In-home nursing care of the preterm newborn helps to bring the family situation to normal, promotes breastfeeding and development of the newborn, and enables the reorganisation of health care resources. The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate that in-home nursing care of the preterm newborn leads to an increase in weight and a similar morbidity.

Patients and methodologyA total of 65 cases and 65 controls (matched by weight, age and sex) were studied, all of them preterm newborns born in hospital and weighing less than 2100g at discharge. In-home nursing care was carried out by a paediatrician neonatologist, as well as two nurses specialised in neonatology who made several visits to the home. Weight gain was calculated as g/day and g/kg/day, comparing the first week of the study with the week prior to the beginning of the study.

ResultsThe groups were comparable. Weight gain in the group with home nursing care was 38g per day, significantly higher than the weight gain in the control group (31g/day). The independent predictive variables of the increase in g/kg/day during the study were in-home nursing care, male gender, breastfeeding less, and not having suffered from a peri-intraventricular haemorrhage. Neonatal morbidity was similar in both groups.

ConclusionsIn-home care was associated with a greater weight gain of the newborn at home than during their stay in the hospital, and can be considered safe because neonatal morbidity was not increased.

La atención domiciliaria de enfermería (ADE) del recién nacido prematuro próximo al alta en su propio domicilio en lugar del hospital normaliza la situación familiar, favorece la lactancia materna y el desarrollo del recién nacido y permite la reorganización de los recursos sanitarios. El propósito del presente trabajo es demostrar que el prematuro sometido al programa de ADE experimenta un aumento de peso superior en el domicilio respecto al hospital y no incrementa su morbilidad.

Pacientes y metodologíaEstudio comparativo de 65 casos y 65 controles (apareados por peso, edad y sexo), prematuros, de procedencia interna y con peso al alta inferior a 2.100g. La ADE fue administrada por un pediatra neonatólogo y 2 enfermeras especializadas en neonatología dependientes de los servicios hospitalarios, que realizaron visitas seriadas a domicilio. El aumento de peso se calculó por g/día y g/kg/día, comparando la semana previa al inicio del estudio con la primera semana del estudio.

ResultadosLos grupos fueron comparables. El aumento de peso en el grupo con ADE fue de 38g/día, significativamente superior al del grupo control (31g/día). Las variables independientes predictoras del «aumento en g/kg/día durante el estudio» fueron la ADE, el sexo varón, tomar menos lactancia materna y no haber padecido una hemorragia peri-intraventricular. La morbilidad neonatal fue similar.

ConclusionesLa ADE implicó un mayor aumento de peso del recién nacido en casa que durante su permanencia en el hospital, y no aumentó la morbilidad neonatal.

In-home nursing (IHN) care, that is, the care and follow-up of the newborn at his or her home rather than in the pre-discharge incubator at the hospital, is part of the new trends in neonatal care in developed countries1–4 such as the United States,5 countries in northern Europe6,7 and France.8 In Spain, the earliest references to it are from 1993 and 1997 in the Hospital 12 de Octubre of Madrid,9,10 which started an IHN programme in 1986.11 In Catalonia, the pioneering hospital was the Hospital Clínic (maternity unit), which started its programme in 2002.12 The available data suggest that the IHN programme improves the relationship and satisfaction of the parents, as it helps normalise the situation at home,13 promotes breastfeeding,14 and leads to increased weight gain, improved development15 and a decreased risk of infection in the newborn. It also allows for a higher degree of customisation in health education16 and a reorganisation of healthcare resources that is more satisfactory to the users. The reduction in the length of hospital stay can range from 417 to 17 days,18 and a previous study in our hospital found a reduction of 10.1 days,12 in which a newborn not receiving IHN care would have remained hospitalised inside a minimal care incubator, incurring all the associated healthcare staff costs.

In 2008 the American Academy of Paediatrics published a set of guidelines on the discharge of preterm infants based on the currently available scientific evidence.19 Some families refuse IHN care, possibly because they worry that they will not know how to properly care for their child. This refusal is more marked in families of preterm newborns with congenital malformations or severe complications,20 or preterm newborns whose care requires special techniques, such as gavage feeding or oxygen therapy. Parents are more likely to accept IHN care if they have received education and practised kangaroo care during the stay in the neonatal unit.21,22 Gavage feeding can be performed in a safe and efficacious manner during IHN care,23,24 achieving weight gains that may even exceed those considered satisfactory,23 and longer durations of breastfeeding.25 Psychosocial problems like anxiety or stress may develop in the family in the early days after discharge,26 impacting the quality of care.27 The nurse has to cooperate with the parents and guide them in the care of the child, offering not only his or her scientific knowledge and professional skills, but also a respectful approach to the feelings, attitudes, beliefs, and cultural values of the family.

The purpose of this study is to show that IHN care of the preterm newborn after early discharge fosters weight gain in the home, and is also safe, as it does not result in increased morbidity.

Patients and methodologyStudy designWe did a comparative case–control (1:1) study.28 For each newborn receiving IHN care included in the study, we included one other newborn that remained hospitalised in the neonatal unit (control), matched for birth weight, gestational age, corrected age at discharge, weight at discharge, and sex, to the degree that it was possible.

The study was approved by the ethics committee for clinical research in neonatology of the hospital, and the parents gave their informed consent for IHN.

PatientsWe enrolled neonates from the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona from 2007 to 2009 that met the following inclusion criteria: preterm birth (gestational age between 25 and below 37 weeks), born in the hospital, birth weight above 750g and discharge weight below 2100g (only for IHN cases), and with the following at the time of discharge (or of matching, for controls): absence of chromosomopathies or major malformations, corrected age≥30 weeks, stable temperature, lack of oral feeding difficulties, rising weight curve, good clinical condition, and family consent. We excluded preterm newborns with any relevant illness that could affect the evolution of their weight after discharge, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, congenital heart disease, or short bowel syndrome.

Protocol of in-home nursing careIn our programme, IHN care is delivered by providers associated with the hospital services, with a team consisting essentially of one neonatology paediatrician and 2 nurses specialised in neonatology that had been involved in the hospital care of the infant-family dyad. The programme started with 1 or 2 health education sessions for the parents of preterm newborns that were to receive IHN care, which informed them of the contents of the programme: hospital discharge of children with low weight that could be monitored at home in serial visits by an experienced nurse based off the neonatal unit until the final discharge. The parents were also educated about preterm neonates, with particular emphasis on corrected age, breastfeeding, kangaroo care, and the preparation for discharge and arrival at the home. The parents were given a tri-fold brochure on the care required by the newborn at the home that addressed feeding, sleep, weight control, the meaning of crying, prevention of sudden infant death, control of body and environmental temperature, dress, infection prevention, measures to take if living with pets, and recognition of warning signs. Parents were informed repeatedly that continuous support by telephone was available 24h a day. The parents had to accept this discharge plan voluntarily, and sign the corresponding consent form.

Study intervalOnce a patient was discharged early, a control of similar weight and with other similar characteristics was selected to match that case. When the control was discharged from the hospital with an approximate weight of 2000g, the corresponding case was also considered discharged, even though the case patient probably remained in IHN care, as final discharge in the programme is usually postponed until infants reach an approximate weight of 2100g.

Analysed variablesThe analysed variables are presented in the first column of Table 1 through 4. Weight gain in grams was calculated by the week, the day, and kg/day.

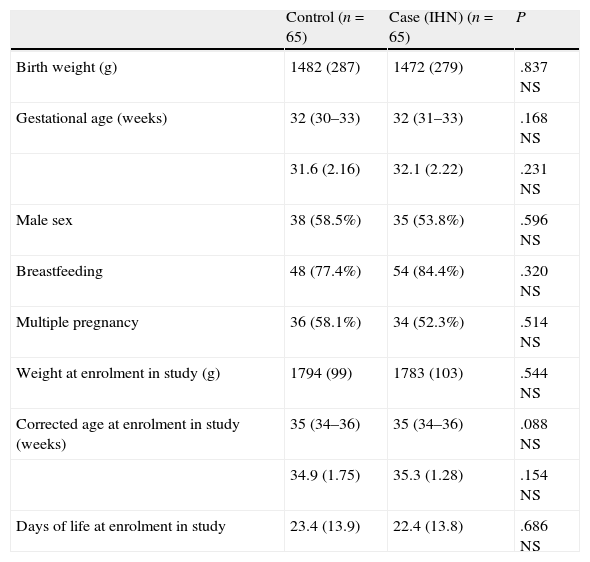

Matching and comparability of groups.

| Control (n=65) | Case (IHN) (n=65) | P | |

| Birth weight (g) | 1482 (287) | 1472 (279) | .837 NS |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 32 (30–33) | 32 (31–33) | .168 NS |

| 31.6 (2.16) | 32.1 (2.22) | .231 NS | |

| Male sex | 38 (58.5%) | 35 (53.8%) | .596 NS |

| Breastfeeding | 48 (77.4%) | 54 (84.4%) | .320 NS |

| Multiple pregnancy | 36 (58.1%) | 34 (52.3%) | .514 NS |

| Weight at enrolment in study (g) | 1794 (99) | 1783 (103) | .544 NS |

| Corrected age at enrolment in study (weeks) | 35 (34–36) | 35 (34–36) | .088 NS |

| 34.9 (1.75) | 35.3 (1.28) | .154 NS | |

| Days of life at enrolment in study | 23.4 (13.9) | 22.4 (13.8) | .686 NS |

Mean (SD); median (25th percentile–75th percentile); n (%).

The objective of the analysis was to: (1) compare the weight evolution of cases and controls from a week before the discharge (of cases), through the duration of the intervention (IHN) and at the end of the intervention; (2) analyse possible causes of the weight evolution in cases and controls; and (3) compare the morbidity in the case and control groups during the intervention period.

Parametric tests were used for quantitative variables that had a normal distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) and were homoscedastic (Snedecor's F-test), otherwise nonparametric tests were used. Parametric quantitative variables were described by means of the mean and standard deviation; nonparametric variables were expressed by the median, percentiles, and the interquartile range (25th percentile–75th percentile). The categories of qualitative variables were expressed as percentages. We compared parametric quantitative variables by means of Student's t test, and nonparametric variables with the Mann–Whitney U test. Qualitative variables were compared using the chi squared test or Fisher's exact test, whichever applied. The association between 2 quantitative variables was determined by means of Spearman's correlation coefficient. For the multivariate analysis, we performed a stepwise multiple linear regression to find the predictor variables that had the most significant independent influence on the dependent variable “weight gain in g/kg/day during the study interval”. We included all potential predictor variables that we had analysed, and particularly the study group (control: at hospital; case: at home).

Sample size calculationAfter recruiting the first 12 cases and 12 controls, we calculated the mean weight gain and its standard deviation for the latter group in g/kg/day during the period under study (mean, 20.6; standard deviation, 4.24) and calculated the sample size needed to detect a 10% improvement (in the two-tail test) in weight gain for an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 80%. We needed at minimum of 65 patients per group.

Proper matchingThere were no statistically significant differences for any of the variables, which show that the matching was done appropriately (Table 1).

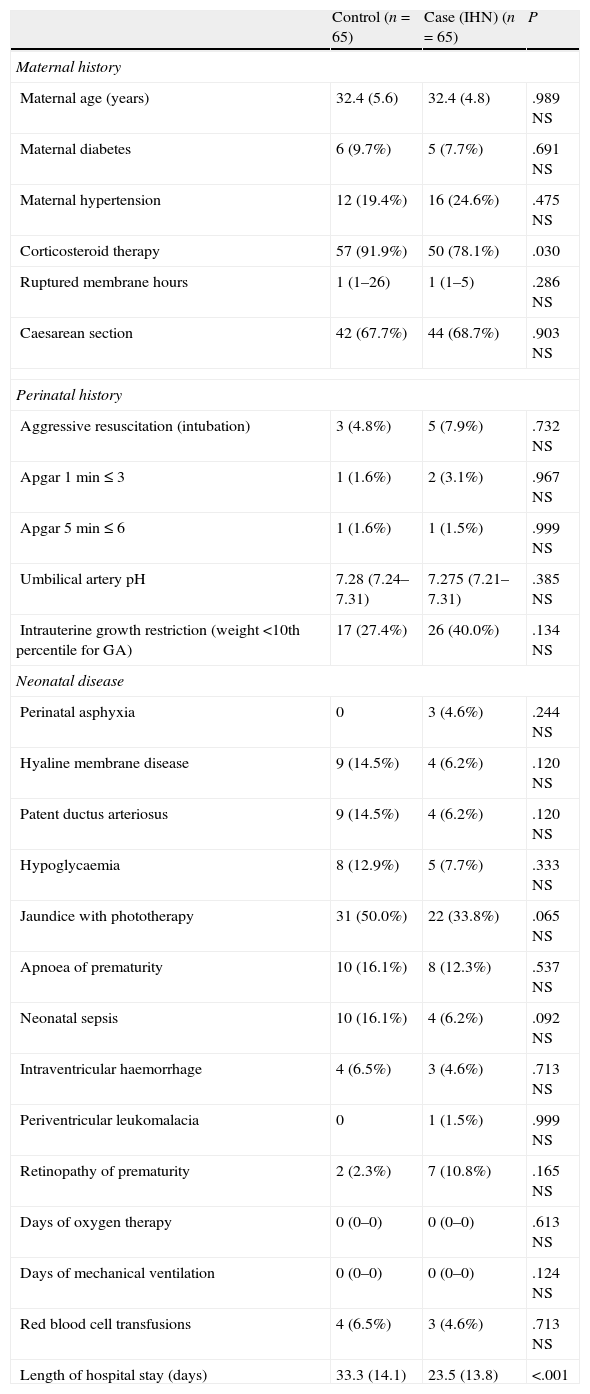

ResultsMedical history and illness during the neonatal period (Table 2)The only noteworthy finding was the lower exposure to antenatal corticosteroids in the case group. Both groups consisted of preterm newborns with few cases of hyaline membrane disease (few required oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation), patent ductus arteriosus, and intraventricular haemorrhage, and few required blood transfusions. The length of the hospital stay for the IHN group was 10 days shorter than in the control group, but the gestational age in the IHN group was 4 days greater.

Maternal and perinatal history and neonatal disease.

| Control (n=65) | Case (IHN) (n=65) | P | |

| Maternal history | |||

| Maternal age (years) | 32.4 (5.6) | 32.4 (4.8) | .989 NS |

| Maternal diabetes | 6 (9.7%) | 5 (7.7%) | .691 NS |

| Maternal hypertension | 12 (19.4%) | 16 (24.6%) | .475 NS |

| Corticosteroid therapy | 57 (91.9%) | 50 (78.1%) | .030 |

| Ruptured membrane hours | 1 (1–26) | 1 (1–5) | .286 NS |

| Caesarean section | 42 (67.7%) | 44 (68.7%) | .903 NS |

| Perinatal history | |||

| Aggressive resuscitation (intubation) | 3 (4.8%) | 5 (7.9%) | .732 NS |

| Apgar 1min≤3 | 1 (1.6%) | 2 (3.1%) | .967 NS |

| Apgar 5min≤6 | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (1.5%) | .999 NS |

| Umbilical artery pH | 7.28 (7.24–7.31) | 7.275 (7.21–7.31) | .385 NS |

| Intrauterine growth restriction (weight <10th percentile for GA) | 17 (27.4%) | 26 (40.0%) | .134 NS |

| Neonatal disease | |||

| Perinatal asphyxia | 0 | 3 (4.6%) | .244 NS |

| Hyaline membrane disease | 9 (14.5%) | 4 (6.2%) | .120 NS |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 9 (14.5%) | 4 (6.2%) | .120 NS |

| Hypoglycaemia | 8 (12.9%) | 5 (7.7%) | .333 NS |

| Jaundice with phototherapy | 31 (50.0%) | 22 (33.8%) | .065 NS |

| Apnoea of prematurity | 10 (16.1%) | 8 (12.3%) | .537 NS |

| Neonatal sepsis | 10 (16.1%) | 4 (6.2%) | .092 NS |

| Intraventricular haemorrhage | 4 (6.5%) | 3 (4.6%) | .713 NS |

| Periventricular leukomalacia | 0 | 1 (1.5%) | .999 NS |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | 2 (2.3%) | 7 (10.8%) | .165 NS |

| Days of oxygen therapy | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | .613 NS |

| Days of mechanical ventilation | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | .124 NS |

| Red blood cell transfusions | 4 (6.5%) | 3 (4.6%) | .713 NS |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 33.3 (14.1) | 23.5 (13.8) | <.001 |

Mean (DS); median (25th percentile–75th percentile); n (%).

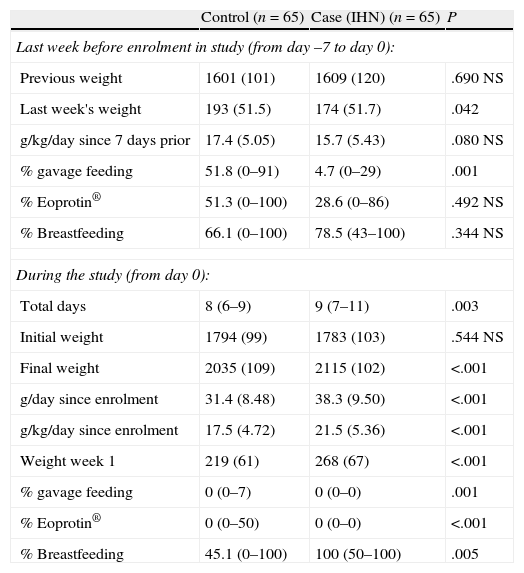

Both the weights the week prior to enrolling in the study and the initial weights once enrolled in the study were similar in cases and controls. However, the weight measurements did not coincide in time, as the final weight was taken on day 9 in cases and day 8 in controls. Thus, it was necessary to make these figures relative, measuring in g/kg/day for the week before discharge and the week of the study. The cases started with a weight similar to that of the controls, but ended the study with a much greater weight.

Weight changes and their possible causes.

| Control (n=65) | Case (IHN) (n=65) | P | |

| Last week before enrolment in study (from day –7 to day 0): | |||

| Previous weight | 1601 (101) | 1609 (120) | .690 NS |

| Last week's weight | 193 (51.5) | 174 (51.7) | .042 |

| g/kg/day since 7 days prior | 17.4 (5.05) | 15.7 (5.43) | .080 NS |

| % gavage feeding | 51.8 (0–91) | 4.7 (0–29) | .001 |

| % Eoprotin® | 51.3 (0–100) | 28.6 (0–86) | .492 NS |

| % Breastfeeding | 66.1 (0–100) | 78.5 (43–100) | .344 NS |

| During the study (from day 0): | |||

| Total days | 8 (6–9) | 9 (7–11) | .003 |

| Initial weight | 1794 (99) | 1783 (103) | .544 NS |

| Final weight | 2035 (109) | 2115 (102) | <.001 |

| g/day since enrolment | 31.4 (8.48) | 38.3 (9.50) | <.001 |

| g/kg/day since enrolment | 17.5 (4.72) | 21.5 (5.36) | <.001 |

| Weight week 1 | 219 (61) | 268 (67) | <.001 |

| % gavage feeding | 0 (0–7) | 0 (0–0) | .001 |

| % Eoprotin® | 0 (0–50) | 0 (0–0) | <.001 |

| % Breastfeeding | 45.1 (0–100) | 100 (50–100) | .005 |

Mean (SD); median (25th percentile–75th percentile); n (%).

The control group went on with gavage feeding, while the feeding tube was removed earlier in the IHN group. However, weight gain in the control group did not correlate to the percentage of gavage feeding (n=107; rho=0.037; p=0.075, not significant [NS]), with the number of feedings supplemented with Eoprotín® (n=69; rho=0.096; p=0.431, NS), or with the percentage of breastfeeding (or of artificial formula feeding) (n=69; rho=0.036; p=0.770, NS). In the period under study, none of the cases received gavage feeding or human milk fortifiers. However, the cases did breastfeed more.

The multivariate analysis yielded a corrected R2 of 0.452 (which means that the model accounts for 45.2% of the variance) and a P value below. 001. The independent variables selected in the resulting model and their non-standardized coefficients were: belonging to the case group (B=7.17; 95% CI 4.75–9.60; P<.001), percentage of breastfeeding (B=−0.053; 95% CI: −0.082 to −0.024; P<.001), presence of intraventricular haemorrhage (B=−5.39; 95% CI: −9.02 to −1.76; P<.004) and male sex (B=3.03; 95% CI: 0.62–5.43; P=.015).

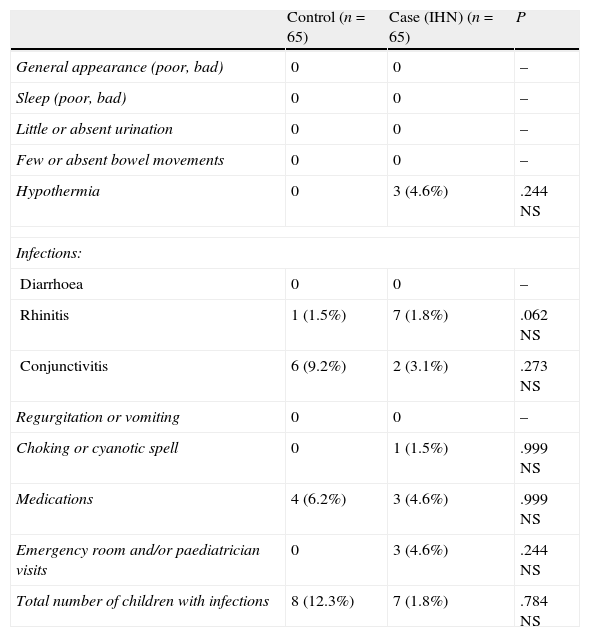

Comparison of incidence of disease and morbidity between cases and controls in the period under study (Table 4)A greater morbidity was not found in the cases (under IHN care).

Incidence of disease and morbidity during the study.

| Control (n=65) | Case (IHN) (n=65) | P | |

| General appearance (poor, bad) | 0 | 0 | – |

| Sleep (poor, bad) | 0 | 0 | – |

| Little or absent urination | 0 | 0 | – |

| Few or absent bowel movements | 0 | 0 | – |

| Hypothermia | 0 | 3 (4.6%) | .244 NS |

| Infections: | |||

| Diarrhoea | 0 | 0 | – |

| Rhinitis | 1 (1.5%) | 7 (1.8%) | .062 NS |

| Conjunctivitis | 6 (9.2%) | 2 (3.1%) | .273 NS |

| Regurgitation or vomiting | 0 | 0 | – |

| Choking or cyanotic spell | 0 | 1 (1.5%) | .999 NS |

| Medications | 4 (6.2%) | 3 (4.6%) | .999 NS |

| Emergency room and/or paediatrician visits | 0 | 3 (4.6%) | .244 NS |

| Total number of children with infections | 8 (12.3%) | 7 (1.8%) | .784 NS |

N (%).

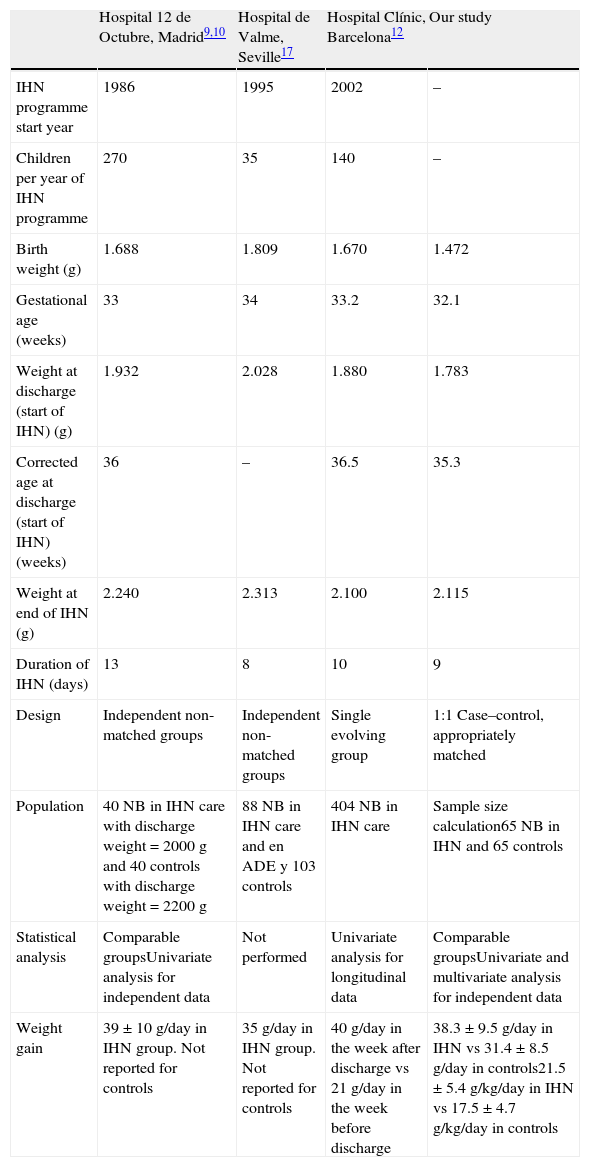

Previous studies have evaluated the IHN care of early-discharged preterm newborns,29–33 but our review of the literature did not uncover any case–control study with sufficient power to prove its potential benefits. Our study focused on the influence of IHN care on weight gain, which was greater in the home than at the hospital, after calculating the sample size required to obtain statistically significant conclusions (Table 5).

Comparisons between our study and other Spanish studies.

| Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid9,10 | Hospital de Valme, Seville17 | Hospital Clínic, Barcelona12 | Our study | |

| IHN programme start year | 1986 | 1995 | 2002 | – |

| Children per year of IHN programme | 270 | 35 | 140 | – |

| Birth weight (g) | 1.688 | 1.809 | 1.670 | 1.472 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 33 | 34 | 33.2 | 32.1 |

| Weight at discharge (start of IHN) (g) | 1.932 | 2.028 | 1.880 | 1.783 |

| Corrected age at discharge (start of IHN) (weeks) | 36 | – | 36.5 | 35.3 |

| Weight at end of IHN (g) | 2.240 | 2.313 | 2.100 | 2.115 |

| Duration of IHN (days) | 13 | 8 | 10 | 9 |

| Design | Independent non-matched groups | Independent non-matched groups | Single evolving group | 1:1 Case–control, appropriately matched |

| Population | 40 NB in IHN care with discharge weight=2000g and 40 controls with discharge weight=2200g | 88 NB in IHN care and en ADE y 103 controls | 404 NB in IHN care | Sample size calculation65 NB in IHN and 65 controls |

| Statistical analysis | Comparable groupsUnivariate analysis for independent data | Not performed | Univariate analysis for longitudinal data | Comparable groupsUnivariate and multivariate analysis for independent data |

| Weight gain | 39±10g/day in IHN group. Not reported for controls | 35g/day in IHN group. Not reported for controls | 40g/day in the week after discharge vs 21g/day in the week before discharge | 38.3±9.5g/day in IHN vs 31.4±8.5g/day in controls21.5±5.4g/kg/day in IHN vs 17.5±4.7g/kg/day in controls |

While IHN can be offered to term newborns, our study only included preterm newborns delivered at our hospital with a birth weight of 700g or greater, so the sample would be more homogeneous. In applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we selected a sample of preterm newborns that were fairly mature and with few instances of neonatal disease, which helped reach conclusions based solely on the IHN care and not on other intervening confounding variables. However, our sample is one of the most immature samples in the Spanish literature (Table 5). It is likely that the beneficial effects of IHN would extend to preterm newborns with chronic illnesses (such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia).

In making comparisons with other Spanish studies, we need to keep in mind that the weights at initiation and discontinuation of IHN care were different for each hospital (Table 5). This influenced the duration of IHN care and the estimated reduction in hospital stays. Logically, there are also differences in the corrected ages at discharge. To resolve these differences to the extent possible we calculated weight changes in g/kg/day.

Previous studies on IHN compare pre- and post-discharge weights in a single group of neonates participating in the programme, or compare the weight of 2 independent groups but without matching, and have always found greater weight gains in the IHN group. Esqué et al12 reported that the mean weight gain of a case in the IHN group for the 7 days before discharge was 21g/day, while it was 40g/day in the 7 days that followed discharge. The studies of Martín-Puerto et al9 and Gutiérrez-Benjumea et al17 only noted that in the IHN group the weight gains were 39g/day or 35g/day, respectively, providing no figures for the control group. Our study had a 1:1 case–control design, that is, there was one control for each case, matched by weight at discharge, birth weight, gestational age, age at discharge, and sex. To match the weight curves of each case with those of its control, we set day 0 of the study interval as that in which the weight of the control (who remained in the hospital) came the closest to the weight of the matched case. Thus, we made the case and control groups homogeneous and comparable. The weight gain of the IHN group was 38g/day, significantly higher than the weight gain of the control group (31g/day). Cruz et al.34 conducted a study similar to ours after 1995 in Cali, Colombia, although the weights at early discharge ranged between 1300 and 1350g.

In our study, the weights in the week prior to the beginning of the study and the weights at the beginning of the study were similar in cases and controls, a basic condition that needed to be met for the study to be valid. The weight gain at home was greater in the IHN group, perhaps because in these patients the weight gain in the last week in the hospital was lower than the weight gain in the control group. This lower gain was not due to differences in feeding, but probably due to various factors, among which are the less frequent use of gavage feeding in cases than in controls, as they were being prepared for discharge to the home by establishing full oral feeds. The fact that feeding tubes were not used in cases may have led to lower milk intakes and a greater energy expenditure in oral stimulation, which probably reduced their weight gain. Another aspect to consider that was not controlled was whether the newborn was in an incubator or a cot. In a Cochrane review, New et al.35 reported that weight gain may be reduced in preterm newborns that are transferred from an incubator to a cot due to increases in energy expenditure.

Setting our study apart from the remaining published studies, we attempted to determine which variables had a statistically significant and independent effect on the “weight gain in g/kg/day in the period under study”. Out of the 4 independent predictor variables, the most important was “being at home versus at hospital,” as it had the highest non-standardised coefficient (7.17) and standardised beta coefficient (0.609). Male sex also promoted weight gain during IHN care, a fact that is well known, as boys gain more weight than girls. The negative value of the percentage of breastfeeding in the multivariate analysis could be due to the fact that a lower intake of maternal milk is associated to a higher intake of artificial formula, which in turn leads to greater weight gains. In the case group, this effect of breastfeeding was counteracted by the beneficial effects on weight of being at home and by male sex. The one variable that resulted in decreased weight gain was the development of peri-intraventricular haemorrhage.

In short, IHN results in increased weight gain in the newborn that is at home rather than remaining hospitalised, and can be considered safe, as it is not associated with increased neonatal morbidity.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Álvarez Miró R, Lluch Canut MT, Figueras Aloy J, Esqué Ruiz MT, Arroyo Gili L, Bella Rodríguez J, et al. Evolución del peso del prematuro con alta precoz y atención domiciliaria de enfermería. An Pediatr (Barc). 2014;81:352–359.