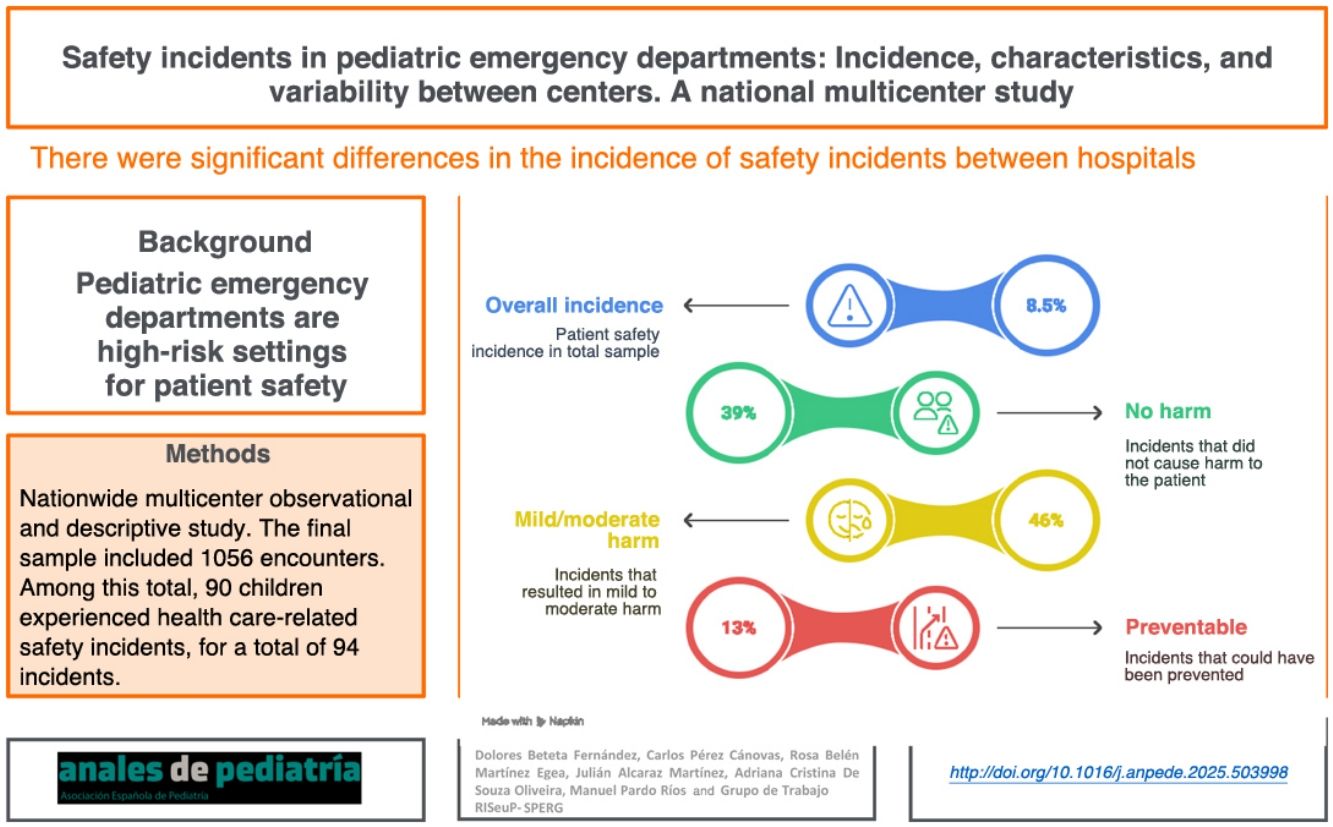

Pediatric emergency departments are high-risk environments for patient safety due to the workload, time pressure and clinical vulnerability of the population. However, there is limited evidence regarding the prevalence, characteristics and associated factors of safety incidents in this setting. Understanding these events is essential to design effective improvement strategies.

ObjectiveTo estimate the incidence of patient safety incidents in pediatric emergency departments, describe their characteristics and identify associated factors. Multicenter, observational and descriptive study based on retrospective chart review and structured incident reporting.

MethodsWe identified a total of 1102 pediatric patients treated in the emergency departments of nine Spanish hospitals during the second quarter of 2021 were identified. After excluding 49 patients who could not be reached for follow-up, the final sample included 1056 cases. Of these, 90 children experienced incidents related to healthcare, with a total of 94 incidents, as four patients experienced two incidents each. A previously validated tool was used to collect demographic, clinical and organizational data, as well as information on safety incidents. Results: The overall proportion of patients with at least one safety incident was 8.5% (95%CI: 6.0–9.0). Most incidents caused no harm (39%) or mild to moderate harm (46%), and 13% were deemed clearly preventable. Incidents mainly occurred during emergency care and were attributed to organizational, communication or human factors. There were significant differences between hospitals (P < .01), but we found no associations with shift, triage level, or mode of arrival. The hospital continued to be a significant predictor in the multivariate analysis.

ConclusionsPatient safety incidents in pediatric emergency departments are frequent and partly preventable. The variability observed between centers, which persisted after adjusting for the catchment pediatric population and staffing characteristics, suggests the influence of structural and cultural factors specific to each institution. Context-adapted institutional strategies need to be implemented to foster a proactive safety culture and effective risk management.

Los servicios de urgencias pediátricas poseen una complejidad significativa debido a la pelicularidad y vulnerabilidad de la población atendida, convertiendo a estos en entornos de alto riesgo para la seguridad del paciente. Sin embargo, la evidencia sobre la prevalencia, las características y los factores asociados a los incidentes de seguridad en este contexto sigue siendo limitada. Comprender estos incidentes es esencial para diseñar estrategias de mejora efectivas.

ObjetivoEstimar la incidencia de incidentes de seguridad del paciente en urgencias pediátricas, describir sus características e identificar posibles factores asociados. Estudio observacional, descriptivo y multicéntrico, basado en la revisión de historias clínicas y formularios estructurados de detección de incidentes.

MétodosSe identificaron 1102 pacientes pediátricos atendidos en los servicios de urgencias de nueve hospitales españoles durante el segundo trimestre de 2021. Tras excluir a 49 pacientes que no respondieron al seguimiento telefónico, la muestra final fue de 1056 casos. De ellos, 90 niños presentaron incidentes relacionados con la asistencia, sumando un total de 94 incidentes, ya que cuatro pacientes presentaron dos incidentes cada uno. Se utilizó un instrumento previamente validado para registrar datos demográficos, clínicos, organizativos y relacionados con el incidente.

ResultadosLa incidencia global de pacientes con al menos un incidente de seguridad fue del 8,5 % (IC95%: 6,0–9,0). El 39 % de los incidentes no causó daño, mientras que el 46 % generó daño leve o moderado. El 13 % se consideró claramente evitable. La mayoría se detectó durante la atención en urgencias y se atribuyó a causas organizativas, comunicativas o humanas. Se observaron diferencias significativas en la incidencia entre hospitales (p < 0,01), mientras que no se hallaron asociaciones con el turno, el nivel de triaje ni el modo de llegada. El hospital se mantuvo como variable predictora significativa en el análisis multivariante.

ConclusionesLos incidentes de seguridad en urgencias pediátricas son frecuentes y en parte evitables. La variabilidad observada entre centros, que persiste tras el ajuste por población pediátrica asignada y características del personal, sugiere la influencia de factores estructurales y culturales específicos de cada institución. Es necesario implementar estrategias institucionales adaptadas que promuevan una cultura de seguridad proactiva y una gestión eficaz de los riesgos.

Pediatric emergency departments (PEDs) are fast-paced health care settings with high workloads and a rapid patient flow where quick decision-making is required, circumstances that may pose a risk to patient safety.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines patient safety as “the absence of preventable harm to a patient and reduction of risk of unnecessary harm associated with health care to an acceptable minimum”2 and considers it a priority issue in public health on account of its direct impact on morbidity, mortality, avoidable disability and the use of health care resources.3

Patient safety results from a combination of organizational, human and cultural factors. Among them, a culture of safety has a direct impact on error reporting, institutional learning and the prevention of adverse events.4 The few studies conducted in pediatric emergency care settings in Spain have addressed specific aspects, such as medication errors5 or risk mapping.6 This highlights the knowledge gap on safety incidents in PEDs, despite the particularly vulnerable nature of pediatric patients and the technical and psychological complexity of their care.

Most studies in the literature have been conducted in non-acute hospital settings, using retrospective methods or reporting systems with a low sensitivity. Therefore, prospective multicenter studies are required to better characterize the frequency, nature, impact and preventability of incidents in pediatric acute care settings.7 Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional stressors in emergency care settings, potentially modifying clinical and organizational risk patterns.8

The aim of our study was to identify and describe patient safety incidents detected in the PEDs of several hospitals in Spain, analyzing their frequency, characteristics, causal factors, clinical impact and preventability. The results will allow us to establish priorities for improvement with the ultimate objective of increasing patient safety in the pediatric care setting.

Material and methodsThe study was conducted and reported in adherence to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for observational studies.9 Statistical results were reported following the SAMPL (Statistical Analyses and Methods in the Published Literature) guidelines.10

Study designWe conducted a multicenter, prospective, cross-sectional, observational and descriptive study focused on the identification and analysis of safety incidents in PEDs at the nationwide level in Spain.

SettingNine public hospitals of the National Health System of Spain, distributed across different autonomous communities, participated in the study. Participation was voluntary and supported by the Spanish Pediatric Emergency Research Group (RISeuP-SPERG) network, which facilitated the recruitment of centers by forwarding study information to pediatric emergency departments. Initially, 11 centers were expected to participate, but two withdrew due to the pandemic. All participating centers had PEDs that operated 24 h a day. Centers were included by convenience sampling, relying on the voluntary participation of professionals with previous training in patient safety and research experience. We recorded the number of health care professionals (pediatricians, nurses, assistants) on staff in each PED during the study period (Appendix B, Supplemental material 1). We calculated staff ratios per 1000 managed patients to allow comparisons between centers in relation to the European standard population of 2013 (Eurostat).11 To calculate the age-adjusted incidence rates (Appendix B, Supplemental material 2), we established the following age groups: <1 year, 1–4 years, 5–9 years, 10–14 years. The formula used for its calculation was: adjusted rate = Σ(Ri × Pi)/ΣPi, where Ri is the age-specific rate in group i and Pi the standard population in group i.

Population and inclusion criteriaThe study universe comprised all patients aged less than 14 years managed in the PEDs between April and June 2021. We identified 1102 patients, of who 49 did not complete follow-up, leaving a final sample of 1056 children. Of this total, 90 experienced at least one health care-related safety incident, with a total of 94 documented incidents, as four children experienced two incidents during the study period. We selected cases by opportunity sampling, stratifying by shift (morning, afternoon and night) and distributed randomly to ensure representativeness over time. We excluded patients who did not undergo any form of intervention or for whom it was not possible to obtain complete follow-up information.

Data collectionThere were two complementary phases in data collection: direct observation during the emergency care encounter, and follow-up after seven days, either by telephone or in person (if the patient was still hospitalized). This strategy made it possible to detect both incidents observed during the health care encounter, in real time, and those that manifested after discharge.

To collect the information, we used the version of the instrument developed from the data collection form of the ERIDA study12 validated and adapted for safety incident reporting in pediatric care settings.13 The questionnaire is structured in different sections to collect data on the sociodemographic characteristics of the patient, the characteristics of the health care encounter, the characteristics, clinical impact and degree of preventability of the incident, the contributing factors and whether or not the incident was documented in the health records.

Study variablesThe primary outcome was the incidence of safety incidents, defined as the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event or incident that could have led to harm during the health care encounter or the follow-up:

We also collected data on clinical variables (reason for PED visit, triage level, interventions performed), organizational variables (shift, day of the week, patient origin), and incident-related variables: type, severity, preventability, need for follow-up care and documentation in health record.

Preventability was assessed independently by two researchers using the criteria of the trigger tool applied in the Canadian Paediatric Adverse Events Study1 and classifying each incidence as “nonpreventable” “potentially preventable” or “definitely preventable”. The operational definitions used to define incidents can be found in section 3 of the Supplemental material (Appendix B).

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive analysis calculating absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for the main proportions. Since the objective of the study was strictly descriptive, we did not carry out any inferential analyses.

The statistical analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics software package, version 25 software (IBM Corp; Armonk, NY, USA), considering a percentage of missing data of less than 5% acceptable.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the coordinating center (code CEIC-ARX-2021/04). We obtained informed consent from parents or legal guardians and guaranteed confidentiality in accordance with Organic Law 3/2018 on the Protection of Personal Data and the Guarantee of Digital Rights.

ResultsDescription of the sampleThe mean (SD) age of the patients who experienced some form of health care-related incident was 3.7 (1.3) years, with an even sex distribution. The highest percentage of incidents occurred during the morning shift and most of the patients were self-referred. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic and health care encounter characteristics for patients who experienced safety incidents.

Sociodemographic and health care encounter characteristics in patients who experienced incidents.

| Variable | Categorya | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | >7 years | 46 | 48.9 |

| 1−3 years | 23 | 24.5 | |

| 3−7 years | 13 | 13.8 | |

| 1−12 months | 8 | 8.5 | |

| Newborn | 4 | 4.3 | |

| Sex | Male | 48 | 51.1 |

| Female | 46 | 48.9 | |

| Day of the week | Wednesday | 22 | 23.4 |

| Thursday | 20 | 21.3 | |

| Saturday | 15 | 16.0 | |

| Monday | 12 | 12.8 | |

| Friday | 11 | 11.7 | |

| Sunday | 9 | 9.6 | |

| Tuesday | 5 | 5.3 | |

| Shift | Morning | 33 | 35.1 |

| Night | 31 | 33.0 | |

| Afternoon | 30 | 31.9 | |

| Hospital | H. Sant Joan de Déu | 20 | 21.3 |

| H. Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca | 16 | 17.0 | |

| H. Son Llatzer | 15 | 16.0 | |

| H. Universitario Infanta Sofía | 10 | 10.6 | |

| H. Universitario La Paz | 10 | 10.6 | |

| H. General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | 5 | 5.3 | |

| H. Niño Jesús | 3 | 3.2 | |

| H. de Terrasa (Consorci Sanitari de Terrasa) | 2 | 2.1 | |

| Patient origin | Self-referral | 82 | 87.2 |

| Primary care/EMS | 12 | 12.8 |

Abbreviations: EM, Semergency medical services; H, hospital.

Of the 1054 patients included in the study, 90 (8.5%) experienced at least one safety incident during the emergency care visit or the subsequent follow-up. In most cases, only one incident was documented (95.6%), although some patients experienced two events (4.4%); there were no cases with more than two incidents. The overall incidence was 8.5% (95% CI, 6.0%–9.0%).

Most incidents were detected during the health care encounter at the PED, with no documented cases of incidents occurring exclusively during follow-up. With regard to type, incidents were most frequently related to general care, followed by incidents related to the physical examination, diagnosis and treatment. Table 2 shows the distribution of incidents by frequency, timing and type.

Frequency, nature, timing, severity and preventability of incidents.

| Variable | Categorya | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health care | No impact | 65 | 69.1 |

| Repeat visit or referral | 9 | 9.6 | |

| Required observation | 8 | 8.5 | |

| Additional testing | 6 | 6.4 | |

| Medical or surgical treatment | 5 | 5.3 | |

| Harm | Psychological/moral | 47 | 50.0 |

| Physical harm not requiring treatment | 18 | 19.1 | |

| + observation/testing | 16 | 17.0 | |

| Physical harm requiring treatment | 12 | 12.8 | |

| Effect | Disease-related harm | 4 | 4.3 |

| Slight prolongation | 3 | 3.2 | |

| Significant prolongation | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Minimal prolongation | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Preventability | Evidently preventable | 41 | 43.6 |

| Unlikely to be preventable | 18 | 19.1 | |

| Likely preventable | 11 | 11.7 | |

| Nonpreventable | 10 | 10.6 | |

| Could not be determined | 10 | 10.6 | |

| Clear failure | No | 47 | 50.0 |

| Yes | 46 | 48.9 | |

| Impact | No impact | 36 | 38.3 |

| Had impact, caused no harm | 31 | 33.0 | |

| Mild harm | 27 | 28.7 |

Specific causal factors were identified in most of the analyzed safety incidents. The most frequent were those related to organizational and administrative aspects (23%), followed by communication failures (18%), human factors related to individual health care workers (17%) and teamwork issues (13%).

Less frequently, we identified factors related to clinical documentation, insufficient clinical knowledge, available material resources and care transition processes. There were also 13 causal factors that were present in a single case each, amounting to 13.8% of the total incidents.

Patients who experienced safety incidents were significantly younger than those who did not experience any (mean [SD], 3.7 [1.3] vs 4.2 [1.8] years; P = .018). There were no significant differences in sex, triage level, shift, or patient origin.

In approximately one-fifth of cases (20%), adequate classification of the causal factor was not possible due to incomplete records or a lack of standardized coding at the time of reporting.

Comparison of centers and health care variablesWe found statistically significant differences in the incidence of safety incidents among the participating hospitals (P = .004), hinting at the potential influence of center-specific organizational, structural or cultural factors (Table 3). The variation between centers ranged from 1.6% to 15.5%, despite the fact that all of them applied the same inclusion criteria and data collection methodology. We did not find a significant correlation between the ratio of health care staff per 1000 patients (Appendix B, Supplemental material 1) and the incidence of adverse events (r = −0.18; P = .642), which suggests that other organizational factors may have a greater impact than staffing levels.

Comparison of incidents between hospitals.

| Hospital | Number of incidents | Preventable (%) | Physical harm (%) | Clear error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 31.2 | 62.5 | 43.8 |

| 3 | 10 | 40.0 | 30.0 | 40.0 |

| 4 | 2 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| 5 | 20 | 50.0 | 20.0 | 55.0 |

| 6 | 5 | 60.0 | 0.0 | 60.0 |

| 7 | 3 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 33.3 |

| 8 | 10 | 20.0 | 10.0 | 30.0 |

| 9 | 15 | 66.7 | 26.7 | 60.0 |

| 10 | 13 | 38.5 | 38.5 | 53.8 |

Patients who experienced safety incidents were significantly younger than those who did not experience any (mean [SD], 3.7 [1.3] vs 4.2 [1.8] years; P = .018). There were no significant differences between patients who did and did not experience incidents in terms of sex, triage level, shift or patient origin (Table 4). On the other hand, there were no significant differences in the incidence of incidents based on shift (P = .345) or patient origin (P = .445). These findings support the hypothesis that structural factors or those related to safety culture at the level of the organization may play a greater role than particular circumstances or conditions in care delivery.

Comparison of the profiles of patients who did and did not experience incidents.

| Variable | Incidents (n = 90) | No incidents (n = 966) | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 3.7 (95% CI, 3.4−4.0) | 4.2 (95% CI, 4.1−4.3) | .018 | – |

| Male sex | 48 (53.3%) | 498 (51.6%) | .752 | 1.07 (0.71−1.62) |

| Triage level | .796 | |||

| Level 1−2 | 12 (13.3%) | 115 (11.9%) | 1.13 (0.59−2.18) | |

| Level 3 | 45 (50.0%) | 495 (51.2%) | 0.95 (0.63−1.44) | |

| Level 4−5 | 33 (36.7%) | 356 (36.9%) | 0.99 (0.65−1.52) | |

| Shift | .345 | |||

| Morning | 33 (36.7%) | 312 (32.3%) | 1.21 (0.78−1.89) | |

| Afternoon | 30 (33.3%) | 338 (35.0%) | 0.92 (0.59−1.45) | |

| Night | 27 (30.0%) | 316 (32.7%) | 0.88 (0.56−1.39) | |

| Patient origin | .445 | |||

| Self-referral | 78 (86.7%) | 862 (89.2%) | 0.77 (0.42−1.41) | |

| Referred | 12 (13.3%) | 104 (10.8%) | 1.27 (0.68−2.38) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Similarly, there were no significant differences when we compared the incidence of incidents based on shift (morning, afternoon or night). The clinical severity of the patient on arrival, established based on the triage level, was also not associated with an increased probability of experiencing a safety incident (P = .796).

We observed a statistically significant association between the impact of the incident and its preventability (P = .003). There was a higher proportion of incidents considered to be preventable, especially of those with clear evidence of being preventable, among the incidents with greater clinical impact. Fig. 1 provides a graphical representation of this association.

There were no significant differences in pretriage times (P = .284) or care time (P = .670) between preventable and nonpreventable incidents. However, the total time to discharge was significantly shorter in the group of preventable incidents (P = .014), which could reflect a lesser clinical complexity or faster resolution in this type of event. Fig. 2 shows the comparison between the two groups.

DiscussionThis is the first study on patient safety incidents in the pediatric emergency setting conducted in Spain with a prospective design, analyzing organizational and clinical factors, the harm caused by the incident and its preventability. In Spain, there have been previous studies specifically focused on medication errors in the PED setting.5,14,15 When it came to the proportion of patients with incidents, it was higher (8.5%) compared to other studies conducted in Spain5,15 (although those focused specifically on medication errors) and abroad.16,17 Still, most incidents did not result in serious harm. More than 40% had some form of clinical impact, evincing the imperative need for a culture of safety to improve patient safety in complex pediatric care.18

Our results show that most incidents were detected during the emergency care encounter and not in the subsequent follow-up, which was consistent with other studies,5,15,19 underscoring the value of direct observation as a detection tool.20 As regards the type of incident, there was a predominance of errors related with general care and communication, factors that have been previously identified as prevalent in care settings with heavy workloads and numerous clinical interactions.21

The finding of a higher probability of incidents in younger patients is consistent with their greater physiological vulnerability and the intrinsic difficulties in their clinical assessment. This association highlights the need to exert extreme caution in the management of infants and preschool children, with implementation of age-specific protocols and specialized training for health care staff.

One of the most relevant contributions of this study is the significant intercenter variation in the incidence of safety events, with differences ranging from 0.8% to 14%. This dispersion did not seem to be attributable to differences in shift, triage level or patient origin, suggesting that there may be specific structural, organizational or cultural factors that modulate the risk of error in at the level of the institution.21 This finding was consistent with the previous evidence linking safety culture with the frequency of adverse events and the likelihood of incident reporting.17,22

This finding was confirmed in the bivariate analysis, where the hospital remained a factor significantly associated with the probability of an incident, even after adjusting for shift, triage level and patient origin. This supports the hypothesis that broad structural and institutional factors have a greater impact than individual health care variables on the occurrence of errors.

We did not find statistically significant associations between the occurrence of incidents and triage level, contradicting the common assumption that more complex patients are at increased risk. The absence of this correlation has also been reported in multicenter studies in adults, in which errors tended to depend more on the health system than clinical severity.21 This finding persisted even after adjusting for other clinical and organizational variables, suggesting that the risk of safety incidents does not depend as much on initial acuity as on health care setting- and process-related factors.17,18,21 Contrary to those variables, the comparison of patients who experienced incidents versus those who did not revealed a significant difference in age, with a younger age in the former (Table 4). This finding is consistent with the greater physiological vulnerability and the intrinsic difficulties in their clinical assessment, especially in infants and preschoolers. The association between younger age and an increased risk of safety incidents evinces the need to implement specific safety protocols and specific training for health care professionals to optimize the management of patients in these age groups.

With regard to clinical impact, it is worth noting that nearly half of the incidents resulted in mild or moderate harm, which underscores the need for proactive detection systems, especially in a pediatric care setting where the margin of safety is narrower. Furthermore, one in five incidents was considered clearly preventable, a proportion consistent with similar studies, showing that there are clear opportunities for improvement in routine clinical practice.15,17 In addition, we observed that incidents that were considered preventable had shorter resolution times, which could indicate a lesser clinical complexity or faster resolution in situations in which there was a clear opportunity for improvement.

These findings were consistent with those of recent studies, like one conducted in a single center in Spain with an incidence of 12.3% and a proportion of incidents considered preventable of 78.6%.23 The same study also showed that children who experienced incidents had undergone more examinations and procedures. These findings do not suffice to establish an association between patient acuity and the risk of incidents conclusively. Although some results suggest a higher frequency of errors in more complex cases, others contradict the not-infrequent assumption that more severely ill patients are at increased risk. This suggests the need of exploring other organizational and health care-related factors. Our study, which was larger and conducted in multiple centers, confirmed and expanded those findings in a more representative cohort.

Finally, the analysis of the causes showed that organizational, human and communication factors were the most relevant. These factors coincide with the latent factors in the models described by Reason, which support the importance of intervening on the structure of the system to improve patient safety beyond the individual behavior of professionals,24 and the Donabedian model that proposes a multifactorial, ongoing, unbroken-chain approach to the evaluation of health care quality based on general systems theory25 which, in turn, has patient safety as its core dimension. Last of all, the study was conducted over a short period of time and following the COVID-19 pandemic, which could have affected patient volume and the perception of risk by health care professionals.

Study limitationsThere are some limitations to this study that should be taken into account. First, its descriptive design and the lack of multivariate analysis precluded the establishment of causal relationships between variables. Second, although the data collection instrument had been validated, there may have been interobserver variability due to the collection of data in multiple centers, despite the prior training of the participating health care professionals. We can also not rule out the possibility of under-recording or reporting bias, especially in centers with a lower incidence, which could reflect differences in reporting culture rather than in the actual occurrence of incidents. Differences between centers in the catchment population and health care staff characteristics could affect the comparability of the results, although the adjustment based on the European standard population partially mitigates this limitation.

Future lines of researchFuture studies should delve deeper into the structural and cultural factors that explain the variability between centers and prospectively analyze the association between certain health care processes and the occurrence of incidents. It would be useful to integrate qualitative analyses to explore barriers to reporting and the organizational context. Likewise, the application of mixed methodologies and the use of digital surveillance tools could improve the early detection of adverse events. Finally, it would be interesting to evaluate the impact of specific patient safety interventions on the incidence rate of incidents in pediatric emergency departments.

ConclusionsSafety incidents in pediatric emergency departments are relatively common, and, while most do not cause serious harm, a significant proportion are potentially preventable. The observed variation between centers, which persisted even after adjusting for the pediatric catchment population and staffing level, supports the influence of center-specific structural and cultural factors in the occurrence of these events. These findings underscore the need for proactive institutional safety strategies, tailored to each care setting, to promote early detection, systematic reporting and organizational learning from errors.

FundingThe study was funded through the 2019 research grant of the by the Spanish Pediatric Emergency Research Group (RISeuP-SPERG), sponsored by the SEUP, and extended in time on account of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to this study. The study was supported bythe Spanish Pediatric Emergency Research Group (RISeuP-SPERG), which provided logistic support and a grant.

This study conducted in collaboration with a multicenter working group with participation of the following health care professionals from different pediatric emergency departments across Spain. All of them are part of the research team and actively contributed to the development and implementation of the study:

Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid): Ana Martínez Serrano, Carmen Isabel Alonso García, Begoña de Miguel Lavisier; Hospital de Terrassa-Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa (Terrassa): Abel Martínez Mejías, Milaydis María Martínez Montero, Ana María Romero Mármol; Hospital Sant Joan de Déu (Barcelona): Vanessa Arias Constanti, David Muñoz Santanach, Elisabet Rife Escudero Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (Madrid): Gloria Guerrero Márquez, Blanca Collado González, Clara Ferrero García-Loygorri; Hospital Niño Jesús (Madrid): Javier Barroso Martínez; Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía (San Sebastián de los Reyes, Madrid): Patricia Lorenzo Rodelas, Alejandra Flores Lafora, Ane Plazaola Cortázar; Hospital Son Llàtzer (Palma): Beatriz Riera Hevia, Joana María Alba Mateu, Catalina Verónica Serra Ejgird; Hospital Arnau de Vilanova (Lleida): Judith Ángel Sola and Marina Espigares Salvia.