Virtual visits (VVs) were used during the pandemic as an alternative to face-to-face visits. Following this experience, the implementation of this type of telemedicine in pediatric care may offer clear advantages and benefits, but it is important to understand the perspectives of both patients and caregivers.

Material and methodsCross-sectional descriptive with data collection through an online questionnaire distributed via QR code and hosted on REDCap completed anonymously by parents/legal guardians and adolescents (n = 426). We obtained data on sociodemographic characteristics, previous experience with telemedicine and the perceived usefulness of VVs from 316 caregivers and 110 adolescents. We analyzed the associations with demographic variables and performed comparative analyses.

ResultsBoth groups considered VVs a useful alternative, particularly when it came to primary care and hospital-based follow-up. Caregivers highlighted saving time (53%) and reducing school absenteeism (40%) as the main advantages, whereas adolescents emphasized reducing the environmental impact associated with the visit (48%). The ideal duration was estimated at 5–15 min, and more than 95% agreed that VVs should be offered as a voluntary option. We found a higher level of acceptance among caregivers who were younger, with higher educational attainment, who did not have a private vehicle or who had greater difficulty accessing the hospital. The main concern did not involve data breaches or aspects related to confidentiality (10%), but the possibility of missing the call and therefore the appointment (33%).

ConclusionsBoth patients and caregivers support the integration of VVs in pediatric care, provided they remain a voluntary and complementary alternative to in-person care. Future programs should consider user preferences, suggestions and the actual barriers they perceive.

Las visitas virtuales (VV) se utilizaron durante la pandemia como alternativa a las consultas presenciales. Tras esta experiencia, implementar este tipo de telemedicina en Pediatría, podría ofrecer ventajas y beneficios, pero es importante conocer la opinión de pacientes y cuidadores.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo transversal mediante encuesta online anónima, difundida por QR y alojada en REDCap, dirigida a padres-tutores y adolescentes (n = 426). Se recogieron datos sociodemográficos, experiencia con telemedicina y percepción sobre la utilidad de las VV de 326 cuidadores y 110 adolescentes. Se analizaron asociaciones con variables demográficas y análisis comparativos.

ResultadosAmbos grupos consideraron las VV una alternativa útil, especialmente en atención primaria y en seguimiento en atención hospitalaria. Los cuidadores priorizaron como principales ventajas el ahorro de tiempo (53%) y perder menos clase/colegio (40%); mientras que los adolescentes, destacaron la reducción de la contaminación (48%). La duración ideal estimada fue entre 5−15 minutos, y más del 95% opinó que deberían ofrecerse siempre como opción voluntaria. Se observó mayor aceptación en cuidadores más jóvenes, con estudios superiores, sin coche o con mayor dificultad para acceder al hospital. El principal temor no fue la pérdida de datos o temas relacionados con confidencialidad (10%), sino el no poder contestar la llamada y perder por eso la cita (33%).

ConclusionesTanto pacientes como cuidadores apoyan la integración de VV en Pediatría, siempre como alternativa voluntaria y complementaria a la atención presencial. Los programas futuros deben tener en cuenta las preferencias, sugerencias y barreras reales percibidas por los usuarios.

Virtual visits (VVs) are a type of telemedicine service that entails bidirectional, remote contact between a health care provider and a patient by means of electronic devices.1–4 Back in 1998, the World Health Organization defined telemedicine as the delivery of health care services by health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.5 At present, the Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy) defines it more briefly as the application of telematics to medicine.

Multiple studies have been conducted in different countries to assess the efficacy of telemedicine for follow-up of various pediatric diseases. Most strategies aim at promoting self-management and treatment monitoring. Their results suggest that these tools could promote greater adherence to treatment, reduce unplanned emergency department visits and reinforce the active role of patients and caregivers.6–8 In the field of pediatrics, it has been used successfully, especially in the management of children with chronic diseases such as asthma or diabetes.9

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many health care systems adopted VVs as a temporary solution. Although VVs existed before, it was during this period that their potential to become a viable and efficient alternative to traditional in-person visits became evident, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses.1,10–17

Some of the main advantages of telemedicine include its convenience for patients, since there is no need to travel to health care facilities, saving transport-related time and costs. In the case of pediatric care, it reduces missed school and work hours and lowers the carbon footprint of care.1,16–18 Similarly, they are beneficial in situations in which there is a shortage of health care staff, such as in rural areas. In addition, they can facilitate access to specialists and reduce wait times.2,15,18–21 Finally, we ought to highlight that, during the pandemic, telemedicine helped limit the spread of infection, demonstrating that this type of telemedicine service also reduces disease transmission, as it limits exposure to nosocomial infections, especially in vulnerable patients.1,12,14,15 On the other hand, some of the drawbacks of these services include potentially missing relevant medical information, given the lack of a physical examination, and technological difficulties, such as connection problems or lack of familiarity with digital tools.2,3,15,18

During the pandemic, VVs were an absolute necessity in many cases to ensure continuity of care. Still, the experience during this period made their advantages clear. Today, we know that this care delivery model can improve access, convenience and efficiency, but it also poses challenges in terms of care quality, confidentiality and acceptability for patients and their families. Therefore, before launching a new VV program, it is essential to gain an in-depth understanding of the perceptions of users: patients, parents and caregivers. In this context, a preliminary SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis could help identify both the factors that may favor and the factors that may hinder its implementation.

The aim of our study was to explore the opinions of caregivers and patients regarding the usefulness of VVs in pediatric care.

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study through an anonymous online survey of parents/legal guardians and adolescents to learn about their experiences and perceptions of VVs in pediatric care.

The questionnaire was disseminated by means of a QR code and the survey conducted through the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform, with access to the questionnaire allowed for a period of nine months. The survey was advertised by hanging printed posters and handing out leaflets with information about the project that contained the QR required to access the online form. When participants accessed the survey, they were informed of the objective of the study and asked to provide consent to the use of the data for the purposes of research and publication. The anonymous questionnaire loaded once consent had been provided. The questionnaire was used to collect information about general sociodemographic characteristics, the use of health care services and specific aspects related to VVs. The different versions of the questionnaire—a specific form for parents/legal guardians and an adapted version for patients aged less than 18 years—can be found in the supplemental material (Appendix B).

In addition to assessing how VVs were perceived overall, we analyzed whether responses varied according to certain demographic characteristics, such as sex, age, socioeconomic status or access to the health care center. The data were collected and handled using the REDCap electronic data capture tool hosted by SEPAR (Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica).22,23 REDCap is a secure web-based application designed to support data collection for medical research, providing an interface for data capture and export to statistical software packages. The statistical analysis was conducted with Stata version 16.0. In the descriptive analysis, the data were summarized as means and percentages, and in the comparative analysis, we used the χ2 test for qualitative variables and linear regression to analyze associations and explore factors associated with the perceived usefulness of VVs.

The study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and current law on the protection of personal data. We obtained approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Navarre and the administration of the Hospital Universitario de Navarra (ethics code: PI 2023/55/Protocol version 3.1 of June 8, 2023).

ResultsA total of 426 participants (319 caregivers and 110 patients) submitted complete responses. Tables 1 and 2 present the characteristics of the sample.

Description and sociodemographic characteristics of the caregivers (n = 316) included in the study.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Relationship to minor | |

| Father | 39 (14.72) |

| Mother | 212 (80) |

| Legal guardian | 3 (1.13) |

| Grandparent | 6 (2.31) |

| Educational attainment | |

| Compulsory secondary education (ESO) | 18 (6.92) |

| Non-compulsory secondary education (bachillerato) | 14 (5.38) |

| Undergraduate degree | 84 (32.31) |

| Graduate degree (master, doctorate) | 110 (42.31) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed outside the home | 119 (37.66) |

| Self-employed | 26 (8.23) |

| Employee or civil servant | 117 (37.03) |

| Not employed: | 32 (10.13) |

| Retired | 6 (20) |

| Unemployed | 5 (16.67) |

| Homemaker | 19 (63.33) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 228 (89.06) |

| Divorced/separated | 13 (5.08) |

| Widowed | 2 (0.78) |

| Place of residence | |

| Navarre | 173 (69.76) |

| Outside Navarre | 73 (29.44) |

| Distance between residence and hospital | |

| City, near hospital | 162 (62.79) |

| City, far from hospital (>30 min by car) | 3 (1.16) |

| Town, near hospital | 83 (32.17) |

| Town, far from hospital (>30 min by car) | 10 (3.88) |

| The main reason you visit the hospital is… | |

| Emergency care | 58 (22.57) |

| Outpatient care | 61 (23.74) |

| Emergency and outpatient care | 77 (29.96) |

| Follow-up in outpatient care clinics | |

| Pediatric pulmonology | 64 (18.25) |

| Pediatric cardiology | 12 (3.8) |

| Pediatric endocrinology | 19 (6.01) |

| Pediatric nephrology | 7 (2.22) |

| Pediatric gastroenterology | 21 (6.65) |

| Pediatric neurology | 23 (7.28) |

| Other specialty | 65 (20.57) |

| No outpatient follow-up at hospital | 112 (35.44) |

| Frequency of hospital visits | |

| Once a year or less | 48 (18.68) |

| Twice a year | 99 (38.52) |

| Three times a year | 29 (11.28) |

| 4−6 times a year | 19 (7.39) |

| Once a month | 23 (8.95) |

| One or more times a month | 5 (1.95) |

| Do you have… | |

| A car | 237 (92.58) |

| A mobile phone, tablet or computer with a camera | 251 (98.43) |

| Internet access at home | 250 (98.04) |

| Difficulty traveling to the hospital | 29 (11.28) |

Description and sociodemographic characteristics of patients (n = 110) included in the study.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Place of residence | |

| Navarre | 75 (75.76) |

| Distance between residence and hospital | |

| City, near hospital | 75 (70.09) |

| City, far from hospital (>30 min by car) | 5 (4.67) |

| Town, near hospital | 21 (19.63) |

| Town, far from hospital (>30 min by car) | 6 (5.61) |

| Reason for visiting hospital | |

| Emergency care | 30 (28.04) |

| Outpatient care | 20 (18.69) |

| Emergency and outpatient care | 50 (46.73) |

| Never visited the hospital | 7 (6.54) |

| Follow-up in outpatient care clinics | |

| Pediatric pulmonology | 21 (17.5) |

| Pediatric cardiology | 3 (2.50) |

| Pediatric endocrinology | 12 (10) |

| Pediatric gastroenterology | 4 (3.33) |

| Pediatric neurology | 3 (2.50) |

| Did not know | 20 (16.67) |

| Other specialties | 13 (10.83) |

| No follow-up at hospital | 11 (9.17) |

| Frequency of hospital visits | |

| Never | 11 (10.28) |

| Once a year or less | 31 (28.97) |

| Twice a year | 31 (28.97) |

| Three times a year | 22 (20.56) |

| 4−6 times a year | 5 (4.67) |

| Once a month | 5 (4.67) |

| One or more times a month | 2 (1.87) |

| Travel to hospital | |

| Can walk to hospital | 51 (42.50) |

| Can take public transport | 57 (47.50) |

| Can go in family car | 66 (55) |

| Getting to the hospital is complicated | 8 (6.67) |

The mean (SD) age of the 316 caregivers was 43.3 (7.94) years, with a range of 20 to 77 years, and they had a mean of 2.1 children (minimum, 1; maximum, 8). The sole inclusion criterion for inclusion of caregivers in the survey was having at least one child under the age of 18 in their care. Most participating caregivers were mothers (80%) and were married (89%). With regard to educational attainment, 75% had an undergraduate degree or higher. In addition, 37.7% worked outside the home and 10% were not working at the time of the survey. Nearly 70% resided in Pamplona, and most lived in cities close to their health care center, although 23% lived in towns far from the hospital (defining “far” as more than 30 min by car). Most owned a car (93%), had internet access at home (98%) and owned electronic devices with cameras (98%). However, 10% of caregivers reported having difficulty traveling to the hospital. Table 1 provides a more detailed description of the caregivers (parents or legal guardians).

The patient sample included 110 participants, with a mean (SD) age of 15.5 (3.3) years (range, 8–19 years). Three-quarters lived in a city and near the hospital, 20% in a nearby town and only 6% more than 30 min away by car. The most frequently used pediatric specialty services corresponded to pediatric pulmonology (17.5%), and 16.7% of patients did not know which specialty they were receiving care from. Slightly more than one-quarter of patients visited the hospital once a year, and approximately 25% visited it about twice a year. In terms of transportation, only 6.7% reported difficulty traveling to the center. Table 2 presents the rest of the sociodemographic characteristics of the pediatric patients.

With respect to the caregivers’ previous experience with VVs or telemedicine in general, almost one-third reported never having had a telephone consultation, virtual visit or videoconference with a health care professional (30%); however, half (57%) reported having received telephone calls from their pediatrician and 25% from their nurse at the primary care center. Adolescents, however, reported no previous experience with telemedicine (only 1.1% reported having received or participated in a phone call with a health care professional).

Caregivers’ opinions on the usefulness of virtual visits in pediatric careNearly two-thirds of caregivers (64.12%) thought that VVs could be useful in pediatric primary care, and approximately half (47.18%) that they could also be useful in hospital-based care. With regard to their specific usefulness in hospital-based care, the results indicate that caregivers thought VVs would be particularly valuable for follow-up specialty care visits (58.14%). In addition, half of these participants believed that VVs could be useful for follow-up after hospitalization or after an emergency department visit (70.50% and 79.17%, respectively). With regard to the different specialties, a higher proportion of respondents considered that VVs would be useful in gastroenterology (40.20%), followed by pulmonology (37.54%) and endocrinology (32.6%). However, 13.62% believed that VVs were not useful in any type of pediatric care.

Concerning the most appropriate context for the use of VVs, the most widely accepted option was reporting test results (66.78%), followed by follow-up visits (52.82%) and for assessing the effect of a new treatment (46.84%). Ninety-one percent did not consider VVs appropriate for a first visit with a specialist. With regard to patient age, participants considered VVs more useful for older children: only 24% thought they were appropriate for infants, while more than 70% believed they were a useful alternative for adolescents.

Lastly, with respect to the optimal duration of visits, almost two-thirds considered that they should last between 5 and 15 min, while less than 5% recommended durations longer than 30 min and only 4.57% preferred visits of less than 5 min. Two-thirds of surveyed caregivers believed that, in certain situations, a virtual visit could be a good alternative to a conventional in-person consultation.

As for weaknesses or concerns regarding the implementation of VVs, the most prevalent was the fear of missing appointments due to nor picking up the call (35.55%). This was followed by problems due to a poor internet connection (19.93%) and the risk of health care data leaks (10.63%). Only 5.98% expressed concerns related to not knowing how to use a computer properly, and a quarter of the sample stated having no concerns in this regard. When it came to strengths and positive aspects, the main benefit perceived by caregivers was saving time (53.16%), followed by the child missing fewer hours of school (40.20%) and saving travel expenses (39%).

When asked specifically how they would rate their hospital offering VVs for follow-up in pediatric specialty care (on a scale of 0 to 10), the average rating was 8.06, reflecting a high level of interest. Lastly, 87% of caregivers expressed that if their hospital offered VVs, they would consider it a very good option.

Adolescents’ perception of virtual visitsHalf of the 110 surveyed adolescents thought that VVs could be useful in primary care (54.17%), while approximately 40% thought that they would also be useful for hospital-based care. Only 20% believed that VVs were not useful in pediatric care.

With respect to the optimal duration of VVs, half of the adolescents considered that they should last between 5 and 15 min, and 30% that the ideal duration would be less than 5 min.

The main weaknesses or concerns expressed by adolescents were the possibility of not being able to answer the call (31.67%) and having an unstable internet connection (30.83%). Twenty-five percent expressed concern that their parents or guardians would not know how to use the computer and 21% that their parents would be present.

One of the concerns mentioned most frequently by adolescents was the lack of privacy during consultations, especially when parents are present. Some said they would prefer to have time alone with the doctor. Finally, they expressed concerns about security and confidentiality (9%), such as the possibility of “screenshots being taken without permission.” Regarding the strengths and positive aspects of VVs, the advantage mentioned most frequently was saving time on travel (64%) and the reduction in pollution (48%), followed by their parents missing less work and them missing fewer classes at school (39.17% and 28.33%, respectively). Last of all, 88.57% of adolescents expressed that if their hospital offered VVs, they would consider it a good option.

We studied the factors associated with a greater perceived usefulness of VVs in pediatric care. With regard to the person responding to the survey, we observed that 78% of fathers, 84% of mothers, 100% of legal guardians and 50% of grandparents considered VVs useful (P = .459). When it came to educational attainment, we found a significant association (P = .007), with 76% of participants with a high school education, 84% of those with an undergraduate degree and 92.5% of participants with graduate degrees rating VVs as useful, suggesting that acceptability increases with educational attainment.

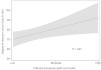

On the other hand, when we analyzed difficulties in accessing the center using a linear regression model, we found a significant association between the difficulty accessing the facility and the level of interest in VVs (P = .021). Fig. 1 illustrates this association, showing that as access difficulty increases, so does the interest in VVs. In the graph, the horizontal axis represents how difficult it is to reach the health care facility, categorized as low, medium or high, while the vertical axis represents the degree of interest in VVs on a scale of 0 to 100. The line shows the general trend, and the shaded area corresponds to the confidence interval.

We found no significant differences in the perceived usefulness of VVs based on marital status, employment status, ownership of a private vehicle or access to devices with cameras and internet access at home, possibly due to the widespread availability of these resources in our sample. Nevertheless, we observed some interesting trends. For example, 87% of participants without a car considered VVs useful compared to 73% of those who owned a vehicle, which suggests that lacking a means of transport could make VVs more appealing, although this difference was not statistically significant (P = .704). Similarly, participants who did not have devices with cameras or internet access at home tended to rate VVs less positively (75% considered them useful) compared to those who did have access to these resources (83.9%). However, this difference was also not significant (P = .633).

Finally, 90% of those who visited the hospital more than once a month rated VVs as useful compared to 63% of those who had not visited the hospital in the past year; that is, the more frequently families have to visit the hospital, the higher they tend to rate VVs (P = .0338).

We performed a comparative analysis of the opinions and suggestions expressed by caregivers and adolescents (Table 3). There were few significant differences in the opinions of the two groups. A greater percentage of caregivers reported previous experiences with telemedicine (70% vs 1.1%; P < .001). In both groups, a high proportion of participants considered VVs useful for receiving test results or for follow-up visits, but some adolescents also considered them appropriate for first visits, while caregivers rarely did (33.3% vs 8.3%; P = 0.031). Finally, adolescents preferred shorter VVs and highlighted the reduced environmental impact and carbon footprint of these visits as an advantage, while they attached less importance to missing fewer classes or school hours (Table 3).

Comparative analysis of the experience with virtual visits (VVs) and their perceived usefulness in pediatric care in caregivers vs adolescents. Analysis of experiences and perceived weaknesses and strengths of VVs, expressed as percentages.

| Caregivers n = 316 | Adolescents n = 110 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous telemedicine experiences (%) | 70.0 | 1.1 | <.001 |

| Usefulness of VVs (%) | |||

| Useful for primary care | 64.12 | 54.17 | .171 |

| Useful for hospital-based care | 47.18 | 40.0 | .434 |

| Not useful in any case | 13.62 | 20.0 | .141 |

| Context in which VVs are useful | |||

| For reporting of test results | 66.78 | 66.67 | .989 |

| For follow-up visits | 52.82 | 75.0 | .091 |

| For initial visit | 8.31 | 33.33 | .021 |

| Ideal duration of VVs (%) | |||

| < 5 min | 4.17 | 30.33 | .011 |

| 5−15 min | 66.66 | 50.0 | .053 |

| Main perceived weaknesses (%) | |||

| Fear of missing appointment | 35.55 | 31.67 | .176 |

| Fear of poor connection/technical problems | 19.93 | 30.83 | .047 |

| Concern about parental presence | ---- | 21.0 | |

| Concerns about security/confidentiality | 10.63 | 9.0 | .061 |

| Main perceived advantages (%) | |||

| Saving time | 53.16 | 64.0 | .068 |

| Reduced pollution/carbon footprint | 8.31 | 48.67 | .019 |

| Reduction in missed classes/school | 40.2 | 28.57 | .031 |

| Do you want your hospital to offer VVs? (% yes) | 87.1 | 88.57 | .911 |

Overall, virtual visits were acceptable for both parents/legal guardians and the patients themselves (children/adolescents). Both groups considered that they could be very useful, and it is worth noting that more than 85% of parents and almost 90% of adolescents would be interested in their hospital offering this type of visit. However, both groups mentioned the possibility of all visits becoming virtual visits as one of their main concerns. Both groups recognized the advantages of this type of care, not to completely replace in-person visits, but rather as a complementary modality.

Among the salient results, we observed that younger parents with higher educational attainment expressed greater interest in VVs. This could reflect a greater familiarity and confidence in the use of technological tools among people with higher educational attainment. However, we did not find statistically significant differences in other factors, such as employment status, marital status or ownership of electronic devices and internet access at home, which may be due to the homogeneity of the sample in relation to these aspects. In addition, we found that the greater the distance between the family’s residence and the hospital or the difficulty in accessing the center, the greater the expressed interest in VVs, which suggests that these visits may be especially useful for families facing sociogeographical barriers in accessing in-person care or located in rural areas where access may be more difficult.

With regard to the usefulness of VVs, the surveyed sample stated that they could be useful for receiving the results of diagnostic tests and for follow-up visits. We should mention that neither caregivers nor patients considered them appropriate for a first visit with a specialist. When it came to the main perceived weaknesses, we had expected that the loss of confidential or personal health care data or issues related to security and confidentiality would be among the main weaknesses; however, what concerned both caregivers and adolescents most was the possibility of “missing the appointment” if they did not answer the call. The most frequently perceived advantage/strength was the time saved by VVs. Of note, caregivers tended to attach more importance to saving time and money, while adolescents attached considerable importance to reducing pollution. Another finding worth noting is that caregivers were more concerned about missed school than the patients themselves.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the perceptions, experiences and suggestions of caregivers and patients regarding VVs in pediatrics. However, it has several limitations. The sample consisted mainly of families with high socioeconomic status and high educational attainment that had internet access and owned a private vehicle, which could favor a more positive view of VVs and limit the generalization of the results to other contexts. In addition, the survey participants were mainly recruited from a hospital clinic, although the survey was also advertised through informational posters placed in common areas in the hospital, such as the pediatric emergency room, and some primary care centers. Even so, the sample could be biased, so future phases of the project should have more diverse, broad and representative samples. Lastly, providing access to the survey via QR code may have excluded people without mobile devices or with low digital literacy, but the fact that a majority of adults currently residing in Spain have a mobile phone with internet access reduces this source of bias. In the future, research should be expanded to achieve more diverse samples that are more representative of the population, in addition to conducting studies that also assess the perceptions of health care professionals in order to know their opinions and suggestions before implementing this type of visits.

ConclusionsThis study constitutes a first attempt to understand the opinions of parents, legal guardians and adolescents about VVs in pediatric care. Participants indicated that VVs should be offered as a voluntary option, complementary to in-person visits, and have an average duration of 10 to 15 minutes. Certain strategies should be considered to promote their implementation:

- •

Education and training. Providers should clearly explain how VVs work, ensuring that users understand the process. It is essential to offer a clear alternative if the call cannot be answered. One possible approach to address the concern of missing appointments would be to use a platform in which patients themselves initiate the video call.

- •

Technical support. While telephone calls are the most widely accepted format, if videoconference is chosen, simple technical support should be provided and integrated into the electronic health records system.

- •

Personalization. Adapting the visit format according to patient preferences, offering virtual visits—always as a voluntary option—during in-person visits

- •

Feedback. Establishing channels to collect user opinions and suggestions can help improve the service and tailor it to their needs.

The design of new virtual care programs must focus on these considerations to ensure an experience that is both efficient and satisfying. Proactively addressing the fears and concerns of users can improve acceptability.

Our study is a first step toward implementing VVs in pediatric care, as we found that they were positively perceived by patients and caregivers. We ought to underscore that the aim of our study was solely to evaluate the subjective acceptability of these services, and not their actual clinical utility. Once the program is active, its performance will have to be evaluated objectively in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, accessibility, equity and quality of care to determine its true usefulness in clinical practice. Finally, it will be essential to continue adapting VVs to the changing needs of patients and their families, always taking their opinions and suggestions into account, in order to offer high-quality patient-centered care.

Declaration of the use of artificial intelligence in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work, the authors used artificial intelligence in order to improve the writing and readability and to translate text. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.