Parental stress may contribute to neurodevelopmental disorders in children, and lack of sleep may be at the root of the issue. The aim of our study was to assess the association between infant sleep and parental stress, as well as the influence of socioeconomic factors or co-sleeping.d

Material and methodsWe conducted a prospective observational study in children aged 2 years. Parents completed three questionnaires: the Parenting Stress Index-4-Short Form (PSI), the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire and a questionnaire that assessed socioeconomic and sleep-related variables.

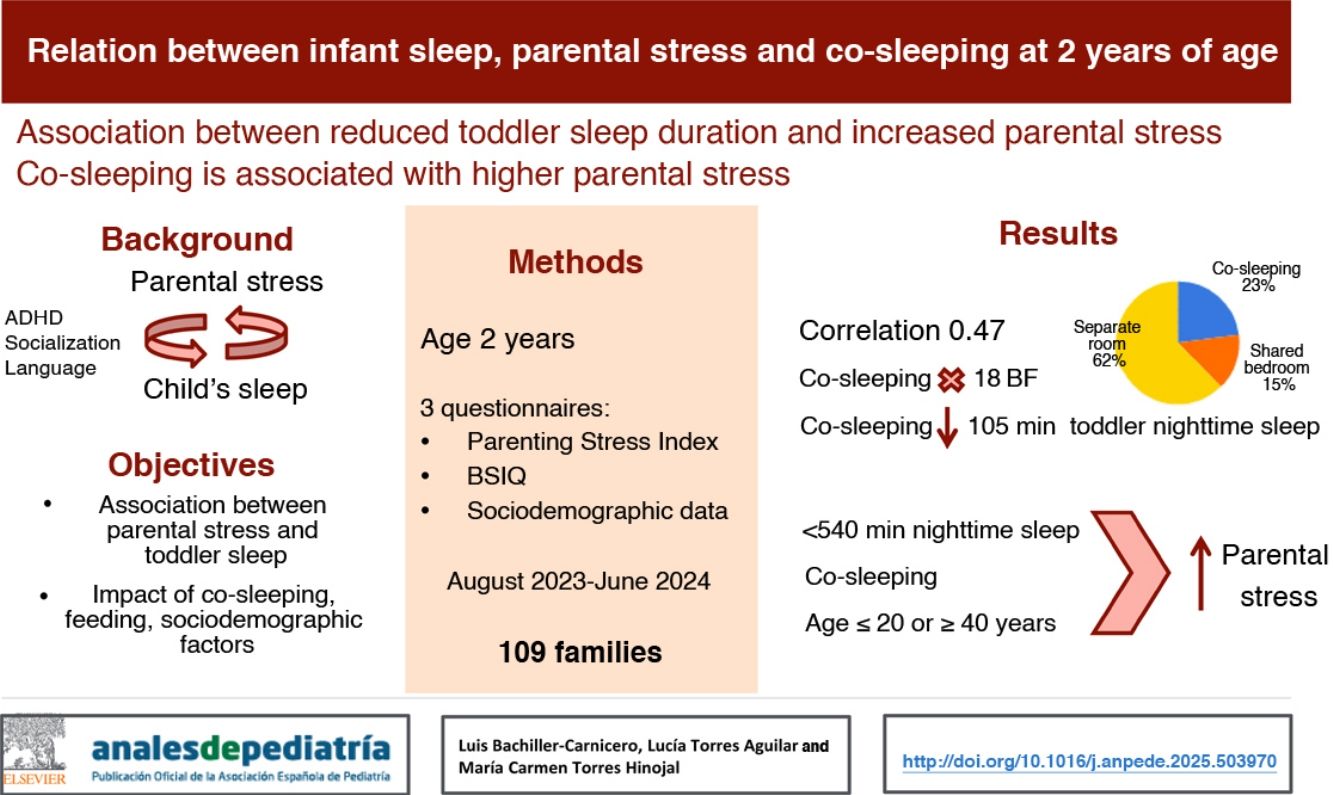

ResultsThe sample included 109 families. The median (interquartile range) duration of nighttime sleep, time spent awake at night and sleep onset latency (in minutes) and number of nocturnal awakenings in the children were 500 (447.5–602.5), 15 (5–60); 1 (0–3) and 10 (8–20), respectively. The mean total score in the PSI was 61.1 (SD, 12.3).

The correlation between the PSI total score and the minutes of nighttime sleep was: 0.478 (P = .001), and we found a significant increase in the PSI total score when nighttime sleep duration in the child was less than 540min, mainly on account of the dysfunctional parent-child interaction and difficult child subscales.

Parental stress was increased significantly with the practice of co-sleeping and with parental age less than 20 years or more than 40 years. Co-sleeping was associated with shorter nighttime sleep duration, more time awake at night and an increased number of nocturnal awakenings.

ConclusionsDecreased infant sleep duration at night caused an increase in parental stress. Likewise, co-sleeping and early or advanced parenthood are associated with a higher level of stress.

El estrés parental puede condicionar alteraciones del neurodesarrollo infantil, pudiendo encontrarse la falta de sueño en el origen. El objetivo del estudio fue comprobar la relación entre el sueño infantil y el estrés parental, así como la influencia de factores socioeconómicos o del colecho.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo observacional en lactantes de 2 años de edad. Los padres completaban 3 cuestionarios: “Parenting stress index-4-Short Form”(PSI), “Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire” y encuesta sobre variables socioeconómica y prácticas de sueño.

ResultadosSe incluyen 109 familias. La mediana y rango intercuartílico de los minutos de sueño infantil nocturno, minutos despierto por la noche, número de despertares y minutos hasta quedarse dormido fueron: 500 (447,5–602,5), 15 (5–60); 1 (0–3) y 10 (8–20). La puntuación media±desviación típica del global del PSI fue: 61,1±12,3.

La correlación entre la puntuación total obtenida en el PSI y los minutos de sueño nocturno, fue de: 0,478 (p=0,001), encontrando un aumento significativo de puntuación total del PSI con menos de 540 minutos de sueño infantil nocturno, principalmente en las subescalas interacción disfuncional padre-hijo/a e hijo/a difícil.

El estrés parental aumentó significativamente con la práctica de colecho y una edad parental ≤ 20 o ≥ 40 años. El colecho asociaba un menor tiempo de sueño nocturno, mayor tiempo despierto por la noche y mayor número de despertares nocturnos.

ConclusionesLa disminución de sueño infantil provoca un aumento del estrés parental. Por otra parte, el colecho y las edades parentales extremas asocian mayor nivel de estrés.

In 1992, Abidin defined parenting stress as the parental perception that the demands placed by their children outstrip their resources.1 This form of stress may stem from feelings of deep sadness or anxiety in parents, dysfunctional parent-child interaction patterns, lack of social support, distorted parental subjective perceptions or difficulties of the child in daily living.2,3 Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children are closely associated with the relationship they develop with their parents, as the parent-child bond combined with adequate parenting skills can promote adequate self-regulation and secure attachment in the child.4

It is estimated that 5%–10% of parents may experience high levels of stress or burnout in their parenting role.5 There is evidence of an association between high parental stress and more rigid and strict parenting styles, decreased parent-child interaction and an increased probability of child maltreatment.6 Parental stress is also associated with an increased risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, language or mood disorders or social/behavioral problems in the child.7,8

On the other hand, sleep disorders are a common and relatively underestimated condition in children and have been found to be associated with cognitive, behavioral, emotional, physical and social interaction difficulties. In the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3), the American Academy of Sleep Medicine defines insomnia as difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or nonrestorative sleep despite adequate circumstances for sleep and causing distress or daytime impairment.9 It is estimated that 30% of children aged 6 months to 5 years experience insomnia.10 The important of sleep at age 2 years is evinced by the impact of nighttime sleep duration on socioemotional development in toddlers or the predisposition to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and delay in language acquisition associated with irregular sleep deprivation.11 It is believed that from age 2 years, there is a transition in the functions of sleep from neural reorganization to neural repair and metabolite clearance.12

Stress and sleep problems are conditions with a bidirectional association, and there is evidence that stress may result in a reduction in sleep duration and quality while insomnia can cause an increase in cortisol levels.13 Sleep arrangements in the household can affect the functioning and stress of the family.14,15

In light of the above, the main objective of our study was to determine the association between toddler sleep quality at age 2 years and parental stress. As secondary objectives, we analyzed the association between parental stress and variables related to sleep habits, such as co-sleeping, as well as demographic factors such as parental age, the presence of siblings and household socioeconomic status.

Material and methodsStudy designWe conducted a prospective observational and analytical study. The sample consisted of families that met the inclusion criteria, including parental signing of informed consent. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the center (reference no. 23-PI175).

SampleThe study was conducted in a primary care center that served a catchment population of 3486 pediatric patients during the study period, of who 194 turned 2 years old during the study.

We included all families who attended the routine health checkup of the child at age 2 years in the framework of the Healthy Child program in our primary care center between August 2023 and July 2024.

The exclusion criteria were: patients with severe underlying disease, such as severe neurologic disorders or moderate to severe cerebral palsy, gastrointestinal disease requiring tube or ostomy feeding or history of congenital disease requiring surgical management in the first 2 years post birth. If the decision to co-sleep was motivated by the previous quantity or quality of sleep in the toddler, the family was excluded from the study because the baseline stress level in these parents could be higher as a result of the child’s insomnia.

Taking as reference the studies conducted by Teti et al. and De Stasio et al, we calculated the sample size required to detect differences in the total score of the Parenting Stress Index, Fourth Edition Short Form (PSI-4-SF) with a power of 90% and a significance level of 0.05. The estimated required minimum sample size was of 105 patients.14,15

InstrumentsDuring the scheduled routine 2-year checkup, parents were given 3 questionnaires:

- none-

PSI-4-SF: short form of the fourth version translated to Spanish. It is a self-report instrument that includes three subscales: parental distress, parent-child dysfunctional interaction and difficult child.1,16 Each subscale is composed of 12 items scored on a scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree), yielding subscale scores that range from 12 to 60 points. The total scale score ranges between 36 and 180 points, and scores above the 85th percentile (≥110 points) are indicative of a high level of stress.

The 3 subscales are:

Parental Distress: assesses the level of distress the parent feels due to personal factors and restrictions related to parenting. High scores are indicative of lower parenting self-efficacy, distress on account of the limitations derived from parenting, conflict in the couple, lack of social support or depression.

Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction: it focuses on the parent’s perception that the child does not meet their expectations. A high score suggests that the parent may consider the child as a negative element in the parent’s life and an inadequate parent-child bond.

Difficult Child: assesses parental perceptions regarding the child’s temperament, noncompliance and demanding behavior. A high score is indicative of parental perception of the child’s behavior as problematic.

This instrument has been widely used in families with chronic medical conditions, and previous studies of its psychometric properties have demonstrated its validity and reliability. It has a high internal consistency (Cronbach α ranging from 0.90 to 0.92).17

- none-

Spanish version of the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire (BISQ-E).18 It is a questionnaire developed for parents of children aged 5–29 months. It consists of 14 items, of which 10 assess sleep habits and four assess demographic characteristics; it includes four multiple-choice single-answer questions and 6 open-ended questions about the timing and duration of sleep. The questionnaire asks about where the child sleeps, in which position, the hours of nighttime sleep, hours of daytime sleep, number of nighttime awakenings, total time the child is awake at night, time it takes the child to fall asleep, how the child falls asleep, the time the child is put to bed and the parental perception of how well the child sleeps. We applied a threshold of 540min (9h) as the cutoff for nighttime sleep duration, as it was the multiple of 60 that was closest to the median and offered the most equitable group distribution. The questionnaire has been validated, with evidence of a significant correlation between BISQ scores and objective sleep measures obtained by actigraphy, and it is easy and quick to complete (completion time of 5−10min).19 This instrument is recommended by the Spanish clinical practice guideline for sleep disorders in children and adolescents for initial screening of sleep disturbances in early childhood at the primary care level.20

- none-

Questionnaire to collect demographic information on the toddler and parents, co-sleeping practices, room sharing, the use of pacifiers and feeding modality. Co-sleeping was defined as the child sleeping in the same bed as one or both parents. Parental age referred to the age at the time of questionnaire completion and calculated as the mean of the ages of both parents. The socioeconomic level of the family was categorized into groups based on the joint annual income of the couple: group 1 (≤€18 000), group 2 (€18 000 to €36 000) and group 3 (≥ €36 000).

During the routine healthy child checkup scheduled for age 2 years, parents were invited to participate in the study and, if they accepted, to provide informed consent.

After signing the informed consent form, they received three questionnaires (PSI-4-SF, BISQ-E and demographic questionnaire) to be completed on site by the father, mother or both.

Participating families received customary care per the standard protocol, and the study did not require any special tests or visits. Parents were asked to consider nights after which they did not need to wake the child to go to daycare, travel, etc.

We analyzed the following variables: total score on the PSI-4-SF and scores in its three subscales, sleep-related variables obtained through the BISQ-E, gestational age, weight percentile at age 2 years, previous history of hospitalization, parental age, infant feeding modality until age 6 months, duration of breastfeeding, duration of co-sleeping and room sharing during sleep, bedtime routine at least 6 days a week, family socioeconomic status and pacifier use.

Statistical analysisQuantitative data are expressed as mean and standard deviation if they were normally distributed based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and otherwise as median an interquartile range. Qualitative data are summarized as absolute frequency and percentage distributions. We assessed for potential significant associations between the total scale and subscale scores in the PSI-4-SF and the variables under study, calculating odds ratios by means of 2×2 contingency tables. We measured the association with the Pearson correlation coefficient. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with the software IBM SPSS, version 20.

ResultsThe sample included 109 families, of which 53.2% brought in a daughter and 46.7% a son. In 44% of cases, the mother completed the questionnaires, in 21.1% it was the father, and in 34.8% both parents did it together. A total of 25 families reported co-sleeping (22.9%), 16 (14.6%) reported sharing the bedroom without co-sleeping and 68 (62.3%) reported that the child slept in another room.

When it came to the toddler’s sleep, the median and interquartile range values were 500min (447.5–602.5) for the total nighttime sleep duration, 15min (5–60) for the time spent awake during the night, 1 (0–3) for the number of nighttime awakenings and 10min (8–20) for the time it took the child to fall asleep. The mean total score in the PSI-4-SF was 61.1 (SD, 12.3), while the mean subscale scores were 23.8 (SD, 3.2) for parental distress, 20.2 (SD, 3.9) for parent-child dysfunctional interaction and 21.5 (SD, 3.1) for difficult child.

The correlation coefficient (r) and coefficient of determination (R2) obtained for the correlation between the total PSI-4-SF score and the minutes of nighttime sleep, the minutes awake at night, the number of nighttime awakenings and the minutes of sleep latency were −0.478 (P=.001), R2=0.22; −0.237 (P=.07), R2=0.05; −0.344 (P=.005), R2=0.11 and −0.205 (P=.09), R2=0.05, respectively.

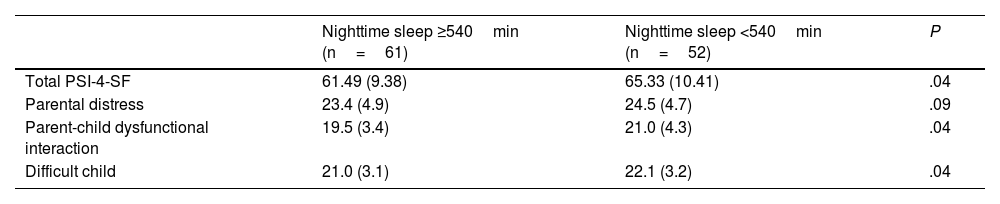

Table 1 presents the total and subscale scores in the PSI-4-SF in relation to whether the total nighttime sleep duration of the child was greater than or less than 540min.

Total and subscale PSI-4-SF scores in relation to the minutes of nighttime sleep in the toddler at age 2 years.

| Nighttime sleep ≥540min (n=61) | Nighttime sleep <540min (n=52) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total PSI-4-SF | 61.49 (9.38) | 65.33 (10.41) | .04 |

| Parental distress | 23.4 (4.9) | 24.5 (4.7) | .09 |

| Parent-child dysfunctional interaction | 19.5 (3.4) | 21.0 (4.3) | .04 |

| Difficult child | 21.0 (3.1) | 22.1 (3.2) | .04 |

Scores expressed as mean (SD) and compared based on the minutes of nighttime sleep with the Student t test, which yielded the P value for assessment of statistical significance.

Abbreviation PSI-4-SF: Parenting Stress Index-4-Short Form.

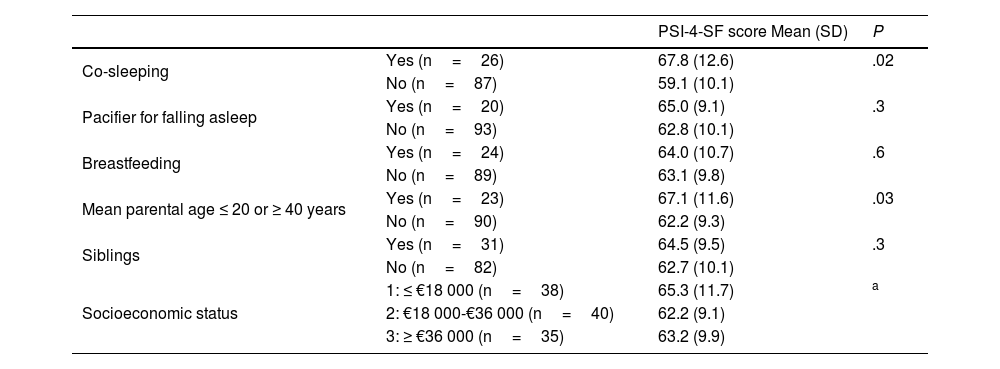

Table 2 presents the PSI-4-SF scores in relation to sleep and feeding practices and sociodemographic characteristics.

Score in the PSI-4-SF in relation to sleep-related variables, feeding modality and sociodemographic characteristics.

| PSI-4-SF score Mean (SD) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-sleeping | Yes (n=26) | 67.8 (12.6) | .02 |

| No (n=87) | 59.1 (10.1) | ||

| Pacifier for falling asleep | Yes (n=20) | 65.0 (9.1) | .3 |

| No (n=93) | 62.8 (10.1) | ||

| Breastfeeding | Yes (n=24) | 64.0 (10.7) | .6 |

| No (n=89) | 63.1 (9.8) | ||

| Mean parental age ≤ 20 or ≥ 40 years | Yes (n=23) | 67.1 (11.6) | .03 |

| No (n=90) | 62.2 (9.3) | ||

| Siblings | Yes (n=31) | 64.5 (9.5) | .3 |

| No (n=82) | 62.7 (10.1) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | 1: ≤ €18 000 (n=38) | 65.3 (11.7) | a |

| 2: €18 000-€36 000 (n=40) | 62.2 (9.1) | ||

| 3: ≥ €36 000 (n=35) | 63.2 (9.9) |

We calculated the statistical significance of the difference in means using the Student t test, except for the comparison of PSI-4-SF scores according to socioeconomic status, which was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA).

PSI-4-SF: Parenting Stress Index-4-Short Form.

Co-sleeping was associated with breastfeeding maintenance at age 2 years (odds ratio, 18.4; 95% CI, 5.9–56.8). We did not find a statistical association between co-sleeping and pacifier use, parental age, child sex, presence of siblings or socioeconomic status.

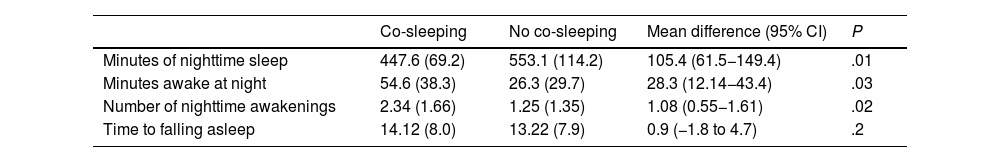

Table 3 describes the differences in minutes of nighttime sleep, minutes awake at night, number of awakenings, and minutes to fall asleep in relation to the practice of co-sleeping.

Characteristics of child’s sleep in relation to the practice of co-sleeping.

| Co-sleeping | No co-sleeping | Mean difference (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minutes of nighttime sleep | 447.6 (69.2) | 553.1 (114.2) | 105.4 (61.5−149.4) | .01 |

| Minutes awake at night | 54.6 (38.3) | 26.3 (29.7) | 28.3 (12.14−43.4) | .03 |

| Number of nighttime awakenings | 2.34 (1.66) | 1.25 (1.35) | 1.08 (0.55−1.61) | .02 |

| Time to falling asleep | 14.12 (8.0) | 13.22 (7.9) | 0.9 (−1.8 to 4.7) | .2 |

Sleep variables expressed as mean (SD). The mean difference obtained with the Student t test is presented with the corresponding 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance reported in the form of P values.

Parental stress increased with decreasing nighttime sleep duration in toddlers and with co-sleeping at age 2 years, as well as with a mean parental age of less than 20 or more than 40 years. On the other hand, co-sleeping was associated with a reduced duration of nighttime sleep, an increase in the time awake at night and more awakenings. To our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzes the association between parental stress, toddler sleep and co-sleeping at age 2 years.

As would be expected, parents of children with nighttime sleep problems report increased daytime somnolence affecting their daily lives, which translates to a negative perception of parenting in association with insufficient maternal sleep as well as higher levels of stress.21,22 This phenomenon is more prominent in mothers than in fathers, and infant sleep has been found to be a predictor of maternal sleep quality, mood, stress and fatigue.23 There is evidence suggesting that maternal mental health is associated with the perceived toddlers sleep quantity and quality, and that this association is mediated by maternal sleep duration.24 De Stasio et al. described the effect of the number of toddler nighttime awakenings on maternal stress, while paternal stress was more affected by the time required by toddlers to fall asleep.15 Our findings on the increase in parental stress in association with a reduced nighttime sleep duration in toddlers corroborated the results published by Tikotzky et al. and by Merril and Slavik, who reported higher levels of parental stress (measured with different methods) in association with sleep disturbances in the offspring, from the birth of the child, throughout childhood and even up to age 25 years.25,26

When we analyzed the subscales of the PSI-4-SF, we found differences in the parent-child dysfunctional interaction and the difficult child subscale scores based on the total minutes of nighttime sleep, based on which we may infer that the child’s insomnia has a more negative impact on the parent-child bond, parental expectations and parental perception of the child as problematic, with a lesser impact on the quality of the couple’s relationship or the perceived limitations in everyday life associated with parenting. These results support previous findings regarding improved parental perception of having a difficult child as well as more secure attachment of the toddler in relation to increased duration of nighttime sleep in the child.27,28

Parental age was the only analyzed socioeconomic factor that had a negative impact on parental stress. Individuals who become parents at an early age (due to inexperience, financial difficulties, etc) or at an advanced age (more or more serious health concerns, higher rate of postpartum depression) are more likely to experience higher levels of stress.29,30 We did not find evidence of socioeconomic status affecting stress, an association reported by other research groups in both developed and developing countries, probably attributable to the difference in the number of stressors, such as material difficulties and limited social support.31,32

Our results regarding the increase in parental stress associated with co-sleeping corroborate the findings of the study conducted in infants aged 3–6 months by Teti et al., who reported greater coparenting distress and less emotionally available mothering in families that co-slept.33 On the other hand, co-sleeping reinforces the negative association between decreased maternal sleep and perceived toddler sleep problems.24 It must be taken into account that our study assessed the impact of co-sleeping at a later stage (age 2 years), when the percentage of families that co-sleep is lower compared to earlier stages: 22.9%, slightly lower compared to the rate reported in Spain at age 1year (26%), with the only reported percentage for age 2 years (43.6%) corresponding to a study conducted in China.34,35 Furthermore, it is believed that the emotional state of parents returns to the pregestational baseline by two years post birth, making this a more appropriate time for the emotional assessment of parents.36

The reason that motivated the decision to co-sleep should be considered, for, if the choice to co-sleep was based on previous sleep problems in the child, the increase in parental stress could be due to the child’s insomnia, which would warrant the exclusion of the family from the study. In addition, co-sleeping could increase parental awareness of the toddler’s potential awakenings due to the increased physical proximity compared to the child sleeping in a different room, and it can also be a source of conflict between partners, thereby increasing parental stress.37 Still, there is evidence of a paradoxical decrease in the awareness of sleep problems in the offspring among caregivers who co-sleep with their toddler at age 2 years, despite evidence of a shorter sleep duration in these children.35

The impact of co-sleeping on children's sleep is a controversial subject, with published studies yielding heterogeneous results; polysomnography data have evinced a decreased duration of stages 3 and 4 of sleep and an increased duration of stages 1 and 2 of non-REM sleep in infants who co-sleep, but there is still no consensus among authors as to whether co-sleeping increases, decreases (as found in our study), or has no effect on the quality and quantity of children’s sleep.38–40

The data presented in this article are novel in that they analyze parental stress at a time for which there is a dearth of evidence (when the child is aged 2 years), linking parental stress to toddler sleep quality and sleep practices in the family. We found no studies in the literature examining the association between parental stress and co-sleeping at this age. Furthermore, the tool we used to measure parental stress (PSI-4-SF), which is universally used, validated, and easily accessible, has not been used in similar studies. Among the limitations of the study, we ought to highlight the assessment of sleep, in which no objective measures (such as actigraphy) were used, the potential bias in the detection of reduced sleep duration in children stemming from parental schedules and/or daycare attendance, even if parents were directed to consider nights when sleep would not be restricted on account of external factors, and the potential for participation bias, as families who experience problems related to their children’s sleep may be more willing to participate in a survey that assesses this aspect.

In conclusion, the findings of the study support a strong association between reduced child sleep duration at age 2 years and increased parental stress. In addition, the practice of co-sleeping was associated with increased parental stress and decreased sleep duration in the child. Extreme parental age (whether young or old) was also associated with a higher level of stress

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Previous meeting: this study was submitted for presentation as an oral communication at the 71st Congress of the Asociación Española de Pediatría.