Due to the complexity and characteristics of their patients, neonatal units are risk areas for the development of adverse events (AE). For this reason, there is a need to introduce and implement some tools and strategies that will help to improve the safety of the neonatal patient. Safety check-lists have shown to be a useful tool in other health areas but they are not sufficiently developed in Neonatal Units.

Material and methodsA quasi-experimental prospective study was conducted on the design and implementation of the use of a checklist and evaluation of its usefulness for detecting incidents. The satisfaction of the health professionals on using the checklist tool was also assessed.

ResultsThe compliance rate in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) was 56.5%, with 4.03 incidents per patient being detected. One incident was detected for every 5.3 checklists used. The most frequent detected incidents were those related to medication, followed by inadequate alarm thresholds, adjustments of the monitors, and medication pumps.

The large majority (75%) of the NICU health professionals considered the checklist useful or very useful, and 68.75% considered that its use had managed to avoid an AE. The overall satisfaction was 83.33% for the professionals with less than 5 years working experience, and 44.4% of the professionals with more than 5 years of experience were pleased or very pleased.

ConclusionThe checklists have shown to be a useful tool for the detection of incidents, especially in NICU, with a positive assessment from the health professionals of the unit.

Las unidades neonatales, por su complejidad y las características de los pacientes, son áreas de riesgo para el desarrollo de eventos adversos (EA); de ahí surge la necesidad de implantar e implementar herramientas y estrategias que permitan mejorar la seguridad del paciente neonatal. Las listas de verificación de seguridad (LVS) han demostrado ser una herramienta útil en otras áreas sanitarias, pero están poco estudiadas en neonatología.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo cuasiexperimental. Diseño e implantación del uso de LVS y valoración de su utilidad para la detección de incidentes, así como valoración de la satisfacción con el uso de esta herramienta por parte del personal sanitario.

ResultadosEn la unidad de cuidados intensivos neonatales (UCIN) el cumplimiento fue del 56,5%. Se detectaron 4,03 incidentes por cada paciente ingresado. Para detectar un incidente fue necesario realizar 5,3 LVS. Los incidentes más frecuentes fueron los relacionados con medicación, seguidos por los ajustes inadecuados de las alarmas de monitores y bombas de infusión.

El 75% del personal consideró la LVS útil o muy útil y el 68,75%, que la LVS había conseguido evitar algún EA. En cuanto al grado de satisfacción global, se sentían satisfechos o muy satisfechos con la LVS el 83,33% de las personas con menos de 5 años de experiencia frente al 44,4% del personal con más de 5 años de experiencia.

ConclusionesLas LVS han demostrado ser una herramienta útil para la detección de incidentes, especialmente en la UCIN, con una valoración positiva por parte del personal de la unidad.

In the past 25 years, following the publication of the study To err is human: Building a safer health system,1 national and international health authorities have made considerable efforts to improve patient safety.

There have been advances in safety in the field of paediatrics, too,2–4 but the safety of neonatal patients has not been adequately studied, despite the high incidence of adverse events (AEs) in this group.5,6 Neonatal units, and especially those devoted to intensive care, are risk areas for the development of AEs on account of their complexity and the characteristics of their patients.5–8 Thus, it is necessary to introduce and implement tools and strategies that allow the detection of incidents and that protect against and help reduce AEs. Voluntary AE reporting systems underestimate the prevalence of these incidents, so the use of other tools for the active search of AEs, such as safety checklists (SCLs) can complement reporting and improve detection, which allows us to learn more from our mistakes. The WHO has promoted the use of SCLs both in surgery9 and childbirth.10 Within the framework of a plan for improving patient safety in the department of neonatology of our hospital, we decided to assess the potential usefulness of SCLs for the detection and correction of incidents and the prevention of AEs.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a prospective, quasiexperimental study in the Department of Neonatology of the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón between March and September of 2015. The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the hospital, and received no funding.

The neonatal department offers care at the IIIC level and serves patients with any type of neonatal disease. It has two separate inpatient areas—an intermediate care unit with 34 beds, and a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) with 16 beds—and a staff comprising 91 nurses, 55 nursing assistants, 19 physicians and a department chief, in addition to staff in training. The department has electronic health records and prescription systems, although physicians occasionally make adjustments to treatments by means of hand-written prescriptions.

Two SCLs were created, one for each unit (Appendices A and B). They were developed by a working group consisting of neonatologists and preventive medicine physicians based on the AEs and incidents described in the literature and the voluntary reports submitted the previous year, in addition to their own personal experience.

We collected data for variables pertaining to:

- -

Patient identification: due to the serious consequences that errors in identification may have. We considered that a patient was identified correctly if the patient was wearing an identification band whose information was the same as the information in the crib, the treatment sheet and the nursing chart.

- -

Medication: because medication errors are among the most frequent errors described in the literature. Checking the medication prescription sheet (drug, dose, route of administration, interval between doses, formulation) and the correct transcription to the nursing chart.

- -

Respiratory support: due to the significant consequences that errors in this area may have. Type of support, checking of respiratory parameters, humidifier, temperature, secure attachment of endotracheal tube, and integrity of nasal mucosa and skin.

- -

Checking that the settings for the alarms in monitoring devices and other equipment are correct: each patient has a different problem and requires personalised care, and therefore the thresholds for alarms, both in vital signs monitoring and other devices, must be set individually. For instance, it is essential to monitor oxygen saturation in preterm newborns, in whom hyperoxygenation must be prevented, or to monitor cardiac patients for the presence of pulmonary hypertension or low cardiac output. Similarly, adequate settings in drug infusion pumps can help detect dosing errors early on, and adequate pressure threshold presets in pumps allow the detection of problems such as thrombosis or extravasation.

- -

Nutrition: due to the severe consequences that errors in nutrition may have on occasion. Type of nutrition, amount and rate of infusion, route of administration, verification of correct functioning and adequate placement and secure attachment of feeding tube.

- -

Vascular access lines: with the purpose of reducing the risk of nosocomial infection and catheter-related complications. Verification of correct identification (following the protocol of our hospital), of continued need for access line, integrity of the skin at the site of insertion and along the catheter trajectory, catheter functioning and tissue perfusion. Infusion of medication using the line specified in the prescription.

- -

Urinary catheter: with the purpose of reducing the incidence of urinary tract infections. Indication of sustained catheter use, verification of closed system.

- -

Watching for ulcer development.

The entire staff participated in information sessions in the month prior to the introduction of the SCLs.

The SCLs were filled out in cooperation by the medical and nursing staff in charge of the patient. In the NICU, SCLs were completed 3 times a day (once per shift), as there are frequent changes in treatment and supportive care in its patients. In the intermediate care unit, it was completed once a day during the morning shift, as changes are less frequent throughout the day compared to the NICU.

Data analysis and descriptionWe have expressed categorical data as percentages and quantitative data as means with standard deviations (SDs) or medians with their interquartile range (IQR) based on whether their distribution was or was not normal. We compared categorical variables by means of the chi square test or Fisher's exact test (when the observed frequencies were less than 5). We analysed the differences between diagnostic groups by the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test.

To assess the adherence to the performance of SCLs, we calculated the adherence rate, defined as the number of SCLs performed divided by the number of expected SCLs (that is, the total that should have been performed in the total of patients admitted during the study period) and multiplied by 100.

For the intermediate care unit, we estimated patient days and the SCLs that should have been performed (1 SCL/day) based on the mean length of stay in the unit (in days) multiplied by the number of patients admitted during the study period.

For the NICU, we calculated the expected frequency of SCLs by multiplying the total number of patient days by 3 (1 SCL/shift, with 3 shifts per day).

We assessed the yield of SCLs based on the number of SCLs required to detect an incident, the type and the severity of incidents detected. The severity of incidents was rated on the following scale: (1) potential harm that did not occur; (2) temporary or minor harm (requires observation or treatment); (3) moderate harm (requires or prolongs hospitalisation); (4) serious harm (permanent or requiring intervention); (5) contributing to or resulting in the patient's death.11

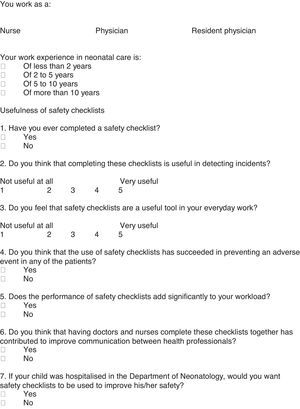

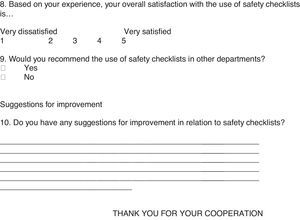

At the end of the study period, we conducted a survey of the NICU personnel, excluding staff in training. The survey was designed by the team that had developed the SCLs to assess the perceptions of health care staff regarding the usefulness of the SCL (Appendix C).

ResultsIntermediate care unitWe performed an analysis 4 months after initiating the study. A total of 267 newborns were hospitalised in the unit during this period. The mean length of stay in 2015 was 13.31 days/patient.

The adherence rate was 23.1% (821/3553.77). At least 1 SCL was performed in 66.66% of the admitted patients.

A total of 821 SCLs were completed, and 29 incidents detected. The detection of 1 incident required completion of 28.31 SCLs, and 1 incident was detected per 9.2 admitted patients.

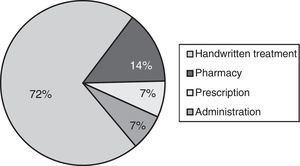

Table 1 presents the types of incidents that were detected. The most frequent incidents involved medication, and among them, the most common were prescription errors, followed by dispensation and administration errors (Fig. 1). The severity of 100% of detected incidents was of type 1, that is, potential harm that did not ultimately take place.

During the period under study, 174 patients were admitted to the NICU and stayed for a total of 2207 patient days.

The staff completed 3727 SCLs. At least 1 SCL was completed for 140 patients (80.5%).

The SCL adherence rate was 56.5%.

Performance of SCLs resulted in the detection of 702 incidents. It took 5.3 SCLs to detect 1 incident, and 4.03 incidents were detected per patient.

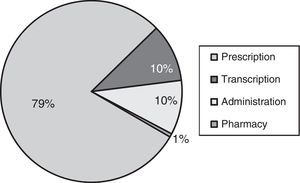

When it came to the type of incidents, the most frequent ones involved medication, followed by inadequate alarm settings in monitoring devices and infusion pumps (Table 2). Most medication incidents corresponded to prescription errors, followed by errors in administration and transcription (Fig. 2).

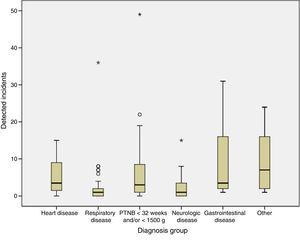

Types of incidents detected in the intensive care unit.

| Type of incident | n/N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Medication | 320/702 | (44) |

| Alarms | 144/702 | (20) |

| Peripheral access | 48/702 | (7) |

| Humidifier/gas heater | 28/702 | (4) |

| Central line | 26/702 | (4) |

| Ulcers (except nasal ones) | 26/702 | (4) |

| Associated with enteral nutrition | 23/702 | (3) |

| Associated with endotracheal tube | 20/702 | (3) |

| Associated with patient identification | 18/702 | (3) |

| Associated with noninvasive ventilation | 10/702 | (1) |

| Nasal ulcers | 9/702 | (1) |

| Associated with the ventilator | 7/702 | (1) |

| Other | 23/702 | (3) |

The consequences of the detected incidents were potential harm that did not occur in 73.9% of cases and temporary or minor harm in 26.1%.

Fig. 3 represents the distribution of incidents by the pathology of the patient. The differences between groups were statistically significant (Kruskal–Wallis H, P=.01).

The survey on staff satisfaction in relation to the use of SCLs was completed by 48 employees (54% of the staff), 10 doctors and 38 nurses, a difference that was not statistically significant (P=.501). When it came to the usefulness of SCLs, 75% (36/48) considered that SCLs were useful or very useful, 14.58% (7/48) felt indifferent, and 10.42% (5/48) considered them of little use or useless. Of all respondents, 68.75% (33/48) believed that SCLs had succeeded in preventing some AEs. In addition, 87.5% (42/48) of respondents did not feel that SCLs added significantly to their work burden. As for the level of overall satisfaction with SCLs, 54.16% (26/48) reported feeling satisfied or very satisfied, 31.25% (15/48) indifferent and 14.58% (7/48) dissatisfied. One hundred percent of respondents replied Yes to the question “if your child was hospitalised in the neonatology department, would you like safety checklists to be implemented to improve their safety?”.

The percentage of respondents that considered SCLs useful or very useful was 75% (36/48), with no differences between the subset of the staff that had less than 5 years’ work experience (9/12) and the subset of more experienced staff (27/36) (P=.64). As for the level of overall satisfaction, 83.33% (10/12) of the staff with fewer than 5 years’ experience were satisfied or very satisfied with SCLs, compared to 44.4% (16/36) of the staff with more than 5 years’ experience, a difference that was statistically significant (P=.023).

When it came to professional category, we found statistically significant differences in the perception of the usefulness of SCLs: 100% (10/10) of doctors found them very useful, compared to 68.4% (23/38) of nurses (P=.048). There was also a significant difference in the level of satisfaction associated with the use of SCLs, with 90% (9/10) of doctors reporting being satisfied, compared to 50% (19/38) of nurses (P=.031).

DiscussionThe use of SCLs is widespread in several health care fields, such as surgery, in which the WHO has promoted the use of SCLs in the operating theatre as part of the Safe Surgery Saves Lives initiative,9 which has been associated with a reduction in surgery-related mortality and complications.12 Furthermore, the WHO has developed a safe childbirth checklist, conceived as a tool to improve maternal care during birth.10

However, SCLs are a poorly studied tool in the field of neonatology. It is estimated that there are between 30 and 74 adverse events per 100 patients hospitalised in neonatal units.13,14 It is of vital importance that we investigate tools that allow us to detect these incidents more thoroughly in order to improve the safety of neonatal patients.

To our knowledge, this is the first published study on the usefulness of SCLs for the detection and prevention of incidents that may impact patient safety in a neonatology setting.

According to our results, SCLs were particularly useful in the NICU, where its use allowed the detection of 1 incident per 5.3 completed SCLs, compared to the intermediate care unit, where detecting a single incident required performance of 29.3 SCLs.

In the intermediate care unit, during the 4 months when the SCL was being used, adherence was low and the interim analysis at 4 months demonstrated that only 28 incidents had been detected, and none of them were serious. The incidents detected most frequently involved medication, which is consistent with the literature published to date.6,7,15,16

In the NICU, however, there was a higher degree of adherence to SCLs (56.5%). Once again, the incidents detected most frequently were those associated with medication (44%). Within this type, the most frequent incidents were prescription errors, which amounted to 79%. This finding is particularly relevant, as it demonstrates that despite all the measures implemented in our hospital to reduce these errors (electronic prescription, protocols, automated infusion pumps), this continues to be a problem deserving further investigation and the implementation of new preventive tools and strategies. In a recent study conducted in Spain,7 prescription errors amounted to 39.5% of all detected medication errors, and administration errors were the most frequent type of medication error (68.1%). There are barriers to comparing the findings of this study with our own, as voluntary incidence reports were the source of data in the former, while we used SCLs to obtain data for our study. Other published studies that used data from voluntary reporting have also found a greater proportion of administration errors.15,17

The detected incidents were analysed, and corrective measures were implemented to prevent or reduce the likelihood of their recurrence.

The higher yield of SCLs in the NICU compared to the intermediate care unit was reinforced by the consequences of the detected incidents. While in the intermediate care unit 100% of the consequences were rated as potential harm that did not ultimately occur, 26.1% of incidents in the NICU resulted in temporary or minor harm. Furthermore, only 0.1 incidents per admitted patient were detected in intermediate care, compared to 4.3 in the NICU. Given the low yield of the SCL in the intermediate care unit, its use was discontinued 4 months after its introduction. A new SCL is currently being developed to better fit the needs of this unit.

In our opinion, the greater usefulness and adherence to SCLs in the NICU may be due to several factors. On one hand, to the greater complexity and instability of NICU patients, who also require more complex treatments and techniques. On the other, these patients frequently require treatment changes. Furthermore, the higher nurse-to-patient and doctor-to-patient ratios increases the availability of staff for conducting SCLs. Establishing the causes of the differences between the units would require a more detailed analysis and a different approach to the one adopted in this study, and may be the subject of future studies.

Another of our objectives following the introduction of the SCLs was to make a survey of the attitudes of the NICU staff regarding their use. We ought to highlight that 68.75% of the staff that responded to the anonymous satisfaction survey considered that the use of SCLs had succeeded in preventing AEs, and 87.5% felt it did not add significantly to their workload. Although overall satisfaction was lower—as only 54.16% felt satisfied or very satisfied—100% responded that if a family member were to be admitted to the unit, they would want SCLs to be used.

One salient finding was the difference in the overall satisfaction reported based on the years of work experience, as the proportion of satisfied or very satisfied respondents was nearly double in the staff with fewer than 5 years’ experience compared to more experienced staff (83.3% vs. 44.4%). Less experienced staff perceived SCLs as more useful, which means that these lists can be a useful tool for improving patient safety in units with high staff turnover rates.

In our experience, SCLs have proven useful in the detection and prevention of incidents in the NICU setting. Furthermore, their use has generated a specific culture and systematic approach to everyday's work, establishing the habit of checking on every patient's treatment and monitoring. On the other hand, their use forces health care staff to regularly reassess the need to continue using peripheral or central access lines and urinary catheters, removing them once they become unnecessary, which may contribute to reducing the risk of nosocomial infection. Their use promotes a patient safety culture, which is particularly important for staff in training or newly hired.

We are aware of the limitations of our study, for while we demonstrated the usefulness of SCLs for the purpose of detecting incidents in our unit, it would be important to assess whether this had a direct impact on our patients, with a reduction in the incidence of health care-associated complications. This would be difficult to establish, as many factors influence the development of these complications, and variations in the latter could not be solely attributed to the use of SCLs. It is important that we continue refining this safety tool to achieve greater adherence and increase the satisfaction of the health care staff.

In conclusion, SCLs have proven to be a useful tool for the detection of incidents, especially in the NICU, that increases our knowledge on patient safety and is perceived positively by the staff of the unit.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

| Date | Hour | Date | Hour | Date | Hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient identification | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Check treatment sheet | |||||

| Check monitor and pump alarms | |||||

| Respiratory | |||||

| CPAP/nasal prongs | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Respiratory parameters check | |||||

| Nose sore check | |||||

| Humidifier/heater check | |||||

| Nutrition | |||||

| Enteral | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| OGT/NGT check | |||||

| PNT | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Infusion rate check | |||||

| Vascular access | |||||

| Silastic catheter | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Access necessary? | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Check for phlebitis signs | |||||

| Peripheral access | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Is catheter needed? | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Check correct functioning | |||||

| Check for phlebitis | |||||

| Urinary catheter | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Closed system | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Catheter needed? | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Ulcers | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Incident detected | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| Incident reported | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | ||

| N. detected incidents | |||||

| Nurse signature | |||||

| Physician signature | |||||

| Free text. Incident description | Free text. Incident description | Free text. Incident description | |||

CPAP, ventilation with continuous positive airway pressure; NGT, nasogastric tube; OGT, orogastric tube; PNT, parenteral nutrition.

| Date | Morning | Evening | Night | Date | Morning | Evening | Night |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hour | |||||||

| Patient identification | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Check treatment sheet | |||||||

| Check correct transcription | |||||||

| Respiratory | |||||||

| CPAP/SNIPPV/prongs | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| MV | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Check parameters | |||||||

| Check ETT placement/securement | |||||||

| Check humidifier/heater | |||||||

| Check for nasal ulcers | |||||||

| Check alarms in monitors and pumps | |||||||

| Nutrition | |||||||

| Enteral | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| OGT/NGT check | |||||||

| PNT | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Infusion rate check | |||||||

| Check prescribed intervals | |||||||

| Vascular access | |||||||

| Arterial | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Access identified | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Access necessary? | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Check insertion site | |||||||

| Check extremity perfusion | |||||||

| Central access | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Line identified | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Is access necessary? | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Verification of adequate perfusion | |||||||

| Check for signs of occlusion | |||||||

| Silastic catheter | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Catheter necessary? | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Check for signs of phlebitis | |||||||

| Peripheral access | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Is access necessary? | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Check correct functioning | |||||||

| Check for phlebitis | |||||||

| Urinary catheter | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Catheter needed? | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Ulcers | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Incident detected | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Incident reported | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | Yes No | |

| N. detected incidents | |||||||

| Nurse signature | |||||||

| Physician signature | |||||||

| Free text. Incident description | Free text. Incident description | ||||||

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; ETT, endotracheal tube; MV, invasive mechanical ventilation; NGT, nasogastric tube; OGT, orogastric tube; PNT, parenteral nutrition; SNIPPV, synchronized nasal intermittent positive-pressure ventilation.

We would like to ask you a series of questions regarding the use of safety checklists in the Department of Neonatology.

The information that we are requesting will be processed by means of software to perform statistical analyses in an ANONYMOUS manner, without recording any personal data and in compliance with Organic Law 15/1999 on the Protection of Personal Data.

Please cite this article as: Arriaga Redondo M, Sanz López E, Rodríguez Sánchez de la Blanca A, Marsinyach Ros I, Collados Gómez L, Díaz Redondo A, et al. Mejorando la seguridad del paciente: utilidad de las listas de verificación de seguridad en una unidad neonatal. An Pediatr (Barc). 2017;87:191–200.

Previous presentation: this study was presented in part at the 33rd Congress of the Sociedad Española de Calidad Asistencial (SECA); October 14–16, 2015; Gijón, Spain.