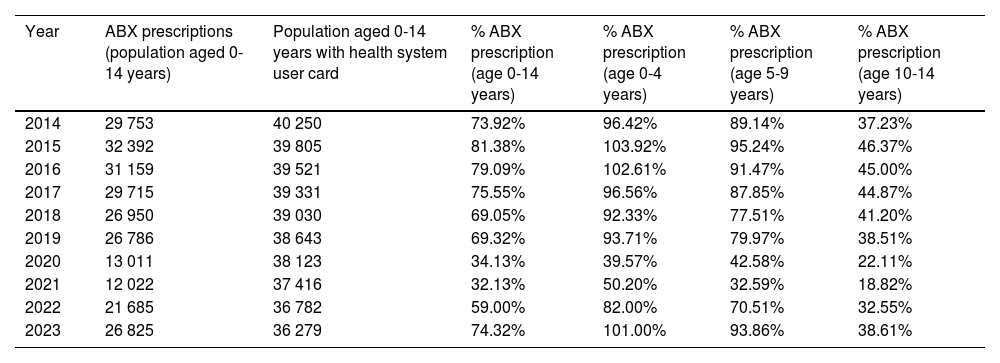

ResultsThe analysis included 250 498 antibiotic prescriptions made during the total study period. Overall, 65.0% (95% CI, 64.9%-65.2%) of the pediatric population served by the primary care centers of the IHCA of Albacete received some antibiotic drug at some point in the study period. Table 2 presents the frequency of antibiotic prescription, overall and stratified by age group, during the study period.

Frequency of systemic antibiotic (J01) prescription at the primary care level in the pediatric catchment population (≤14 years) of the Albacete health care system, overall and by age group (2014-2023).

| Year | ABX prescriptions (population aged 0-14 years) | Population aged 0-14 years with health system user card | % ABX prescription (age 0-14 years) | % ABX prescription (age 0-4 years) | % ABX prescription (age 5-9 years) | % ABX prescription (age 10-14 years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 29 753 | 40 250 | 73.92% | 96.42% | 89.14% | 37.23% |

| 2015 | 32 392 | 39 805 | 81.38% | 103.92% | 95.24% | 46.37% |

| 2016 | 31 159 | 39 521 | 79.09% | 102.61% | 91.47% | 45.00% |

| 2017 | 29 715 | 39 331 | 75.55% | 96.56% | 87.85% | 44.87% |

| 2018 | 26 950 | 39 030 | 69.05% | 92.33% | 77.51% | 41.20% |

| 2019 | 26 786 | 38 643 | 69.32% | 93.71% | 79.97% | 38.51% |

| 2020 | 13 011 | 38 123 | 34.13% | 39.57% | 42.58% | 22.11% |

| 2021 | 12 022 | 37 416 | 32.13% | 50.20% | 32.59% | 18.82% |

| 2022 | 21 685 | 36 782 | 59.00% | 82.00% | 70.51% | 32.55% |

| 2023 | 26 825 | 36 279 | 74.32% | 101.00% | 93.86% | 38.61% |

Abbreviation: ABX, antibiotic (group J01).

When we compared data on the prescription of group J01 drugs in the three age groups over the 10 year period, we found statistically significant differences between them (P < .01). The mean prevalence in the 0-4 years and 5-9 years age groups were significantly greater compared to the 10-14 years group (P < .01), without significant differences in the mean prevalence between the 0-4 years and 5-9 years groups.

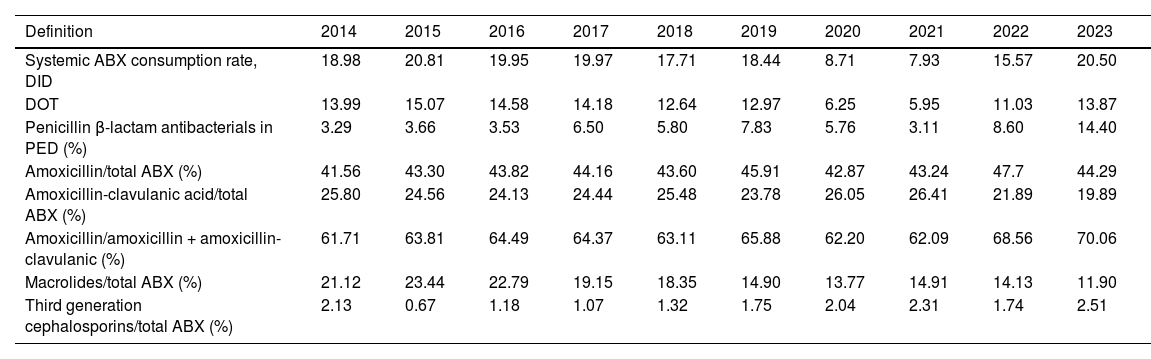

When it came to the rate of prescription of systemic antibiotics (J01), the mean in the period ranging from 2014 to 2023 was of 16.9 DID (SD, 4.76). Table 3 presents the changes in antibiotic use based on the consumption indicators in the pediatric age group recommended in the PRAN for PC. The largest difference in antibiotic prescription was of 12.9 DID (maximum of 20.8 in 2015 and minimum of 7.9 in 2021).

Changes in antibiotic consumption indicators in the population aged less than 15 years in the Albacete public health system (2014-2023).

| Definition | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic ABX consumption rate, DID | 18.98 | 20.81 | 19.95 | 19.97 | 17.71 | 18.44 | 8.71 | 7.93 | 15.57 | 20.50 |

| DOT | 13.99 | 15.07 | 14.58 | 14.18 | 12.64 | 12.97 | 6.25 | 5.95 | 11.03 | 13.87 |

| Penicillin β-lactam antibacterials in PED (%) | 3.29 | 3.66 | 3.53 | 6.50 | 5.80 | 7.83 | 5.76 | 3.11 | 8.60 | 14.40 |

| Amoxicillin/total ABX (%) | 41.56 | 43.30 | 43.82 | 44.16 | 43.60 | 45.91 | 42.87 | 43.24 | 47.7 | 44.29 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid/total ABX (%) | 25.80 | 24.56 | 24.13 | 24.44 | 25.48 | 23.78 | 26.05 | 26.41 | 21.89 | 19.89 |

| Amoxicillin/amoxicillin + amoxicillin-clavulanic (%) | 61.71 | 63.81 | 64.49 | 64.37 | 63.11 | 65.88 | 62.20 | 62.09 | 68.56 | 70.06 |

| Macrolides/total ABX (%) | 21.12 | 23.44 | 22.79 | 19.15 | 18.35 | 14.90 | 13.77 | 14.91 | 14.13 | 11.90 |

| Third generation cephalosporins/total ABX (%) | 2.13 | 0.67 | 1.18 | 1.07 | 1.32 | 1.75 | 2.04 | 2.31 | 1.74 | 2.51 |

Abbreviations: ABX, antibiotic; DID, defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day; PED, pediatric age group.

We found lesser variation in the DOT indicator compared to the DID in the prepandemic period (2014-2019), with a difference of less than 3 points between the years with the highest and lowest prescription figures. The mean DOT for systemic antibiotics between 2014 and 2023 was 12.1 (SD, 3.3).

When we compared prescribing expressed in terms of the DID and the DOT in the three age groups (0-4 years, 5-9 years and 10-14 years) for the entire study period, we found statistically significant differences (P < .01). Both metrics (DID and DOT) were significantly higher in children aged 0-4 years compared to children aged 10-14 years (P < .01) and in children aged 5-9 years compared to children aged 10-14 years (P < .01).

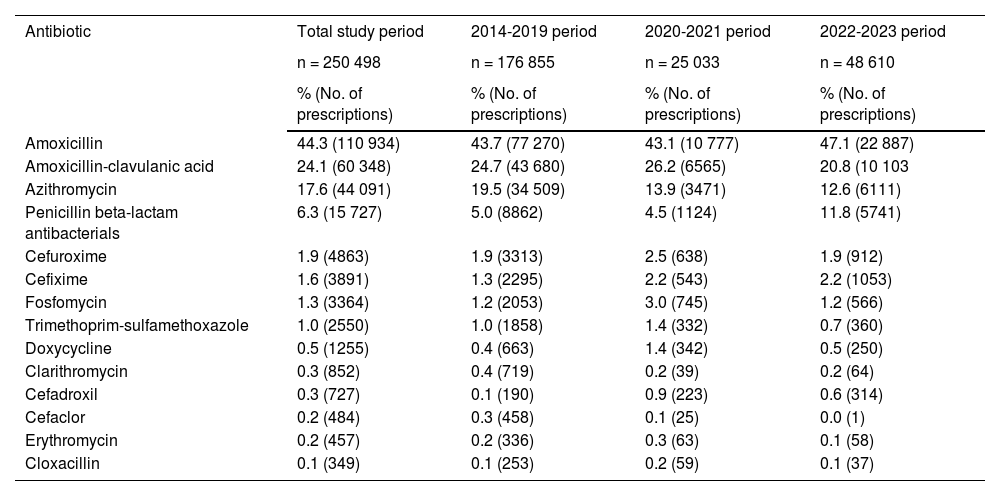

With regard to the distribution by antibiotic, amoxicillin was the most prescribed agent (44.3%; 95% CI, 44.1%-44.5% of total prescriptions during the entire study period), followed by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (24.1%; 95% CI, 23.9%-24.3%), macrolides, mainly azithromycin (18.2%; 95% CI, 18.0%-18.3%), and penicillin β-lactam antibacterials (6.3%; 95% CI, 5.9%-6.3%).

On the other hand, prescriptions of amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and azithromycin cumulatively amounted to 86% of the total prescriptions. Table 4 presents the distribution of prescribed antibiotics in each of the three periods under study, revealing an infrequent use of erythromycin, clarithromycin and cloxacillin.

Distribution of antibiotics prescribed to pediatric patients at the primary care level in the Albacete public health system by time period: pandemic (2021-2022), prepandemic (2014-2019) and postpandemic (2022-2023).

| Antibiotic | Total study period | 2014-2019 period | 2020-2021 period | 2022-2023 period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 250 498 | n = 176 855 | n = 25 033 | n = 48 610 | |

| % (No. of prescriptions) | % (No. of prescriptions) | % (No. of prescriptions) | % (No. of prescriptions) | |

| Amoxicillin | 44.3 (110 934) | 43.7 (77 270) | 43.1 (10 777) | 47.1 (22 887) |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 24.1 (60 348) | 24.7 (43 680) | 26.2 (6565) | 20.8 (10 103 |

| Azithromycin | 17.6 (44 091) | 19.5 (34 509) | 13.9 (3471) | 12.6 (6111) |

| Penicillin beta-lactam antibacterials | 6.3 (15 727) | 5.0 (8862) | 4.5 (1124) | 11.8 (5741) |

| Cefuroxime | 1.9 (4863) | 1.9 (3313) | 2.5 (638) | 1.9 (912) |

| Cefixime | 1.6 (3891) | 1.3 (2295) | 2.2 (543) | 2.2 (1053) |

| Fosfomycin | 1.3 (3364) | 1.2 (2053) | 3.0 (745) | 1.2 (566) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 1.0 (2550) | 1.0 (1858) | 1.4 (332) | 0.7 (360) |

| Doxycycline | 0.5 (1255) | 0.4 (663) | 1.4 (342) | 0.5 (250) |

| Clarithromycin | 0.3 (852) | 0.4 (719) | 0.2 (39) | 0.2 (64) |

| Cefadroxil | 0.3 (727) | 0.1 (190) | 0.9 (223) | 0.6 (314) |

| Cefaclor | 0.2 (484) | 0.3 (458) | 0.1 (25) | 0.0 (1) |

| Erythromycin | 0.2 (457) | 0.2 (336) | 0.3 (63) | 0.1 (58) |

| Cloxacillin | 0.1 (349) | 0.1 (253) | 0.2 (59) | 0.1 (37) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

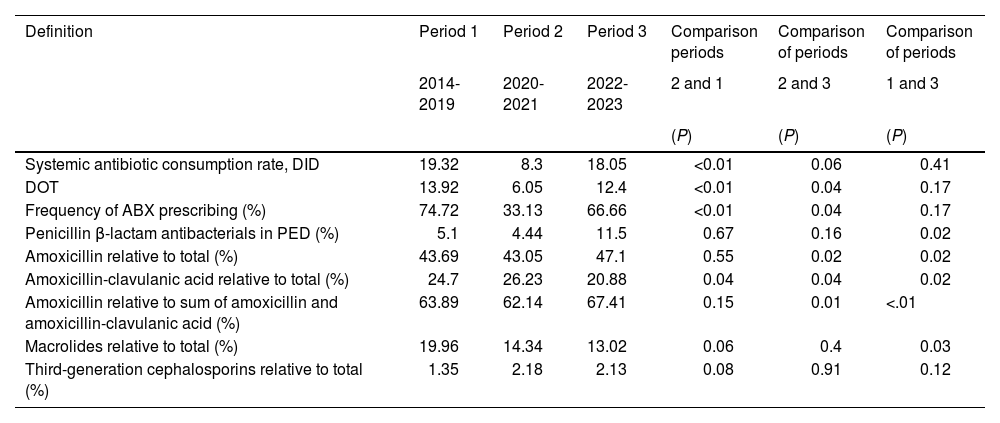

Table 5 compares antibiotic prescribing indicators in the three periods under study (2014-2019, 2020-2021 and 2022-2023), evincing differences between the periods in prescribing rates and DOT and in the frequency of antibiotic prescribing (P < .01). When we compared prescribing in the pandemic period (2020-2021) versus the prepandemic period, we found a reduction during the pandemic in terms of the DOT, DID and antibiotic prescribing frequency indicators (P < .01). The table also shows that the usage indicators for each antibiotic differed significantly between the three periods (P < .01) except in the case of third-generation cephalosporins.

Comparison of antibiotic consumption indicators in the population aged less than 15 years served by the public health system of Albacete between the pandemic (2021-2022), prepandemic (2014-2019) and postpandemic (2022-2023) periods.

| Definition | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Comparison periods | Comparison of periods | Comparison of periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014-2019 | 2020-2021 | 2022-2023 | 2 and 1 | 2 and 3 | 1 and 3 | |

| (P) | (P) | (P) | ||||

| Systemic antibiotic consumption rate, DID | 19.32 | 8.3 | 18.05 | <0.01 | 0.06 | 0.41 |

| DOT | 13.92 | 6.05 | 12.4 | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Frequency of ABX prescribing (%) | 74.72 | 33.13 | 66.66 | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Penicillin β-lactam antibacterials in PED (%) | 5.1 | 4.44 | 11.5 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| Amoxicillin relative to total (%) | 43.69 | 43.05 | 47.1 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid relative to total (%) | 24.7 | 26.23 | 20.88 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Amoxicillin relative to sum of amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (%) | 63.89 | 62.14 | 67.41 | 0.15 | 0.01 | <.01 |

| Macrolides relative to total (%) | 19.96 | 14.34 | 13.02 | 0.06 | 0.4 | 0.03 |

| Third-generation cephalosporins relative to total (%) | 1.35 | 2.18 | 2.13 | 0.08 | 0.91 | 0.12 |

Abbreviations: ABX, antibiotic; DID, daily defined doses per 1000 inhabitants per day; DOT, days of therapy; PED, pediatric age group.

The close association between antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial consumption demands continuous surveillance of the latter and, therefore, of antimicrobial prescribing.26 This requires the use of adequate indicators, such as the indicators recommended for the pediatric age group in the PRAN.22,23 Our findings show that during the study period, antibiotic prescribing in the pediatric population at the community level in the IHCA of Albacete was lower compared to prescribing in the general population both in Spain and in the European Union (EU), with a mean prescribing rate of 16.9 DID in the population under study compared to 23 DID in the general population in Spain and 17.7 DID in the EU.5,8

Annual trends in antibiotic prescribing in terms of the DID were also similar in the study sample and the general population in Spain and the EU, with a mild reduction in 2015 and 2019 followed by a sharp reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021) to then grow back to figures similar to those of the prepandemic period after the pandemic (2022-2023).5,8 The substantial reduction in antibiotic consumption during the pandemic was apparent in all European countries.5 The DOT indicator exhibited the same trend in our sample, although with lesser variation compared to the DID.

The analysis of antibiotic prescribing during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021) compared to the prepandemic period (2014-2019) and postpandemic period (2022-2023) revealed statistically significant differences, with a reduction in antibiotic use during the pandemic compared to the other two periods (P < .01). There may be limitations to the comparison of our results with those of previous studies on account of methodological differences and the lack of previous analyses comparing similar time periods. However, we were able to corroborate that our findings were consistent with those of studies conducted in Spain, which showed a clear reduction in the use of antibiotics in the pediatric population between the years preceding the pandemic and years 2020 and 2021.27 Other studies conducted in countries outside our area showed the same decreasing trend in antibiotic consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic.28

Antibiotic prescribing figures in the pediatric population of the IHCA of Albacete did not differ significantly from those described in other population-based studies in Spain. The mean frequency of prescription in our study was slightly lower compared to studies conducted in Aragón and Castilla y León10,13 and higher compared to a study carried out in Asturias between years 2005 and 2018.4

When we compared the prevalence of antibiotic use in our study stratified by age group, as recommended in the PRAN, we found that prescribing was significantly greater in children aged 0-4 years compared to the other two groups, probably because the incidence of most infections in children, including otitis and other respiratory tract infections, peaks between age 6 months and 2 years and tends to be lower from age 4 years.29,30 In addition, the prevalence found in children aged 0-4 years in our study was greater compared to studies conducted in other autonomous communities in Spain, although it must be taken into account that while they were conducted in similar time periods, the year intervals did not coincide exactly.12,13 The greater frequency of prescription in this age group compared to the other two (5-9 years and 10-14 years) is consistent with data published by the Ministry of Health.2 Although we do not know the specific reasons, the differences we found in comparison to previous studies11–13 may be attributable to the particular characteristics of the population or health care services in the area under study, as the frequency of some infections in children varies by age and geographical area.31

With respect to the most frequently prescribed antibiotics, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and azithromycin accounted for more than three fourths of total prescriptions. These results were consistent with those of previous studies on antibiotic prescribing at the primary care level in Spain.4,12 Also in agreement with our findings, studies conducted in other autonomous communities have evinced the frequent use of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid prescription.10,12,13 This is a puzzling phenomenon considering the low proportion of infections in children that are caused by β-lactamase-producing bacteria.32–34 Potential concerns regarding amoxicillin resistance may explain the more frequent prescription of other antibiotics, such as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, despite the fact that greater use of the latter is precisely more likely to promote the development of antimicrobial resistance mechanisms and cause more adverse effects.35 We also found, as described in previous studies,10,12,13 a high frequency of macrolide prescription that seems unwarranted considering that macrolides are not the first-line treatment for any of the most prevalent diseases and that, when it comes to the diseases for which antibiotics are most commonly prescribed, such as otitis or pharyngitis, they are only indicated in patients with immediate hypersensitivity reactions to β-lactam antibiotics, who are estimated to amount to only 1.7% to 5.2% of the pediatric population.32–34,36,37

On the other hand, our findings show an increase in the prescription of penicillin β-lactam antibacterials and amoxicillin in the postpandemic period compared to previous periods, as well as an increase in the use of amoxicillin without clavulanic acid relative the overall use of amoxicillin (amoxicillin + amoxicillin-clavulanic acid), with a reduction in the use of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and macrolides. Therefore, based on the improvement criteria defined in the PRAN,23 we found improvement in the use of antibiotics during the study period, as prescriptions showed an improvement in antibiotic selection. Third-generation cephalosporins were the drugs for which we did not find such an improvement, as the proportion of prescriptions containing it containing them increased in the second and third periods compared to the first. This increase in the use of cephalosporins may be due to the recommendation made in 2020 by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to avoid the use of oral fosfomycin in children aged less than 12 years, which resulted in an increase in the use of second- and third-generation cephalosporins for treatment of urinary tract infections.38 Another possible reason could be the shortages experienced in the last few years under study, resulting in a shift in prescribing toward antibiotics that were available, even if they were not the first-line treatment, and in additional prescriptions issued if the antibiotic that had been prescribed originally was not available in pharmacies. The shortage was particularly concerning in the case of penicillin β-lactam antibacterials and pediatric formulations of amoxicillin, prompting the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS) to take measures such as authorizing pharmacists to dispense amoxicillin in powder or tablet form instead of amoxicillin pediatric suspension. The shortage in pediatric amoxicillin formulations in every country in Europe led to shortages in other formulations of amoxicillin, alone or combined with clavulanic acid (tablets, capsules or sachets) and pediatric formulations of other active ingredients, such as azithromycin, penicillin or cefuroxime.39,40

The development of the PRAN and the establishment of ASPs probably played a role in the improving trends in antibiotic prescribing observed in our health care area, in line with the findings of previous studies.41,42 Furthermore, when we compared the three periods under study, we found a decrease in overall antibiotic consumption during the pandemic compared to the periods before and after it, and decreased consumption in the postpandemic period compared to the prepandemic period, although the latter difference was not statistically significant. These differences are probably due to a reduction in the volume of infectious diseases managed in the health care system during the pandemic than to increased awareness in the population and prescribing physicians.17–20 Future studies may confirm these improving trends in antibiotic prescribing, although the comparative analysis of indicators in the postpandemic and prepandemic periods did not identify statistically significant differences.

One of the main limitations of our study is the type of data used in the analysis. Thus, we did not have data regarding the clinical characteristics, course or management of the patients, which may have affected prescribing. However, this would apply to every year under study, minimizing the potential bias resulting from the impact of these aspects on the observed differences between periods. In addition, we only had access to prescription data, and not to dispensation or consumption data, so the analysis may have overestimated antibiotic consumption. Another limitation to consider is the modifications made by the World Health Organization to the DDDs of certain antibiotics used at the community level, which affected the calculation of antibiotic consumption rates in the European Union and the ranking of European countries by antibiotic consumption levels. The modifications had a particular impact in Spain, resulting in an overall reduction in the overall antibiotic consumption rate, as they involved, among others, the two most widely used antibiotics at the outpatient level, amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, with the DDD changing from 1 to 1.5 g in both cases. Lastly, we ought to highlight the challenges in comparing our findings with those of other population-based studies, as there are few of them and the study periods do not match exactly.

In conclusion, we found an overall reduction in antibiotic prescribing at the community level based on the indicators recommended in the PRAN for PC pediatrics as well as an improvement in antibiotic use trends over time. Notwithstanding, the use of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and macrolides continues to be high, so it is important that clinical practice guidelines are not only disseminated but also implemented.

We also found differences in prescribing in relation to age, with a greater frequency in children aged 0 to 4 years, so strategies and programs that target this specific group need to be implemented, although it is important not to neglect other age groups.

Last of all, as the PRAN and other studies indicate, we ought to highlight the value of the DOT indicator for measurement of antibiotic consumption in the pediatric age group, although further studies and registries that use this indicator are required to allow comparison of results.