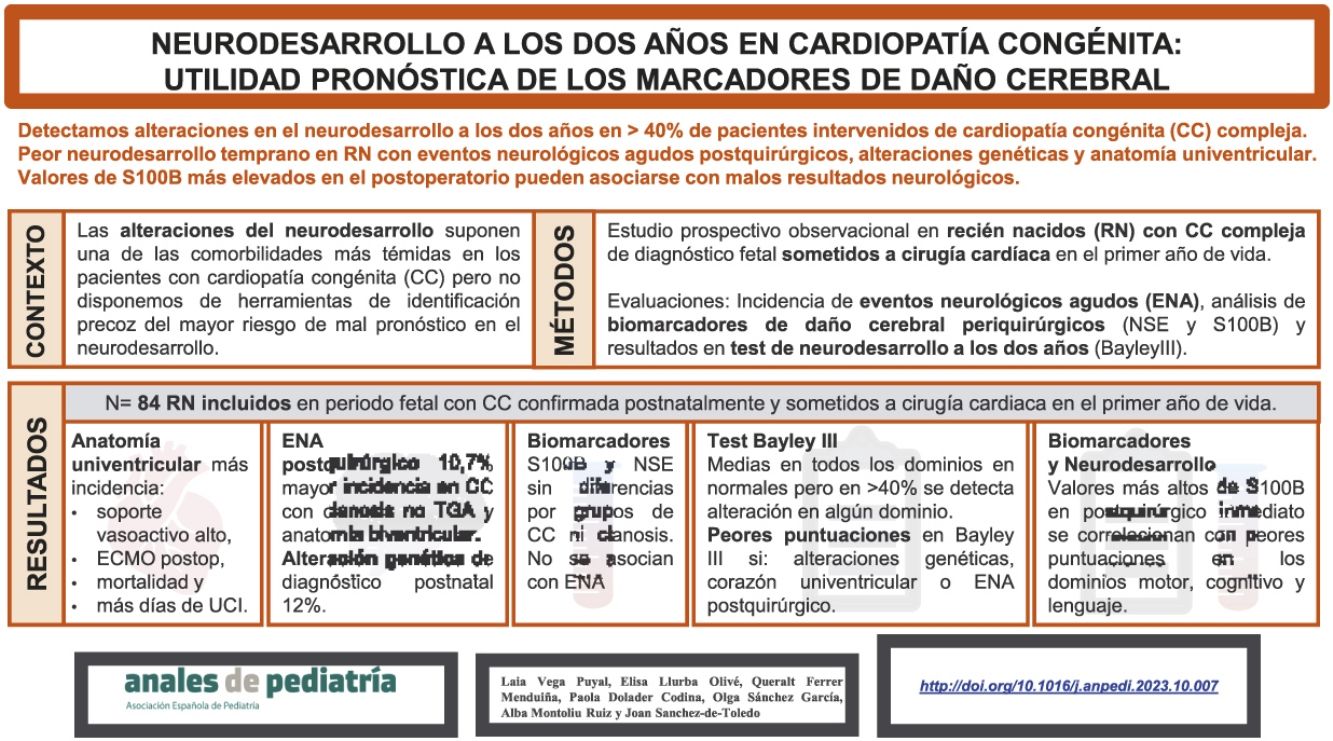

At present, neurodevelopmental abnormalities are the most frequent type of complication in school-aged children with congenital heart disease (CHD). We analysed the incidence of acute neurologic events (ANEs) in patients with operated CHD and the usefulness of neuromarkers for the prediction of neurodevelopment outcomes.

MethodsProspective observational study in infants with a prenatal diagnosis of CHD who underwent cardiac surgery in the first year of life. We assessed the following variables: (1) serum biomarkers of brain injury (S100B, neuron-specific enolase) in cord blood and preoperative blood samples; (2) clinical and laboratory data from the immediate postnatal and perioperative periods; (3) treatments and complications; (4) neurodevelopment (Bayley-III scale) at age 2 years.

Resultsthe study included 84 infants with a prenatal diagnosis of CHD who underwent cardiac surgery in the first year of life. Seventeen had univentricular heart, 20 left ventricular outflow obstruction and 10 genetic syndromes. The postoperative mortality was 5.9% (5/84) and 10.7% (9/84) patients experienced ANEs. The mean overall Bayley-III scores were within the normal range, but 31% of patients had abnormal scores in the cognitive, motor or language domains. Patients with genetic syndromes, ANEs and univentricular heart had poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes. Elevation of S100B in the immediate postoperative period was associated with poorer scores.

Conclusionschildren with a history of cardiac surgery for CHD in the first year of life are at risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Patients with genetic syndromes, ANEs or univentricular heart had poorer outcomes. Postoperative ANEs may contribute to poorer outcomes. Elevation of S100B levels in the postoperative period was associated with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years. Studies with larger samples and longer follow-ups are needed to define the role of these biomarkers of brain injury in the prediction of neurodevelopmental outcomes in patients who undergo surgery for management of CHD.

En la actualidad, las alteraciones del neurodesarrollo son la complicación más frecuente en pacientes con cardiopatía congénita (CC) en edad escolar. Analizamos la incidencia de eventos neurológicos agudos (ENA) en pacientes con CC sometidos a cirugía cardiaca y la utilidad de los neuromarcadores para predecir el neurodesarrollo.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo observacional en recién nacidos (RN) con CC diagnosticada prenatalmente sometidos a cirugía el primer año de vida. Se evaluaron: 1) biomarcadores sanguíneos de lesión cerebral (S100B, enolasa neuronal específica) en sangre de cordón y periquirúrgicos; 2) datos clínicos y analíticos perinatales y periquirúrgicos; 3) tratamientos y complicaciones; 4) neurodesarrollo (Escala Bayley III) a los dos años.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 84 RN con CC de diagnóstico fetal, confirmada postnatalmente, sometidos a cirugía cardiaca en el primer año de vida. 17 pacientes tenían corazón univentricular, 20 pacientes obstrucción izquierda y 10 síndromes genéticos. Fallecieron en el periodo postquirúrgico 5 pacientes (5,9%) y 9 pacientes presentaron ENA (10,7%). Las puntuaciones medias en el test de Bayley III fueron normales pero el 31% tuvieron alteración cognitiva, motora o en el lenguaje. Los pacientes con síndromes genéticos, ENA y CC univentriculares tuvieron peor neurodesarrollo. La elevación de S100B en el postoperatorio inmediato se correlacionó con peores puntuaciones.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con CC sometidos a cirugía tienen mayor riesgo de sufrir alteraciones del neurodesarrollo. Los pacientes con síndromes genéticos o corazones univentriculares presentan peores resultados. Presentar ENA postquirúrgico puede contribuir a peores resultados. Niveles de s100B elevados en el postoperatorio se correlacionan con peores resultados en los tests de neurodesarrollo a los dos años. Series con más pacientes y con seguimiento a largo plazo nos ayudarán a definir el papel de estos biomarcadores de lesión cerebral en la predicción del neurodesarrollo en pacientes sometidos a cirugía de CC.

The mortality associated with congenital heart disease (CHD) has decreased in the past few decades. More than 85% of affected patients survive to adulthood. This increase in survival has evinced the associated comorbidities that have a negative impact on quality of life.1 Neurodevelopmental abnormalities are currently the most frequent comorbidity found in school-aged children with CHD.2 Acute neurologic events (ANEs) or neurologic complications are among the most feared comorbidities in patients with CHD, but their role as predictors of long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes has not been clearly established.3

Neurodevelopmental disorders have a multifactorial aetiology, with prenatal, neonatal and perioperative factors contributing to long-term neurologic outcomes.4–6 In recent decades, the usefulness of various instruments and measures for the early prediction of poor neurologic outcomes has been investigated, including the association of biomarkers of brain injury with the development of neurologic events and abnormalities in the long term.7,8

We present the results of a study designed to identify risk factors for neurodevelopmental disorders in newborns with CHD treated with cardiac surgery. The objectives of the study were: (a) to determine the incidence of ANEs in patients with complex CHD treated with cardiac surgery, (b) to assess neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 2 years in a cohort of children with complex CHD treated with cardiac surgery and (c) to assess the usefulness of biomarkers of brain injury measured in the cardiac surgery perioperative period to predict the occurrence of ANEs in the postoperative period and poor neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Patients and methodsWe conducted a prospective observational study of newborns who received a prenatal diagnosis of CHD and treated with cardiac surgery within 1 year post birth at the Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebrón. The enrolment period lasted 4 years (2012–2016 for pregnant women and 2013–2017 for infants). We excluded cases of foetal death, antenatal detection of genetic disorders and of CHD associated with other major congenital anomalies.

The studied cohort is part of a multicentre study that recruited and assessed pregnant women with healthy foetuses and foetuses with CHD, the methodology of which has been described in a previous publication.9 We analysed demographic, clinical, laboratory and treatment-related variables, documented postoperative complications and measured serum markers of brain injury. The neurodevelopmental assessment was conducted at age 2 years by means of the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III).

Clinical and demographic variablesWe collected data on clinical and laboratory variables in the postnatal and perioperative period: sex, gestational age, preterm birth, anthropometric measurements, weight and height circumference percentiles and z scores, type of surgical repair, age at time of surgery, scores in surgical mortality risk scales, duration of extracorporeal circulation (ECC) and genetic disorders diagnosed after birth. Every newborn underwent a postnatal ultrasound examination to confirm the prenatal diagnosis. Infants were classified into 4 groups based on the cardiac anatomy and physiology (univentricular [UV] or biventricular [BV]) and whether there were lesions obstructing systemic blood (systemic obstruction: SO vs no SO). They were also classified in 3 groups based on the degree of cyanosis: (1) no cyanosis, (2) moderate neonatal cyanosis (cyanotic defect other than transposition of the great arteries [TGA]) and (3) cyanosis associated with TGA, as previously done by other authors.5,8,10

Treatments, complications and acute neurologic eventsWe collected variables pertaining to postoperative care, received treatment and postoperative complications including ANEs. We documented the mortality risk score at admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), the duration of mechanical ventilation, the use of vasoactive drugs, the length of stay in the ICU, the length of stay in hospital, the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) after surgery, complications in the postoperative period and postoperative mortality.

We defined ANE as intracranial bleeding, stroke, venous sinus thrombosis, seizures (clinical, electrographic or both) or brain death. The diagnosis of ANE was based on the findings of imaging tests ordered as the care team considered necessary. We did not include temporal changes in the definition of ANE. When available, diagnostic images were compared with previous imaging to verify the timing of development of the radiological features.

We documented suspected or confirmed postnatal diagnoses of genetic disorders and their association with neurodevelopmental outcomes, whether or not the association had been described in the previous literature.

Biomarkers of brain injuryWe analysed the levels of 2 biomarkers of brain injury: S100 calcium-binding protein B (S100B) and neuron-specific enolase (NSE). Blood samples were collected at 4 time points: (1) immediately after birth (cord blood), (2) immediately before surgery, (3) at admission to the ICU after surgery and (5) at 24 h from admission to the ICU after surgery. The samples were collected from central venous or arterial catheters already in place, extracting the minimum necessary volume (EDTA collection tube, 0.5 mL). Samples were processed by separating the plasma through centrifugation at 1400 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and frozen immediately after for storage at −80 °C until testing. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed in duplicate with commercial kits (BlueGene Biotech CO. Ltd, Shanghai, China). The minimum detection limits in the assays were 50 pg/mL for S100B and 0.5 ng/mL for NSE.

Follow-up neurodevelopmental assessmentWe analysed the scores in the neurodevelopmental assessment conducted at age 2 years (Bayley-III). The Bayley-III scales assess 5 developmental domains: cognition, language, social-emotional, motor and adaptive behaviour. It yields scores based on the answers or behaviour of the child that are transformed into scaled and composite scores for age. The results are scaled to a metric a mean of 100 points, and a standard deviation (SD) of 15 points and a range of 40–160 points. For each domain, values of less than 85 points are indicative of developmental delay and are classified as mild (1–2 SDs below mean), moderate (2–3 SDs below mean) and severe (<3 SDs below mean).

Data handling and analysisThe data were entered in an ad hoc database. The results were analysed and interpreted jointly by the research team and the research support unit of the hospital.

We described the characteristics of the sample using absolute frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables and the mean and SD or median and interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables.

Qualitative data were compared with the χ2 test or Fisher exact test, and quantitative data with the Kruskal-Wallis test. We assessed the association of variables with the Spearman correlation coefficient (r). We considered results with P values of less than 0.05 statistically significant. The statistical analysis was conducted with the software package Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC)

Ethical approval and consent to participationThe study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital on February 13, 2014 (PR (AMI) 317/2012). All pregnant women included in the study signed the informed consent form for participation in the study.

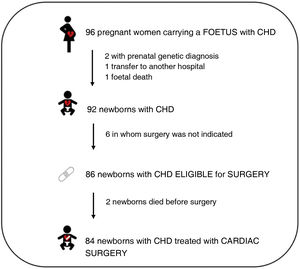

ResultsThe initial sample included 96 pregnant women carrying foetuses with a diagnosis of CHD. Four were excluded during pregnancy: 2 due to prenatal diagnosis of a genetic disorder, 1 due to foetal death and 1 due to transfer to a different hospital. In the 92 offspring of the remaining pregnant women, the diagnosis of CHD was confirmed after birth, and 86 were eligible for surgical management. Of these 86, 2 died before the surgery, and the 84 remaining infants who underwent surgery within 1 year of birth were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Table 1 presents the CHD diagnoses confirmed after birth. The most frequent form of CHD was transposition of the great arteries (TGA, 29 patients), followed by coarctation of the aorta with or without hypoplastic left heart (17 patients), tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia (16 patients) and atrioventricular septal defect (8 patients). Tables 2A and 2B present distribution of CHD cases into 4 groups based on anatomy and in 3 groups based on the degree of cyanosis.

Types of congenital heart disease.

| Disease | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| TGA | 29 | 34.5% |

| HLH-CoA | 17 | 20% |

| ToF/PA | 16 | 19% |

| AVSD | 8 | 9.5% |

| Other | 14 | 17% |

AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; CoA, coarctation of aorta; HLH, hypoplastic left heart; PA, pulmonary atresia; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; ToF, tetralogy of Fallot.

Classification of patients based on the anatomical and physiological characteristics of their congenital heart disease. Classification A: anatomy and physiology of CHD and presence of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction.

| Anatomy/physiology of heart defect | |

|---|---|

| Univentricular (UV) | Biventricular (BV) |

| 17 (20%) | 67 (80%) |

| Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 6 (35%) | 11 (65%) | 14 (20.9%) | 53 (79.1%) |

2 Classification of patients based on the anatomical and physiological characteristics of their congenital heart disease. Classification B: physiological classification based on the degree of cyanosis.

| Degree of cyanosis of the heart defect | ||

|---|---|---|

| None | Moderate | Severe (TGA) |

| 32 (38.1%) | 23 (27.4%) | 29 (34.5%) |

TGA, transposition of the great arteries.

Table 3 presents the results for the overall sample and by CHD anatomy group.

Characteristics of the patients by anatomical group.

| Variable | Heart disease group | Total | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univentricular | Biventricular | |||||

| Without SO | With SO | Without SO | With SO | |||

| Total | 11 | 6 | 53 | 14 | 84 | |

| Sex: male | 54.5% | 66.7% | 54.7% | 28.6% | 51.2% | .2995* |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38 (37−39) | 38.5 (37−40) | 39 (38−40) | 39.5 (38−40) | 39 (38−40) | .0880** |

| Preterm birth | 0 | 0 | 9.4% | 7.1% | 7.1% | .8891* |

| Weight (g) | 3250 (2900−3380) | 3095 (2780−3650) | 2920 (2700−3400) | 3130 (2920−3520) | 2997.50 (2760−3480) | .5808** |

| Head circumference (cm) | 34 (33−34.5) | 33.5 (33−34) | 33.5 (33−34.5) | 34.25 (33−36) | 34 (33−34.5) | .3448** |

| Neonatal surgery | 54.55% | 100% | 62.26% | 92.3% | 69.1% | .0502* |

| Age at time of surgery (days) | 31 (18−182) | 9 (8−15) | 14 (7−158) | 12 (7−24) | 14 (8−130) | .0116** |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 25 (8−35) | 38.5 (23−60) | 16 (9−24) | 25 (11−38) | 19 (9−29.5) | .040** |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 27 (23−50) | 56.5 (23−64) | 26 (17−36) | 41.5 (26−48) | 27.5 (18.5−46) | .2029** |

| Aristotle score | 7 (6−9) | 10.75 (6−14.5) | 10 (8−10) | 8 (8−10) | 9 (7−10) | .0970** |

| High STAT score (≥4) | 63.6% | 83.3% | 22.6% | 28.6% | 33.3% | .0025* |

| Minutes of ECC | 46 (0−96) | 69.5 (0−137) | 141 (108−165) | 92.5 (0−143) | 129.5 (67.5−159.5) | .0025** |

| Prolonged ECC (>150 min) | 9.1% | 16.7% | 39.6% | 21.4% | 30.1% | .1624* |

| Maximal VIS at 24 h | 15 (8−19) | 61.5 (20−66) | 20 (11−32.5) | 17 (5−27) | 19 (10−32) | .0102** |

| High maximal VIS at 24 h (>20) | 18.2% | 66.67% | 49.1% | 28.6% | 42.9% | .1086* |

| PRISM III at 24 h | 9.5 (5−11) | 12 (3−22) | 10 (7−14) | 7 (4−16) | 10 (7−14) | .4169** |

| High PRISM III at 24 h (>20) | 0% | 33.3% | 1.9% | 0% | 3.6% | .0338* |

| Mechanical ventilation (days) | 2 (1−4) | 6 (2−12) | 3 (2−4) | 3 (2−5) | 3 (2−5) | .3893** |

| Confirmed/suspected genetic diagnosis | 36.4% | 0 | 7.6% | 14.3% | 12% | .0640* |

Qualitative variables expressed as relative frequencies (%), quantitative variables as median (IQR).

ECC, extracorporeal circulation; ICU, intensive care unit; PRISM, Pediatric Risk Of Mortality score; SO, systemic obstruction; STAT, Society of Thoracic Surgeons-European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery; VIS, vasoactive-inotropic score.

Six patients (7.1% of the total) were born preterm, and all had a biventricular anatomy. There were no differences in the sex distribution, mean gestational age, weight or head circumference between the groups of patients classified according to heart anatomy. Most patients (69.1%) were operated within 28 days post birth.

In the group with univentricular anatomy, a higher proportions of patients required vasoactive drugs or postoperative ECMO (11.8% vs 0%) and the mortality was higher (29% vs 0%), and the subset with SO had significantly longer stays in the ICU (38.5 days [23−60] vs 19 days [9−29.5]; P = .04), increased need of vasoactive support (maximal VIS, 61.5 [20−66] vs 19 [10–32]; P = .01), with a higher proportion requiring ECMO after surgery (16.7% vs 2.4%; P = .04) and a higher mortality (66.67% vs 5.95%; P < .01) (Table 2). Ten patients (12% of the total) received a genetic syndrome diagnosis after birth, either confirmed or highly suspected and awaiting confirmation.

Complications and acute neurologic eventsThe general complications and the ANEs developed by the patients are presented in Tables 4 (entire cohort) and 5 (by CHD anatomy group). We found no differences between groups in the variables under study, except for the use of insulin for management of hyperglycaemia, which was more frequent in the group with biventricular anatomy without SO.

General (non-neurologic) complications after surgery.

| General complications | Heart disease group | Total | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV without SO | UV with SO | BV without SO | BV with SO | |||

| Total included | 11 | 6 | 53 | 14 | 84 | |

| Arrhythmia | 36.4% | 50% | 54.7% | 42.9% | 50% | .6710* |

| Permanent pacemaker | 9.1% | 0 | 1.9% | 7.1% | 3.6% | .3987* |

| Withdrawal symptoms | 45.4% | 50% | 45.3% | 50% | 46.4% | .9815* |

| Paralysed diaphragm | 0 | 0 | 11.3% | 0 | 7.2% | .5577* |

| Hyperglycaemia requiring insulin | 18.2% | 33.3% | 79.3% | 35.7% | 60.7% | <.0001* |

| Survivor of cardiac arrest | 0 | 33.3% | 7.6% | 0 | 7.1% | .0950* |

| VAD/ECMO | 9.1% | 16.7% | 0% | 0% | 2.4% | .0390* |

| Postoperative death | 9.09% | 66.67% | 0% | 0% | 5.95% | .0001* |

Qualitative variables expressed as frequencies.

BV, biventricular; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; SO, systemic obstruction; UV, univentricular; VAD, ventricular assist device.

Acute neurologic events and epilepsy: outcomes in overall sample and by heart anatomy group.

| Complication | Heart disease group | Total | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV without SO | UV with SO | BV without SO | BV with SO | |||

| ANE | 9.1% | 16.7% | 13.2% | 14.3% | 15.4% | .8231* |

| Type of ANE | ||||||

| Arterial stroke | 0 | 0 | 3.8% (2) | 14.3% (2) | 4.8% | .6368* |

| Isolated GS central stroke | 0 | 0 | 3.8% (2) | 0 | 2.4% | |

| Venous thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 1.9% (1) | 0 | 1.2% | |

| Haemorrhage | 9.1% (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.2% | |

| Brain death | 0 | 16.7% (1) | 0 | 0 | 1.2% | |

| Epileptic seizures | 9.1% (1) | 0 | 3.8% (2) | 7.1% (1) | 4.8% | |

| ANE (excluding seizures) | 9.1% | 16.7% | 9.3% | 14.3% | 12% | .6368* |

| Time to event in presence of lesiona | ||||||

| Before surgery | 0 | 0 | 7.1% (1) | 1.2% | <.001* | |

| After surgery | 100% (1) | 100% (1) | 100% (5) | 92.3% (1) | 98.8% | |

| Epilepsy/need of AED post surgery (5) | 0 | 0 | 5.7% (4) | 7.1% (1) | 6% | .8672* |

Qualitative variables expressed as relative frequencies (absolute frequency in parentheses).

AED, antiepileptic drug; ANE, acute neurologic event; BV, biventricular; SO, systemic obstruction; UV, univentricular.

The postoperative mortality was 5.9%, corresponding to 5 patients, all of who had univentricular anatomy, and 4 of who had SO.

As regards the neurologic complications detected in the cohort, 13 ANEs were detected in the cohort. Two of them were diagnosed in 2 different patients before surgery.

Eleven ANEs were diagnosed after surgery in 9 patients: 5 ischaemic strokes, 3 episodes of seizures, 1 venous sinus thrombosis, 1episode of severe extra-axial haemorrhage and 1 case of severe hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy resulting in brain death). Of the 9 patients that experienced postoperative ANEs (10.7%), 6 were operated in the neonatal period (9.5 days [7.5–12.5]) and 1 at 36 days post birth.

There were no differences in the incidence of ANE between anatomical groups; on the other hand, postoperative ANEs were more frequent in the moderate cyanosis group (26.1% vs 10.7%; P = .04). Two patients who experienced ANEs died.

During the follow-up, 5 patients required antiepileptic drugs, 3 experienced postoperative ischaemic strokes and 1 was diagnosed with a genetic syndrome characterised by heart disease, epilepsy and neurodevelopmental delay. All 5 had a biventricular anatomy.

The incidence of ANEs was higher patients who required ECMO after surgery compared to all other patients (100% vs 9.76%; P = .01), and both of these patients died.

Of the patients that experienced and survived cardiac arrest in the postoperative period (n = 6), 3 had ANEs and 1 died from the neurologic complication.

The incidence of ANE was greater in patients with moderate cyanosis (no TGA), patients who required ECMO after surgery and patients who had cardiac arrest in the immediate postoperative period. We did not find significant differences in incidence based on gestational age, birth weight or head circumference, a high STAT score, the minutes of ECC, the maximal VIS at 24 h, the Pediatric Risk of Mortality score (PRISM III) or other variables.

Biomarkers of brain injuryIn the analysis of the levels of the two biomarkers, we found detectable levels in cord blood (S100B, 48.27 [16.89–171.12]; NSE, 0.46 [0.42−0.53]). The levels of S100B increased after surgery compared to the preoperative period, with greater values in the immediate postoperative period and a decreasing trend observed by 24 h after surgery (136.19 [72.68−211.14] vs 169.90 [67.5–284.07] vs 162.75 [62.12−278.10]; P ≤ .01). The levels of NSE did not increase after surgery compared to before (0.88 [0.73−1.06] vs 0.86 [0.70−0.98] vs 0.62 [0.54−0.86]; P = .241).

The levels of the biomarkers at the different time points by CHD group can be found in Table 6. Levels of S100B increased significantly in the immediate postoperative period in patients with SO (in both the BV and UV groups). We did not find significant differences at the other perioperative time points or between the other CHD categories.

Biomarker levels at different time points in relation to the type of heart disease.

| Markers | Heart disease group (anatomy) | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univentricular | Biventricular | |||

| S100B PRE | 175.11 (45.05−211.14) | 128.60 (76.81−224.67) | 136.19 (72.68−211.14) | .8692** |

| S100B POST1 | 217.05 (37.81−284.07) | 164.54 (67.50−298.36) | 169.90 (67.50−284.07) | .9193** |

| S100B POST2 | 172.78 (7.17;248.70) | 162.01 (62.12−350.13) | 162.75 (62.12−278.10) | .5995** |

| NSE PRE | 0.93 (0.83−0.97) | 0.86 (0.73−1.06) | 0.88 (0.73−1.06) | .5854** |

| NSE POST1 | 0.83 (0.70−0.95) | 0.88 (0.69−0.99) | 0.86 (0.70−0.98) | .6384** |

| NSE POST2 | 0.68 (0.56−0.91) | 0.62 (0.50−0.83) | 0.62 (0.54−0.86) | .3246** |

| Markers | UV without SO | UV with SO | BV without SO | BV with SO | Total | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S100B PRE | 128.76 (9.57−211.14) | 196.80 (118.92−247.53) | 130.19 (85.38−210.97) | 127.02 (63.81−257.87) | 136.19 (72.68−211.14) | .8311* |

| S100B POST1 | 73.55 (6.71−217.05) | 284.07 (258.11−341.29) | 131.06 (54.77−245.17) | 207.08 (138.29−406.03) | 169.9 (67.50−284.07) | .0537** |

| S100B POST2 | 68.54 (4.53−154.53) | 248.7 (196.0−296.72) | 161.34 (62.12−275.54) | 214.55 (113.06−395.99) | 162.75 (62.12−278.10) | .0996* |

| NSE PRE | 0.88 (0.72−0.95) | 0.95 (0.89−1.06) | 0.84 (0.73−1.08) | 0.90 (0.77−1.02) | 0.88 (0.73−1.06) | .8231* |

| NSE POST1 | 0.81 (0.70−0.95) | 0.84 (0.76−0.86) | 0.88 (0.69−1.06) | 0.87 (0.66−0.95) | 0.86 (0.70−0.98) | .7784** |

| NSE POST2 | 0.71 (0.54−0.90) | 0.68 (0.59−0.91) | 0.61 (0.51−0.82) | 0.62 (0.42−0.87) | 0.62 (0.54−0.86) | .7915** |

| Markers | Heart disease group (degree of cyanosis) | Total | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No cyanosis | Moderate cyanosis | TGA cyanosis | |||

| S100B PRE | 151.12 (80.95−248.08) | 130.19 (45.05−238.36) | 104.03 (72.45−189.77) | 136.19 (72.68−211.14) | .6783* |

| S100B POST1 | 87.60 (40.49−217.05) | 231.64 (37.81−353.51) | 164.54 (105.64−298.36) | 169.90 (67.50−284.07) | .4274* |

| S100B POST2 | 154.53 (22.32−266.06) | 184.39 (6.04−320.92) | 162.01 (107.05−264.04) | 162.75 (62.12−278.10) | .8446* |

| NSE PRE | 0.86 (0.64−1.02) | 0.93 (0.83−1.09) | 0.84 (0.73−1.06) | 0.88 (0.73−1.06) | .4432* |

| NSE POST1 | 0.74 (0.61−0.94) | 0.84 (0.75−0.99) | 0.90 (0.78−1.06) | 0.86 (0.70−0.98) | .0729* |

| NSE POST2 | 0.56 (0.40−0.71) | 0.65 (0.55−0.92) | 0.65 (0.58−0.84) | 0.62 (0.54−0.86) | .0772* |

Median (IQR).

BV, biventricular; NSE, neuron-specific enolase; PRE, immediately before surgery; POST1, immediately after surgery; POST2, 24 h after admission to ICU following surgery; SO, systemic obstruction; S100B, S100 calcium-binding protein B; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; UV, univentricular.

The levels of S100B were higher in the immediate postoperative period in patients that experience ANEs after surgery compared to patients who did not (284.07 [167.74–483.50] vs 164.54 [67.50–273.01]; P = .20), but the difference was not statistically significant; the levels of NSE were similar in patients who had ANEs and the rest of the patients (0.75 [0.75−0.76]) vs 0.87 [0.70−0.98]; P = .578).

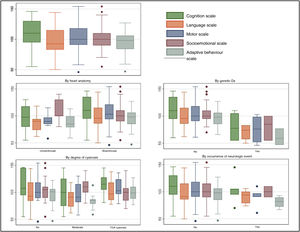

Long-term follow-upFive of the 84 patients died during the follow-up, and another 5 were lost to follow-up. Of the 74 remaining patients, 55 (74%) were evaluated at 2 years with the Bayley-III. The median scores in each of the 5 domains of the test were all within the normal range (85−115) (Fig. 2).

Thirty-eight patients had normal scores (≥ 85) in the cognition, motor and language domains; 30 had normal scores in every domain in the test. Of the patients who had an abnormal score in at least one domain, 16 had a low score in only one domain. There were 9 patients with scores below the normal range in 2 or more domains. Of the 6 patients with abnormal scores in 3 or more domains, 4 had neonatal cyanosis of moderate or high degree, 2 had UV anatomy, and 1 who had abnormal scores in all 5 domains had been diagnosed with a genetic syndrome associated with abnormal neurodevelopment.

We obtained a total of 260 scores for the assessed domains in the 55 patients (all patients underwent assessment of at least 3 domains and up to a total possible maximum of 5); 43 of the 260 scores were below the normal range, of which 27 indicated mild delay, 13 moderate delay and 3 severe delay.

Patients with UV anatomy scored lower in the cognition, motor, language and adaptive behaviour domains, and the difference was statistically significant in the motor assessment (89.5 [85–97] vs 103 [94–121]; P = .02).

We did not find significant differences when we compared the scores of patients based on the degree of cyanosis (Fig. 2).

Patients who experienced an ANE had scores lower than normal in at least 1 domain of the Bayley-III (2 of these patients had low scores in 3 or more domains), although the differences compared to patients without ANEs were not statistically significant: cognition (95 [81–105] vs 110 [95–130]; P = .5; language (79 [78–94] vs 91 [86–115]; P = .5); motor (91 [85–91] vs 100 [91–118]; P = .13); socioemotional (100 [90–110] vs 100 [90–115]; P = .8) and adaptive behaviour (82 [75−25; 89.25] vs 98 [85–106]; P = .07), as can be seen in Fig. 2.

Patients with epilepsy had significantly lower scores in the motor assessment (100 [91–118] vs 53.5 [46–61]; P = .02).

Patients who survived an episode of cardiac arrest after surgery had lower scores compared to patients who did not experience cardiac arrest in 4 of the 5 domains: cognition (82.5 [67.5–101.25] vs 110 [97.5–1032.25]; P ≤ .01), language (82.5 [77.75–88] vs 95.5 [86–115]; P ≤ .01); motor (89.5 [81.25–100] vs 100 [92.5−118]; P ≤ .01) and adaptive behaviour (76.5 [71.75–81.25] vs 98 [85–106]; P ≤ .01).

Patients with a suspected or confirmed genetic disorder scored lower in all domains, with significantly lower scores in the language, motor and adaptive behaviour domains. The scores in this group were the following, compared to those of patients without a genetic diagnosis: language, 74 [57.5–83] vs 92.5 [83–115] (P = .006); motor, 76 [52–98.6] vs 100 [91–118] (P = .0057); adaptive behaviour, 59 [47–77] vs 98 [84–106] (P = .007); cognition, 77.5 [55–105] vs 110 [95–130] (P = .051); socioemotional, 85 [55–100] vs 100 [90–110] (P = .069).

Excluding the patients with genetic syndromes from the analysis, 21 patients had scores below 85 in at least one domain, with 15 scoring low in one domain, 2 in two domains and 4 in three domains. Nine patients had language delay (mild in 7, moderate in 2), 9 had delays in adaptive behaviour (mild in 5, moderate in 4), 5 cognitive delay (mild in all), 4 delay in socioemotional development (mild in all) and 3 in motor development (mild in 2, moderate in 1).

We analysed the correlation between the measured levels of the markers of brain injury at each time point and the scores of the patients in the different domains of the Bayley-III. There was a correlation between higher levels of S100B in the immediate postoperative period and lower scores in the domains of cognition (r = 0.336 [0.023−0.589]; P = .036), language (r = 0.337 [0.020−0.593]; P = .038) and motor development (r = 0.424 [0.125−0.652]; P ≤ .01). We did not find a correlation between the level of NSE at the different perioperative time points and the scores in the Bayley-III domains.

Thus, we found less favourable scores in the Bayley-III in patients who experienced ANEs in the postoperative period, although the difference with the scores of patients without ANEs was not statistically significant. In our cohort, patients with CHD operated in the first year of life had lower scores in the Bayley-III scales if they had a univentricular cardiac anatomy, received a diagnosis of genetic disorder, suffered and survived cardiac arrest in the postoperative period and had elevated levels of S100B in the immediate postoperative period.

DiscussionIn the studied cohort of newborns with CHD managed with cardiac surgery and followed up from the foetal period, we found that at age 2 years, more than half of assessed patients had normal overall neurodevelopmental outcomes, which was consistet with the recent literature.11–14 However, 45.4% of the patients had scores of less than 85 in at least one of the five domains of the Bayley-III scales and 31% have low scores in the cognition, language or motor domains. In addition, 34.5% of the total had abnormal scores in 1 or 2 neurodevelopmental domains and 10.9% in 3 or more domains.

It is estimated that 30%–50% of patients with complex CHD exhibit neurodevelopmental abnormalities ranging from mild cognitive delay to severe executive dysfunction.2,8,15 At present, learning difficulties are the most prevalent heath problem in school-aged patients with CHD.2,11,16–19

In our study, all patients who died after surgery had UV anatomy and 80% had LFOT. Consistent with the previous literature, postoperative severity (measured with the PRISM-III risk of mortality score) was greater in patients with UV anatomy, who had longer lengths of stay and had a greater need for vasoactive support and ECMO compared to the rest of the sample.16,20,21

Patients with UV anatomy had lower scores in the Bayley-III scales; specifically, they had poorer scores compared to the rest of the patients in the cognitive, language, motor and adaptive behaviour assessments. On the other hand, we did not find statistically significant differences based on the degree of cyanosis.

In our cohort, newborns with a genetic syndrome diagnosis had lower scores in the Bayley-III scales, as previously reported.6,22,23 Although there is solid evidence supporting the inclusion of genetic testing in routine management protocols, it is not routinely performed in our region.15

Patients with postoperative ANEs had lower scores in the cognition, motor and adaptive behaviour domains, as previously described,24–29 although in our cohort these differences were not statistically significant. Younger age at the time of surgery was associated with an increased risk of ANE, and cardiac arrest after surgery was associated with an increased mortality and poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The analysis of biomarkers of brain injury revealed an increase in the levels of S100B in the immediate postoperative period, as reported in other case series,7,8,30,31 although in our study, this increase was not significantly associated with the probability of ANEs after surgery.

Elevation of S100B levels in adults has been associated with stroke, an increase in mortality and in length of stay, delirium, poorer neuropsychiatric outcomes and memory impairment after cardiac surgery.32,33 In the paediatric population, elevation of S100B has been observed in patients with neurologic complications managed with ECMO,34 after extracorporeal surgery31 and in the context of perinatal asphyxia or head trauma with intracranial lesions.32

In the correlation analysis, higher levels of S100B in the immediate postoperative period appeared to be associated with poorer scores in the cognition, language and motor domains of the Bayley-III scales at age 2 years. The evidence on the predictive value of S100B in the paediatric population is scarce compared to the adult population, but we did find studies that found a correlation between higher values of S100B after head trauma and poor neurologic outcomes35 and higher values of S100B after cardiac surgery in patients with CHD and poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes.8,30

In our cohort, the levels of NSE did not increase after surgery, contrary to what has been observed in other case series.7,30,31,33 In adults who underwent coronary bypass surgery and after cardiac arrest, NSE is a reliable predictor of adverse neurologic outcomes,36 in the paediatric age group, it has been found useful as a marker of brain injury in samples of cerebrospinal fluid from newborns with hypoxic/ischaemic encephalopathy managed with hypothermia.37 In our study, we did not find an association of NSE with postoperative ANEs or poorer early neurodevelopmental outcomes.

LimitationsThe small size of some of the subgroups, especially the UV group, and the mortality within this subgroup, have affected the overall neurodevelopmental assessment results, although this has also reflected the greater medical complexity of this type of defects.

We conducted a descriptive analysis due to the small number of patients in some of the subgroups, which did not allow performance of a multivariate analysis free of bias, and we expect to be able to carry out such an analysis in future studies conducted in larger samples.

Neurodevelopmental disorders evolve through time, and some develop at older ages and cannot be detected in early neurodevelopmental assessments. Patients with operated CHD need to remain in follow-up and undergo neurodevelopmental assessments at older ages to ensure detection of potential abnormalities.

ConclusionAlthough the average scores in the neurodevelopmental assessment at age 2 years of patients with a prenatal diagnosis of CHD who underwent surgical repair in the first year of life were within the normal range, one in three patients had abnormal results in the motor, language and cognition assessments.

In our study, patients with genetic disorders and patients with univentricular heart anatomy had poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 2 years compared to the rest of the cohort. Acute neurologic events during the postoperative period could contribute to poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 2 years.

In this cohort, the highest levels of S100B in the immediate postoperative period occurred in patients with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 2 years. Further research is needed to elucidate the value of postoperative S100B levels for prediction of unfavourable neurodevelopmental outcomes in patients with complex CHD.

The early identification of genetic syndromes and postoperative ANEs and the delivery of standardised and personalised care for infants with univentricular CHD are important to improve long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The neurobehavioural follow-up of patients with CHD should be standardised to progress toward an integrative care model aimed at promoting healthy development and improve quality of life in these patients and their families.

FundingThe study was partially funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III through research grants for projects PI13/01449 (Impact of congenital heart diseases on the development of the central nervous system: pre- and postnatal factors associated with early neurodevelopmental outcomes) and PI17/02198 (Usefulness of integrative neuromonitoring for prediction of neurodevelopmental outcomes in patients subjected to cardiac surgery in the paediatric age: from the clinic to the paediatric animal model).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank the Statistics and Bioinformatics Unit of the Vall d’Hebrón Institut de Recerca, and its head, Dr Santiago Pérez-Hoyos, in particular, for their collaboration in the analysis and interpretation of the study results, and the Department of Bioinformatics and Clinical Pharmacology of the Hospital Universitari Vall Hebrón for their contribution to the study design and the maintenance of the study database.

Previous presentation: partial results from this study were presented at the XXVII Congress of Neonatology and Perinatal Medicine/VII Congress of Neonatal nursing held October 2−4, 2019 in Madrid, Spain.