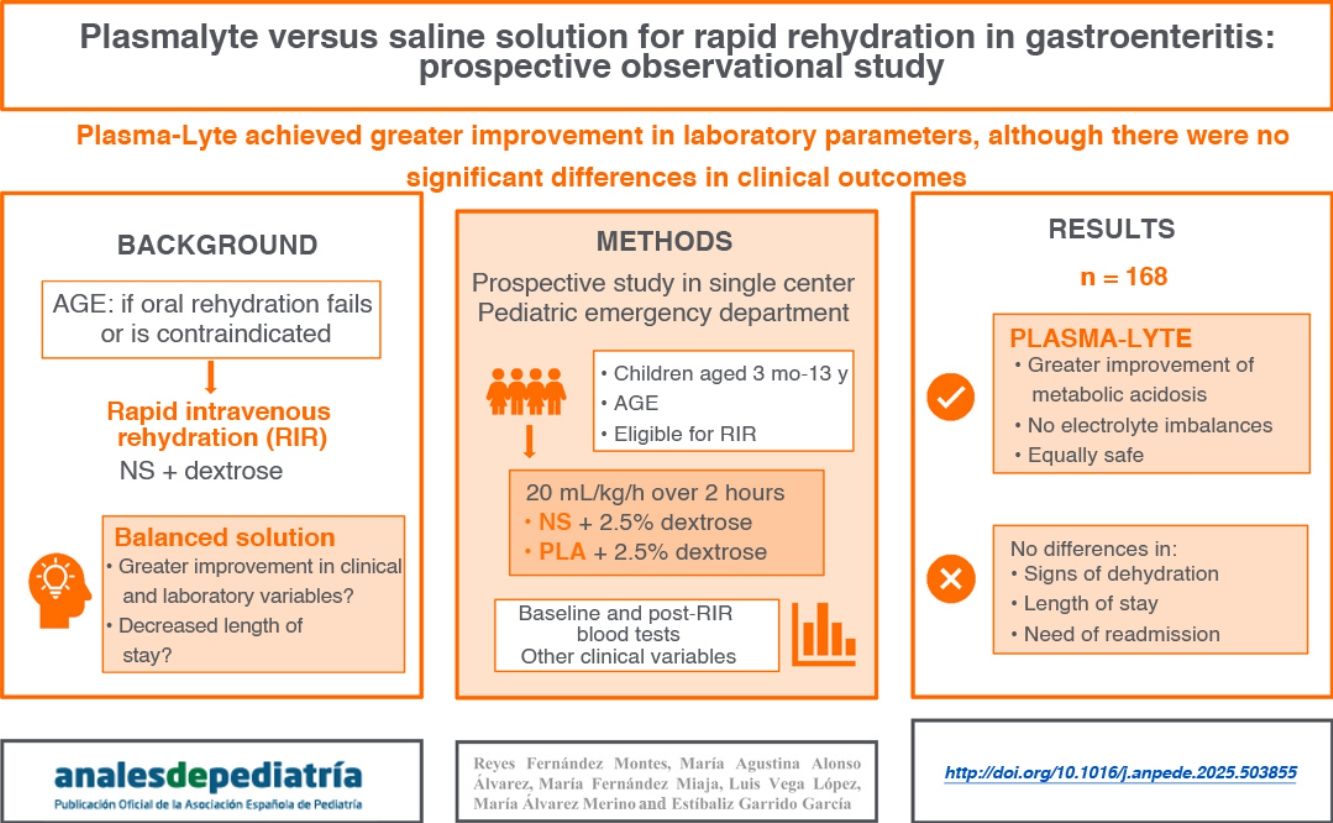

General recommendations suggest using physiological saline solution (PSS) in the guidelines for rapid intravenous rehydration (RIR) in children with dehydration secondary to acute gastroenteritis, although the use of a balanced crystalloid solution, such as Plasmalyte (PLA), could be more beneficial since its composition is more similar to plasma.

Materials and methodsSingle-center prospective and observational study with two treatment groups. The sample consisted of patients aged 3 months to 13 years with mild to moderate dehydration in whom RIR was indicated based on the SEUP guideline, who visited the pediatric emergency department (PED) of a tertiary care hospital. A total of 40mL/kg of solution (PLA or PSS, at the discretion of the physician in charge) supplemented with 2.5% glucose was administered over 2h. We collected data on clinical and laboratory variables before and after RIR, length of stay, need for readmission and adverse events.

ResultsA total of 169 patients (50.9% male; median age, 40 months) completed the study. Of these, 49.1% received PLA. The group that received PLA showed greater improvement in bicarbonate levels (3.7mmol/L vs 1.4mmol/L; P < .001) and a lower increase in chloride levels (0.9mmol/L vs 4.1mmol/L; P < .001). There were no differences in clinical dehydration scales, length of stay in PED or need for readmission. No serious adverse events were observed.

ConclusionsThe use of PLA in the RIR protocol was effective and safe, showing greater recovery of bicarbonate with lesser elevation of chloride levels compared to the use of PSS. However, we did not find differences in clinical outcomes.

Las recomendaciones generales sugieren utilizar suero salino fisiológico (SS0,9%) en las pautas de rehidratación intravenosa rápida (RIR) en niños con deshidratación secundaria a gastroenteritis aguda, si bien el uso de una solución balanceada, como Plasmalyte (PLA), dada su composición más similar al plasma, podría ser más beneficioso.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, prospectivo, unicéntrico, con dos grupos de tratamiento. Se incluyeron pacientes entre 3 meses y 13 años con deshidratación leve-moderada, con indicación de RIR según documento recomendaciones de SEUP, que consultaron en la Sección de Urgencias Pediátricas (SUP) de un hospital de tercer nivel. Se administraron 40ml/kg de suero (PLA o SS0,9%, a criterio del médico responsable) suplementado con glucosa 2,5% en 2 horas. Se recogieron datos clínicos y analíticos pre y post-RIR, tiempo de estancia, necesidad de reingreso y eventos adversos.

Resultados169 pacientes (50,9% varones, mediana edad 40 meses) concluyeron el estudio. El 49,1 % recibió PLA. El grupo que recibió PLA presentó una mayor mejoría en los niveles de bicarbonato (3,7mmol/L frente 1,4mmol/L, p<0,001) y menor aumento de la cloremia (0,9mmol/L frente 4,1mmol/L, p<0,001). No se encontraron diferencias en escalas clínicas de deshidratación, tiempo de estancia en SUP o necesidad de reingreso. No se observaron eventos adversos graves.

ConclusionesEl uso de PLA en pauta de RIR fue efectivo y seguro, comprobándose una mayor recuperación del bicarbonato con menor elevación de la cloremia respecto al uso de SS0,9%. Sin embargo, no hemos encontrado diferencias en cuanto a resultados clínicos.

Acute gastroenteritis (AGE) is a frequent condition in the pediatric age group that causes significant morbidity and consumption of health care resources.1 Most cases require minimal medical intervention, although patients with prolonged vomiting or diarrhea may develop dehydration or hypoglycemia as the main complications.2 Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is the first-line treatment for dehydration, but in cases of severe rehydration or in which ORT fails or is contraindicated, intravenous rehydration (IVR) is the alternative treatment of choice.3

Compared to classic IVR, which is administered over a minimum of 24h, in recent decades the use of rapid intravenous rehydration (RIR) protocols has become widespread,4 consisting in the rapid infusion of a generous volume of isotonic solution with the aim of restoring tissue perfusion, facilitating early correction of acid-base and electrolyte imbalances as well as oral tolerance through the improvement of renal and gastrointestinal perfusion.5 This translates to shorter stays in the emergency room, which in turn improves patient comfort, patient flow through emergency care pathways, which are usually saturated, and efficiency.6

Multiple studies have demonstrated the safety of RIR therapy,7 but there is still no consensus regarding the optimal fluid to administer for the purpose.1 Although general guidelines to date have chiefly recommended the use of normal saline (NS, 0.9% sodium chloride),1,8 with or without added dextrose, given its greater availability and lower cost, the use of balanced crystalloid solutions such as Plasma-Lyte 148 (PLA) (Baxter International, Deerfield, USA) or lactated Ringer solution seem to offer a reasonable alternative for IVR in children with AGE,1,9,10 as suggested by a recent Cochrane review.11

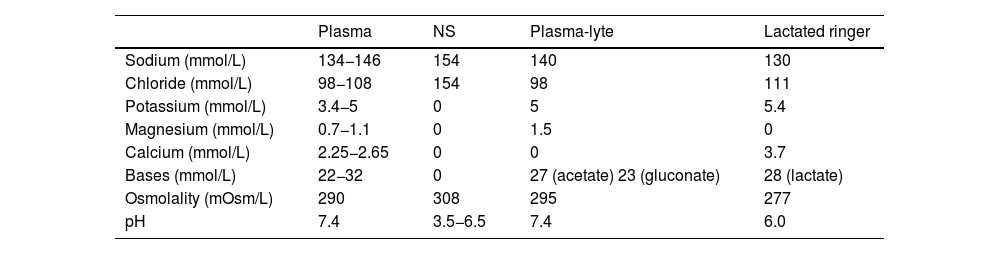

When administering large volumes of NS, its high chloride content can contribute to the development of hyperchloremic acidosis, especially in patients who are likely to develop metabolic acidosis on account of their disease.8,12 Thus, balanced crystalloid solutions, which have ion contents closer to those of extracellular fluid (Table 1), could theoretically decrease the likelihood of adverse effects on acid-base balance.13

Composition of plasma and the main commercial electrolyte solutions.

| Plasma | NS | Plasma-lyte | Lactated ringer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 134−146 | 154 | 140 | 130 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 98−108 | 154 | 98 | 111 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.4−5 | 0 | 5 | 5.4 |

| Magnesium (mmol/L) | 0.7−1.1 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.25−2.65 | 0 | 0 | 3.7 |

| Bases (mmol/L) | 22−32 | 0 | 27 (acetate) 23 (gluconate) | 28 (lactate) |

| Osmolality (mOsm/L) | 290 | 308 | 295 | 277 |

| pH | 7.4 | 3.5−6.5 | 7.4 | 6.0 |

Abbreviation: NS, normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride).

The potential benefits of balanced crystalloid solutions in different settings have been investigated in recent years with contradictory results.14,15 Although several studies found a decrease in mortality and renal dysfunction in critically ill patients (adult as well as pediatric) treated with balanced solutions compared to NS,8,16–18 these benefits were not observed in noncritically ill adult patients managed in the emergency care setting.19

At present, there are several clinical trials underway comparing the use of balanced crystalloid solutions versus NS in critically ill children for both maintenance and bolus fluid therapy.20,21 However, there are few studies in the current literature analyzing the role of these fluids for IVR in children with dehydration secondary to AGE,9,10,22 some of which have found improvement in the recovery of serum bicarbonate levels and lesser increases in serum chloride levels in patients rehydrated with balanced solutions, also describing a consistent clinical improvement in terms of greater improvement in hydration status at 2h of RIR initiation10 associated with a shorter stay in the emergency department.22

The aim of our study was to compare the usefulness and safety of PLA versus NS for RIR, with the hypothesis that PLA would achieve quicker improvement in hydration status and recovery of acid-base balance in addition to being tolerated better.

Material and methodsStudy designProspective observational study conducted in the pediatric emergency department (PED) of a tertiary care hospital in Spain between January 2022 and April 2023. The study was approved by the regional Research Ethics Committee.

ParticipantsPatients aged 3 months to 13 years with mild to moderate dehydration (assessed by means of the Gorelick23 scale or measured weight loss) secondary to AGE in whom ORT was contraindicated3 (losses greater than 10mL/kg/h, dehydration >10%, altered level of consciousness, severe deterioration of general health, paralytic ileus, acute abdomen or severe vomiting) or had failed. We sought informed consent from the legal guardians of the patients and patients aged 12 or more years.

We excluded patients in whom RIR was contraindicated1 (hemodynamic instability, serum sodium <130mmol/L or >150mmol/L, blood glucose >140mg/dL, systemic disease affecting hemodynamic and/or fluid and electrolyte homeostasis).

Patients with blood glucose levels of less than 50mg/dL who met all other inclusion criteria received a bolus of saline with 10% dextrose at a dose of 3mL/kg before administration of RIR and were included in the study if the capillary blood glucose level normalized within 10min, with the reading at this time recorded as the baseline glucose value.

We calculated that we needed a minimum sample size of 80 patients per group for a level of significance of 5%, a power of 80% and detection of a minimum mean difference of 1.5mmol/L in bicarbonate levels.

Study protocolPatients who met the inclusion criteria based on a clinical evaluation and performance of laboratory tests (complete blood count, blood chemistry panel including renal function electrolyte panels, venous blood gas analysis, capillary ketone and glucose levels) received a course of RIR consisting of intravenous infusion over two hours of 40mL/kg (maximum of 1400mL) of one of the two crystalloid solutions compared in the study, selected based on the judgment of the physician in charge of the patient. Both solutions were supplemented with 2.5% dextrose through the addition of 25mL of 50% dextrose stock solution to 475mL of the crystalloid solution with the aim of correcting the increased ketone levels commonly found in these patients.1 The crystalloid solutions were prepared by the nursing staff of the PED per the customary protocol.

Patients remained in the observation unit of the PED during treatment. Once the course of RIR was completed, the patient underwent a second clinical evaluation and laboratory workup, in addition to assessment of oral tolerance with oral rehydration solution per the customary protocol. The physician in charge decided whether to discharge the patient home following a period of observation or admit the patient to the ward. Patients who received RIR at night remained in observation until the next morning to promote rest.

Data collectionWe collected data on demographic, anthropometric and clinical characteristics: age, sex, weight, symptoms, duration of symptoms, vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, score in the Gorelick scale23) at diagnosis and after completion of RIR. The laboratory parameters recorded at baseline were urea, creatinine, C-reactive protein, electrolytes, venous blood gas, capillary ketone and glucose. The parameters recorded upon completion of RIR were venous blood gas and capillary ketone and glucose levels.

We documented the most common complications (venous infusion extravasation, signs of fluid overload) as well as any other unexpected adverse event to assess the safety of the RIR protocol.

All the data were collected prospectively in a form designed for the purpose, kept in the custody of the principal investigators, and eventually entered in a database developed with the SPSS software (IBM, Armonk, USA) following anonymization through the use of the numerical code assigned to each patient at the time of inclusion in the study.

Statistical analysisThe primary outcome was the change in bicarbonate values, expressed in mmol/L, during the patient’s participation in the study (bicarbonate after completion of RIR – baseline bicarbonate).

We analyzed the following secondary outcomes: change in venous chloride, sodium and potassium levels and in capillary glucose and ketone levels between baseline and RIR completion, length of stay in PED, frequency of hospital admission and readmission and incidence of adverse events.

The statistical analysis was performed with the software package SPSS and performed by intention to treat. We expressed normally distributed variables as mean and standard deviation, using the Student t test to compare groups. For data that did not follow a normal distribution, we used the median and interquartile range in the descriptive analysis and compared groups by means of the Mann-Whitney U test. Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies and group comparisons made by means of the χ2 test.

For the assessment of changes in variables between baseline and completion of treatment, we used simple linear regression in the case of quantitative variables and univariate logistic regression models for qualitative variables.

The incidence of adverse events was compared using the χ2 test.

We considered results with a P value of less than 0.05 statistically significant.

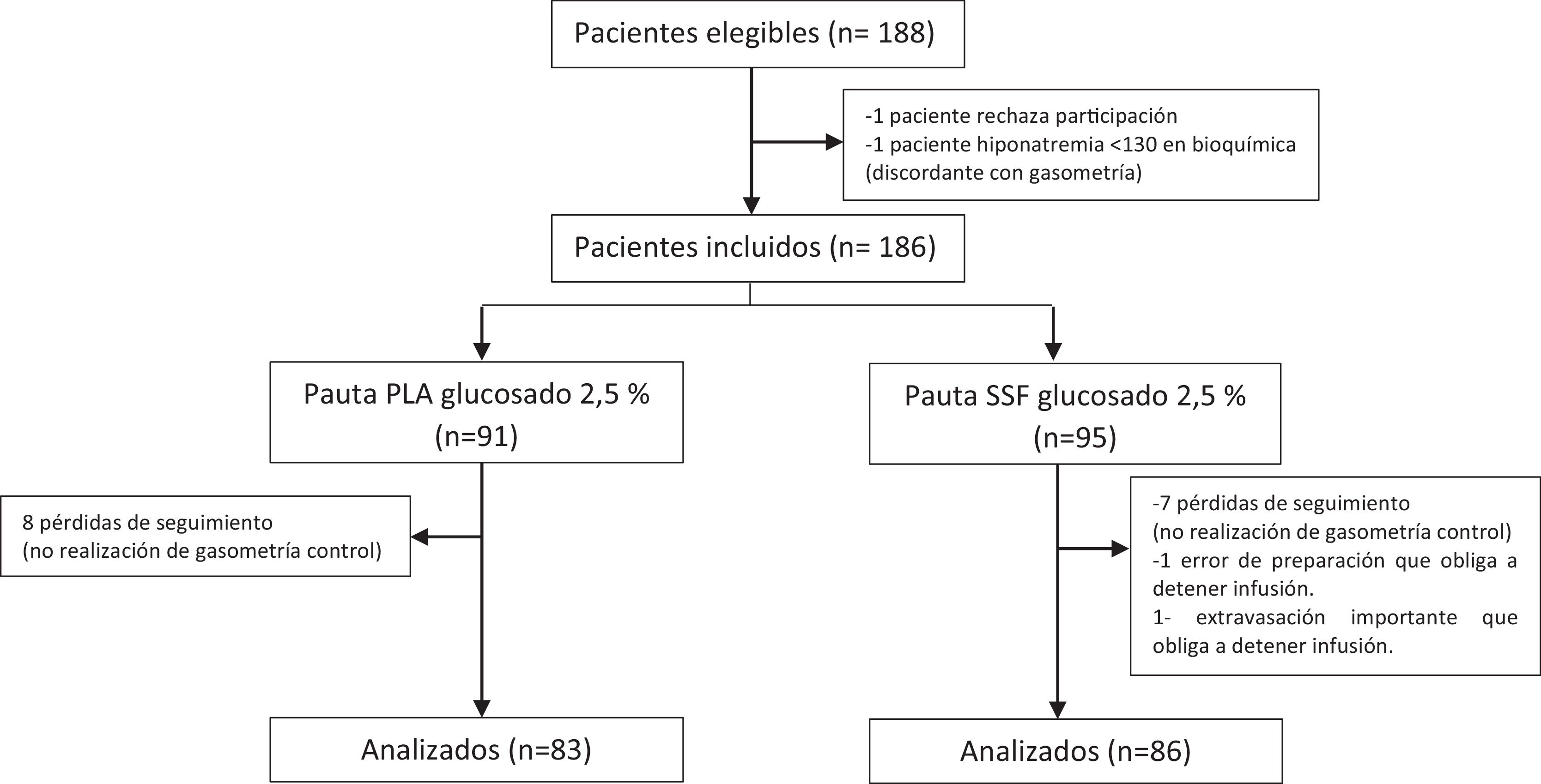

ResultsBaseline characteristics of the sampleA total of 186 patients were included in the study, of who 169 completed it; the patients had ages ranging from 6 to 167 months (median, 40 meses) and 49.1% were female; 86 (50.9%) received normal saline with 0.9% sodium chloride and 2.5% dextrose (D2.5NS) and the remaining 83 (49,1%) Plasma-Lyte with 2.5% dextrose (PLA with dextrose). Fig. 1 presents a flow diagram of the patients’ progress throughout the study.

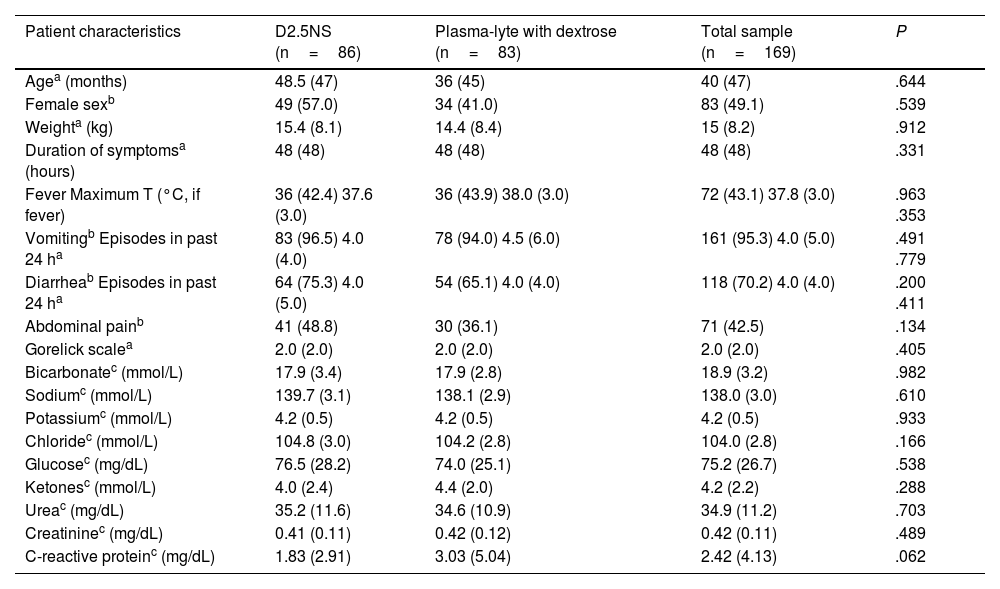

Table 2 compares the demographic, anthropometric, clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients at baseline. We did not find statistically significant differences between groups in any of these variables.

Comparison of baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics of the total sample and the two treatment groups.

| Patient characteristics | D2.5NS (n=86) | Plasma-lyte with dextrose (n=83) | Total sample (n=169) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea (months) | 48.5 (47) | 36 (45) | 40 (47) | .644 |

| Female sexb | 49 (57.0) | 34 (41.0) | 83 (49.1) | .539 |

| Weighta (kg) | 15.4 (8.1) | 14.4 (8.4) | 15 (8.2) | .912 |

| Duration of symptomsa (hours) | 48 (48) | 48 (48) | 48 (48) | .331 |

| Fever Maximum T (°C, if fever) | 36 (42.4) 37.6 (3.0) | 36 (43.9) 38.0 (3.0) | 72 (43.1) 37.8 (3.0) | .963 .353 |

| Vomitingb Episodes in past 24 ha | 83 (96.5) 4.0 (4.0) | 78 (94.0) 4.5 (6.0) | 161 (95.3) 4.0 (5.0) | .491 .779 |

| Diarrheab Episodes in past 24 ha | 64 (75.3) 4.0 (5.0) | 54 (65.1) 4.0 (4.0) | 118 (70.2) 4.0 (4.0) | .200 .411 |

| Abdominal painb | 41 (48.8) | 30 (36.1) | 71 (42.5) | .134 |

| Gorelick scalea | 2.0 (2.0) | 2.0 (2.0) | 2.0 (2.0) | .405 |

| Bicarbonatec (mmol/L) | 17.9 (3.4) | 17.9 (2.8) | 18.9 (3.2) | .982 |

| Sodiumc (mmol/L) | 139.7 (3.1) | 138.1 (2.9) | 138.0 (3.0) | .610 |

| Potassiumc (mmol/L) | 4.2 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.5) | .933 |

| Chloridec (mmol/L) | 104.8 (3.0) | 104.2 (2.8) | 104.0 (2.8) | .166 |

| Glucosec (mg/dL) | 76.5 (28.2) | 74.0 (25.1) | 75.2 (26.7) | .538 |

| Ketonesc (mmol/L) | 4.0 (2.4) | 4.4 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.2) | .288 |

| Ureac (mg/dL) | 35.2 (11.6) | 34.6 (10.9) | 34.9 (11.2) | .703 |

| Creatininec (mg/dL) | 0.41 (0.11) | 0.42 (0.12) | 0.42 (0.11) | .489 |

| C-reactive proteinc (mg/dL) | 1.83 (2.91) | 3.03 (5.04) | 2.42 (4.13) | .062 |

Abbreviations: D2.5NS, normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride) with 2.5% dextrose; T, temperature.

Values expressed as:

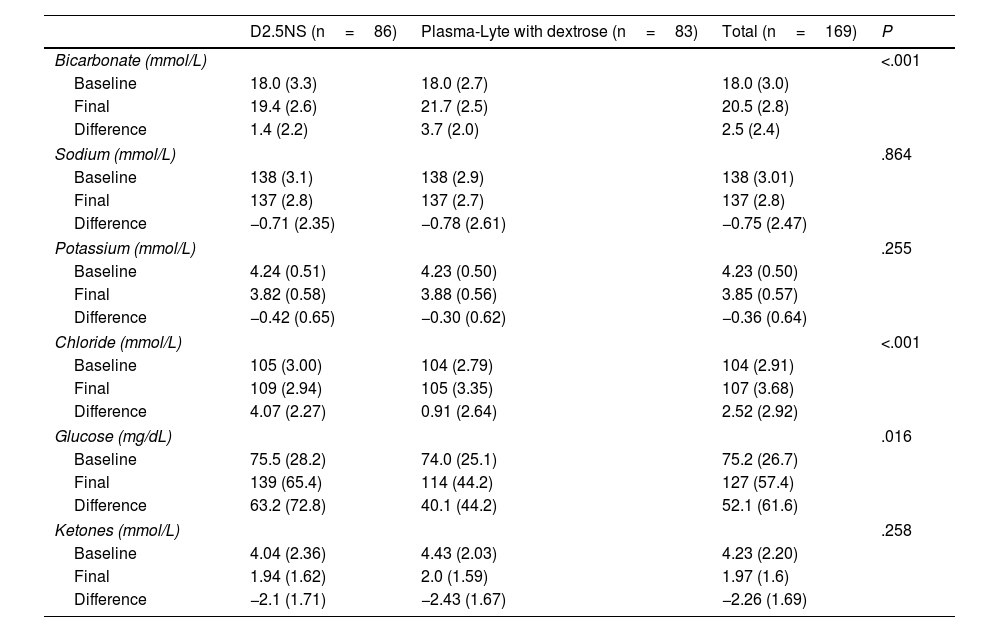

After completion of the course of RIR, patients in the PLA group showed greater recovery of serum bicarbonate levels with a lesser increase in serum chloride levels, compared to the D2.5NS group (Table 3). There were no significant differences between groups in the changes in sodium and potassium levels, and none of the patients developed hyperkalemia.

Change in laboratory values from baseline to completion of treatment in the two treatment groups.

| D2.5NS (n=86) | Plasma-Lyte with dextrose (n=83) | Total (n=169) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | <.001 | |||

| Baseline | 18.0 (3.3) | 18.0 (2.7) | 18.0 (3.0) | |

| Final | 19.4 (2.6) | 21.7 (2.5) | 20.5 (2.8) | |

| Difference | 1.4 (2.2) | 3.7 (2.0) | 2.5 (2.4) | |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | .864 | |||

| Baseline | 138 (3.1) | 138 (2.9) | 138 (3.01) | |

| Final | 137 (2.8) | 137 (2.7) | 137 (2.8) | |

| Difference | −0.71 (2.35) | −0.78 (2.61) | −0.75 (2.47) | |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | .255 | |||

| Baseline | 4.24 (0.51) | 4.23 (0.50) | 4.23 (0.50) | |

| Final | 3.82 (0.58) | 3.88 (0.56) | 3.85 (0.57) | |

| Difference | −0.42 (0.65) | −0.30 (0.62) | −0.36 (0.64) | |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | <.001 | |||

| Baseline | 105 (3.00) | 104 (2.79) | 104 (2.91) | |

| Final | 109 (2.94) | 105 (3.35) | 107 (3.68) | |

| Difference | 4.07 (2.27) | 0.91 (2.64) | 2.52 (2.92) | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | .016 | |||

| Baseline | 75.5 (28.2) | 74.0 (25.1) | 75.2 (26.7) | |

| Final | 139 (65.4) | 114 (44.2) | 127 (57.4) | |

| Difference | 63.2 (72.8) | 40.1 (44.2) | 52.1 (61.6) | |

| Ketones (mmol/L) | .258 | |||

| Baseline | 4.04 (2.36) | 4.43 (2.03) | 4.23 (2.20) | |

| Final | 1.94 (1.62) | 2.0 (1.59) | 1.97 (1.6) | |

| Difference | −2.1 (1.71) | −2.43 (1.67) | −2.26 (1.69) | |

Abbreviation: D2.5NS, normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride) with 2.5% dextrose.

Values expressed as mean (standard deviation).

As regards blood glucose, of the 186 participants, 23 (12.4%) had hypoglycemia on arrival to the PED, requiring administration of a dextrose bolus prior to initiation of RIR. The mean ketone concentration in the sample at baseline was 4.2mmol/L, and levels had decreased after completion of IVR. We found an increase in blood glucose levels in the sample overall, with a greater increase in patients in the D2.5NS group (Table 3). However, the proportion of patients with a final glucose level greater than 140mg/dL was similar in both groups (36% of total sample; 30.1% of PLA with dextrose group, 41.8% of D2.5NS group; P=.149), as was the proportion of patients with final glucose levels greater than 200mg/dL (13.6% of total sample; 9.6% PLA with dextrose group; 17.4% of D2.5NS group; P=.144).

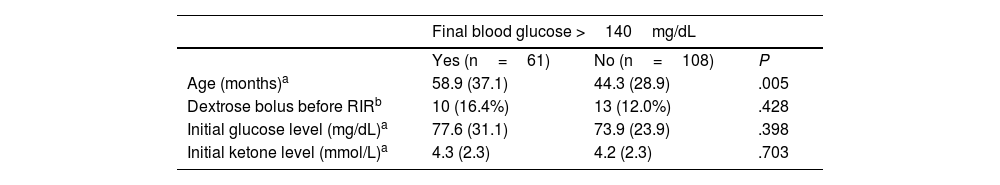

Compared to patient with normal glucose levels, patients who had developed hyperglycemia at the end of the study did not differ significantly in baseline glucose or ketone levels or in the proportion that received a dextrose bolus to correct hypoglycemia prior to initiation of RIR. However, patients with a final glucose level greater than 140mg/dL were significantly older compared to patients with final glucose levels in the normal range (Table 4).

Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients with hyperglycemia at the end of RIR compared to all other patients.

| Final blood glucose >140mg/dL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=61) | No (n=108) | P | |

| Age (months)a | 58.9 (37.1) | 44.3 (28.9) | .005 |

| Dextrose bolus before RIRb | 10 (16.4%) | 13 (12.0%) | .428 |

| Initial glucose level (mg/dL)a | 77.6 (31.1) | 73.9 (23.9) | .398 |

| Initial ketone level (mmol/L)a | 4.3 (2.3) | 4.2 (2.3) | .703 |

| Final blood glucose >200mg/dL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=23) | No (n=146) | P | |

| Age (months)a | 52.4 (36.9) | 49.2 (32.1) | .660 |

| Dextrose bolus before RIRb | 5 (21.7%) | 18 (12.3%) | .221 |

| Initial glucose level (mg/dL)a | 75.3 (34.4) | 75.2 (25.4) | .998 |

| Initial ketone level (mmol/L)a | 4.4 (2.4) | 4.2 (2.2) | .703 |

Abbreviation: RIR, rapid intravenous rehydration.

Values expressed as:

The score in the Gorelick scale after RIR improved by nearly 2 points in the total sample.

Of the 161 patients who presented with vomiting on arrival, 3 received antiemetic treatment with ondansetron.

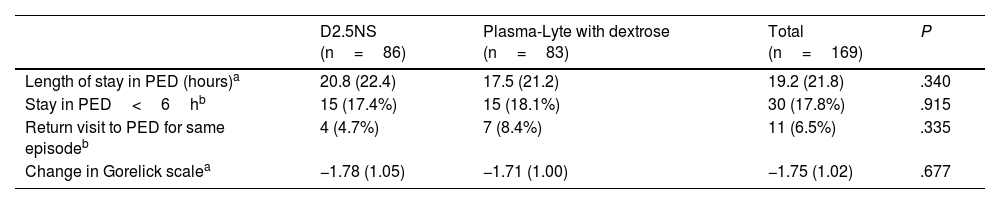

The mean length of stay was 19.2h. Eighteen percent of patients stayed in the PED for less than 6h. Eleven (6.5%) patients returned to the PED for the same reason, one of whom received a new course of RIR. As Table 5 shows, there were no significant differences in these parameters between the treatment groups.

Comparison of Clinical Outcomes in the Two Treatment Groups.

| D2.5NS (n=86) | Plasma-Lyte with dextrose (n=83) | Total (n=169) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay in PED (hours)a | 20.8 (22.4) | 17.5 (21.2) | 19.2 (21.8) | .340 |

| Stay in PED<6hb | 15 (17.4%) | 15 (18.1%) | 30 (17.8%) | .915 |

| Return visit to PED for same episodeb | 4 (4.7%) | 7 (8.4%) | 11 (6.5%) | .335 |

| Change in Gorelick scalea | −1.78 (1.05) | −1.71 (1.00) | −1.75 (1.02) | .677 |

Abbreviations: D2.5NS, normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride) with 2.5% dextrose; PED, pediatric emergency department.

Values expressed as:

The only observed adverse events were extravasation of the venous catheter in 4 of the 169 patients (2.4%), 2 in each treatment group, and development of edema in one patient who received D2.5NS course, with no statistically significant differences between groups.

DiscussionIn a study comparing the management of children with mild to moderate dehydration secondary to AGE with a course of D2.5NS versus a course of PLA with dextrose, we found improved recovery of bicarbonate levels and lower increases in serum chloride levels in the group treated with PLA.

Impact on laboratory parametersWe found improvement in blood gas analysis values in the entire sample, with an increase in serum bicarbonate levels, the laboratory parameter that is most strongly associated with dehydration in patients with AGE,24,25 corroborating the effectiveness of RIR therapy in these patients.

In the group of patients treated with a balanced crystalloid solution, reproducing the findings reported in previous studies,10 the increase in bicarbonate levels was significantly larger. In addition, serum chloride levels, a factor that contributes to the development or persistence of metabolic acidosis,13 were lower in this group, an outcome that can be attributed to the difference in the chloride concentration of the two crystalloid solutions.

Regarding the possible effects of fluid therapy on serum sodium and potassium levels, in agreement with previous studies,10 we found no differences in the changes of either ion levels based on the type of solution used for RIR. A recent Cochrane review11 suggests that the use of balanced solutions may reduce the incidence of hypokalemia after correction of the dehydration secondary to AGE. However, in our study, none of the patients developed hypo- or hyperkalemia during the follow-up. There were also no differences in the changes in potassium levels between the groups, evincing the safety of administering PLA in this respect, given its low potassium content (5mEq/L), the duration of RIR and the range of administered volumes (maximum of 40mL/kg), which corresponds to a maximum delivery of 0.2mEq per kg of body weight.

The entire sample exhibited a reduction in ketone levels of more than 2mmol/L after completion of RIR, consistent with the previous literature,26 with no differences between the groups, which was expected given that both solutions had the same dextrose content. This amount of dextrose supplementation seemed sufficient for the purposes of rehydration, contributing to the correction of high ketone levels, a factor involved in the persistence of vomiting.27 In fact, only 3 of the 161 patients who presented with vomiting on arrival required administration of ondansetron, which was reserved for patients in whom vomiting persisted in spite of bowel rest and IVR.

On the other hand, 36% of the sample had blood glucose levels greater than 140mg/dL upon completion of RIR, with capillary glucose values greater than 200mg/dL in more than 13% of patients, independently of baseline glucose and ketone levels, which brings into question whether the routine addition of 2.5% dextrose suggested in the guideline published by the Working Group on Hydration and Electrolyte Disorders of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas,1 even for patients with normal glucose levels, may not be excessive.

In our sample, patients with final blood glucose levels greater than 140mg/dL were older than patients with normal final blood glucose levels. This suggests that greater caution may be required in regard to dextrose supplementation as patient age increases.

Impact on clinical parametersDespite the marked differences found in the changes of biochemical parameters, the study did not identify significant differences in clinical outcomes in relation to the type of fluid administered to the patients.

We found improvement in the clinical assessment of hydration status by means of the Gorelick scale in the entire sample after administration of RIR, with no significant differences between the two groups. This was not consistent with the greater increase in bicarbonate levels observed in patients in the PLA group, although several publications question the usefulness of clinical scales for assessing the degree of dehydration in children with AEG.28,29

The mean length of stay in the total sample was 19h, slightly less than the 24h required for conventional IVR and shorter compared to the length reported in other studies,9,22 with no differences between the two treatment groups.

Although the main advantage of RIR approaches is a rapid clinical recovery allowing early discharge,6 in our case series only 18% of patients were discharged within 6h. However, it is difficult to interpret these findings given that the decision to discharge a patient home was not based on objective criteria, since the PED lacked a specific protocol for it, but rather left to the judgment of the physician in charge at the time. In addition, all patients that completed RIR at night were kept in observation until the morning after to allow adequate rest, which may have prolonged their stay in the PED beyond what was required based on their clinical condition.

Of the total sample, 6.5% of patients made return visits to the PED for the same complaint, with no differences between the two groups.

Safety of rapid intravenous rehydrationIn agreement with the findings of previous studies,30 we did not identify any severe adverse event during the study beyond intravenous infusion extravasation in 4 of the 169 patients and development of self-limiting edema in one other patient. We did not identify any safety concerns associated with the differences in the composition of each of the solutions.

ConclusionPlasma-Lyte was as effective and safe as NS for delivery of RIR and achieved greater recovery of bicarbonate levels with lower elevation in chloride levels. However, we found no differences in clinical outcomes.

The addition of dextrose to the rehydration solution should be individualized, as the customary 2.5% concentration may be excessive in a large proportion of patients.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the entire staff of the pediatric emergency department and to all the pediatricians and residents who contributed to patient recruitment for their support and cooperation, as well as to the staff of the Biostatistics and Epidemiology Platform of the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria (Health Research Institute) of the Principality of Asturias for their invaluable help in the analysis of the data.

The main results were presented at the 28th Meeting of the Spanish Society of Pediatric Emergencies, held in May 2024 in La Coruña.