Thirty-eight million patients with injuries are treated in Emergency Departments every year, 90% of them being in the form of unintentional injuries (UIs). There are currently no global records of its management in Spain, or the risk factors that may be associated with them. The objective of this study is to describe the management of UIs in Spanish paediatric emergency departments, and to analyse factors related to the presence of serious injuries.

Material and methodsA sub-study of a prospective multicentre observational study conducted over 12 months in 11 hospitals of the Spanish Paediatric Emergency Research Group (RiSEUP-SPERG), including children from 0 to 16 years of age consulting for UIs. Epidemiological data, circumstances of the injury, and data on emergency care and discharge destination were recorded on the 13th day of each month.

ResultsA total of 10,175 episodes were recorded, of which 1,941 were UIs 19.1%), including 1,673, of which 257 (15.4%) were severe. The most frequent complementary test was simple radiography (60.0%), and the most frequent procedure was limb immobilisation (38.6%). A significant relationship was found between presenting with a severe UI and age >5 years [OR 2.24 (95% CI: 1.61–3.16)], history of fracture [OR 2.05 (95% CI: 1.22–3.43)], or sports activity as a mechanism of injury [OR 1.76 (95% CI: 1.29–2.38)], among others.

ConclusionIn Spain, most UIs are not serious. X-rays and immobilisation of extremities are the most frequently performed tests and procedures. Severe UIs were associated with individual factors, such as age >5 years or history of fracture, and with sports activity as a mechanism associated with severity. It is vital to implement measures to improve the prevention of these injuries and to support the training of caregivers through educational programmes.

Cada año se tratan 38 millones de pacientes con lesiones en los servicios de Urgencias, siendo el 90% en forma de lesiones no intencionadas (LNI). Actualmente no existen registros globales de su manejo en España ni de los factores de riesgo que puedan llevar asociados. Nuestro objetivo es describir el manejo de las LNI en los servicios de Urgencias pediátricas (SUP) y analizar los factores relacionados con la presencia de lesiones graves.

Material y métodossubestudio de estudio observacional prospectivo multicéntrico desarrollado durante 12 meses, en 11 SUP de hospitales de la Red de Investigación de la Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (RiSEUP-SPERG), incluyéndose niños de 0 a 16 años de edad que consultan por una LNI, los días 13 de cada mes. Se registraron datos epidemiológicos, circunstancias de la lesión y datos sobre la atención en Urgencias y destino al alta.

ResultadosSe registraron 10.175 episodios, de los que 1.941 fueron LNI (19.1%), incluyéndose 1.673, de los cuales 257 (15.4%) fueron graves. La prueba complementaria realizada más frecuente fue la radiografía simple (60.0%) y el procedimiento más frecuente fue la inmovilización de extremidad (38.6%). Se encontró asociación significativa entre presentar una LNI grave y la edad >5 años [OR 2,24 (IC95% 1,61-3,16)], el antecedente de fractura [OR 2,05 (IC95% 1,22-3,43)] o la actividad deportiva como mecanismo lesional [OR 1,76 (IC 95% 1,29-2,38)], entre otros.

ConclusiónEn España, la mayoría de los casos de LNI no son graves. Las radiografías y la inmovilización de extremidades son las pruebas y procedimientos más frecuentemente realizados. La LNI grave se asoció con factores individuales, como la edad >5 años o el antecedente de fractura, y con la actividad deportiva como mecanismo asociado a gravedad. Resulta vital implementar medidas para mejorar la prevención de estas lesiones y apoyar la capacitación de los cuidadores mediante programas educacionales.

Based on global data published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2008, injuries are among the leading causes of mortality in the paediatric population worldwide, accounting for approximately 950 000 deaths in children and adolescents aged less than 18 years.1 Unintentional injuries (UIs) amount to 90% of these deaths.1 Although mortality in the paediatric population is substantially lower in developed countries, injuries continue to be a leading cause of death, accounting for approximately 40% of all child deaths.1

According to the EuroSafe 2017 study, each year an estimated 38 million patients receive care for injuries in emergency departments in Europe, of who 52% became injured at home or in the context of sports or leisure activities.2 Nearly 5 million hospital admissions in the European Union are due to injuries each year, and 33 million require outpatient treatment in emergency care settings.

In Spain, one study has analysed unintentional injuries managed at the primary care level3 and another has analysed the cases of children admitted to hospital following an accident,4 but there are no global data of the management of UIs in the paediatric population.

Unintentional injury is one of the leading causes of hospital admission and disability worldwide,5 and one indicator that can approximate the frequency of severe injury is the percentage of cases requiring hospital admission.

Factors have been identified that predict the risk of UI. Thus, the risk of injury and their severity vary based on individual characteristics (age, sex, behaviour), the family environment (socioeconomic status, family structure, siblings, parental characteristics) and certain factors related to the community.6 In the paediatric population, there is evidence that the under-1 population is at lower risk of injury, while children and young adults aged 1–4 years and 10–24 years are at higher risk of injury.2 Previous studies have also demonstrated that the children at highest risk of injury are those who are second in the sibling order, those who are alone in the house and those that receive chronic medication.3

The primary objective of our study was to describe the management of UIs in paediatric emergency departments (PEDs) in Spain, and the secondary objective was to analyse the risk factors associated with the occurrence of UIs.

Materials and methodsStudy designWe carried out a subordinate study in the context of a prospective multicentre observational study conducted over a period of 12 months in 11 PEDS of secondary and tertiary care hospitals (4 in the Basque Country, 3 in Catalonia, 2 in Castilla Leon, 1 in the Balearic Islands and 1 in the Community of Madrid) members of the Research Network of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Medicine) (RiSEUP-SPERG). The data corresponding to the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the sample have been published in a previous article.4

All participating hospitals recruited patients over a 1-year period, with data collection starting between September 2014 and January 2015.

Inclusion criteria- •

Children aged 0–16 years that sought care for an UI in any of the 11 PEDs of the participating secondary and tertiary hospitals on the 13th of each month. Of the 11 participating hospitals, 6 managed children up to age 14 years (age 14 excluded), 2 patients up to age 15 years, and another 3 patients up to 16 years (age 16 excluded).

- •

Patients for who we did not obtain informed consent.

- •

Intentional injury. The intent was evaluated by researchers in each hospital in adherence with the guidelines of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas.7

We collected epidemiological data (age, sex and personal history of fractures), data regarding the circumstances of the injury (mechanism of injury, setting, whether the injury was witnessed or not and, if witnessed, by who), data regarding management at the PED (triage acuity level, diagnostic tests and procedures performed, type of injury) and discharge destination.

Definitions- •

Unintentional injury (UI): event in which the injury occurs in a short period of time (seconds or minutes), the harmful outcome was not sought or the outcome was the result of one of the forms of physical energy in the environment or normal body functions being blocked by external means.8

- •

Intentional injury (II): injury produced as a result of violence, understood by the WHO as the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation.9

- •

Serious injury: UI leading to hospitalization, either in the ward or in the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU), due to the need of surgery or for other reason, bone fracture or luxation in an extremity, moderate or severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) (9–12 points or 3–8 points in the Glasgow Coma scale, respectively), second- or third-degree burns, craniofacial fractures, penetrating eye injury, drowning or near drowning and death within 24 h of the UI.

We collected data in an online form where we included all the visits related to an UI managed on the 13th of each month between 0 and 24 h in the participating PEDs. We chose the 13th of the month because it did not regularly fall on weekend days or holidays. The physician in charge of the patient entered the data in the online form by administering a questionnaire to the relatives of the patient during the patient’s stay in the PED. The principal investigators were the only staff with access to the raw data, which were stored in a virtual database. The coordinators of the study were responsible for safeguarding, processing and analyzing the data.

Patients were managed according to established protocols or the judgment of the physician in charge, and the performance of this study did not have any influence on clinical practice.

The study was approved by the clinical research ethics committee of each of the participating hospitals.

Statistical analysisWe have expressed qualitative data as absolute frequencies and percentages and quantitative data as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) based on the shape of the distribution. We assessed the shape of the distribution graphically by means of histograms and normal probability plots. We analysed the association between the presence of serious injury qualitative variables by means of the chi square test or Fisher exact test, and between serious injury and quantitative variables by means of the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test in the absence of a normal distribution. We assessed the strength of these associations with binary logistic regression methods, calculating odds ratios (ORs) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in the univariate and multivariate analyses. In the multivariate analysis, we included in the model those variables with a statistically significant association in the univariate analysis. We categorised age into 5 groups (<1 year, 1–4 years, 5–9 years, 10–14 years and 15–16 years). The statistical analysis was performed with the software SPSS version 21.0. We defined statistical significance as a p-value of less than 0.05.

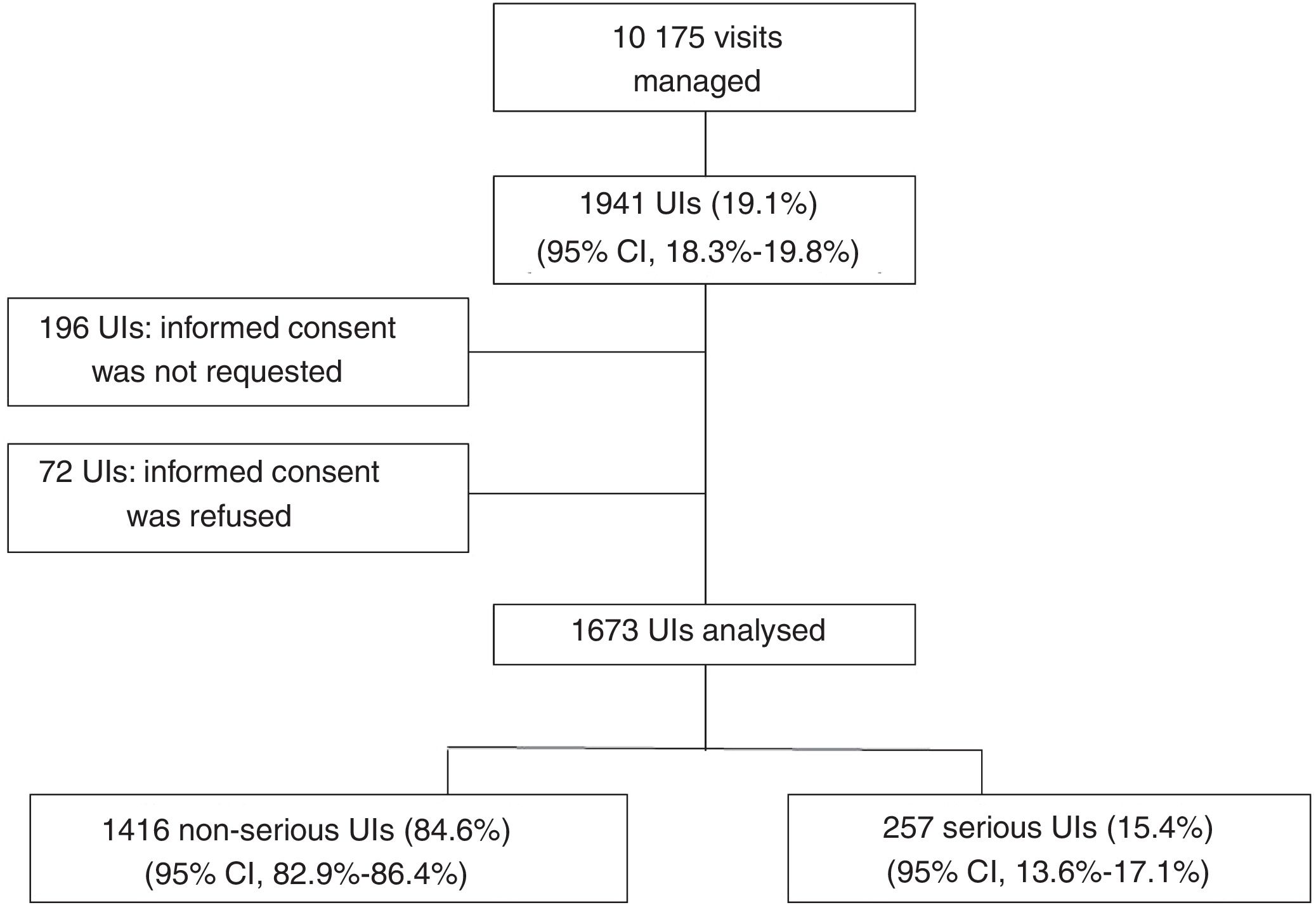

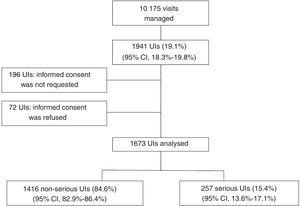

ResultsIn the dates included in the study, there were a total of 10 175 visits to the 11 PEDs, of which 1941 corresponded to children with UIs (19.1%; 95% CI, 18.3–19.8), of which we finally included 1673 cases (86.2%) in the study: 1416 (84.6%) were not serious, and 257 (15.4%) were serious (Fig. 1).

In the triage, 41 patients (2.5%) were classified as level 2, 266 (15.9%) as level 3, 1222 (73%) as level 4 and 144 (8.6%) as level 5. None of the patients was classified as level 1.

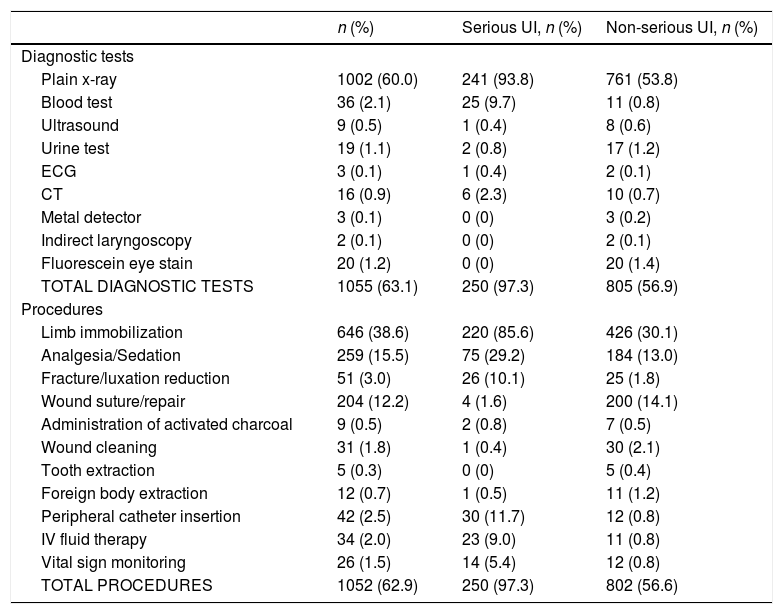

Table 1 summarises the diagnostic tests and the procedures performed in the emergency department. The diagnostic tests performed most frequently was the plain x-ray (60.0%): 517 upper extremity radiographs and 381 lower extremity radiographs. Immobilization was the most frequent procedure (38.6%): of the upper extremities in 371 cases, of the lower extremities in 264 cases and of more than 1 area in 11 patients with polytrauma.

Diagnostic tests and procedures performed in patients with unintentional injuries.

| n (%) | Serious UI, n (%) | Non-serious UI, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic tests | |||

| Plain x-ray | 1002 (60.0) | 241 (93.8) | 761 (53.8) |

| Blood test | 36 (2.1) | 25 (9.7) | 11 (0.8) |

| Ultrasound | 9 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 8 (0.6) |

| Urine test | 19 (1.1) | 2 (0.8) | 17 (1.2) |

| ECG | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.1) |

| CT | 16 (0.9) | 6 (2.3) | 10 (0.7) |

| Metal detector | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.2) |

| Indirect laryngoscopy | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.1) |

| Fluorescein eye stain | 20 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 20 (1.4) |

| TOTAL DIAGNOSTIC TESTS | 1055 (63.1) | 250 (97.3) | 805 (56.9) |

| Procedures | |||

| Limb immobilization | 646 (38.6) | 220 (85.6) | 426 (30.1) |

| Analgesia/Sedation | 259 (15.5) | 75 (29.2) | 184 (13.0) |

| Fracture/luxation reduction | 51 (3.0) | 26 (10.1) | 25 (1.8) |

| Wound suture/repair | 204 (12.2) | 4 (1.6) | 200 (14.1) |

| Administration of activated charcoal | 9 (0.5) | 2 (0.8) | 7 (0.5) |

| Wound cleaning | 31 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | 30 (2.1) |

| Tooth extraction | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.4) |

| Foreign body extraction | 12 (0.7) | 1 (0.5) | 11 (1.2) |

| Peripheral catheter insertion | 42 (2.5) | 30 (11.7) | 12 (0.8) |

| IV fluid therapy | 34 (2.0) | 23 (9.0) | 11 (0.8) |

| Vital sign monitoring | 26 (1.5) | 14 (5.4) | 12 (0.8) |

| TOTAL PROCEDURES | 1052 (62.9) | 250 (97.3) | 802 (56.6) |

CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; IV, intravenous, UI, unintentional injury.

Data expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages over the total for the specific type of injury. A single patient may have undergone more than 1 test or procedure.

Some form of sedation or analgesia was used in the management of 259 (15.5%) of the 1673 episodes of UI, corresponding to 75 of the patients with UIs classified as serious (29.2%) and 184 of the patients with UIs classified as not serious (13.0%).

Thirty-one patients were admitted to the hospital: 21 because they required surgery for fracture reduction, 4 for fractures that did not require surgery, 2 for TBI, 2 for poisoning, 1 for drowning/near drowning and 1 with a foreign body in the ear that required extraction under sedation in an operating room.

Three patients were admitted to the PICU: 1 with TBI, 1 with a craniofacial fracture, and 1 with poisoning.

Description of serious injuriesThere were 257 serious UIs. Of this total, 34 required hospital admission (3 to the PICU and 21 for surgical intervention); 240 corresponded to fractures and/or luxation in the extremities, 3 to moderate or severe TBI, 4 to craniofacial fractures and 1 to drowning/near drowning. There were no cases of second- or third-degree burns, penetrating eye trauma or death within 24 h of the injury.

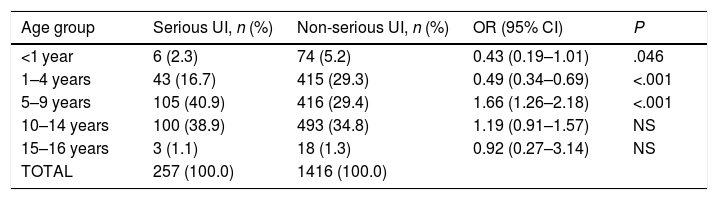

Factors associated with serious injuryTable 2 presents the risk of serious UI by age group. In the graphical analysis of the distribution of this variable, we established a cut-off point of 5 years, and found that children aged more than 5 years were at greater risk of incurring serious UIs compared to younger children, with an OR of 2.24 (95% CI, 1.61–3.16) (P < .001).

Risk of serious unintentional injury by age group.

| Age group | Serious UI, n (%) | Non-serious UI, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 6 (2.3) | 74 (5.2) | 0.43 (0.19–1.01) | .046 |

| 1–4 years | 43 (16.7) | 415 (29.3) | 0.49 (0.34–0.69) | <.001 |

| 5–9 years | 105 (40.9) | 416 (29.4) | 1.66 (1.26–2.18) | <.001 |

| 10–14 years | 100 (38.9) | 493 (34.8) | 1.19 (0.91–1.57) | NS |

| 15–16 years | 3 (1.1) | 18 (1.3) | 0.92 (0.27–3.14) | NS |

| TOTAL | 257 (100.0) | 1416 (100.0) |

CI, confidence interval; NS, not significant; OR, odds ratio; UI, unintentional injury.

Data expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages over the total for the specific type of injury.

We also found an association of serious injury with a previous history of fracture (26.3% serious with a history of fracture vs 14.8% serious without a history of fracture), con a OR of 2.05 (95% CI, 1.22–3.43) (P = .006).

The presence of the mother was a protective factor (11.5% witnessed serious injuries vs 16.5% unwitnessed serious injuries), with an OR of 0.64 (95% CI, 0.46–0.89) (P = .006).

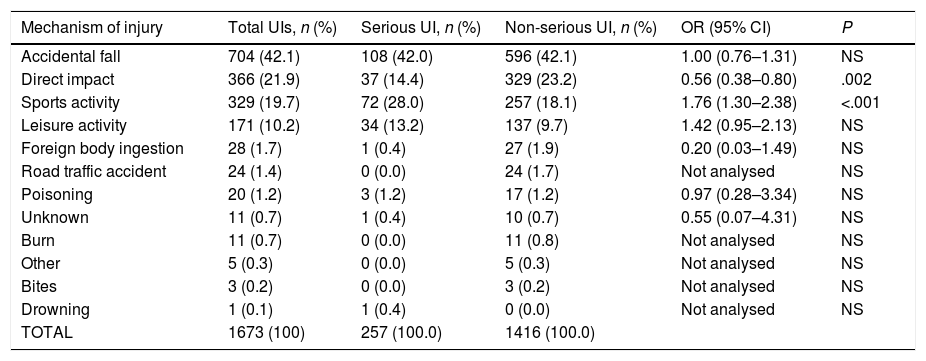

Table 3 presents the risk of serious UI by mechanism of injury, and we found a statistically significant difference in sports-related activities, which constituted a risk factor, with an OR of 1.76 (95% CI, 1.30–2.38) (P < .001), and in direct impact trauma, which behaved as a protective factor, with an OR of 0.56 (95% CI, 0.38-0.80) (P = .002).

Mechanisms of injury and risk of serious unintentional injury by mechanism of injury. Univariate analysis.

| Mechanism of injury | Total UIs, n (%) | Serious UI, n (%) | Non-serious UI, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accidental fall | 704 (42.1) | 108 (42.0) | 596 (42.1) | 1.00 (0.76–1.31) | NS |

| Direct impact | 366 (21.9) | 37 (14.4) | 329 (23.2) | 0.56 (0.38–0.80) | .002 |

| Sports activity | 329 (19.7) | 72 (28.0) | 257 (18.1) | 1.76 (1.30–2.38) | <.001 |

| Leisure activity | 171 (10.2) | 34 (13.2) | 137 (9.7) | 1.42 (0.95–2.13) | NS |

| Foreign body ingestion | 28 (1.7) | 1 (0.4) | 27 (1.9) | 0.20 (0.03–1.49) | NS |

| Road traffic accident | 24 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (1.7) | Not analysed | NS |

| Poisoning | 20 (1.2) | 3 (1.2) | 17 (1.2) | 0.97 (0.28–3.34) | NS |

| Unknown | 11 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 10 (0.7) | 0.55 (0.07–4.31) | NS |

| Burn | 11 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (0.8) | Not analysed | NS |

| Other | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.3) | Not analysed | NS |

| Bites | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | Not analysed | NS |

| Drowning | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | Not analysed | NS |

| TOTAL | 1673 (100) | 257 (100.0) | 1416 (100.0) |

CI, confidence interval; NS, not significant; OR, odds ratio; UI, unintentional injury. Not analysed: could not be determined due to observed frequency = 0.

Data expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages.

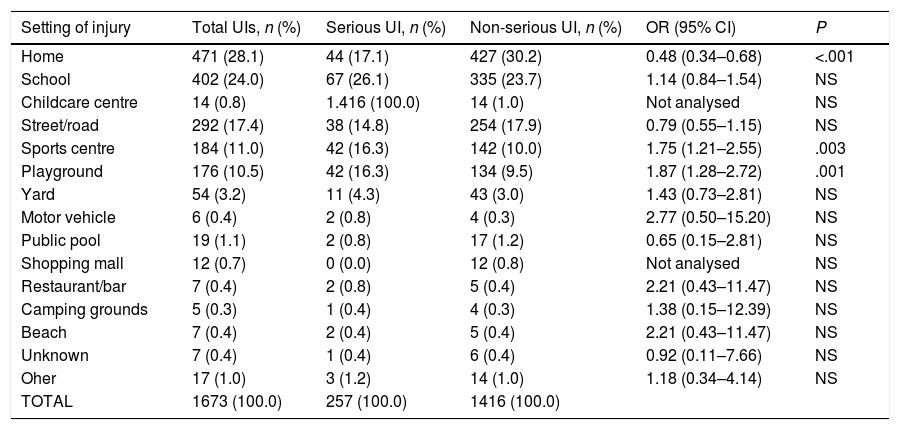

When it came to the setting where the UI took place (Table 4), we found statistically significant increases in risk in sports facilities, with an OR of 1.75 (95% CI, 1.21–2.55) (P = .003), and in playgrounds, with an OR of 1.87 (95% CI, 1.28–2.72) (P = .001). On the other hand, the home setting was a protective factor, with an OR of 0.48 (95% CI, 0.34-0.68) (P < .001).

Settings where serious unintentional injuries occurred, and risk of serious injury by setting.

| Setting of injury | Total UIs, n (%) | Serious UI, n (%) | Non-serious UI, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | 471 (28.1) | 44 (17.1) | 427 (30.2) | 0.48 (0.34–0.68) | <.001 |

| School | 402 (24.0) | 67 (26.1) | 335 (23.7) | 1.14 (0.84–1.54) | NS |

| Childcare centre | 14 (0.8) | 1.416 (100.0) | 14 (1.0) | Not analysed | NS |

| Street/road | 292 (17.4) | 38 (14.8) | 254 (17.9) | 0.79 (0.55–1.15) | NS |

| Sports centre | 184 (11.0) | 42 (16.3) | 142 (10.0) | 1.75 (1.21–2.55) | .003 |

| Playground | 176 (10.5) | 42 (16.3) | 134 (9.5) | 1.87 (1.28–2.72) | .001 |

| Yard | 54 (3.2) | 11 (4.3) | 43 (3.0) | 1.43 (0.73–2.81) | NS |

| Motor vehicle | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (0.3) | 2.77 (0.50–15.20) | NS |

| Public pool | 19 (1.1) | 2 (0.8) | 17 (1.2) | 0.65 (0.15–2.81) | NS |

| Shopping mall | 12 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (0.8) | Not analysed | NS |

| Restaurant/bar | 7 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (0.4) | 2.21 (0.43–11.47) | NS |

| Camping grounds | 5 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.3) | 1.38 (0.15–12.39) | NS |

| Beach | 7 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 5 (0.4) | 2.21 (0.43–11.47) | NS |

| Unknown | 7 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (0.4) | 0.92 (0.11–7.66) | NS |

| Oher | 17 (1.0) | 3 (1.2) | 14 (1.0) | 1.18 (0.34–4.14) | NS |

| TOTAL | 1673 (100.0) | 257 (100.0) | 1416 (100.0) |

CI, confidence interval; NS, not significant; OR, odds ratio; UI, unintentional injury.

Not analysed: could not be determined due to observed frequency = 0.

Data expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages over the total for the specific type of injury.

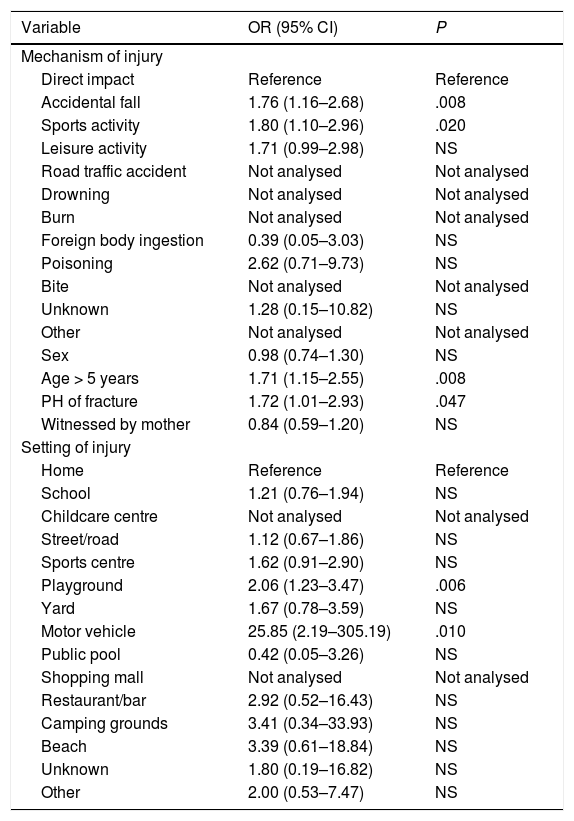

In the multivariate analyses (Table 5), the reference category was direct impact in the analysis of the mechanisms of injury, and the home in the analysis of the setting of injury. We found a significantly higher risk of serious UI in case of accidental falls or sports-related injuries and an increase in risk that was not statistically significant associated with leisure activities. Similarly, when it came to the setting of injury, we found an increased risk associated with motor vehicles and playgrounds. The associations of serious injury with age greater than 5 years and a previous history of fracture remained significant in the multivariate analysis.

Risk factors for serious unintentional injury. Multivariate analysis.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of injury | ||

| Direct impact | Reference | Reference |

| Accidental fall | 1.76 (1.16–2.68) | .008 |

| Sports activity | 1.80 (1.10–2.96) | .020 |

| Leisure activity | 1.71 (0.99–2.98) | NS |

| Road traffic accident | Not analysed | Not analysed |

| Drowning | Not analysed | Not analysed |

| Burn | Not analysed | Not analysed |

| Foreign body ingestion | 0.39 (0.05–3.03) | NS |

| Poisoning | 2.62 (0.71–9.73) | NS |

| Bite | Not analysed | Not analysed |

| Unknown | 1.28 (0.15–10.82) | NS |

| Other | Not analysed | Not analysed |

| Sex | 0.98 (0.74–1.30) | NS |

| Age > 5 years | 1.71 (1.15–2.55) | .008 |

| PH of fracture | 1.72 (1.01–2.93) | .047 |

| Witnessed by mother | 0.84 (0.59–1.20) | NS |

| Setting of injury | ||

| Home | Reference | Reference |

| School | 1.21 (0.76–1.94) | NS |

| Childcare centre | Not analysed | Not analysed |

| Street/road | 1.12 (0.67–1.86) | NS |

| Sports centre | 1.62 (0.91–2.90) | NS |

| Playground | 2.06 (1.23–3.47) | .006 |

| Yard | 1.67 (0.78–3.59) | NS |

| Motor vehicle | 25.85 (2.19–305.19) | .010 |

| Public pool | 0.42 (0.05–3.26) | NS |

| Shopping mall | Not analysed | Not analysed |

| Restaurant/bar | 2.92 (0.52–16.43) | NS |

| Camping grounds | 3.41 (0.34–33.93) | NS |

| Beach | 3.39 (0.61–18.84) | NS |

| Unknown | 1.80 (0.19–16.82) | NS |

| Other | 2.00 (0.53–7.47) | NS |

CI, confidence interval; NS, not significant; OR, odds ratio; PH, previous history; UI, unintentional injury.

Not analysed: could not be determined due to observed frequency = 0.

Data expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages.

Injuries are a frequent reason for PED visits in Spain, and 90% of UIs could be prevented.10 In addition, injuries are the leading cause of death in the paediatric population in the European Union (9100 deaths a year in individuals aged less than 20 years), and 2/3 of these injuries are unintentional.10

In 2012, the European Child Safety Alliance published a study of the measures proposed and implemented by different European countries (Europa 31) to reduce child and adolescent mortality due to UIs. Spain is among the countries with the best outcomes (ranking 10th out of the 31 countries included) in nearly all areas except fall prevention.10

In our study, nearly 20% of emergency visits were due to UIs, which was consistent with other studies that have shown an increase in the number of visits to PEDs for this reason.11 This is the first study conducted in the PED setting that describes the diagnostic tests used and the rate of hospital admission due to UI and analysing the circumstances that may lead to poorer outcomes. These parameters can be good indicators of the social cost of UIs, which have been estimated to result in the cumulative loss of 40 938 life years of children and adolescents that will not grow, learn or contribute to society.12

We found that slightly more than 15% were serious injuries, in agreement with previous case series in Spain.13 In developing countries, the proportion of admission nears 50%,14 but it is lower in other countries, such as the United States (30%),15 Argentina (22.9%),16 Brazil (8.5%)17 and other Spanish studies (13.7%),18 although it was still much higher compared to our study, which found a proportion of 1.6%. Possible explanations for this difference would be that studies in those countries may not have included milder injuries or may not have included all patients managed in the PED, or that the true proportion of severe injuries was actually greater. On the other hand, the low proportion of severe injuries found in our study stood in contrast with the high number of x-rays performed in our series (nearly 60% of cases), which may reflect a certain degree of defensive medicine. This finding reveals exposure to a significant amount of radiation and the associated risk of developing malignancies later in life. We did not analyse the appropriateness of these examinations, but the study reflects the usual clinical practice in PEDs at different levels of care. The use of ultrasound for diagnosis of long bone fractures would reduce the use of x-rays in the evaluation of these patients.19

A finding worth highlighting in our study was the low proportion of patients with UIs that received sedation and analgesia in the PED (15.5% of the total and 29.2% of the group with severe injuries). Although paediatricians are increasingly aware of this issue, there are many factors that contribute to the lag in the use of sedation and analgesia in the paediatric population at the emergency care level. Some of these factors are the diversity of specialists that manage these patients (orthopaedists, paediatric emergency physicians, family physicians, etc.), as was the case in our study, or that appropriate scales for pain assessment are not routinely used.

As had been previously described,17 a previous history of fractures was associated with an increased risk of severe injury, which could reflect a more “restless” behaviour on the part of these patients. A study conducted in the primary care setting in Spain found that 25% of families believed their children exhibited sensation-seeking behaviours and that fractures were the most common type of injury in this group of children.3

In Europe, 3.6 million sports-related injuries are managed each year at the hospital level, with a peak in incidence in the group aged 10–19 years.20 There is evidence of a decrease in mortality associated with the implementation of safety programmes and campaigns for extreme sports, but on the other hand the practice of sports has increased and with it sports-related injuries.20 Our study found that sports-related and playground activities were risk factors for serious injury. Thus, it may be useful to develop programmes for the prevention of UIs in sports activities in schools and for adequate training in UI prevention of staff overseeing outdoor activities. We carried out our study in public hospitals, so we may have underestimated the incidence of sports-related injuries, as in many instances the health insurance policies covering this type of injury refer patients to private health care facilities.

Spain is still underperforming in certain aspects related to sports and physical activity.10 According to the 2012 Child Safety Report Card,12 although there are national policies and legislation requiring the use of bicycle helmets when cycling, they are only partially enforced; there is no law requiring fencing around any form of private pool (current Spanish law on the subject is at the autonomous community level and varies based on the regulations of each of these regions) and there is no national strategy for the prevention of injuries involving water safety.21

Accidental falls were the most frequent mechanism of injury in our sample4 and in most other published case series14,15,18,22,23 and carry a higher risk of serious injury, but there is no law banning the distribution and sale of walkers (associated with a higher incidence of falls),24 regulating the use of window guards or locks or guardrails in balconies and stairs, and no policy has been implemented to facilitate access to childcare equipment for disadvantaged families. A national strategy with specific targets and timelines needs to be devised for the prevention of falls in children and adolescents. All these improvements refer to the home setting as, as our study evinced, the family home was the most frequent setting of UIs.

While motor vehicles corresponded to a low frequency of UIs in our case series, they constituted a risk. Royal Decree 667/2015, of 17 July25 that amended the General Regulation on Traffic (approved in Royal Decree 1428/2003, of 21 November), regulates the use of safety belts, approved child restraint systems and the facing of these restraint systems relative to the normal direction of travel of the vehicle. The actual enactment of these safety regulations is in different stages when it comes to manufacturers and retailers. All the regulations currently in place are far from adhering to European recommendations to enact laws requiring children aged less than 13 years to ride in the back seats of vehicles, or children aged less than 4 years to be placed in restraint systems facing backward,10 although evaluating the actual degree of adherence to current law would require a specific study.

There are limitations to our study. On one hand, while 11 hospitals in different regions participated, the sample did not include PEDs from every health area in Spain, and therefore the results should be extrapolated with caution to regions that were not represented in the study. Furthermore, there were differences in the age range served by participating PEDs, as some hospitals served children up to the 14th birthday, others up to the 15th birthday and others up to the 16th birthday, which means that the incidence of injuries in the upper range of age was probably underestimated. We did not use validated severity scales because currently available scales (such as the Pediatric Trauma Score [PTS]) do not include UIs other than traumatic injury that were included in our analysis. Lastly, the study was conducted in PEDs, which presumably are the setting where patients with the most serious or concerning injuries are managed. When it comes to the development of preventive strategies, UIs managed in other settings, especially primary care, should also be taken into account. Nevertheless, we believe that the information obtained from PEDs is essential for the development of appropriate preventive measures.

In conclusion, UIs continue to be a frequent reason for visits to PEDs in Spain, although in most cases these injuries are not serious. The use of x-rays for diagnosis and immobilization for management of injuries was frequent in the paediatric emergency care setting. The risk of serious UI in children was mainly associated with patient-related factors (individual behaviours or characteristics), such as age greater than 5 years or a previous history of fracture, as well as factors related to the social environment of the child (leisure and physical activities). Thus, it is essential that nationwide policies and strategies are implemented to improve the prevention of UIs at home or in means of transport and the skills of caregivers and health care providers by means of educational interventions.

FundingThere were no external sources of funding for this article or the preceding research.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Eduardo J. Bardón Cancho, Paediatric Emergency Section, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain.

Cristina Arribas Sánchez, Paediatric Emergency Section, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain.

Arístides Rivas García, Paediatric Emergency Section, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain.

Rafael Marañón Pardillo, Paediatric Emergency Section, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain.

Santiago M. Fernández, Paediatric Emergency Department, Hospital Universitario de Cruces, Bizkaia, Spain.

Santiago Mintegi, Paediatric Emergency Department, Hospital Universitario de Cruces, Bizkaia, Spain.

Anaida Obieta, Paediatric Emergency Department, Hospital Universitario Son Espases, Balearic Islands, Spain.

Nuria Chaves, Paediatric Emergency Department, Hospital Universitario Donostia, Gipuzkoa, Spain.

Claudia Farrés, Paediatric Emergency Department, Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí, Sabadell, Barcelona, Spain.

Gloria Estopiñá, Paediatric Emergency Department, Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa, Terrassa, Barcelona, Spain.

Fernando David Panzino, Paediatric Emergency Department, Hospital General del Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain.

Helvia Benito, Paediatric Emergency Department, Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles, Avila, Spain.

Leticia González, Paediatric Emergency Department, Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid, Spain.

María Amalia Pérez, Paediatric Emergency Department, Hospital de Zumárraga, Gipuzkoa, Spain.

Agustín Rodríguez, Paediatric Emergency Department, Hospital Alto Deba, Gipuzkoa, Spain.

En el anexo se relacionan los nombres de todos los autores del artículo.

Please cite this article as: Bardón Cancho EJ, et al. Manejo y factores de riesgo de gravedad asociados a lesiones no intencionadas en urgencias de pediatría en España. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;92:132–140.