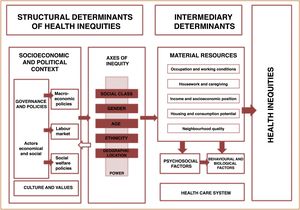

Several studies conducted in the second half of the 20th century evinced that national health systems were unsuccessful in fighting inequalities after the first few decades following their institution.1 These findings and the promotion of the World Health Organization (WHO) of research on the impact of socioeconomic and environmental variables on health have given rise to the current model of health inequities and the social determinants of health (Figs. 1 and 2).2

Conceptual framework of social determinants of inequities in health.

Social determinants of health (SDHs) are the circumstances in which individuals are born, raised, live, work and age, and the systems established to fight disease. Health inequities are unjust and avoidable differences in health care resulting from differences in the social, economic, demographic or geographical context of individuals. They affect opportunities and resources related to health, such as education, housing, occupation and working conditions, and thus contribute to the risk of disease and premature death. Last of all, social exclusion is the phenomenon by which certain individuals or groups are not integrated in society, either due to income limitations or to not adhering to the way of life expected by the society of which they are a part of. Poverty and social exclusion tend to occur together, but this is not always the case, as some poor individuals or households are included in society, while others that are not poor are excluded on account of their ethnicity, religion or values, among other factors. Exclusion hinders social cohesion, and thus gives rise to situations that range from conflicts or decreased road safety to the spread of epidemics like the current coronavirus pandemic. Thus, individual health is also related to population health.

There is a sufficient body of evidence proving the negative impact on health of living with negative SDHs and under conditions of inequality and social exclusion. This manifests in the form of premature death (as demonstrated in Spain by the MEDEA project)3 and the morbidity associated with chronic and acute diseases. An example of the latter can be seen in the current pandemic, as the highest cumulative incidences of infection by SARS-CoV-2 have been recorded in the most vulnerable neighbourhoods. While this deleterious impact on health is important at any age, exposure to adverse living conditions during childhood has a significant long-term impact on adult health, as it is during childhood that essential components of health develop (lifestyle habits, social and emotional development, mental health and academic achievement, among others) that will either limit or promote attainment of the full health potential in adulthood. Some examples of the deleterious impact of negative SDHs in childhood are preterm birth and low birth weight, teen pregnancy, malnutrition (be it undernutrition or obesity), developmental and mental health problems, use of tobacco, alcohol and drugs, oral health problems, infectious diseases like pertussis or tuberculosis, etc.4

While health care systems offering high-quality care and universal access are essential to ameliorate the negative impact on health of inequality and social exclusion, their impact tends to be overestimated at the budget level relative to other measures concerned with health promotion, occupational health or the environment and the improvement of other social determinants of health. Furthermore, we must take into account that inequalities may also be reproduced in those very health care systems. This is illustrated by different studies conducted in countries in the European Union, including Spain, which show unequal access to health care at different levels of care Thus, individuals of lower socioeconomic status tend to make more visits to primary care services and fewer visits to dental providers and hospital-based speciality clinics, and are less likely to use some preventive services.5 As Tudor stated in 1971 in his explanation of what he called the inverse care law, “The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served”.

Primary care paediatrics has some of the fundamental characteristics of the health care system that can fulfil the justice principle, in addition to other core principles of health care ethics: accessibility, as it is the point of entry to the health care system, longitudinality, as the patient is followed up from birth through the end of adolescence, and coordination, as interventions by different health care and social work professionals are aligned to benefit the patient. These characteristics allow paediatric specialists to carry out the necessary interventions to sidestep and/or ameliorate the deleterious and unjust effects of social exclusion on child health and to raise awareness in the population, the authorities and governmental institutions on the importance of addressing its root causes. This requires the performance, publication and dissemination of studies on SDHs and an interest from scientific societies on this line of research. On the other hand, we ought to highlight the scarce training on the impact of SDHs within the paediatrics curriculum, as it may be worth to include this subject in the contents of different subjects and rotations in the different educational tracks.

At present, most primary care paediatricians do not have enough time to address subjects as important as the one discussed in this editorial in their own practice. A more adequate practitioner-to-patient ratio (paediatrician, paediatric nurse, case manager or social worker) and the assignment of specific tasks to specific professionals could improve the implementation of health promotion and prevention interventions in both quantity and quality, as illustrated by the intervention implemented by Garach et al.6 in a study published in the current issue of Anales de Pediatría, developing health care programmes focused on social risk factors, and not just on diseases, designing, promoting and participating in interventions to improve community health, etc.

According to Virchow, “medicine is a social science and politics is nothing but medicine writ large”. Primary care systems were established with the aim of guaranteeing individuals access to health care systems, thereby facilitating adherence to the principles of beneficence and justice. As renowned paediatrician Barbara Starfield stated, primary care is an important aspect of policy in the pursuit of efficacy, effectiveness and equity in health care. In this regard, practitioners of primary care, family and community paediatrics have a key role and responsibility in identifying, raising awareness of and addressing health inequities in our society and in the health care system. The recognition of inequities by paediatric providers and the health care system, on one hand, and by society and policy makers, on the other, is key in order to improve the health of today’s children and tomorrow’s adults.

FundingThe author received no funding for this work.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: S. Tornero Patricio, Pediatría de atención primaria ante las desigualdades en salud y exclusión social. An Pediatr (Barc). 2021;94:203–205.