Non-bacterial chronic osteomyelitis (NBCO) is an autoinflammatory disease that presents with recurrent bouts of bone inflammation in the absence of microbiological isolation. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. Its treatment was classically based on the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids, although nowadays bisphosphonates or anti-tumour necrosis factor-α (anti-TNF) drugs are frequently used with good results. The objective of the study is to describe our experience in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with NBCO.

Patients and methodsRetrospective chart review of patients with NBCO followed up in a tertiary centre between 2008 and 2015.

ResultsA total of 7 patients with NBCO were recorded. Four were female and the median age was 10 years (IQR 2). The most common complaint was pain that interfered with sleep in 5 of the patients. Six patients had multifocal lesions at diagnosis. Bone biopsy demonstrated neutrophilic or lymphocytic infiltration and sclerosis in 6 patients. Four patients received antibiotics and NSAIDs without clinical response. Five received a short course of prednisone with an adequate control of symptoms, but only one of them maintained remission after corticosteroid suspension. Five patients received bisphosphonates with disease remission in 3 of them. The other 2 showed an inadequate response to pamidronate and were started on anti-TNF therapy (etanercept, infliximab or adalimumab), remaining asymptomatic at present.

ConclusionsOur series, although limited, confirms the effectiveness and safety of bisphosphonate and anti-TNF therapy for children with NBCO.

La osteítis crónica no bacteriana (OCNB) es una enfermedad autoinflamatoria que cursa con brotes de inflamación ósea en ausencia de aislamiento microbiológico. Su diagnóstico es de exclusión. El tratamiento se basaba en la utilización de antiinflamatorios no esteroideos (AINE) y esteroideos aunque cada vez con mayor frecuencia se utilizan bifosfonatos o fármacos contra el factor de necrosis tumoral α (anti-TNFα) con buenos resultados. El objetivo es revisar nuestra experiencia en el diagnóstico y tratamiento de estos pacientes.

Pacientes y métodosRevisión retrospectiva de las historias clínicas de los pacientes diagnosticados de OCNB entre 2008 y 2015 en un hospital terciario.

ResultadosDe un total de 7 pacientes, 4 eran mujeres, con una mediana de edad de 10 años (RIQ 2). El motivo más frecuente de consulta fue dolor que interfería con el sueño en 5 pacientes. Seis presentaron lesiones multifocales al diagnóstico. En 6 se realizó biopsia ósea que demostró un infiltrado neutrofílico o linfocitario y esclerosis. Cuatro pacientes recibieron tratamiento antibiótico y AINE sin respuesta clínica. Cinco pacientes recibieron prednisona, consiguiéndose control sintomático que solo mantuvo uno tras su suspensión. Cinco recibieron bifosfonatos con remisión de la enfermedad en 3. Dos pacientes presentaron una respuesta insuficiente a pamidronato, por lo que recibieron terapia anti-TNFα (etanercept, infliximab o adalimumab) y se mantienen asintomáticos en la actualidad.

ConclusionesNuestra serie, aunque limitada, confirma la efectividad y seguridad de la terapia con bifosfonatos y fármacos biológicos en pacientes con OCNB.

Nonbacterial chronic osteomyelitis (NBCO), also known as chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, is an autoinflammatory disease characterised by bouts of bone inflammation in the absence of microbiological isolation. It presents with bone pain, usually to finger pressure, that may or may not be associated with inflammation of the skin and adjacent tissues. Up to 20% of cases are unifocal at the time of diagnosis, which requires a differential diagnosis including bacterial osteomyelitis, trauma, and malignant diseases. When the lesions are multifocal they are usually symmetrical and predominantly affect the metaphyses of the long bones of the lower limbs, but may also involve the pelvis, spine and clavicle. Fever is an uncommon symptom, although patients may develop low-grade fever. The pain can be severe and disabling, and may be associated with functional impairment. This is an infrequent disease of unknown incidence and prevalence that is probably underdiagnosed.1,2

The disease is found worldwide, although most of the published case series are from developed countries in Europe, North America and Australia, probably due to their superior diagnostic and therapeutic resources.

The disease is variable in its presentation and clinical course and is a diagnosis of exclusion, so delays in diagnosis are frequent. The abnormal laboratory results that may be associated to it are nonspecific. When they occur, they correspond to signs of systemic inflammation such as anaemia of chronic disease, leukocytosis or elevated acute phase reactants. The literature has described varying degrees of correlation with the histocompatibility agent HLA-B27 (7–21%), which in turn stems from the association of NBCO to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and sacroiliitis.3,4 Since the clinical presentation and imaging findings in NBCO may be nonspecific, cases with unifocal lesions require performance of a bone biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.1

Traditionally, treatment was initiated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), although we now know that this does not achieve adequate symptom control in a high percentage of cases.5 In the past decade, biphosphonate therapy has risen as the first step in its management, as it not only controls pain, but also induces remission in some cases.6 Other alternative treatments are based on new developments in molecular biology, which have allowed the detection of the local and systemic elevation of different cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα)7 or interleukin 1 (IL-1).8 The inhibition of these molecules, mainly by means of anti-TNFα drugs, has shown promising results.9,10

The aim of this study was to review our experience in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with NBCO.

Patients and methodsWe reviewed the medical records of all patients diagnosed with NBCO that (1) met the inclusion criteria detailed below and (2) were being followed up in the Paediatric Rheumatology clinic of our hospital between April 1, 2008 and March 31, 2015. We collected relevant clinical, laboratory, radiology and outcome data, which are presented in Table 1.

Clinical features, laboratory findings and imaging tests in six paediatric patients with NBCO.

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ♂ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♂ | ♀ | ♂ |

| Age of onset (years) | 10 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 11 |

| Delay in diagnosis (months) | 7 | 3 | 24 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Clinical presentation | |||||||

| Fever | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| Bone pain | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Bone/soft tissue swelling | + | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| Skin lesions | − | Pustulosis palmoplantar | Acne vulgaris | Pustulosis palmoplantar | − | − | − |

| Functional disability | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Other | − | Anorexia/weight loss | − | − | Asthenia/weight loss | Weight loss/sweating | |

| Autoimmune diseases | Crohn's disease | Psoriasis | − | − | − | Psoriasis | − |

| Family history | − | Rheumatoid arthritis | − | − | − | − | − |

| Laboratory tests | |||||||

| Immunochemistry | |||||||

| ANA and Ig | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Acute phase reactants (at diagnosis) | |||||||

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1.22 | 2.15 | 0.07 | 3.95 | 2.31 | + | + |

| ESR (mm/h) | 96 | 6 | 8 | 79 | 70 | + | + |

| Diagnosis | |||||||

| (Imaging/biopsy) | Biopsy | Biopsy | Biopsy | Imaging | Biopsy | Biopsy | Biopsy |

| Imaging tests | XR, MRI, BSc | XR, MRI, BSc | XR, CT, BSc, MRI | XR, MRI, BSc | XR, MRI, BSc | XR, MRI, BSc | XR, RMN, BSc |

| Involved bones | |||||||

| Femur | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Tibia/fibula | + | − | + | + | − | + | − |

| Vertebrae | − | + | − | + | + | + | − |

| Pelvis | − | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| Radio/ulna | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Clavicle | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Other | Rib shaft/scapula | Tarsus | Ribs | Calcaneus, sternum, skull | Ribs | ||

| Number of lesions at diagnosis | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Total number of lesions | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 3 |

| Distribution of bone lesions | Multifocal | Multifocal | Unifocal | Multifocal | Multifocal | Multifocal | Multifocal |

| Symmetry of ≥1 lesion | + | + | − | − | + | − | + |

| Treatment | |||||||

| 1. Antibiotics/response | Cloxacillin-Cefotaxime/no | Azithromycin/no | Penicillin-Clindamycin/no | No/− | No/− | No/− | Yes/no |

| 2. NSAIDs/response | Yes/yes | Yes/no | Yes/no | Yes/no | Yes/no | Yes/no | Yes/no |

| 3. Corticosteroids/response | Lost to followup | Prednisone/partial | No/− | Prednisone/yes | Prednisone/partial | Prednisone/partial | Prednisone/partial |

| 4. Biphosphonates/response | Lost to followup | Pamidronate/yes | Pamidronate/yes | No/− | Pamidronate/partial | Alendronate/partial Pamidronate/partial | Alendronate/partial Pamidronate/yes |

| 5. Anti-TNF/response | Lost to followup | No/− | No/− | No/− | Etanercept/partial Infliximab/− | Adalimumab/partial Infliximab/yes | No/− |

| Relapses | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

BSc: bone scintigraphy; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; XR: X-ray; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; Ig: Immunoglobulin; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) NBCO diagnosis and (2) age of onset of less than 16 years.

The diagnosis of NBCO was made based on the clinical presentation and imaging findings. A bone biopsy was performed in six out of the seven patients.

We conducted a descriptive analysis, expressing continuous variables (age of onset and length of diagnostic delay) as median and interquartile range (IQR) and qualitative variables as absolute frequencies and percentages.

ResultsTable 1 presents the distribution of the patients by age, sex, delay in diagnosis, symptoms at onset, diagnostic tests, imaging tests, and treatment.

Of the seven patients included in the study, four were female and three were male. The median age of onset was 10 years (IQR, 2), with a median delay in diagnosis of seven months (IQR, 10).

Patient 2 was the only one with a family history of autoimmune disease (rheumatoid arthritis in the maternal grandmother). Three patients received a diagnosis of autoimmune disease during the followup, two of psoriasis (patients 2 and 6), and one of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (patient 1).

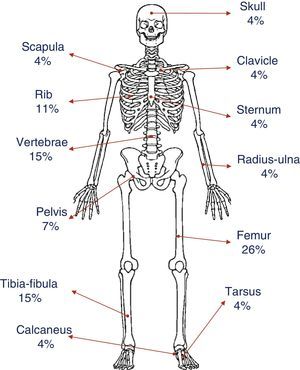

The most common presenting complaint was pain, usually continuous tenderness to finger pressure in some of the sites of osteitis (patients 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7) that interfered both with sleep (patients 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7) and with walking (patients 2, 4, 5 and 6). All patients except patient 3 presented with multifocal lesions at the time of diagnosis. The only presenting symptom in patient 3 at the time of diagnosis was a hard mass in the right fibula that was painful on palpation. Fig. 1 shows the distribution and percentages of the lesions in all of the patients. The most frequently involved bone was the femur (6/7), both at the distal and proximal levels, followed by the tibia, fibula and vertebrae, especially the lumbosacral region (4/7). The pelvis and several ribs were involved in four patients. Other less frequent locations were the clavicle, sternum, radius, ulna, calcaneus and tarsus.

When it came to extraosseous manifestations, three patients had fever, usually low-grade, three had a constitutional syndrome with asthenia and weight loss, and four experienced cutaneous manifestations (patients 2 and 4, palmoplantar pustulosis; patient 3, acne vulgaris; and patient 6, psoriasis). Patient 6 also developed Achilles enthesitis during the course of the disease. The findings of the physical examination were otherwise normal in all patients.

Laboratory values exhibited a high variability, with the presence of anaemia and leukocytosis in one patient and elevation of acute phase reactants in six out of the seven patients. The immunoglobulin levels and autoimmunity screening (antinuclear antibodies) were normal in all patients. Determination of HLA-B27 was only performed in patient six, and the result was negative.

Imaging tests were performed in all patients (Table 1). Plain radiography revealed the presence of isolated lytic lesions in two patients: in the fibula in the girl with unifocal disease, and in the distal femur in patient 6. Bone scintigraphy was very helpful in the detection of clinically silent lesions (patients 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7), allowing a more precise investigation with targeted MRI.

Six patients underwent a bone biopsy, which revealed neutrophilic or lymphocytic infiltration and sclerosis. The possibility of neoplastic disease was only considered in the unifocal lesion case (patient 3). Furthermore, the bone biopsy in this patient led to the detection of Propionibacterium acnes by means of polymerase chain reaction, following negative results in the Gram stain and cultures. The cultures of lesion samples in all other patients were negative for bacteria (aerobic and anaerobic), mycobacteria and fungi.

Four patients that were initially admitted to the department of infectious diseases were treated with antibiotics (penicillin, cloxacillin, cefotaxime, clindamycin and azithromycin) combined with NSAIDs at analgesic doses, and did not respond to treatment. Five patients received prednisone at doses of 1mg/kg/day for three weeks, followed by a slow tapering off for a total of eight weeks’ treatment; remission of symptoms was achieved in all cases, although it was only maintained in patient 4 after discontinuing medication. This patient remains asymptomatic to date, and the follow-up MRI six months after treatment completion did not find any lesions.

The other four patients and also patient 3 were treated with biphosphonates. Patients 6 and 7, who received the diagnosis before 2006, started treatment with oral alendronate and responded poorly, and were switched to intravenous pamidronate, achieving remission. Another patient in whom the diagnosis was made at a later date was given pamidronate as the first-line treatment from the beginning, and responded favourably. The biphosphonate regimens varied from patient to patient based on their response to treatment, with the dosage ranging from single doses of 30mg every three months to doses of 1mg/kg/day administered in three consecutive days on a monthly basis.

Two of the patients treated with pamidronate did not achieve adequate symptom control, so they were given anti-TNFα agents. The first one was patient 6, who had initially achieved symptom control with pamidronate and progressively lost response to treatment over the nine months that followed, leading to initiation of adalimumab. She achieved clinical remission, which lasted three years until she developed new symptoms that were controlled with infliximab, a treatment that she is still receiving today. The second was patient 5, who did not respond to etanercept and is currently being treated with infliximab.

DiscussionNon-bacterial chronic osteomyelitis is a heterogeneous disease both in its clinical presentation and its response to treatment, as our case series corroborates. It is more prevalent in females, and onset occurs most frequently at around 10 years of age. This disease is rarely found in individuals aged more than 20 years.2 The demographic characteristics of our patients were consistent with the literature on NBCO, both in the sex distribution and age of onset.

In up to one fourth of the cases, NBCO is associated to autoimmune diseases such as arthritis or sacroiliitis, psoriasis, or IBD. It has also been reported that up to 40% of patients have first- and second-degree relatives affected by autoinflammatory or autoimmune diseases.2 Our experience is also consistent with this, as we found a personal history of psoriasis or IBD or a family history of arthritis in some of our patients.

The main symptom of NBCO is bone pain, usually inflammatory, that interferes with sleep and associated with functional impairments, with or without fever or low-grade fever and systemic symptoms. The bone lesions are often silent and are only detected by imaging tests. Consequently, the diagnosis of NBCO should be considered in any patient with compatible symptoms, including those that present with various simultaneous foci of localised musculoskeletal pain or with a history of bone pain that changes location through time in the absence of a history of trauma.1,10,11

When it comes to diagnostic imaging, plain radiography is usually not helpful in the early stages of disease. Lytic lesions are only discernible when the loss of mineralisation has reached 30–50%, which occurs at different times from onset depending on the extent and activity of the disease. Hyperostosis and osteosclerosis can be observed in chronic lesions.12 Thus, the methods used for assessment are those that allow the determination of the extent of asymptomatic active lesions, such as bone scintigraphy with 99mTc, which uses ionising radiation, or whole-body MRI. Conventional MRI with short time inversion recovery (STIR) sequences is the gold standard both for differential diagnosis of the lesions and for assessing response to treatment, as it does not expose patients to ionising radiation.1,13 All our patients underwent a bone scintigraphy to locate the lesions, followed by MRI to complete the diagnostic evaluation and monitoring the disease.

The combination of clinical features and imaging findings may suffice to diagnose the disease, especially in patients with multifocal lesions and manifestations of several months’ duration in whom diagnostic tests have ruled out malignant disease.1 In other cases, however, diagnosis requires a bone biopsy. This is most commonly needed in patients with unifocal lesions in whom malignancy could not be ruled out. In our series, all the biopsies performed in cases of multifocal disease corresponded to patients initially referred to the departments of traumatology or infectious diseases.

When it comes to treatment, we now know that antibiotherapy is not effective,5,14 although it used to be the first-line treatment in the past. Four of our patients were initially treated with antibiotics and none of them had improved after three weeks of therapy.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are considered the gold standard for first-line treatment, despite the heterogeneous results of the different studies in the literature.3,5,14–16 Schultz et al.14 reported that 79% of a sample of 190 patients responded to treatment with NSAIDs, but did not provide information on the duration of treatment or subsequent relapses. Girschick et al.3 reported that a subset of 18 patients with non-relapsing NBCO (single occurrence) achieved remission with naproxen six months after initiation of treatment, while naproxen alone was sufficient to achieve remission in only five out of twelve patients with recurrent NBCO, and ten of these patients required other treatments. These differences suggest that the response in the first group—single occurrence—may have been due to the natural history of the disease and not to the treatment with NSAIDs. In a prospective study conducted by Beck et al. in 37 patients,15 43% achieved a symptom-free status with NSAIDs, a rate that decreased to 27% when the definition of remission included the absence of inflammatory features in imaging tests. Many subsequent case series have demonstrated that NSAIDs do not achieve adequate control of pain or disease activity, and that additional treatments are required.9,11,15–17 In our experience, consistent with the latest published articles, 6 out of 7 patients with NBCO did not respond to naproxen. The seventh patient (patient 1) did respond to naproxen for four weeks and did not attend any of the scheduled followups thereafter, as the family refused to initiate any other treatment.

As for corticosteroids, their use seems to be effective at doses of 1–2mg/kg a day with progressive tapering off and a total duration of treatment of eight weeks.5,11,18 However, it is also true that in most of the recent case series that describe the usefulness of biphosphonates or TNFα antagonists, the patients had been previously treated with corticosteroids and had either had partial responses or relapses.9,15–17 This indicates that the effectiveness of systemic corticosteroids may be transitory, and maintaining their efficacy requires doses that are high enough to cause adverse effects over time. In our series, five patients were treated with oral prednisone, and four showed full clinical remission while the maximum dose was maintained, but, as noted above, they relapsed upon reducing the dose except for one girl (patient 4) that remained in remission six months after completing the course of treatment.

Biphosphonates provide a therapeutic alternative in patients who do not respond to NSAIDs or corticosteroid therapy. Their use is based on their potential anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects at the osseous level, which result from their antiresorptive activity. The use of intravenous pamidronate in patients with NBCO has become more widespread as its safety has been demonstrated by its use in other diseases, such as osteogenesis imperfecta and childhood osteoporosis.19,20 Several studies published in recent years show that biphosphonate therapy is effective in patients with NBCO and is associated with a rapid clinical response, with symptom improvement or remission as early as 3 days after the first intravenous dose that can be confirmed by imaging.21–30 Most of these studies document the efficacy of biphosphonates in the treatment of relapses in patients that had received previous treatment with these agents, without the severe adverse effects that have been described in adult patients (osteonecrosis of the jaw), although flu-like symptoms are frequently experienced with the first infusions. Five patients in our series were treated with biphosphonates. In patients 2, 3 and 7, the pain resolved after the first dose of pamidronate. Patient 4 experienced a partial clinical remission that allowed her to resume physical activity, but had a relapse on the fourth month with pain and elevation of acute phase reactants that led to initiation of anti-TNF therapy. This patient developed an intense flu-like syndrome with fever with peaks of up to 40°C with the first infusion of pamidronate. Another two (patients 2 and 3) developed low-grade fever and mild arthromyalgia with the first dose of the drug.

In the past ten years, biological therapy has started to be used successfully in children. In light of the pathophysiology of NBCO and the elevated levels of cytokines such as TNFα in these patients, several authors have used drugs against this biological target (infliximab, adalimumab and etanercept). They are used as rescue therapy after treatment with biphosphonates has failed. Overall, most of the cases described in the literature show clinical and imaging improvement that is maintained for up to 24 months after initiation of treatment.9,22,31–38 Two of our patients have required treatment with anti-TNFα agents. Patient 5 was treated with etanercept with a partial response, and is now receiving infliximab. In patient 6, treatment was initiated with adalimumab, with improvement of symptoms for a period of three years. Due to the development of new symptoms, treatment was switched to infliximab, which achieved adequate pain control with resolution of lesions in MRI to this date, after one year of treatment. All anti-TNFα agents carry an increased risk of infection. The development of psoriatic lesions has also been reported in the literature.9,34 In our patients, biological therapy has not been associated with any significant adverse events.

There are some limitations to our study, including its retrospective single-centre design and the small number of patients it includes. Nevertheless, its results are consistent with the most recent published evidence on the effectiveness and safety of biphosphonates and biological agents for controlling the disease.

The optimal approach to the management of NBCO remains unknown,39,40 and more prospective studies are required to compare different treatments and determine the long-term safety of biphosphonate use and biological therapy in children with NBCO.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare

Please cite this article as: Barral Mena E, Freire Gómez X, Enríquez Merayo E, Casado Picón R, Bello Gutierrez P, de Inocencio Arocena J. Osteomielitis crónica no bacteriana: experiencia en un hospital terciario. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;85:18–25.