Toddler's fracture is an accidental spiral tibial fracture, characteristic of the early childhood. The objective of this study is to determine the incidence and current diagnosis and management of this disorder.

Patients and methodsA retrospective study was conducted on a sample of patients aged 0–3 years diagnosed with a toddler's fracture in a tertiary hospital between years 2013 and 2017.

ResultsA total of 53 patients were registered (10.6 cases per year). The median age was 2 years, with a slight male predominance. The initial radiograph was normal in 24.5% of patients. With the initial approach, 69.8% of patients were diagnosed with fracture, 11.3% with suspected fracture, and 18.9% with contusion. A follow-up was required in 22% through a control test, using radiographs in 10 patients (pathological 90%), and ultrasound in 5 (pathological 80%, 3 of them with normal initial radiography). The large majority (80.8%) of the patients were immobilised with a cast, while flexible immobilisation or non-immobilisation was used in 19.2%. Complications were found in a 21.4% of patients immobilised with splint, mainly skin injuries (19%). These were more frequent in this group than in those that were not immobilised (21.4% vs. 0%, P=.006); with no significant differences in time to weight-bearing.

ConclusionsRadiography has a limited sensitivity for the diagnosis of toddler's fracture. In the group of patients with normal radiography, the use of ultrasound can be helpful to the diagnosis and avoid additional radiation. Even though the most common treatment continues to be immobilisation with a splint, the alternative without rigid immobilisation does not seem to give worse results, even with lower morbidity associated with the treatment.

La fractura de los primeros pasos o fractura de toddler es una fractura espiroidea de tibia propia de la primera infancia. El objetivo es analizar su incidencia y el manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico actual.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo de los pacientes de 0 a 3 años diagnosticados en un hospital terciario entre los años 2013 y 2017.

ResultadosRegistrados 53 pacientes (10,6 casos/año), con una mediana de edad de 2 años y ligero predominio masculino. La radiografía inicial resultó normal en el 24,5%. Con la aproximación inicial, el 69,8% de los pacientes se diagnosticaron de fractura, el 11,3% de sospecha de fractura y el 18,9% de contusión. El 22% precisaron prueba de control; 10 radiografía (patológica 90%) y 5 ecografía (patológica 80%, 3 de ellos con radiografía inicial normal). El 80,8% de los pacientes se inmovilizaron con férula frente al 19,2% en los que se realizó inmovilización flexible o no inmovilización. Se encontraron complicaciones en el 21,4% de los pacientes inmovilizados con férula, fundamentalmente úlceras por presión (19%), que fueron más frecuentes en este grupo que en los no inmovilizados (21,4 vs. 0%; p=0,006), sin diferencias significativas en cuanto a tiempo hasta carga.

ConclusionesLa radiografía simple tiene una sensibilidad limitada para el diagnóstico de la fractura de los primeros pasos. En el grupo de pacientes con radiografía normal el uso de ecografía puede contribuir al diagnóstico y a evitar radiación adicional. Aunque el tratamiento más común de esta fractura sigue siendo la inmovilización con férula, la alternativa sin inmovilización rígida no parece obtener peores resultados, incluso parece presentar menor morbilidad asociada al tratamiento.

Toddler's fracture, also known as obscure tibial fracture or childhood accidental spiral tibial (CAST) fracture, is a fracture characteristic of early childhood (with a peak incidence between ages 9 months and 3 years). It is a spiral undisplaced fracture usually following a banal traumatic event, and results from low-energy torsion forces on a bone that is not accustomed to weight bearing. The diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, and may be complex due to several factors, such as the age of the patient, the frequent absence of perceivable changes or warmth in the skin, difficulty establishing the occurrence of the traumatic event and difficulty identifying the source of pain during the examination. The X-ray is the gold standard of diagnosis, although the fracture may be undetectable in a significant percentage of cases and only become evident 7–10 days post injury when sclerosis or a periosteal reaction develops in the area.1–7 Some authors have recently started to propose the use of ultrasound as an alternative imaging test.8 Since radiological diagnosis is not always possible, any cases of young children with a normal radiograph that present with acute limping or refusal to walk should be considered possible cases of toddler fracture if there is no evidence of infection (the differential diagnosis includes arthritis/osteomyelitis). There is no established standard of care, but treatment is based on analgesia and immobilisation, usually with a cast or splint, unloading the limb from weight-bearing forces.

Although this is a relatively common complaint, few recent studies have assessed the management of these fractures in emergency care settings in Spain. The objectives of our study were to establish the incidence of toddler's fracture in our population, assess the classical criteria for clinical diagnosis, assess the current use of the different diagnostic tools available, compare the management of patients with radiologically confirmed fracture versus patients with a clinical diagnosis and describe the treatments used, comparing outcomes and the incidence of complications based on the treatment.

Study sample and methodsWe conducted a retrospective and descriptive study of patients aged 0–3 years with toddler's fracture managed in the Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (HUMV) over a period of 5 years (2013–2017).

The Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla is a tertiary care hospital and the referral hospital for the paediatric population of the region of Cantabria in Spain (approximately 72,000 children aged less than 16 years). The hospital has a paediatric emergency department that manages approximately 44,000 emergency visits per year. All patients that receive a diagnosis of fracture in the emergency department are referred to the paediatric orthopaedics unit.

We identified cases by reviewing the electronic health records based on the recorded diagnoses, including all patients aged less than 4 years with a diagnosis of fracture in a lower extremity, more specifically those with a diagnosis of tibial fracture described as “oblique”, “spiral”, “diaphyseal”, “undisplaced” or “toddler's fracture”. We excluded cases secondary to bone disorders (such as osteogenesis imperfecta), of displaced fracture or of multiple fracture.

We collected data on age, sex, mechanism of injury, clinical manifestations and findings of physical examination, radiological diagnosis, delay in diagnosis, immobilisation strategy, variations in treatment, outcomes and complications.

We performed the statistical analysis with the software SPSS version 20.0. We used the chi square test to compare categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test to compare quantitative variables. For every test, we defined statistical significance as a P-value of less than 0.05.

ResultsWe identified 53 cases in the period under study, which corresponded to an incidence of 10.6 cases/per year and a prevalence of 0.24 cases per 1000 emergency department visits.

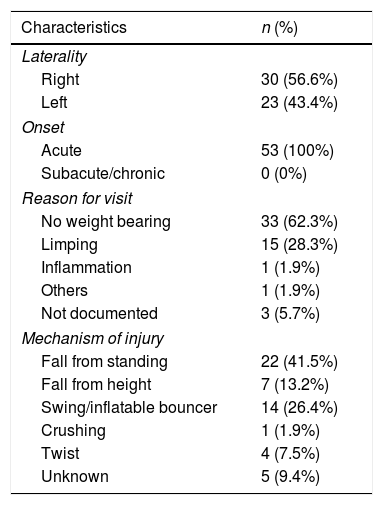

The median age at diagnosis was 2.04 years (IQR, 1.36–2.69). We found a slight predominance of the male sex (58.5%). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample in terms of the clinical presentation. We found similar proportions of fractures in the right and the left extremities. Most patients were brought to the emergency department due to an avoidance of weight bearing or to limping, usually resulting from a witnessed or reported traumatic event, although in 9.4% the mechanism of injury remained unknown. Low-energy trauma was the most frequent mechanism of injury (75.4%), including falls from standing, injuries related to the use of swings or inflatable bouncers and twists. High-energy mechanisms such as falls from heights or crushing were less frequent (15.1%). Physical abuse or violence was not suspected as the mechanism of injury in any case.

Presenting features at time of emergency department visit.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Laterality | |

| Right | 30 (56.6%) |

| Left | 23 (43.4%) |

| Onset | |

| Acute | 53 (100%) |

| Subacute/chronic | 0 (0%) |

| Reason for visit | |

| No weight bearing | 33 (62.3%) |

| Limping | 15 (28.3%) |

| Inflammation | 1 (1.9%) |

| Others | 1 (1.9%) |

| Not documented | 3 (5.7%) |

| Mechanism of injury | |

| Fall from standing | 22 (41.5%) |

| Fall from height | 7 (13.2%) |

| Swing/inflatable bouncer | 14 (26.4%) |

| Crushing | 1 (1.9%) |

| Twist | 4 (7.5%) |

| Unknown | 5 (9.4%) |

Percentage distribution of patient characteristics in terms of laterality, reason for emergency department visit and mechanism of injury.

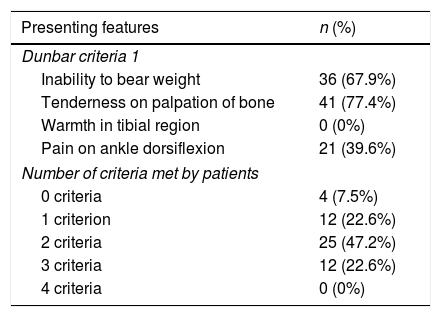

On examination, the most frequent feature was pain in the tibia on palpation (77.4%), although pain on ankle dorsiflexion was found in 39.6% of patients. Signs of inflammation such as warmth and redness were not present in any case. Axial compression was applied or documented in the assessment of very few patients (1.9%). Most patients presented with at least partial refusal to bear weight (94.3%); with total refusal in 67.9% of cases. Table 2 presents the criteria proposed by Dunbar et al. for the diagnostic examination.1

Examination criteria proposed by Dunbar.

| Presenting features | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Dunbar criteria 1 | |

| Inability to bear weight | 36 (67.9%) |

| Tenderness on palpation of bone | 41 (77.4%) |

| Warmth in tibial region | 0 (0%) |

| Pain on ankle dorsiflexion | 21 (39.6%) |

| Number of criteria met by patients | |

| 0 criteria | 4 (7.5%) |

| 1 criterion | 12 (22.6%) |

| 2 criteria | 25 (47.2%) |

| 3 criteria | 12 (22.6%) |

| 4 criteria | 0 (0%) |

Percentage distribution of the number of criteria met by patients.

The diagnostic tests used for the initial diagnosis were anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the tibia (performed in 98.1% of the patients) and, in a single rare case, an ultrasound scan (1.9% of total cases). The radiographic findings were normal in 13 patients (24.5%). The most common type of fracture was of the distal third of the tibia (54.7%), followed by fracture of the middle third (17%), while fracture of the proximal third was rare (1.9%). The single ultrasound scan performed for initial diagnosis revealed a fracture in the middle third.

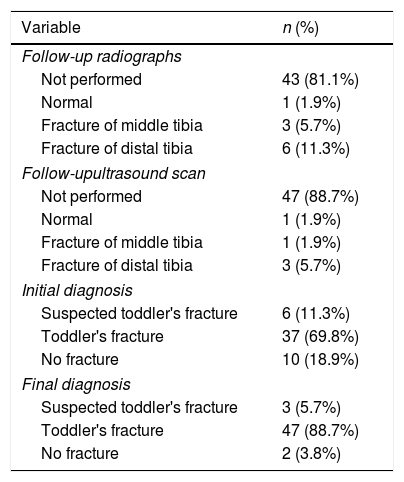

The initial evaluation resulted in diagnosis of toddler's fracture in 69.8% of the patients, of suspected fracture in 11.3% and of traumatic injury or bruising in 18.9%. Of all patients, 83% were referred to the traumatology department for assessment after the initial evaluation in the emergency department. In 12 patients (22.6%), a second evaluation with additional tests within 2 weeks from the initial evaluation was necessary for diagnosis, with performance of follow-up X-rays in 7 (58.3%), of ultrasound examination in 2 (16.6%) and both tests in 3 (25%); Table 3 summarises the findings of these tests. After this second evaluation, 88.7% of patients had a confirmed diagnosis of fracture, 5.7% a diagnosis of suspected fracture and 3.8% a diagnosis of traumatic injury or bruising. One of the patients was lost to follow-up because the patient had been transferred from a different region in Spain.

Radiological tests used during the follow-up and initial and final diagnosis of patients, expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Follow-up radiographs | |

| Not performed | 43 (81.1%) |

| Normal | 1 (1.9%) |

| Fracture of middle tibia | 3 (5.7%) |

| Fracture of distal tibia | 6 (11.3%) |

| Follow-upultrasound scan | |

| Not performed | 47 (88.7%) |

| Normal | 1 (1.9%) |

| Fracture of middle tibia | 1 (1.9%) |

| Fracture of distal tibia | 3 (5.7%) |

| Initial diagnosis | |

| Suspected toddler's fracture | 6 (11.3%) |

| Toddler's fracture | 37 (69.8%) |

| No fracture | 10 (18.9%) |

| Final diagnosis | |

| Suspected toddler's fracture | 3 (5.7%) |

| Toddler's fracture | 47 (88.7%) |

| No fracture | 2 (3.8%) |

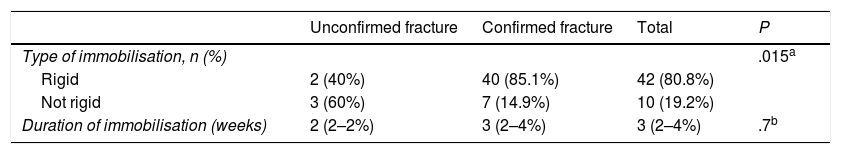

When it came to treatment, 88.7% of patients received prescriptions for analgesia with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (ibuprofen). As for the use of immobilisation (Table 4), of all patients with nonconfirmed suspected fracture, 60% were managed conservatively without rigid immobilisation, compared to immobilisation with a cast in 85.1% of patients with confirmed fracture. Overall, 80.8% of patients were managed with immobilisation with a rigid cast compared to 19.2% of patients in whom the leg was immobilised with a splint or not immobilised at all. The median duration of immobilisation was 3 weeks, with no significant differences between groups. The median time elapsed prior to weight bearing on the leg was 3 weeks, with a range of 1.5–6 weeks (IQR, 2–4). Follow-up X-rays were performed in 35% of cases at a median of 21 days post fracture (IQR, 19–27). Consolidation of the fracture could be seen in the X-rays in all patients but 1 (1.9%), a patient managed with a rigid cast in whom the X-ray revealed fracture displacement.

Comparison of patients with confirmed versus unconfirmed fracture.

| Unconfirmed fracture | Confirmed fracture | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of immobilisation, n (%) | .015a | |||

| Rigid | 2 (40%) | 40 (85.1%) | 42 (80.8%) | |

| Not rigid | 3 (60%) | 7 (14.9%) | 10 (19.2%) | |

| Duration of immobilisation (weeks) | 2 (2–2%) | 3 (2–4%) | 3 (2–4%) | .7b |

Comparison of patients with unconfirmed fracture and patients with radiologically confirmed fracture in terms of the type of immobilisation, expressed as the percentage distribution, and the duration of immobilisation in weeks, expressed as median (IQR).

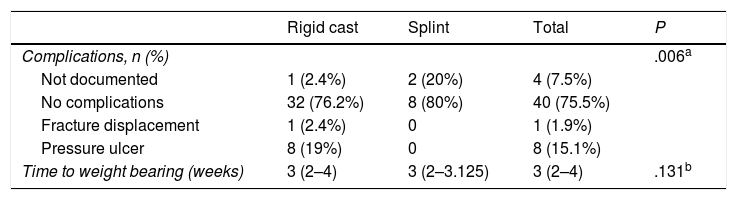

Complications developed in 21.4% of patients with rigid immobilisation, the most frequent being pressure ulcer (19% of patients with immobilisation), followed by fracture displacement (2.4%). There were no complications in patients that were not subject to immobilisation, although this particular outcome was not documented in 2 (20%) of the patients in this group that were lost to follow-up. When we compared patients managed with rigid casts versus splints, we found that complications were more frequent in the rigid immobilisation group (21.4% vs 0%; P=.006), with no significant differences between groups in the time elapsed to weight bearing (Table 5).

Outcomes of patients managed with immobilisation.

| Rigid cast | Splint | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications, n (%) | .006a | |||

| Not documented | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (20%) | 4 (7.5%) | |

| No complications | 32 (76.2%) | 8 (80%) | 40 (75.5%) | |

| Fracture displacement | 1 (2.4%) | 0 | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Pressure ulcer | 8 (19%) | 0 | 8 (15.1%) | |

| Time to weight bearing (weeks) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–3.125) | 3 (2–4) | .131b |

Outcomes in patients managed with a circumferential cast versus patients with a splint or not managed with immobilisation in terms of the incidence of complications and the median (IQR) time to weight bearing.

Classic notions regarding the presentation and approach to the evaluation and treatment of toddler's fracture differ from current practice, as demonstrated by the findings of our study. The classic diagnostic approach applying the Dunbar criteria1 and plain radiography as the sole method of confirmation are not currently the norm, and rigid immobilisation is no longer the only treatment option, as outcomes are not inferior with the use of flexible immobilisation or even without immobilisation.

Given the age at which this problem usually occurs and the intrinsic difficulty in examining these young patients, the application of the clinical criteria proposed by Dunbar1 (acute onset, inability to bear weight, tenderness on palpation of the bone, warmth in the tibial region and pain on ankle dorsiflexion) is not always possible. Excluding the acute onset, we found that a large proportion of patients only met 1 or 2 criteria in the physical examination, with suspicion of the diagnosis being left to the judgement of the medical provider, and the main variables assessed were acute onset, the mechanism of injury, avoidance of weight bearing and pain on palpation of the tibial region, compared to all other signs or symptoms.

The diagnostic test used most frequently continues to be the plain radiograph, which can not only confirm the diagnosis but also rule out other possible diseases. The characteristic X-ray pattern is a spiral fracture line in the distal third of the tibia (the segment involved most frequently), although this line may be difficult to detect or be absent in a significant percentage of cases (ranging from 13% to 60% in different case series).1–7 For this reason, some authors have been recently proposing the use of ultrasound as an alternative in cases that are not confirmed with plain radiography3,8 or even for the initial diagnostic evaluation, which would allow avoiding or reducing the adverse effects of exposure to ionising radiation.9,10 In our sample, the ultrasound scan was used for initial diagnosis in only 1 patient, and for subsequent evaluation in 5 patients due to the persistence of symptoms in the days that followed the initial evaluation, with results suggestive of fracture in 4 out of 5 (80%), 3 of who had had normal plain X-rays; in these cases, ultrasonography was essential to the diagnosis.

As for the management of toddler's fracture, several different strategies are used at present, and there is no consensus on which is the optimal approach.11 Traditionally, patients with confirmed fracture have been treated with a long-leg cast for 3–4 weeks, and those with suspected fracture with a similar approach until performance of the follow-up radiographic evaluation 10–14 days after.3–5 However, several recent studies show that these groups of patients are not managed in the same way in current clinical practice: patients with confirmed toddler's fracture are more likely to be treated with a circumferential cast compared to patients with unconfirmed fracture (92% vs 47% in the study by Sapru et al.,3 and 95% vs 14% in a nationwide study conducted in Canada11). In our study, 85% of patients with confirmed fracture were managed with a cast, compared to 40% of patients with unconfirmed fracture, a difference that was statistically significant (P=.015), which was consistent with the previous literature. In addition, in recent years several authors have analysed patient outcomes based on the type of immobilisation used (long-leg or short-leg circumferential cast, splint, bandaging or no immobilisation) and have not found significant differences in the incidence of fracture displacement or the time to weight bearing6,12,13; while lack of immobilisation with a cast or splint could prevent the skin breakdown observed in 17.3% of patients treated with this approach.12 Immobilisation with casts in paediatric patients is associated with skin changes in up to 27%, in addition to creating difficulties for the family in the management of everyday life, an increased number of visits to the emergency department due to problems with the cast11,12,14 and an increased need of follow-up care by medical specialists, which entails increases in health care costs and family expenditure.9 For these reasons, and since toddler's fracture is a stable fracture with a low incidence of complications, several authors11–13 have proposed conservative management without rigid immobilisation of patients coupled with adequate analgesia if the family agrees, which may not even require specialised follow-up.15 In our study, nearly 20% of patients were treated conservatively, and none experienced displacement, while we found no significant differences in the time to weight bearing based on the treatment approach; on the contrary, as described by other authors,12,13 we found that the use of casts was associated with an increase in morbidity, with 19% of patients developing pressure ulcers.

It is worth highlighting that while toddler's fracture is not one of the fractures that ought to trigger a strong suspicion of child abuse, and cases of physical abuse were not identified in our sample, previous studies have reported percentages of 7% to 11% of cases of this fracture resulting from abuse, especially those involving the middle and proximal thirds of the tibia.5,7,15,16 For this reason, physical abuse should always be contemplated in patients aged less than 3 years with long bone fractures, especially in cases in patients that do not yet walk, with family or social risk factors, where seeking care is delayed, with inconsistencies in the narrative or the physical examination, a history of previous fracture or atypical fracture, given the significant impact and deleterious consequences of such abuse in children.17,18

There are limitations to our study that we ought to discuss. The retrospective design limited the clinical data that were available for collection and analysis, for instance, in relation to the documentation of the application of Dunbar's diagnostic criteria,1 which depended on choices of the examining physician. On the other hand, the loss to follow-up of 2 patients in the no-immobilisation group resulted in an equal percentage of patients without complications documented in the health records.

In conclusion, despite the aforementioned limitations, it is reasonable to state that patients with toddler's fracture managed without a rigid cast had the same outcomes as patients managed with a cast, with no complications in the former group and a lesser treatment-related morbidity, as avoidance of casts can prevent the development of pressure ulcers. When it came to the use of diagnostic tests, we observed that plain radiography had a low sensitivity for the diagnosis of toddler's fracture and that the use of ultrasound in several cases in the group of patients with suspected fracture and normal radiographic findings contributed to the final diagnosis and prevented additional exposure to radiation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Llorente Pelayo S, Rodríguez Fernández J, Leonardo Cabello MT, Rubio Lorenzo M, García Alfaro MD, Arbona Jiménez C. Manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico actual de la fractura de los primeros pasos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;92:262–7.

Previous presentation: this study was presented at the XXIV Meeting of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría, May 9–11, 2019, Murcia, Spain.