Refractory Kawasaki disease (rKD) is defined as persistence of fever (≥38 °C) more than 36 h after completing the first intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusion at the standard dose (2 g/kg over 10−12 h).1 Interleukin-1 (IL-1) plays a crucial role in vascular inflammation and severe cardiac complications in Kawasaki disease (KD), especially in refractory cases.2 During the acute phase, IL-1β elevation and the expression of single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with its signaling pathway (ITPKC, ORAI1 and SLC8A1) may persist after IVIG, maintaining the inflammatory state and increasing the risk of coronary aneurysms, ventricular dysfunction and arrhythmia.2 At present, there is no consensus regarding the optimal management of rKD (10%–20%). Options such as a second IVIG dose, steroid therapy or infliximab have been found to chiefly help lower fever and reduce the length of stay, without a clear impact on coronary aneurysms.1 In this context, IL-1 blockade with anakinra has emerged as a promising alternative.

In this paper, we present three clinical cases of rKD treated with anakinra in our hospital since 2015 (6% of total cases). All patients had received first- and second-line treatment, including two doses of IVIG and steroid therapy, and, in one case, infliximab. The indication for anakinra was persistent fever, systemic inflammation or progression of coronary aneurysms, in contexts of varying severity, including cardiogenic shock in one patient.

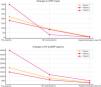

In all three cases, anakinra was delivered subcutaneously starting at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day that was escalated to 4 mg/kg/day in one patient. Patients exhibited a rapid clinical response, with resolution of fever in less than 24 h in all patients and progressive improvement of inflammatory markers. We observed partial or complete regression of coronary aneurysms in the weeks that followed. The median duration of treatment with anakinra was 33 days (range, 15–55 days), which was maintained until there was evidence of resolution of the inflammatory process and absence of severe coronary complications. Patient 3, who developed cardiogenic shock, required mechanical ventilation and inotropes (milrinone + noradrenaline) prior to initiation of anakinra. Table 1 and Fig. 1 present the clinical characteristics, previous treatment, changes in laboratory and echocardiographic findings and long-term follow-up of the patients.

Clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes of patients with refractory Kawasaki disease treated with anakinra.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age/sex/weight | 15 months/male/12 kg | 22 months/female/15 kg | 8 years/male/24 kg |

| Diagnostic and days elapsed from onset prior to first-line treatment | Complete KD after 5 days of fever | Complete KD after 6 days of fever | Complete KD after 7 days of fever + cardiogenic/vasoplegic shock |

| Treatment before anakinra | 2 doses IVIG + MP + ASA | 2 doses IVIG + MP + infliximab + ASA | 2 doses IVIG + MP + ASA + invasive MV + inotropes (milrinone + norepinephrine) |

| Clinical condition pre-anakinra | Persistent fever on day 11; LVEF of 62% | Persistent fever on day 12; LVEF of 68% | Persistent fever and shock on day 10; LVEF of 42% |

| Maximum dose of anakinra | 4 mg/kg/day SC | 2 mg/kg/day SC | 2 mg/kg/day SC |

| Resolution of fever | 12 h after escalation of anakinra dose | 24 h after initiation of anakinra | 24 h after initiation of anakinra |

| Length of stay | 23 days | 15 days | 19 days |

| Treatment after discharge | Anakinra + ASA | Anakinra + ASA | Anakinra + ACE-I + BB + ASA + |

| Total days of anakinra | 33 days (21 days at home) | 15 days (12 days at home) | 55 days (46 days at home) |

| Criteria for discontinuing anakinra | Absence of fever, normal APRs and echocardiographic evidence of aneurysm regression | Absence of fever, normal APRs and echocardiographic findings | Absence of fever, normal APRs and coronary CT findings |

| Most recent follow-up | At 3 years: LAD ectasia (Z-score 2.3). Treatment with ASA | At 2.5 years: no coronary abnormalities or treatment | At 4 years: no coronary abnormalities or treatment |

Abbreviations: ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; APR, acute phase reactant; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; BB, beta-blocker; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; KD, Kawasaki disease; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MP, methylprednisolone; MVmechanical ventilation; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; SC, subcutaneous.

Coronary z score calculated using the Detroit 2008 data as reference.

C-reactive protein, NT-proBNP, maximum coronary z score of the left anterior descending artery (Detroit method) and LVEF in the three patients before treatment, at 48 h post-anakinra and at hospital discharge.

CRP, C-reactive protein; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide.

These cases were consistent with the recent evidence on the efficacy and safety of anakinra for treatment of rKD. Preclinical studies in murine models (LCCWE) already showed that anakinra could control inflammation and prevent the complications associated with KD.1 In humans, a systematic review conducted by Ferrara et al. that included 22 clinical cases highlighted its efficacy in critical situations such as macrophage activation syndrome, cardiogenic shock and giant aneurysms.3 In the KAWAKINRA open-label trial (phase IIa), which evaluated 16 patients with rKD treated for 14 days with anakinra dose escalation (2−6 mg/kg/día), anakinra achieved resolution of fever in 75% of patients and a significant decrease in inflammatory markers with a reduction in C-reactive protein levels greater than 20% compared to baseline within 48 h of administering the last adjusted dose of anakinra, while nearly half of patients exhibited partial or complete normalization of coronary dilatation (coronary z score) on day 45, with no documented cases of severe infection or death following use of anakinra.4 On the other hand, the ANAKID trial (phase I/IIa) included 22 pediatric patients with rKD complicated by coronary aneurysms treated with anakinra (2−11 mg/kg/day) for 6 weeks. The results showed adequate tolerability and a significant reduction in inflammatory markers (IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α), in addition to a slight decrease in coronary z scores5 by the end of treatment. The findings of this trial also suggested that intravenous administration is preferable during hospitalization in the acute phase to maintain consistent serum drug levels, while the subcutaneous route is more appropriate for prolonged outpatient treatment until the inflammation resolves fully.6 While the results are promising, there is still uncertainty due to the small sample sizes and the absence of control groups in these initial studies. Clinical trials such as ANACOMP (phase III; n = 84) aim at providing robust evidence of its efficacy compared to a second dose of IGIV.7

Our experience indicates that blocking IL-1 with anakinra is a therapeutic option worth considering in rKD. Its ability to quickly and safely control systemic inflammation and prevent serious cardiovascular complications makes it a valuable alternative in critical situations such as cardiogenic shock or giant aneurysms. A key advantage of anakinra is the flexibility in its administration, avoiding the fluid overload resulting from a second dose of IVIG; although patient 3 received a second dose in adherence to current consensus recommendations,1 it was still necessary to resort to anakinra later on to achieve adequate clinical and inflammation control. This suggests that early use of anakinra may be considered in the future, especially in patients requiring fluid restriction, for instance, in the context of severe ventricular dysfunction. In addition, its half-life allows rapid adjustments based on the clinical response. The clinical trials currently underway will be key in establishing its place in the therapeutic algorithm and identifying the patient subgroups that could benefit most significantly from the treatment.