In recent years, there has been growing interest in environmental health and, in particular, in endocrine disruptors, also known as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). Endocrine disruptors are exogenous substances that interfere with the normal function of hormones and can have an impact on health. This growing social interest—which is even reflected in search metrics—is just the tip of the iceberg of the knowledge generated through decades of research. In 1962, the publication of Silent Spring, a book by Rachel Carson, was a milestone in bringing attention to the impact of pesticides on wildlife and humans, from which point numerous studies have been added to the scientific literature on the subject.

These studies highlight the global reach of chemical pollution, which spreads to remote areas and is integrated into everyday life. Endocrine disruptors can be found in food and food packaging, water, personal care and household cleaning products, household items, fabrics and upholstery, electronic products, medical equipment, pesticides and in the air, both indoors and outdoors. The detection of contaminants of emerging concern in Antarctic waters1 is a clear example of how this is not a problem restricted to a given region or time span. Many of these substances, initially designed for a beneficial purpose (improving crop yields, insulating us from cold temperatures, humidity, etc), have turned out to be harmful to our health, with highly variable manifestations, both in terms of symptoms and the latency period between exposure and the onset of the effect, which makes them difficult to study. Their effects on living beings, including humans, can be particularly severe during vulnerable stages of life such as pregnancy, childhood or puberty, when a combination of biological and socioeconomic factors increases risk and reduces the capacity to protect against them. For this reason, pediatricians have a fundamental role in promoting primary prevention from the earliest stages of life.

What do we mean by endocrine disruptors and why do they pose a challenge for research?The World Health Organization defines endocrine disruptor as “an exogenous substance or mixture that alters function(s) of the endocrine system and consequently causes adverse health effects in an intact organism, or its progeny, or (sub)populations.”2 Their study is complex due to several factors: they have effects at very low doses (usually in the range of parts per trillion or billion) and frequently exhibit nonmonotonic dose-response curves (U- or inverted U-shaped curves), which means that stronger effects may occur at lower rather than higher doses,3 in addition to significant variation in the time elapsed between exposure and effect.

Furthermore, there are sensitive windows in human development (gestation, childhood, adolescence) when an increased vulnerability to the effects of EDCs amplifies their impact, since the endocrine system plays a key role in the healthy development of organs and its dysfunction during these periods can have a larger or more lasting impact.

In addition, due to their ubiquitous presence, exposure to EDCs usually occurs as a mixture of multiple compounds at the same time (cocktail effect), with potential additive or synergistic effects. Some EDCs are also persistent and bioaccumulative, meaning that they accumulate in the body and can have an effect even long after exposure. Compounds stored in maternal adipose tissue can be transmitted to the offspring during pregnancy and through breastmilk. Nonmonotonic dose responses challenge traditional toxicological approaches based on linear dose-response relationships and highlight the need to develop updated assessment models.

Mechanisms of action and affected endocrine axesEndocrine disruptors can mimic, antagonize or modulate hormone activity by binding membrane or nuclear receptors, altering the synthesis, transport, metabolism and clearance of hormones or modulating the expression of receptors and cofactors. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal, hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axes are the main described targets. Moreover, this interference can affect neurodevelopmental, energy metabolism, immunity and fertility pathways, with a variable latent period, so that the effects can manifest years or decades after the initial exposure. These effects could even manifest in subsequent generations through epigenetic changes, affecting the offspring of exposed individuals.

Evidence on child health: from the plausible to the probableThe pediatric and public health scientific literature on EDCs has grown from hypothetical associations to a consistent body of epidemiological and experimental evidence. Currently, multiple studies document the association between early exposure to EDCs and a significant increase in the incidence and risk of various symptoms and diseases.

When it comes to the reproductive system, exposure to phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA) and organochlorine pesticides has been associated with alterations of spermatogenesis and an increased risk of testicular dysgenesis, precocious puberty and ovarian dysfunction. In the field of neurodevelopment, prenatal exposure to various EDCs, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), flame retardants, organophosphates, BPA and phthalates has been associated with lower IQ and an increased prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder, with a greater impact in the context of socially vulnerability. Certain “obesogenic” compounds such as BPA, organotin compounds, perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs) and phthalates disrupt adipogenesis and glucose homeostasis, increasing the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, PFAs, PCBs, phthalates and phenols interfere with the synthesis and transport of thyroid hormones, which can affect brain development in very early life stages as well as basal metabolism. Lastly, there is evidence suggesting that certain pesticides and PCBs modulate the immune response, increasing the susceptibility to infection and the risk of autoimmune diseases in exposed individuals.4

In conclusion, research on EDCs requires an integrative approach combining clinical medicine, epidemiology, exposomics and molecular toxicology with advanced statistical tools and emerging technologies to enable a comprehensive and innovative approach capable of generating solid evidence to support effective regulation for the protection of public and environmental health.

From this perspective, pediatricians have a responsibility to protect the health of the most vulnerable populations during critical stages of development. The particular sensitivity and exposure of children reinforce the need to establish primary prevention measures from the beginning of life, guided by the best available evidence and the nonmaleficence principle, avoiding inaction in situations where there is uncertainty.

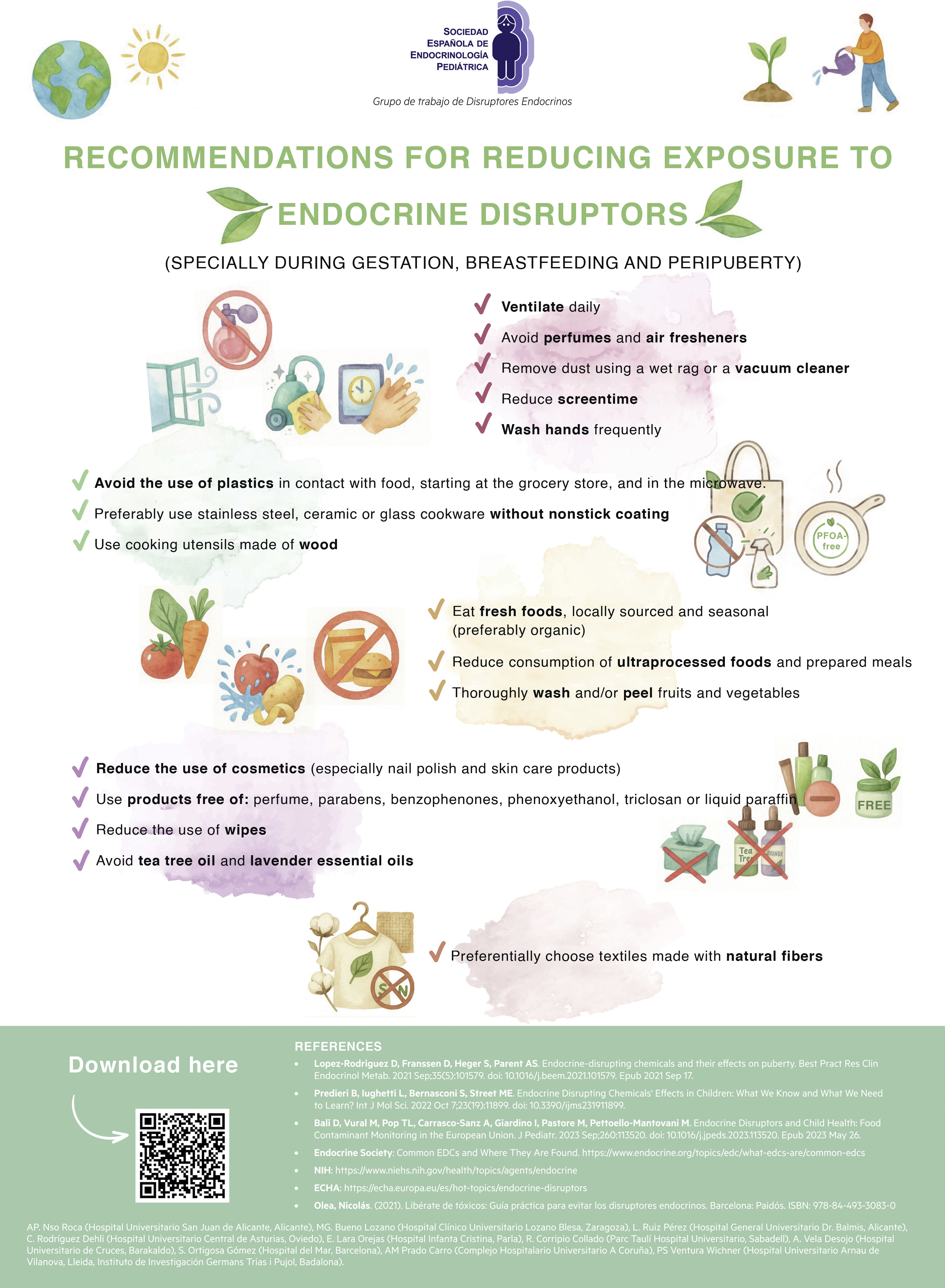

In this spirit, the Working Group on Endocrine Disruptors of the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología Pediátrica (SEEP, Spanish Society of Pediatric Endocrinology) has developed specific recommendations to reduce exposure to EDCs during childhood.5 These recommendations, summarized in Fig. 1 and accessible through the provided QR code, constitute a practical tool so that pediatricians, families and educators can implement simple changes with an impact in the short, medium and long term.

Recommendations for reducing exposure to endocrine disruptors.5

This project did not require any funding.

We want to thank the members of the Working Group on Endocrine Disruptors of the SEEP for their valuable contributions and commitment to the development of this project.

Sandra Ortigosa Gómez (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona), Ana Pilar Nso Roca (Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante, Alicante), Lorea Ruiz Pérez (Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis, Alicante), Raquel Corripio Collado (Parc Taulí Hospital Universitario, Sabadell), Ana Cristina Rodríguez Dehli (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo), Emma Lara Orejas (Hospital Infanta Cristina, Parla), Amaya Vela Desojo (Hospital Universitario de Cruces, Barakaldo), M. Gloria Bueno Lozano (Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza), Ana María Prado Carro (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña), Paula Sol Ventura Wichner (Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida, Instituto de Investigación Germans Triasi Pujol, Badalona).

Meeting presentation: the leaflet of recommendations to prevent exposure attached to this article was presented at the 47th Congress of the Sociedad de Endocrinología Pediátrica (SEEP); May 28–30, 2025; Madrid, Spain; and can be found in the website of the SEEP at: https://www.seep.es/images/site/pacientes/Exposicion_Disruptores_SEEP_2025.pdf (accessed 13/08/2025).

Appendix A lists the names of the members of the Working Group on Endocrine Disruptors of the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología Pediátrica (SEEP).