Edited by: Paz González Rodríguez

Madrid Health Service. Primary Care Paediatrics. Madrid . Spain

María Aparicio Rodrigo

Madrid Health Service. Primary Care Paediatrics. Complutense University of Madrid. Madrid . Spain

Last update: September 2025

More infoEvidence-based medicine seeks the rigorous application of the best available scientific evidence to clinical decision-making. However, when the evidence is insufficient or inconsistent, consensus documents can guide clinical practice and reduce variability of care. These documents, developed by experts, require a structured approach to ensure their validity and applicability. A consensus document is a report produced by experts following a formalized process to answer a specific clinical question. The methodology used must be rigorous to minimize biases, such as dominance of certain experts or the panel not being representative. The most widely used formal consensus methods are the Delphi technique, the nominal group technique, the RAND/UCLA method, consensus conferences and other, less structured methods such as consensus meetings and focus groups. To ensure the quality of a consensus document, the use of standards such as the ACCORD guideline is essential. This guideline provides drafting criteria, ensuring the inclusion of detailed information regarding the materials, resources (both human and financial) and procedures used during the consensus process. The critical reading of these documents should take into account factors such as the representativeness of the panel, the clarity of the consensus criteria and potential conflicts of interest. In this sense, critical appraisal tools, such as those proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute, facilitate the identification of biases and the evaluation of the validity of recommendations.

La Medicina Basada en la Evidencia busca la aplicación rigurosa de la mejor evidencia científica para la toma de decisiones clínicas. Sin embargo, cuando la evidencia es insuficiente o inconsistente, los documentos de consenso permiten guiar la práctica clínica y reducir la variabilidad en la atención sanitaria. Estos documentos, elaborados por expertos, requieren un enfoque estructurado para garantizar su validez y aplicabilidad. Un documento de consenso es un informe elaborado por expertos que sigue un proceso formalizado para responder a una pregunta clínica específica. La metodología utilizada debe ser rigurosa para minimizar sesgos, como la influencia de expertos dominantes o la falta de representatividad del panel consultado. Los métodos formales de consenso más utilizados son: la técnica Delphi, el Grupo Nominal, el método RAND/UCLA, las Conferencias de Consenso y otros menos estructurados como las Reuniones de Consenso y los Grupos focales. Para garantizar la calidad de un documento de consenso, es fundamental la utilización de estándares como la guía ACCORD. Esta guía proporciona criterios para su redacción, asegurando la inclusión de información detallada sobre los materiales, recursos (tanto humanos como financieros) y procedimientos utilizados durante el proceso de consenso. La lectura crítica de estos documentos debe considerar factores como la representatividad del panel, la claridad de los criterios de consenso y la existencia de posibles conflictos de interés. En este sentido, herramientas de evaluación crítica, como las propuestas por el Instituto Joanna Briggs, facilitan la identificación de sesgos y la evaluación de la validez de las recomendaciones.

Evidence-based medicine refers to the application of the best available evidence in making decisions about the care of patients.1 However, in some instances, the current evidence is insufficient or of poor quality. In these cases, the expert consensus becomes a useful tool to offer unified answers and reduce variability in clinical practice.

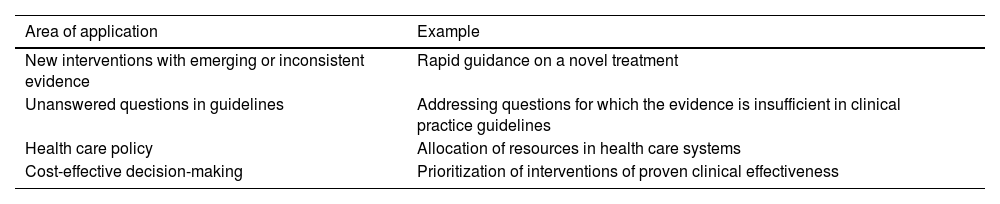

A consensus document is a report developed by a group of experts in a rigorous process that involves the application of a formal and standardized consensus method to answer a clinical question.2 Informal consensus exercises may be carried out sometimes, but they are more likely to have drawbacks, such as the potential for particular individuals to dominate the discussion and decision-making, the influence of external pressures or extreme decisions being made by experts with very strong opinions. Table 1 presents scenarios in in which expert consensus may be used in the health care field.

Applications of consensus exercises in health care-related activities or research.

| Area of application | Example |

|---|---|

| New interventions with emerging or inconsistent evidence | Rapid guidance on a novel treatment |

| Unanswered questions in guidelines | Addressing questions for which the evidence is insufficient in clinical practice guidelines |

| Health care policy | Allocation of resources in health care systems |

| Cost-effective decision-making | Prioritization of interventions of proven clinical effectiveness |

The development of a consensus document involves the selection of a topic for which there is no current evidence or there is controversy requiring clarification (clinical question). An exhaustive review of the scientific literature should be carried out before starting the consensus exercise (there may be consensus based on evidence or not based on it, if there is none, but the literature must be reviewed nonetheless), followed by the definition of the consensus development method to be implemented and the formation of a group of experts. Lastly, the group must write the conclusions/recommendations and draft the document for publication, ensuring transparency and rigor.3–6

There are certain limitations to the expert consensus process. It may just reflect what is known as “collective ignorance”, that is, yield agreements that, while representative of the group’s views, lack a solid scientific basis. In addition, it is not always possible to solve deep disagreements, especially when the experts hold different opinions. In consequence, expert consensus should be considered a complement to the best available evidence, and never a substitute for it.7

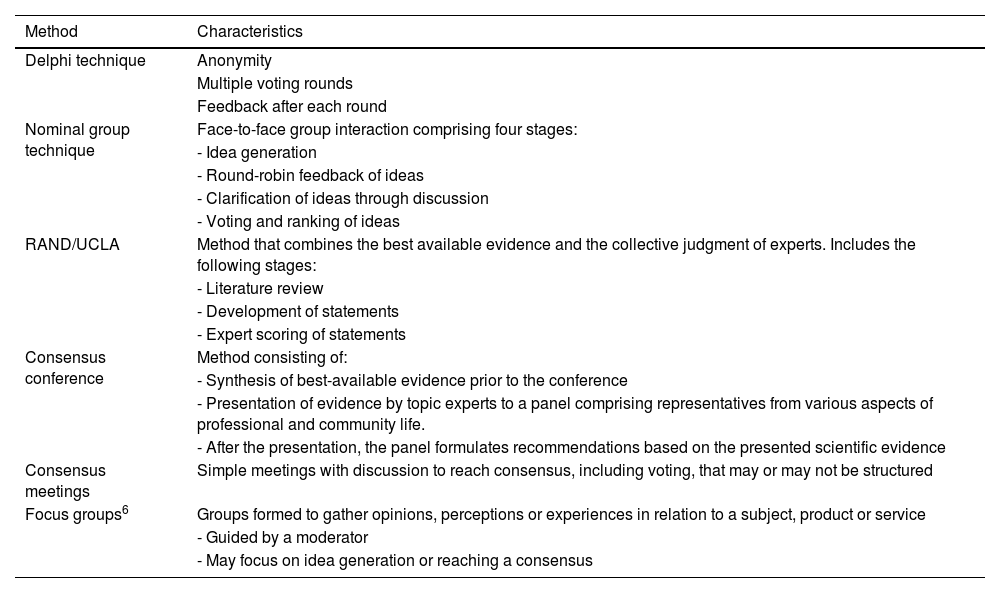

Formal consensus development methodsThe most commonly used methods for social- and health-related topics are the Delphi technique, the nominal group technique, the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method, the consensus development conference, consensus meetings and focus groups (Table 2). The choice of method depends on the type of question, the available time and technical limitations or feasibility.

Common consensus methods used in health care-related activities or research.

| Method | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Delphi technique | Anonymity |

| Multiple voting rounds | |

| Feedback after each round | |

| Nominal group technique | Face-to-face group interaction comprising four stages: |

| - Idea generation | |

| - Round-robin feedback of ideas | |

| - Clarification of ideas through discussion | |

| - Voting and ranking of ideas | |

| RAND/UCLA | Method that combines the best available evidence and the collective judgment of experts. Includes the following stages: |

| - Literature review | |

| - Development of statements | |

| - Expert scoring of statements | |

| Consensus conference | Method consisting of: |

| - Synthesis of best-available evidence prior to the conference | |

| - Presentation of evidence by topic experts to a panel comprising representatives from various aspects of professional and community life. | |

| - After the presentation, the panel formulates recommendations based on the presented scientific evidence | |

| Consensus meetings | Simple meetings with discussion to reach consensus, including voting, that may or may not be structured |

| Focus groups6 | Groups formed to gather opinions, perceptions or experiences in relation to a subject, product or service |

| - Guided by a moderator | |

| - May focus on idea generation or reaching a consensus |

Adapted from Logullo et al.6

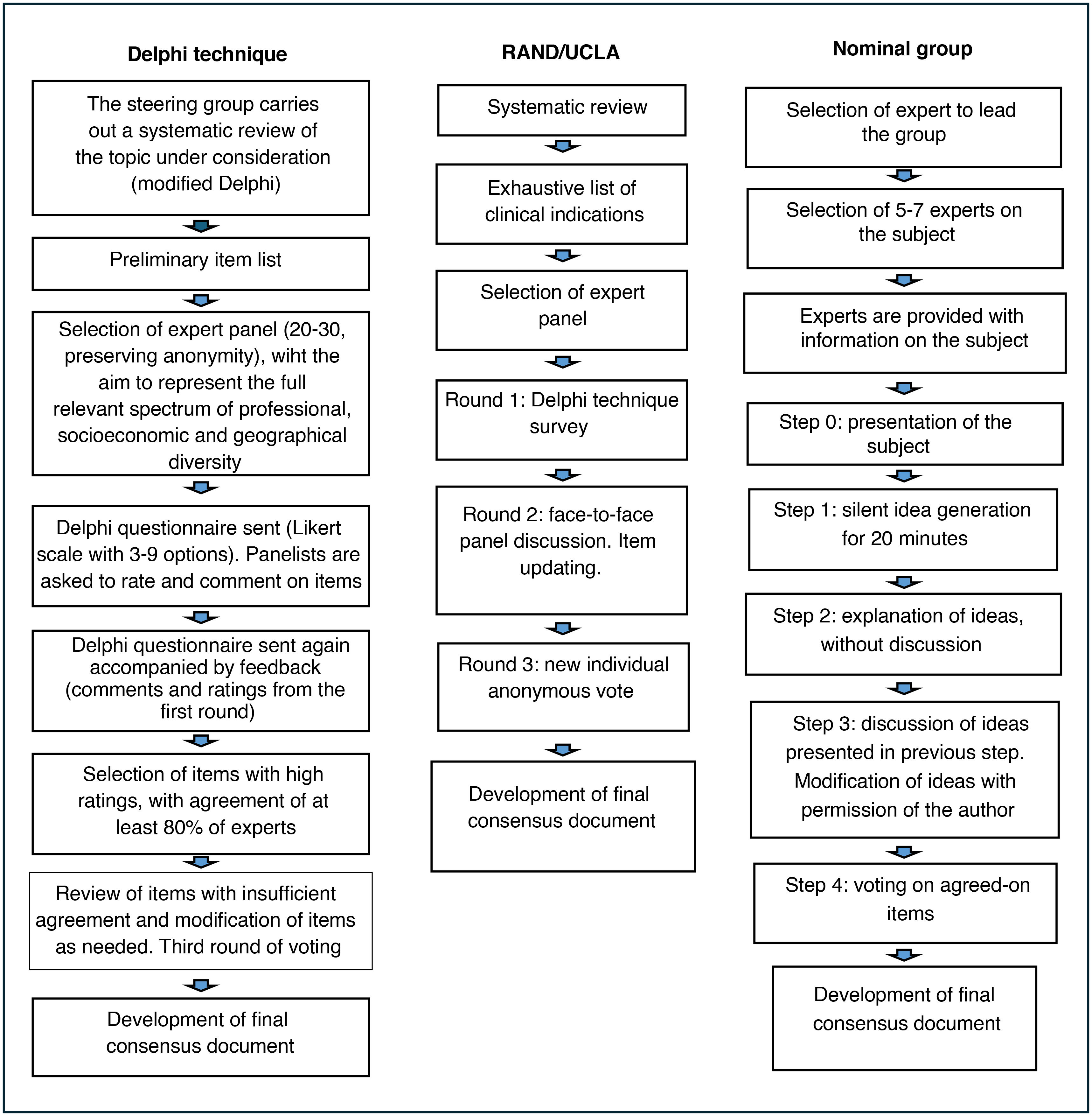

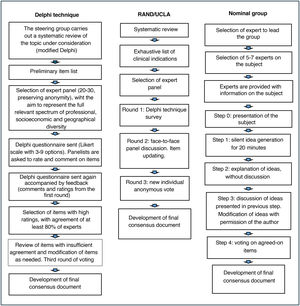

The Delphi method4,8 is the most structured and most widely used approach. The main drawback is that it requires more time. Questionnaires are sent through mail/email (anonymity), and it is possible to engage a greater number of participants without geographical barriers, but this also increases the probability of losing participants before completion9 (Fig. 1) and precludes the direct interaction of participants during the consensus process. A steering group selects a panel of experts (preserving anonymity), striving to represent the full spectrum of professional, socioeconomic and geographical diversity. There is no agreement regarding the most suitable number of experts, but in most cases between 20–30 participants are involved in this technique. The expert panel does not include the steering group members. The steering group may carry out a systematic review on the topic before the consensus development process, crafting a preliminary list of questions (modified Delphi),8 or simply survey the opinions of experts through one or more open-ended questions on the topic (traditional Delphi). The results of this phase are converted into a list of statements/items in a questionnaire. The questionnaire is submitted to the experts, who have to rate their agreement with the items and provide further feedback through comments or open-ended questions. Agreement is rated on a Likert scale, usually with 3–9 answer choices. The same questionnaire is sent in the second round, this time including feedback on the answers of participants and the most relevant comments from the previous round. Items with the highest agreement (at least 80% of participants) in both rounds are selected. Items with insufficient agreement or for which the threshold was only reached in one round are reviewed and modified as needed. A third round is then carried out. After this vote, the steering group meets and produces the definitive document. Given the characteristics of the method, the agreement or consensus is considered inferior to the consensus achieved through the nominal group technique.

The nominal group technique, which, like the Delphi technique, is one of the most widely used structured consensus development methods, allows more interaction between experts on the topic through face-to-face or online meetings, with real-time feedback and a shorter overall duration4,10,11 (Fig. 1). Participation of 5–7 experts is recommended. The process starts with the selection of the professional with the greatest expertise on the topic, who is then responsible for the selection of the rest of the group. The facilitator provides information on the topic to be discussed to participants before they meet. The process comprises four stages: the first one involves individual reflection for 20 min. In the second, participants share their ideas one by one, taking turns, and without any discussion until all participants had provided their feedback (round robin). In the third stage, participants discuss the ideas shared in the previous stage, and the facilitator ensures that all panelists participate in the discussion of all the ideas. The initial ideas are then modified with the consent of the participants that had proposed them originally. In the fourth and last stage, the group votes on the proposed items as modified in the previous stage until a consensus is reached.

The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method4,12 is a hybrid of the two previous methods (Fig. 1). In this approach, the structure of meetings is customized based on the participants and the topic under discussion. The panel typically has 7–15 members. The process starts with a systematic review of the literature by the coordinating committee to establish a rigorous foundation for the discussion. A list of clinical indications is developed based on this evidence, ensuring that the list is comprehensive and the indications are mutually exclusive and applicable to clinical practice. The next step is the selection of an expert panel composed of specialists in different fields related to the topic at hand. The evaluation process is structured in three rounds. First round: Delphi technique questionnaire with individual and anonymous rating of the included items on a Likert scale. Second round: face-to-face meeting of the panel to discuss disagreements and re-rate the appropriateness of items to improve consensus. Third round: updating of items based on the preceding discussion and new round of anonymous voting with rating on a Likert scale. After the voting, each item is categorized as appropriate, inappropriate or uncertain, based on the group median rating. One of the advantages of this method is that it implements a more sophisticated analysis, using interpercentile ranges (raw or adjusted), palliating the drawbacks intrinsic to the variation in the number of experts and the effect of disagreements. There are multiple variants of this method.

The consensus development conference4 approach involves face-to-face meetings of a multidisciplinary group of experts. A steering committee selects a panel of approximately 10 experts. The process is more flexible compared to the previous methods. It starts with the formulation of questions regarding the topic of interest and the performance of a systematic review by a small group of experts that is not involved in the decision-making process. This group of experts present the results to the members of the panel and answer their questions. Subsequently, the panel members meet to deliberate on the issue under the direction of one of them, appointed to act as the chairperson, to reach consensus. This technique has the advantage of fostering dialogue and debate, but it also has significant drawbacks in terms of its cost and time constraints.

Consensus meetings6 and focus groups are less structured options. They consist in a meeting of experts to discuss specific topics in an organized manner in order to reach a consensus. They are based on discussion, negotiation and, sometimes, voting. During these sessions, the agreed-on recommendations and the arguments against certain points get documented. Their structured varies depending on the topic under consideration and the composition of the group.

ACCORD: accurate consensus reporting guidelineIn 1996, the CONSORT statement was published with the aim of improving quality in reporting randomized controlled trials. Since then, a growing number of reporting guidelines have been published for other methodological designs, many of which are available at the EQUATOR website.13 However, despite the importance of consensus-based guidance in many key health care decisions, a reporting guideline has not been available for consensus development exercises until 2024.

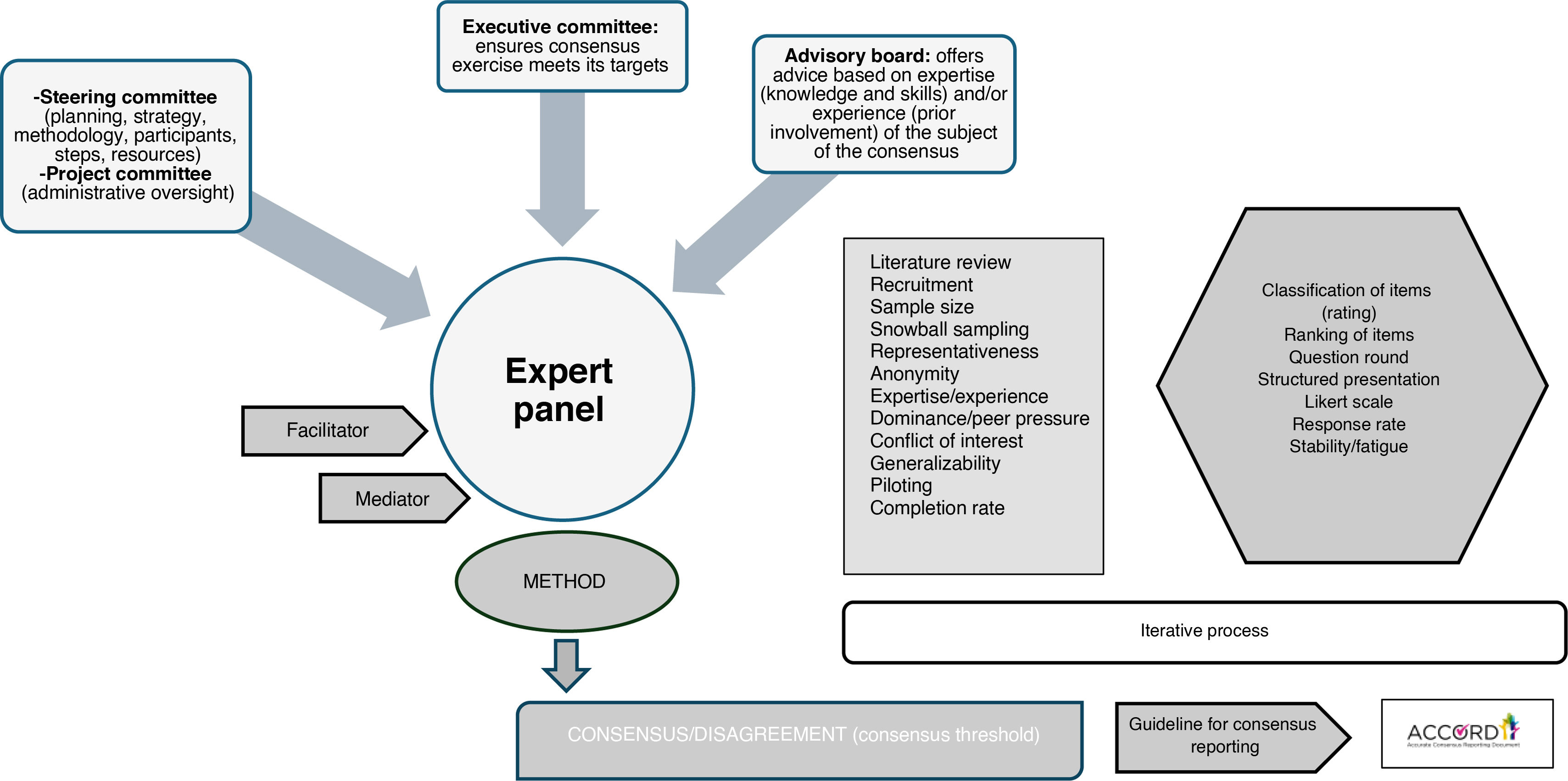

Per its authors, the ACcurate COnsensus Reporting Document (ACCORD) is a guideline developed to help report any consensus methods used in biomedical research, regardless of the health field, techniques used, or application2 (Fig. 2). As is the case of all other reporting guidelines, the purpose of the ACCORD guideline is to help researchers to be transparent in their reports, including detailed information about the materials, resources (both human and financial), and procedures used in their investigations. This way, readers, having access to all the necessary information, can judge the trustworthiness and applicability of their results/recommendations of the consensus document.

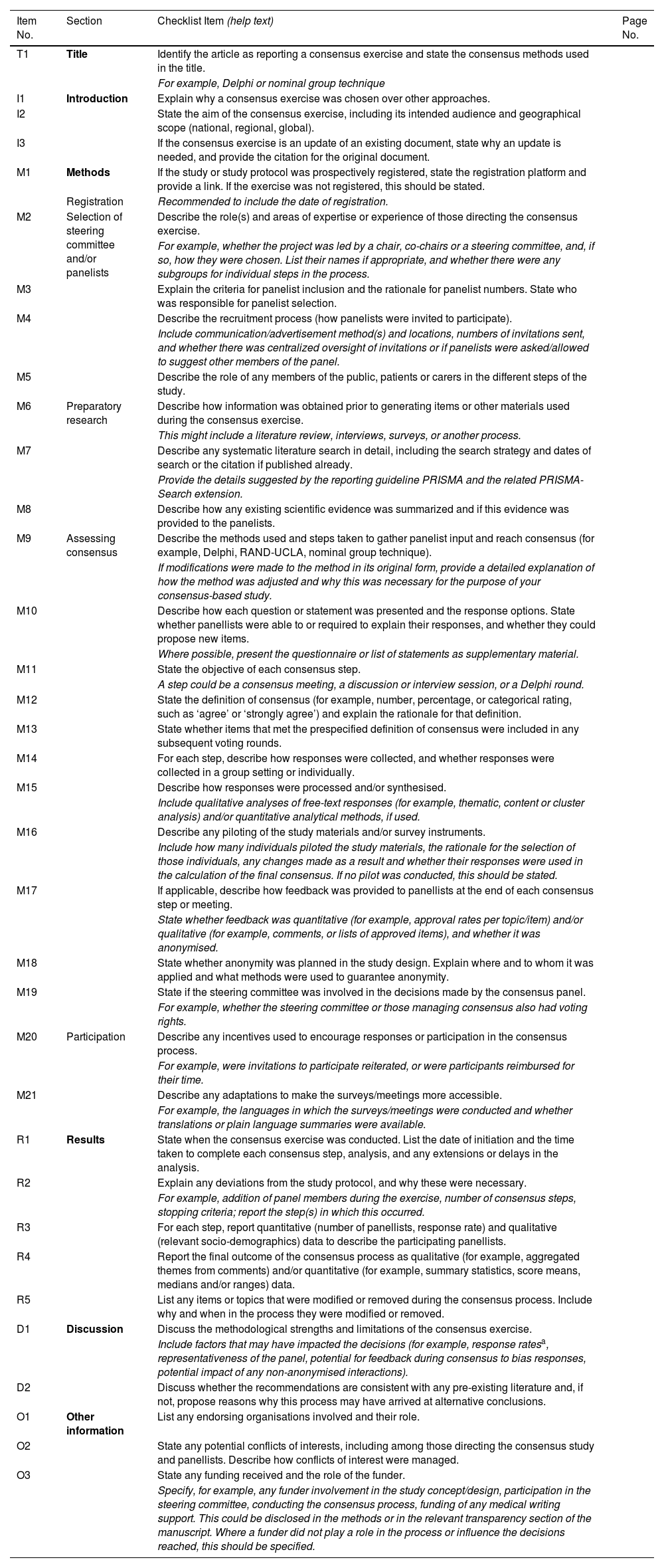

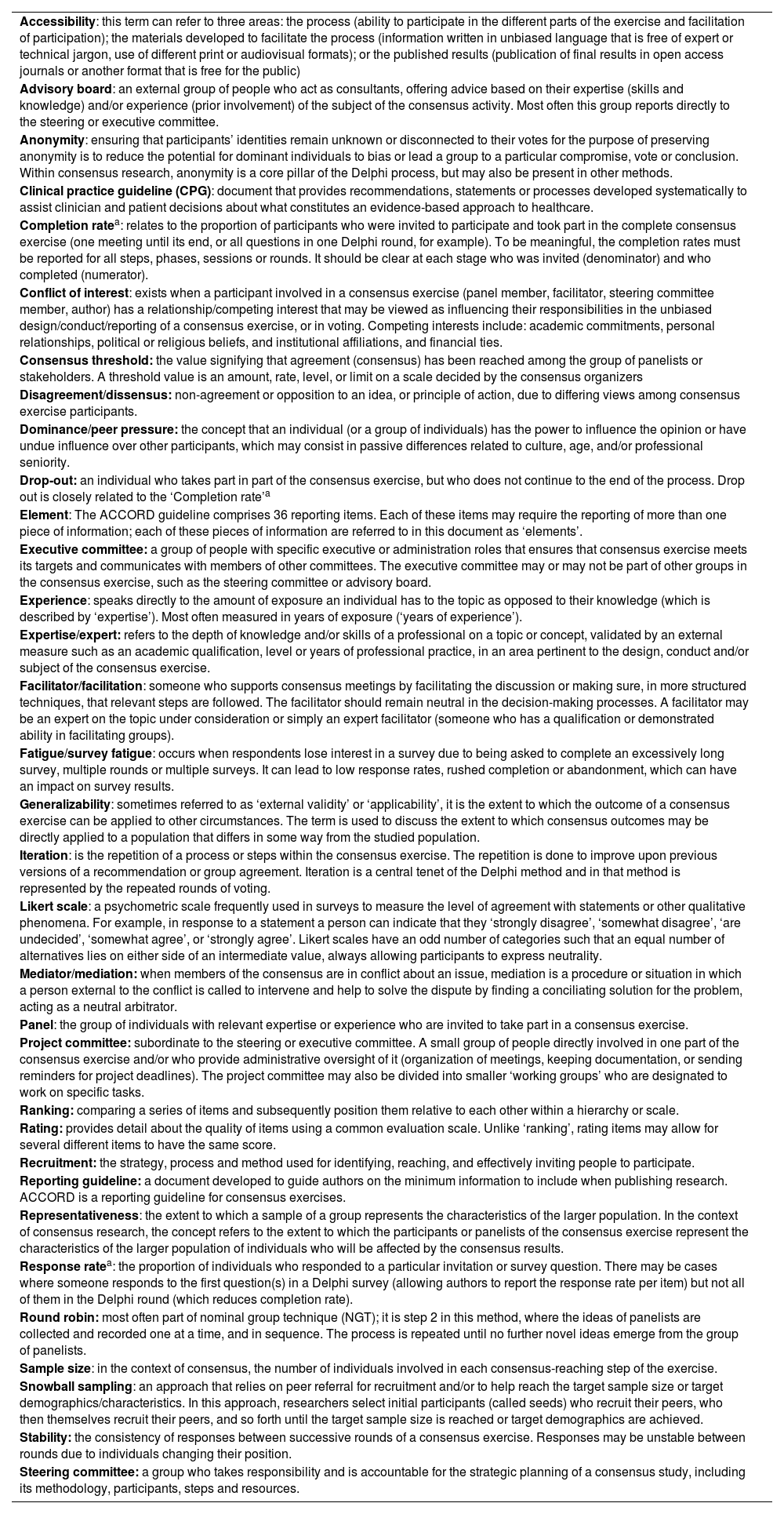

We proceed to summarize the contents of this guideline. More detailed information, including examples and the original checklist, can be found in the published documentation available at EQUATOR and the ACCORD website.6 There are also free-access versions in Spanish of the checklist and an abridged glossary of terms (Tables 3 and 4).

ACCORD checklist.

| Item No. | Section | Checklist Item (help text) | Page No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Title | Identify the article as reporting a consensus exercise and state the consensus methods used in the title. | |

| For example, Delphi or nominal group technique | |||

| I1 | Introduction | Explain why a consensus exercise was chosen over other approaches. | |

| I2 | State the aim of the consensus exercise, including its intended audience and geographical scope (national, regional, global). | ||

| I3 | If the consensus exercise is an update of an existing document, state why an update is needed, and provide the citation for the original document. | ||

| M1 | Methods | If the study or study protocol was prospectively registered, state the registration platform and provide a link. If the exercise was not registered, this should be stated. | |

| Registration | Recommended to include the date of registration. | ||

| M2 | Selection of steering committee and/or panelists | Describe the role(s) and areas of expertise or experience of those directing the consensus exercise. | |

| For example, whether the project was led by a chair, co-chairs or a steering committee, and, if so, how they were chosen. List their names if appropriate, and whether there were any subgroups for individual steps in the process. | |||

| M3 | Explain the criteria for panelist inclusion and the rationale for panelist numbers. State who was responsible for panelist selection. | ||

| M4 | Describe the recruitment process (how panelists were invited to participate). | ||

| Include communication/advertisement method(s) and locations, numbers of invitations sent, and whether there was centralized oversight of invitations or if panelists were asked/allowed to suggest other members of the panel. | |||

| M5 | Describe the role of any members of the public, patients or carers in the different steps of the study. | ||

| M6 | Preparatory research | Describe how information was obtained prior to generating items or other materials used during the consensus exercise. | |

| This might include a literature review, interviews, surveys, or another process. | |||

| M7 | Describe any systematic literature search in detail, including the search strategy and dates of search or the citation if published already. | ||

| Provide the details suggested by the reporting guideline PRISMA and the related PRISMA-Search extension. | |||

| M8 | Describe how any existing scientific evidence was summarized and if this evidence was provided to the panelists. | ||

| M9 | Assessing consensus | Describe the methods used and steps taken to gather panelist input and reach consensus (for example, Delphi, RAND-UCLA, nominal group technique). | |

| If modifications were made to the method in its original form, provide a detailed explanation of how the method was adjusted and why this was necessary for the purpose of your consensus-based study. | |||

| M10 | Describe how each question or statement was presented and the response options. State whether panellists were able to or required to explain their responses, and whether they could propose new items. | ||

| Where possible, present the questionnaire or list of statements as supplementary material. | |||

| M11 | State the objective of each consensus step. | ||

| A step could be a consensus meeting, a discussion or interview session, or a Delphi round. | |||

| M12 | State the definition of consensus (for example, number, percentage, or categorical rating, such as ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’) and explain the rationale for that definition. | ||

| M13 | State whether items that met the prespecified definition of consensus were included in any subsequent voting rounds. | ||

| M14 | For each step, describe how responses were collected, and whether responses were collected in a group setting or individually. | ||

| M15 | Describe how responses were processed and/or synthesised. | ||

| Include qualitative analyses of free-text responses (for example, thematic, content or cluster analysis) and/or quantitative analytical methods, if used. | |||

| M16 | Describe any piloting of the study materials and/or survey instruments. | ||

| Include how many individuals piloted the study materials, the rationale for the selection of those individuals, any changes made as a result and whether their responses were used in the calculation of the final consensus. If no pilot was conducted, this should be stated. | |||

| M17 | If applicable, describe how feedback was provided to panellists at the end of each consensus step or meeting. | ||

| State whether feedback was quantitative (for example, approval rates per topic/item) and/or qualitative (for example, comments, or lists of approved items), and whether it was anonymised. | |||

| M18 | State whether anonymity was planned in the study design. Explain where and to whom it was applied and what methods were used to guarantee anonymity. | ||

| M19 | State if the steering committee was involved in the decisions made by the consensus panel. | ||

| For example, whether the steering committee or those managing consensus also had voting rights. | |||

| M20 | Participation | Describe any incentives used to encourage responses or participation in the consensus process. | |

| For example, were invitations to participate reiterated, or were participants reimbursed for their time. | |||

| M21 | Describe any adaptations to make the surveys/meetings more accessible. | ||

| For example, the languages in which the surveys/meetings were conducted and whether translations or plain language summaries were available. | |||

| R1 | Results | State when the consensus exercise was conducted. List the date of initiation and the time taken to complete each consensus step, analysis, and any extensions or delays in the analysis. | |

| R2 | Explain any deviations from the study protocol, and why these were necessary. | ||

| For example, addition of panel members during the exercise, number of consensus steps, stopping criteria; report the step(s) in which this occurred. | |||

| R3 | For each step, report quantitative (number of panellists, response rate) and qualitative (relevant socio-demographics) data to describe the participating panellists. | ||

| R4 | Report the final outcome of the consensus process as qualitative (for example, aggregated themes from comments) and/or quantitative (for example, summary statistics, score means, medians and/or ranges) data. | ||

| R5 | List any items or topics that were modified or removed during the consensus process. Include why and when in the process they were modified or removed. | ||

| D1 | Discussion | Discuss the methodological strengths and limitations of the consensus exercise. | |

| Include factors that may have impacted the decisions (for example, response ratesa, representativeness of the panel, potential for feedback during consensus to bias responses, potential impact of any non-anonymised interactions). | |||

| D2 | Discuss whether the recommendations are consistent with any pre-existing literature and, if not, propose reasons why this process may have arrived at alternative conclusions. | ||

| O1 | Other information | List any endorsing organisations involved and their role. | |

| O2 | State any potential conflicts of interests, including among those directing the consensus study and panellists. Describe how conflicts of interest were managed. | ||

| O3 | State any funding received and the role of the funder. | ||

| Specify, for example, any funder involvement in the study concept/design, participation in the steering committee, conducting the consensus process, funding of any medical writing support. This could be disclosed in the methods or in the relevant transparency section of the manuscript. Where a funder did not play a role in the process or influence the decisions reached, this should be specified. |

Source: Gattrell et al.2 This table has been adapted (with Spanish and English versions) by members of the Committee/Working Group on Evidence-Based Pediatrics of the AEP and AEPap. This table is licensed under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 license. https://www.aeped.es/comite-pediatria-basada-en-evidencia/documentos/lista-verificacion-accord.

Summary of the glossary of terms defined in the context of the ACCORD guideline.

| Accessibility: this term can refer to three areas: the process (ability to participate in the different parts of the exercise and facilitation of participation); the materials developed to facilitate the process (information written in unbiased language that is free of expert or technical jargon, use of different print or audiovisual formats); or the published results (publication of final results in open access journals or another format that is free for the public) |

| Advisory board: an external group of people who act as consultants, offering advice based on their expertise (skills and knowledge) and/or experience (prior involvement) of the subject of the consensus activity. Most often this group reports directly to the steering or executive committee. |

| Anonymity: ensuring that participants’ identities remain unknown or disconnected to their votes for the purpose of preserving anonymity is to reduce the potential for dominant individuals to bias or lead a group to a particular compromise, vote or conclusion. Within consensus research, anonymity is a core pillar of the Delphi process, but may also be present in other methods. |

| Clinical practice guideline (CPG): document that provides recommendations, statements or processes developed systematically to assist clinician and patient decisions about what constitutes an evidence-based approach to healthcare. |

| Completion ratea: relates to the proportion of participants who were invited to participate and took part in the complete consensus exercise (one meeting until its end, or all questions in one Delphi round, for example). To be meaningful, the completion rates must be reported for all steps, phases, sessions or rounds. It should be clear at each stage who was invited (denominator) and who completed (numerator). |

| Conflict of interest: exists when a participant involved in a consensus exercise (panel member, facilitator, steering committee member, author) has a relationship/competing interest that may be viewed as influencing their responsibilities in the unbiased design/conduct/reporting of a consensus exercise, or in voting. Competing interests include: academic commitments, personal relationships, political or religious beliefs, and institutional affiliations, and financial ties. |

| Consensus threshold: the value signifying that agreement (consensus) has been reached among the group of panelists or stakeholders. A threshold value is an amount, rate, level, or limit on a scale decided by the consensus organizers |

| Disagreement/dissensus: non-agreement or opposition to an idea, or principle of action, due to differing views among consensus exercise participants. |

| Dominance/peer pressure: the concept that an individual (or a group of individuals) has the power to influence the opinion or have undue influence over other participants, which may consist in passive differences related to culture, age, and/or professional seniority. |

| Drop-out: an individual who takes part in part of the consensus exercise, but who does not continue to the end of the process. Drop out is closely related to the ‘Completion rate’a |

| Element: The ACCORD guideline comprises 36 reporting items. Each of these items may require the reporting of more than one piece of information; each of these pieces of information are referred to in this document as ‘elements’. |

| Executive committee: a group of people with specific executive or administration roles that ensures that consensus exercise meets its targets and communicates with members of other committees. The executive committee may or may not be part of other groups in the consensus exercise, such as the steering committee or advisory board. |

| Experience: speaks directly to the amount of exposure an individual has to the topic as opposed to their knowledge (which is described by ‘expertise’). Most often measured in years of exposure (‘years of experience’). |

| Expertise/expert: refers to the depth of knowledge and/or skills of a professional on a topic or concept, validated by an external measure such as an academic qualification, level or years of professional practice, in an area pertinent to the design, conduct and/or subject of the consensus exercise. |

| Facilitator/facilitation: someone who supports consensus meetings by facilitating the discussion or making sure, in more structured techniques, that relevant steps are followed. The facilitator should remain neutral in the decision-making processes. A facilitator may be an expert on the topic under consideration or simply an expert facilitator (someone who has a qualification or demonstrated ability in facilitating groups). |

| Fatigue/survey fatigue: occurs when respondents lose interest in a survey due to being asked to complete an excessively long survey, multiple rounds or multiple surveys. It can lead to low response rates, rushed completion or abandonment, which can have an impact on survey results. |

| Generalizability: sometimes referred to as ‘external validity’ or ‘applicability’, it is the extent to which the outcome of a consensus exercise can be applied to other circumstances. The term is used to discuss the extent to which consensus outcomes may be directly applied to a population that differs in some way from the studied population. |

| Iteration: is the repetition of a process or steps within the consensus exercise. The repetition is done to improve upon previous versions of a recommendation or group agreement. Iteration is a central tenet of the Delphi method and in that method is represented by the repeated rounds of voting. |

| Likert scale: a psychometric scale frequently used in surveys to measure the level of agreement with statements or other qualitative phenomena. For example, in response to a statement a person can indicate that they ‘strongly disagree’, ‘somewhat disagree’, ‘are undecided’, ‘somewhat agree’, or ‘strongly agree’. Likert scales have an odd number of categories such that an equal number of alternatives lies on either side of an intermediate value, always allowing participants to express neutrality. |

| Mediator/mediation: when members of the consensus are in conflict about an issue, mediation is a procedure or situation in which a person external to the conflict is called to intervene and help to solve the dispute by finding a conciliating solution for the problem, acting as a neutral arbitrator. |

| Panel: the group of individuals with relevant expertise or experience who are invited to take part in a consensus exercise. |

| Project committee: subordinate to the steering or executive committee. A small group of people directly involved in one part of the consensus exercise and/or who provide administrative oversight of it (organization of meetings, keeping documentation, or sending reminders for project deadlines). The project committee may also be divided into smaller ‘working groups’ who are designated to work on specific tasks. |

| Ranking: comparing a series of items and subsequently position them relative to each other within a hierarchy or scale. |

| Rating: provides detail about the quality of items using a common evaluation scale. Unlike ‘ranking’, rating items may allow for several different items to have the same score. |

| Recruitment: the strategy, process and method used for identifying, reaching, and effectively inviting people to participate. |

| Reporting guideline: a document developed to guide authors on the minimum information to include when publishing research. ACCORD is a reporting guideline for consensus exercises. |

| Representativeness: the extent to which a sample of a group represents the characteristics of the larger population. In the context of consensus research, the concept refers to the extent to which the participants or panelists of the consensus exercise represent the characteristics of the larger population of individuals who will be affected by the consensus results. |

| Response ratea: the proportion of individuals who responded to a particular invitation or survey question. There may be cases where someone responds to the first question(s) in a Delphi survey (allowing authors to report the response rate per item) but not all of them in the Delphi round (which reduces completion rate). |

| Round robin: most often part of nominal group technique (NGT); it is step 2 in this method, where the ideas of panelists are collected and recorded one at a time, and in sequence. The process is repeated until no further novel ideas emerge from the group of panelists. |

| Sample size: in the context of consensus, the number of individuals involved in each consensus-reaching step of the exercise. |

| Snowball sampling: an approach that relies on peer referral for recruitment and/or to help reach the target sample size or target demographics/characteristics. In this approach, researchers select initial participants (called seeds) who recruit their peers, who then themselves recruit their peers, and so forth until the target sample size is reached or target demographics are achieved. |

| Stability: the consistency of responses between successive rounds of a consensus exercise. Responses may be unstable between rounds due to individuals changing their position. |

| Steering committee: a group who takes responsibility and is accountable for the strategic planning of a consensus study, including its methodology, participants, steps and resources. |

Source: Logullo et al.6 Adapted by members of the Committee/Working Group on Evidence-Based Pediatrics of the AEP and AEPap. This table is licensed under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 license. https://www.aeped.es/comite-pediatria-basada-en-evidencia/documentos/.

The title must identify the article as a consensus document as well as the consensus development method that was used so that readers can assess its robustness.

IntroductionThe introduction must provide information on three elements: the reason why a consensus exercise was chosen over other approaches, indicating evidence is currently absent, missing, or uncertain or a consensus exercise was considered necessary to provide clarity on a specific issue (I1), the specific aim of the consensus exercise (I2) and whether the consensus exercise is an update of an existing document (I3).

MethodsThe methods section encompasses 21 of the 35 items of ACCORD, which highlights its importance. The first recommendation for this section is to state whether the protocol of the consensus was registered (M1). This should be followed by a detailed description of the following:

- 1

The procedure for the selection of the steering committee, indicating the fields of expertise and experience of its members, and for the panelists that participated in the consensus exercise, in addition to the role of any members of the public, patients, or carers in the study (M2–M5).

- 2

The preliminary search for information, specifying how information was obtained prior to generating items or other materials for discussion, including the search strategy. Knowing the sources used to generate the material and how exhaustive the search was enables readers to assess whether this is a strength or a limitation (M6–M8).

- 3

The consensus process, detailing some of the issues we outline below:

- •

The method chosen to develop consensus and the different steps taken to get to agreement. There is no method considered the gold standard for consensus development. In consequence, it is important to describe the process clearly and transparently, especially if it was a modification of an existing method, so that readers can be aware of it and consider the potential for bias (M9–M11).

- •

The definition of consensus applied in the process (eg, number, percentage, or categorical rating, such as ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’), explaining the rationale for that definition and describing subsequent voting rounds (M12, M13).

- •

For each step, how responses were collected, and whether responses were collected in a group setting or individually. It is important to report whether responses were anonymous, as anonymity can minimize the potential influence by the group or dominant individuals. This information allows readers to consider the potential for bias, power dynamics and/or group influence to have shaped the consensus findings (M14).

- •

How responses were processed and/or synthesized. The choice of quantitative or qualitative methods for processing responses will be dictated by the consensus method being used, the format of statements or questions, and the overall aims of the consensus process (M15).

- •

Any piloting of the study materials and/or survey instruments, including how many individuals piloted the materials, their characteristics, any changes made as a result and whether their responses were used in the calculation of the final consensus (M16). If no pilot was conducted, this should be stated.

- •

How feedback was provided to panelists at the end of each consensus step or meeting. If provided, state whether feedback was quantitative (for example, approval rates per topic/item) and/or qualitative (for example, comments, or lists of approved items), whether it was anonymized, and, in the latter case, state whether anonymity was planned in the study design and what methods were used to guarantee it (M17, M18).

- •

Whether the steering committee or those managing consensus were involved in the decisions made by the consensus panel (eg, whether they had voting rights) (M19).

- •

- 4

Any financial or in-kind incentives used to encourage responses or participation in the consensus process (which need to be known because they could give rise to conflicts of interest) and any adaptations to make the surveys/meetings more accessible (eg, online meetings, plain language summaries) (M20, M21).

The timeframe of the consensus exercise should be reported, specifying the date of initiation, date of completion and duration of each consensus step, analysis and any extensions or delays in the analysis (R1). Any deviations from the study protocol should also be reported, explaining why they were necessary (R2).

Information should also be provided on the number of panelists, the response rate and the sociodemographic characteristics of participants, as it serves as a measure to assess how representative the panel is of the target population of the consensus (R3).

Last of all, the document must report the final outcome of the consensus process as qualitative data (eg, aggregated themes from comments that met the consensus threshold) and/or quantitative data (ag, summary statistics, score means, medians and/or ranges) (R4, R5).

DiscussionThis is the section used to discuss the strengths and limitations of the applied consensus method, addressing the representativeness of the panel, potential for feedback during consensus to bias responses and the potential impact of any non-anonymized interactions (D1). This section also presents the resulting consensus recommendations, discussing whether they are consistent with the previous literature on the subject (D2) and, if not, proposing reasons why the current process may have arrived at alternative conclusions.

Other informationIt is imperative to report endorsements/sponsors (O1), the potential conflicts of interests of the participants (O2), including the organizers and the panelists, and any involvement of funders in the design, process or publication of the consensus (O3). This information is crucial in making a rigorous critical appraisal of the consensus exercise.

Evaluation of a consensus document: critical appraisal and assessment of risk of biasOnce they are published, it is essential to assess the quality of consensus documents through a critical appraisal, analyzing its validity, relevance and applicability to the specific issue or circumstance that prompted the exercise.14 If the report is written in adherence to the recommendations of the appropriate guideline (ACCORD,2 in the case of consensus exercises), it will probably provide sufficient information to answer the key questions in its appraisal.15

Few tools are available to assist the critical appraisal of consensus exercises. In the case of consensus development conferences, a set of quality criteria has been proposed taking into account previously validated critical appraisal approaches.3,16 With a broader scope, the Joanna Briggs Institute has developed a critical appraisal tool for documents reporting expert opinion17,18 named “Textual evidence: Expert opinion” (directions for its use in the Spanish language are provided in the Manual JBI para la Síntesis de la Evidencia).19 It is composed of 6 questions, with four possible answer choices (yes, no, unclear, not applicable). The questions explore the following aspects:

- •

Clear identification of the source of the opinion

- •

The knowledge and experience of the authors in the field, as well as their affiliations with any type of organization.

- •

Whether the interests of the relevant population are the central focus of the opinion

- •

Logical defense/rationale of the conclusions.

- •

The reference to the extant literature.

- •

The congruence/incongruence with the literature and other sources of the opinion.

As is the case of any type of study, consensus exercises are susceptible to potential biases, both during the consensus development process and the writing of the final recommendations. Biases can be implicit or explicit. Implicit bias refers to the unconscious expectations of the participants, whereas explicit bias refers to the conscious and overt bias/expectations of the sponsors, organizers and participants of the consensus process.20 Particular attention should be devoted to:

- •

The employed consensus method, differentiating formal from informal approaches, as the latter, lacking a systematic methodology, are more prone to bias.

- •

Whether an exhaustive literature review and synthesis was carried out and its results made available to participants to prevent recommendations that are inappropriate based on the current evidence.

- •

The funding source, differentiating between public, nonprofit and private sponsorship. Industry-sponsored consensus exercises carry the highest risk of implicit and explicit bias.20

Information on the risk of bias must be provided and discussed in the Discussion section of the document, explaining the potential biases that may have affected the consensus and the measures the authors implemented to minimize them.

Note from the authorsIn this article, we used the terms response rate and completion rate for the sake of consistency, as they are the terms used in the literature on the subject of consensus exercises. Strictly speaking, however, these terms refer to proportions rather than rates.21

FundingThis research project did not receive specific financial support from funding agencies in the public, private or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

M. Salomé Albi Rodríguez, Albert Balaguer Santamaría, Carolina Blanco Rodríguez, Laura Cabrera Morente, Fernando Carvajal Encina, Jaime Cuervo Valdés, Eduardo Cuestas Montañés, M. Jesús Esparza Olcina, Sergio Flores Villar, Javier González de Dios, Rafael Martín Masot, M. Victoria Martínez Rubio, Manuel Molina Arias, Eduardo Ortega Páez, Begoña Pérez-Moneo Agapito, M. José Rivero Martín, Álvaro Gimeno Díaz de Atauri, Elena Pérez González and Juan Ruiz-Canela Cáceres.

Appendix A lists the remaining members of the Committee/Working Group on Evidence-Based Pediatrics.