Edited by: Fernando Santos-Simarro. Molecular Diagnostic and Clinical Genetics Unit University Hospital Son Espases. Palma de Mallorca. Spain

Last update: January 2026

More infoThe implementation of pharmacogenetics in Spain has experienced a significant boost in the last year, driven by the update of the genetic services portfolio of the National Health System, the national Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) biomarker database and the development and update of clinical guidelines by scientific societies and expert groups. However, the scope of this implementation is quite limited in the pediatric population because most studies do not include children, which in turn means that, in many cases, guidelines do not specify what to do in this population. This article reviews the tests included in the Common Portfolio of Genetic Services, drugs with pharmacogenetic recommendations in technical data sheets, and the main global and national pharmacogenetic guidelines, extracting and analyzing the existing information for the pediatric population. Drug-gene pairs with greater use in pediatrics are presented in more detail, such as proton pump inhibitors and CYP2C19, Abacavir, allopurinol, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin with HLA-A and HLA-B genes, voriconazole and CYP2C19, tacrolimus and CYP3A5, aminoglycosides and MT-RNR1, thiopurines and TMPT/NUDT15, or atomoxetine and CYP2D6. Despite current limitations, the use of pharmacogenetics in pediatrics can and should be implemented in those cases where regulatory agencies and/or scientific societies recommend it.

La implementación de la farmacogenética en España ha sufrido un extraordinario impulso en el último año con la actualización de la cartera de servicios de genética del Sistema Nacional de Salud, la publicación de la base de datos nacional de biomarcadores farmacogenéticos en las fichas técnicas de los medicamentos y la generación y actualización de guías clínicas por parte de sociedades científicas y consorcios de expertos. Sin embargo, el alcance de esta implementación está bastante limitada en la población pediátrica debido a que la mayoría de los estudios que se hacen no incluyen a niños, lo que a su vez hace que, en muchas ocasiones, las guías no especifiquen qué hacer en esta población. En este artículo se revisan las pruebas incluidas en la Cartera Común de Servicios de genética, los fármacos con recomendación farmacogenética en ficha técnica y las principales guías mundiales y nacionales de recomendaciones farmacogenéticas y se extrae y analiza la información existente para la población pediátrica. Se presentan en mayor detalle aquellos pares fármaco/gen con un mayor uso en pediatría, como inhibidores de la bomba de protones y CYP2C19, abacavir, alopurinol, carbamazepina, oxcarbazepina y fenitoína con los genes HLA-A y HLA-B, voriconazol y CYP2C19, tacrolimus y CYP3A5, aminoglucósidos y MT-RNR1, tiopurinas y TMPT/NUDT15, y atomoxetina y CYP2D6. A pesar de las limitaciones, el uso de la farmacogenética en pediatría puede y debe implementarse en aquellos casos en que las agencias reguladoras, y/o las sociedades científicas así lo recomiendan.

Pharmacogenetics studies how genetic variation impacts pharmacological treatment both in terms of efficacy and drug-induced toxicity. In recent years, there have been substantial advances in the field thanks to the performance of clinical trials and observational studies. However, specific data for the pediatric population is scarce. If we specifically focus on pharmacogenetics, a search in PubMed using the terms ((pharmacogenetics) OR (pharmacogenomics)) AND ((children) OR (pediatrics) OR (pediatry)) yielded a total of 4732 records as of July 19, 2024. In contrast, the search strategy ((pharmacogenetics) OR (pharmacogenomics)) NOT ((children) OR (pediatrics) OR (pediatry)) yielded 34 180 records. This reflects the extent to which the pediatric population is underrepresented in pharmacogenetic trials and, in consequence, the dearth of information currently available to apply pharmacogenetics to pediatric care.

In Spain, two recent milestones have promoted rapid advances in the availability and use of pharmacogenetic tests in the National Health System (NHS). The first one was the approval on June 23, 2023 by the Interterritorial Council of the NHS of the update to the genetic test catalog of the nationwide service portfolio of the public health care system, subsequently ratified by Order SND/606/2024 of June 13, 2024, which includes tests for 672 gene-disease associations or target regions that would be covered for any patient in the NHS, 33 of them in the field of pharmacogenomics. The second was the launch of the pharmacogenomic biomarker database of the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS, Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices) on July 29, 2024. The aim of this database is to facilitate access to the information contained in summaries of product characteristics (SmPCs) to promote the application of pharmacogenetics to clinical practice.1

It is important to note that none of these initiatives distinguish between adult and pediatric patients, so all drugs and indications included that affect the pediatric population are likely to be applicable to this population. Nevertheless, there are important limitations in this regard. As noted above, the limited evidence from specific studies supporting their clinical utility in the pediatric populations is one of the chief limitations. Another significant limitation involves the impact of the maturation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters on drug response.2 For example, cytochromes CYP2D6 and CYP2C19, which are involved in the metabolism of a large number of drugs, undergo a prolonged maturation process that starts in the fetal period.3 Their enzymatic activity at birth is not equivalent to their activity in adulthood, so the clinical impact of variants in the CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 in the first months of life remains unknown.

The aim of this article is to guide the implementation of pharmacogenetics in pediatric care and contribute to updating the knowledge of pediatric care providers on the relevant pharmacogenetic data currently available for drugs used in the pediatric population. To this end, we conducted an exhaustive review of the pharmacogenomic test catalog of the Ministry of Health and of the AEMPS database, highlighting the frequent indications and uses in the pediatric population. We also reviewed and summarized the recommendations for the implementation of clinical pharmacogenomics in pediatric care included in the main pharmacogenetics guidelines that are currently available, such as those of the Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium (CPIC), the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group and the Spanish Society of Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics, with particular emphasis on the most useful dosage adjustment recommendations based on the available evidence and the frequency the drugs are used in the pediatric population.

Knowledge of these associations and its appropriate application to the prescribing/contraindication or dosage of these drugs is key in order to improve the safety and effectiveness of treatments in the pediatric population. We hope that this information will be useful and facilitate the implementation of pharmacogenetics in pediatric care.

Pharmacogenetics in the Spanish NHS: nationwide portfolio of genetics services and drugs with pharmacogenetic indications in summaries of product characteristicsThe pharmacogenomic biomarker database of the AEMPS includes 78 gene-drug pairs for 68 active ingredients involving 18 different genes. According to the website of the AEMPS, the information contained in this database is based on the gene-drug pairs supported by level 1A evidence documented in the database pharmgkb.org as of June 2024 and pairs for whom information is not available in the SmPC but are included in the nationwide genetic and genomic test portfolio of the Spanish Ministry of Health. Table 1summarizes the information for the 19 drugs or drug families and the 12 genes for which the pharmacogenomic test catalog notes the indications for the test.

Summary of the pharmacogenomic tests included in the genetics service portfolio of the Spanish National Health System.

| Drug | Biomarker/gene | Indication for pharmacogenomic testing |

|---|---|---|

| Abacavir | HLA-B*57:01 | Candidates for treatment with abacavir (testing required per SmPC) |

| Voriconazole | CYP2C19 | Prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in high-risk allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Limited to cases of suspected lack of response to treatment and/or suspected adverse drug reaction |

| Atazanavir | CYP2C19, UGT1A1 | Candidates for treatment with atazanavir concurrent with voriconazole and ritonavir (testing required per SmPC) |

| Fluoropyrimidines | DPYD | Candidates for treatment with fluoropyrimidines (testing required per SmPC) |

| Irinotecan | UGT1A1 | Candidates for treatment with irinotecan |

| Thiopurines | TPMT, NUDT15 | Candidates for treatment with thiopurines |

| Carbamazepine | HLA-A*31:01, HLA-B*15:02 | Candidates for treatment with carbamazepine and at risk of a serious adverse event: 1) Asian ancestry; 2) personal or family history of skin toxicity induced by other drugs; 3) previous severe cutaneous adverse reaction induced by carbamazepine. |

| Phenytoin | HLA-B*15:02 | Candidates for treatment with carbamazepine and at risk of a serious adverse event: 1) Asian ancestry; 2) personal or family history of skin toxicity induced by other drugs; 3) previous severe cutaneous adverse reaction induced by phenytoin |

| Oxcarbazepine | HLA-B*15:02 | Candidates for treatment with carbamazepine and at risk of a serious adverse event: 1) Asian ancestry; 2) personal or family history of skin toxicity induced by other drugs; 3) previous severe cutaneous adverse reaction induced by oxcarbazepine |

| Siponimod | CYP2C9 | Candidates for treatment with siponimod (testing required per SmPC) |

| Clopidogrel | CYP2C19 | Limited to suspected nonresponse to treatment and/or suspected serious adverse event |

| Statins | SLCO1B1 | Previous serious adverse drug reaction (rhabdomyolysis) to simvastatin |

| Ivacaftor | CFTR | Candidates for treatment with ivacaftor (testing required per SmPC) |

| Allopurinol | HLA-B*58:01 | Candidates for treatment with allopurinol and at risk of a serious adverse drug reaction, especially patients of African or Asian ancestry |

| Proton pump inhibitors | CYP2C19 | In the context of treatment of Helicobacter pylori, limited to cases of failure of second-line treatment and treatments following omeprazole |

| Eliglustat | CYP2D6 | Candidates for treatment with eliglustat (testing required per SmPC) |

| Pimozide | CYP2D6 | Candidates for treatment with pimozide |

| Tetrabenazine | CYP2D6 | Candidates for treatment with tetrabenazine |

| Rasburicase | G6PD | Candidates for treatment with rasburicase and at high risk of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency(testing required per SmPC) |

For the purpose of this review, we summarized the information contained in the AEMPS database as well as the indications authorized in the pediatric population and some of the frequent off-label uses of the included active ingredients (information obtained from SmPCs4 in addition to consultation of the Pediamecum database of active ingredients authorized for use in pediatrics)5 (Table 2). Based on the results of this analysis, there are recommendations for 78 gene-drug pairs, of which nearly 80% (62) correspond to biomarkers included in the nationwide testing portfolio, and another 13% (10) have been proposed for inclusion in it. On the other hand, focusing on the 68 active ingredients in this database, 65% (44) have one or more pediatric indications, and the vast majority are used off-label in this age group.

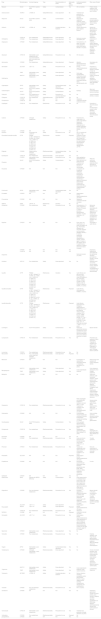

Drugs whose summary of product characteristics includes pharmacogenetic information according to the AEMPS and their use in pediatric care.

| Drug | Biomarker/gene | Involved subgroup | Type | Recommendations in SmPC | Nationwide NHS portfolio | Authorized pediatric indications | Other uses (off-label) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abacavir | HLA-B | HLA-B*57:01 positive allele | Safety | Contraindication | Yes | HIV (>3 months) | Preterm infants, newborns, and infants aged less than 3 months |

| Acenocoumarol | VKORC1 | c.1639G >A | Safety/effectiveness | Dose adjustment | No | Treatment and prevention of thromboembolic disorders | |

| Allopurinol | HLA-B | HLA-B*58:01 positive allele | Safety | Contraindication | Yes | Malignancies (especially leukemia), inborn errors of metabolism (eg, Lesch-Nyhan syndrome) | Leishmaniasis, prenatal asphyxia, hyperuricemia in chronic kidney disease |

| Amikacin | MT-RNR1 | c.1555A >G | Safety | Consider alternative treatment | No | Severe infections by gram-negative bacteria | Infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis in HIV-positive patient, other mycobacterial infections |

| Amitriptyline | CYP2C19 | Poor metabolizers | Safety/effectiveness | Dose adjustment | Yes | Nocturnal enuresis, neuropathic pain | Depression, prophylaxis of migraine |

| CYP2D6 | Poor metabolizers | Safety/effectiveness | Dose adjustment | Yes | |||

| Aripiprazole | CYP2D6 | Poor metabolizers | Safety/effectiveness | Dose adjustment | Yes | Schizophrenia (>15 years, oral route), manic episode in patient with bipolar disorder (>13 years) | Irritability in autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, tics in Tourette syndrome, irritability in Asperger syndrome |

| Atazanavir | CYP2C19 | Intermediate or poor metabolizers with concurrent treatment with voriconazole and ritonavir | Safety/effectiveness | Precautions for use | Yes | HIV (≥6 years) | |

| Atomoxetine | CYP2D6 | Poor metabolizers | Safety/effectiveness | Dose adjustment | Proposed | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (≥6 years) | Narcolepsy with cataplexy |

| Atorvastatin | SLCO1B1 | c.521T >C | Safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Primary hypercholesterolemia (>10 years) | Prevention of cardiovascular disease in children at high risk |

| Azathioprine | TPMT | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | Solid organ transplantation, inflammatory bowel disease, and other immune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, dermatomyositis, etc) | Myasthenia gravis, polyarteritis nodosa, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, autoimmune thrombocytopenia, atopic dermatitis, or uveitis |

| NUDT15 | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | |||

| Capecitabine | DPYD | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Safety | Contraindication/dose adjustment | Yes | No | |

| Carbamazepine | HLA-A | HLA-A*31:01 positive allele | Safety | Contraindication | Yes | Epilepsy | Mood and conduct/disruptive behavior disorders |

| HLA-B | HLA-B*15:02 positive allele | Safety | Contraindication | Yes | |||

| Celecoxib | CYP2C9 | Poor metabolizers or CYP2C9*3 carriers | Safety | Precautions for use/dose adjustment | Yes | No | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (≥ 2 years) |

| Citalopram | CYP2C19 | Poor metabolizers | Safety/effectiveness | Dose adjustment | Yes | No | |

| Clomipramine | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Obsessive-compulsive disorder, nocturnal enuresis | |

| CYP2C19 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | |||

| Clopidogrel | CYP2C19 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness | Precautions for use | Yes | No | Prevention of atherothrombotic and thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation. Secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. |

| Codeine | CYP2D6 | Ultrarapid metabolizers | Safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Nonproductive cough, pain (>12 years of age without respiratory impairment). Restricted use in pediatric population (source: MUH [FV], 3/2015) | |

| Doxepin | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | No | |

| Efavirenz | CYP2B6 | Homozygous for c.516G >T | Safety | Precautions for use | No | HIV (>3 months and weight > 3 kg) | |

| Elexacaftor/lumacaftor/ivacaftor | CFTR | F508del (c.1521_1523delCTT), (c.350G >A), (c.532G >A), (c.1645A >C), (c.1646G >A), (c.1651G >A), (c.1652G >A), (c.3731G >A), (c.4046G >A), (c.3752G >A), (c.3763T >C) | Effectiveness | Indication | Proposed | Treatment of cystic fibrosis (> 6 years) with at least one F508del mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR) | |

| Eliglustat | CYP2D6 | Indeterminate or ultrarapid metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Contraindication/dose adjustment | Yes | No | |

| Escitalopram | CYP2C19 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | No | |

| Phenytoin | CYP2C9 | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Status epilepticus, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and partial seizures. Treatment and prevention of seizures in neurosurgery. | Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, especially those secondary to digoxin toxicity |

| HLA-B | HLA-B*15:02 positive allele | Safety | Contraindication | Yes | |||

| Flecainide | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | (>12 years) Life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Prevention of symptomatic supraventricular arrhythmias in absence of structural heart disease. Patients with supraventricular tachycardia without underlying heart disease. | |

| Fluorouracil | DPYD | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Safety | Contraindication/dose adjustment | Yes | No | |

| Fluvastatin | CYP2C9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (>9 years) | |

| Fluvoxamine | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Obsessive-compulsive disorder (>8 years) | |

| Gefitinib | EGFR | c.2573T >G | Effectiveness | Indication | No | No | |

| Haloperidol | CYP2D6 | Poor metabolizers | Safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Schizophrenia (> 13 years). Aggressive behavior (>6 years) in autism or pervasive developmental disorders. Tourette syndrome (> 10 years). | Behavioral disorders associated with refractory aggression and hyperactivity, nausea and vomiting that do not respond to treatment or in palliative care patients |

| Ibuprofen | CYP2C9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Fever, pain, and inflammation (>6 years and weight >20 kg), inflammatory diseases, and rheumatic diseases such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (> 6 months), ankylosing spondylitis, osteoarthritis, or arthritis. Children aged ≥ 12 years or with weight ≥40 kg. IV: patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants born before 34 weeks. | Pancreatitis in cystic fibrosis |

| Imipramine | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Nocturnal enuresis (>5 years) | Depression, hyperactivity associated with tics, behavioral disorders, pain/adjuvant therapy in cancer treatment |

| CYP2C19 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | |||

| Irinotecan | UGT1A1 | Poor metabolizers | Safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | No | Refractory solid and central nervous system tumors, relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma (in combination with temozolomide) |

| Ivacaftor | CFTR | F508del (c.1521_1523delCTT), (c.350G >A), (c.532G >A), (c.1645A >C), (c.1646G >A), (c.1651G >A), (c.1652G >A), (c.3731G >A), (c.4046G >A), (c.3752G >A), (c.3763T >C) | Effectiveness | Indication | Yes | Cystic fibrosis and with one of the following gating (class III) mutations in the CFTR gene: G551D, G1244E, G1349D, G178R, G551S, S1251 N, S1255 P, S549 N or S549R (> 6 months) | |

| Ivacaftor/lumacaftor | CFTR | F508del (c.1521_1523delCTT), (c.350G >A), (c.532G >A), (c.1645A >C), (c.1646G >A), (c.1651G >A), (c.1652G >A), (c.3731 G >A), (c.4046G >A), (c.3752G >A), (c.3763T >C) | Effectiveness | Indication | Proposed | Cystic fibrosis, homozygous for F508del (> 6 years) | |

| Ivacaftor/tezacaftor | CFTR | F508del (c.1521_1523delCTT), (c.350G >A), (c.532G >A), (c.1645A >C), (c.1646G >A), (c.1651G >A), (c.1652G >A), (c.3731G >A), (c.4046G >A), (c.3752G >A), (c.3763T >C) | Effectiveness | Indication | Proposed | Cystic fibrosis: homozygous for F508del or heterozygous for F508del with one of the following residual-function mutations: P67L, R117C, L206W, R352Q, A455E, D579G, 711 + 3A → G, S945L, S977F, R1070W, D1152H, 2789 + 5G → A, 3272-26A→G y 3849 + 10kbC → T (≥ 12 years) | |

| Lamotrigine | HLA-B | HLA-B*15:02 positive | Safety | Contraindication | Yes | Partial and generalized seizures, including tonic-clonic seizures (≥13 years). Seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (>2 years) | Bipolar disorder |

| Lansoprazole | CYP2C19 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | No | Prevention and treatment of reflux esophagitis. Treatment of duodenal and gastric ulcers. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome |

| Lornoxicam | CYP2C9 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | No | |

| Mavacamten | CYP2C19 | Poor, intermediate, normal, rapid and ultrarapid metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Dose adjustment | Proposed | No | |

| Meloxicam | CYP2C9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Exacerbations of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis (>16 years) | Relief of signs and symptoms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis |

| Mercaptopurine | NUDT15 | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Crohn disease in adolescents. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

| TPMT | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | |||

| Metoprolol | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | No | High blood pressure, acute myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and supraventricular tachycardia. Migraine prophylaxis. Congestive heart failure. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, control of aortic disease in Marfan syndrome, long QT syndrome |

| Omeprazole | CYP2C19 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Reflux esophagitis and symptomatic treatment of heartburn and acid reflux (>1 year) | Severe erosive esophagitis, gastric ulcers, gastric hypersecretion, stress ulcer prophylaxis, IV route |

| Treatment of duodenal ulcer caused by Helicobacter pylori (>4 years) | |||||||

| Ondansetron | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (≥6 months) Postoperative nausea and vomiting (>1 month) | Cyclic vomiting syndrome, recurrent vomiting associated with acute gastroenteritis |

| Oxcarbazepine | HLA-B | HLA-B*15:02 positive allele | Safety | Contraindication | Yes | Partial epileptic seizures with or without secondary generalization (≥6 years) | |

| Pantoprazole | CYP2C19 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (≥12 years) | Erosive esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease (≥5 years) |

| Paroxetine | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | No | |

| Pimozide | CYP2D6 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Acute and chronic psychosis and anxiety disorders (very limited evidence in >3 years) | Tourette syndrome |

| Piroxicam | CYP2C9 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Topical and symptomatic local relief of painful or inflammatory conditions (>12 years) | Pain and inflammation in inflammatory and rheumatic diseases |

| Pitavastatin | SLCO1B1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Proposed | Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (>6 years) | |

| Propafenone | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (atrial fibrillation, paroxysmal atrial flutter, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome), ventricular arrhythmias | IV route |

| Quetiapine | CYP3A4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | No | |

| Rasburicase | G6PD | Patients with G6PDH deficiency | Safety | Contraindication | Yes | Acute hyperuricemia in malignant blood tumors with a high tumor burden and risk of rapid tumor lysis syndrome or rapid tumor reduction at the start of chemotherapy | |

| Risperidone | CYP2D6 | Poor and ultrarapid metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Persistent aggression in behavioral disorders in children with below-average intellectual functioning or with diagnosed intellectual disability (>5 years) | Bipolar disorder (>10 years), schizophrenia (>13 years), Tourette syndrome, behavioral changes in autism spectrum disorders (>5 years) |

| Rosuvastatin | SLCO1B1 | c.521T > C | Safety | Dose adjustment | Proposed | Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (>6 years) | |

| ABCG2 | c.421C >A | Safety | Dose adjustment | ||||

| Sertraline | CYP2C19 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Obsessive-compulsive disorder (>6 years) | |

| CYP2B6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Proposed | |||

| Simvastatin | SLCO1B1 | c.521 T >C | Safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (male adolescents in Tanner stage II or above of pubertal development, and female adolescents at least one year after menarche, aged 10 to 17 years) | |

| Siponimod | CYP2C9 | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | No | |

| Tamoxifen | CYP2D6 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | No | Pubertal, idiopathic, and drug-induced gynecomastia. Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (McCune-Albright syndrome). Retinoblastoma |

| Tegafur | DPYD | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Safety | Contraindication/dose adjustment | Yes | No | |

| Tetrabenazine | CYP2D6 | Ultrarapid, intermediate, or poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | No | Choreic movement disorders, post-hypoxic chorea, postencephalitic hyperkinesia, Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, Tourette syndrome, generalized dystonia, dystonic cerebral palsy |

| Tioguanine | NUDT15 | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Acute myeloid leukemia. | Lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| TPMT | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Safety | Dose adjustment | Yes | |||

| Tobramycin | MT-RNR1 | c.1555A >G | Safety | Consider alternative treatment | No | Serious infections caused by susceptible aerobic gram-positive bacteria or gram-negative bacilli, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and enterobacteria | |

| Tramadol | CYP2D6 | Poor and ultrarapid metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Pain (>3 years) | |

| Venlafaxine | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | No | Depression, generalized anxiety and social phobia, panic disorder, cataplexy and other abnormal manifestations of REM sleep. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. |

| Voriconazole | CYP2C19 | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Yes | Treatment and prevention of fungal infections (≥2 years) | |

| Vortioxetine | CYP2D6 | Poor metabolizers | Effectiveness/safety | Precautions for use | Proposed | No | |

| Zuclopenthixol | CYP2D6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | No |

Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

The table shows whether the drug is authorized for any pediatric indication, and whether the SmPC includes recommendations for dose adjustment or, otherwise, precautions or use based on the pharmacogenomic results.

Of the 19 drugs specifically included in the nationwide catalog, 13 (68%) have authorized pediatric indications: the anti-infectives abacavir, atazanavir, and voriconazole; the anticonvulsants carbamazepine, phenytoin, and oxcarbazepine; the thiopurines (azathioprine and mercaptopurine); omeprazole; ivacaftor; allopurinol; pimozide; and rasburicase. In the case of abacavir, atazanavir combined with voriconazole and ritonavir, ivacaftor, and rasburicase, testing is required prior to treatment, as it determines the indication of the drug (ivacaftor) or a clear contraindication for its use (all others). However, for the rest of the drugs included in the nationwide catalog and most of the drugs in the AEMPS database, the SmPC does not specify whether testing should be performed nor include specific recommendations for dose adjustment. That is why the main scientific societies and expert working groups in pharmacogenetics develop guidelines and consensus recommendations based on the current evidence. These guidelines are essential to guide the implementation of pharmacogenetics in clinical practice.

Pediatric information in pharmacogenetic guidelinesAt present, the CPIC is the pharmacogenetics association with the greatest number of guidelines for dosage adjustment. The article describing its guideline development process specifies that each recommendation includes an assessment of its usefulness in pediatric patients.6 At the time of this writing, the CPIC has published a total of 27 guidelines, of which 24 include at least one section with recommendations adapted to the pediatric population (Table 3). Specifically, there are four drugs for which there are specific dosing recommendations for children: atomoxetine, efavirenz, voriconazole and warfarin. In the rest of the CPIC guidelines, recommendations based on the genotype and phenotype are extrapolated from the adult population, with certain limitations due to the scarcity of the evidence or the immaturity of drug metabolizing pathways in young children.2

Drugs used in the pediatric population for which a Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium guideline is available.

| CPIC | Gene | Type | Pediatric recommendation in guideline | Specific pediatric recommendation | Summary of recommendation | Date of initial publication | Date of last update |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abacavir43 | HLA-B | Safety | No | No | Contraindicated in HLA-B*57:01 carriers | Apr-12 | May-14 |

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | |||||||

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs44 (celecoxib, ibuprofen, flurbiprofen, lornoxicam and meloxicam) | CYP2C9 | Safety | Yes (adolescents) | No | CYP2C9 IM (activity = 1): start treatment at minimum effective dose | Mar-20 | Mar-20 |

| CYP2C9 PM: start treatment at 25%-50% of minimum effective dose. If titration is necessary, wait until steady state is achieved | |||||||

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation. Enzyme activity maturity from 3 years | Meloxicam: | ||||||

| CYP2C9 IM (activity = 1): initiate treatment with 50% minimum effective dose | |||||||

| CYP2C9 PM: consider alternative NSAID that is not metabolized via CYP2C9 or has a shorter half-life | |||||||

| Allopurinol45 | HLA-B | Safety | No | No | Contraindicated in HLA-B*58:01 carriers | Feb-13 | Jun-15 |

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | |||||||

| Aminoglycosides28 | MT-RNR1 | Safety | Yes | No | Contraindicated in carriers of risk variants in MT-RNR1 gene (m.1095T >C; m.1494C >T; m.1555A >G) | May-21 | May-21 |

| Recommendations independent of patient age, applicable to adult and pediatric patients from birth | |||||||

| Inhalational anesthetics | RYR1 | Safety | Yes | No | Contraindicated in patients carrying risk variants of RYR1 and CACNA1S genes | Sep-19 | Dec-23 |

| Succinylcholine46 | CACNA1S | ||||||

| SSRI antidepressants38 | CYP2D6 | Efficacy and safety | Yes (children and adolescents) | No | Citalopram and escitalopram: | Apr-23 | Apr-23 |

| CYP2C19 | CYP2C19 UM and PM: contemplate the use of another SSRI not metabolized via CYP2C19 | ||||||

| CYP2B6 | RM: if the desired effect is not achieved with the standard dose, contemplate the use of another SSRI not metabolized via CYP2C19 | ||||||

| SLC6S4 | Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | IM: initiate standard dose with slower titration | |||||

| HTR2A | Sertraline: | ||||||

| CYP2C19 IM: slower titration, consider lower maintenance dose | |||||||

| CYP2C19 PM: initial dose smaller than standard starting dose, slower titration consider 50% reduction of maintenance dose or alternative treatment | |||||||

| CYP2B6 IM: slower titration, consider reduced maintenance dose | |||||||

| CYP2B6 PM: initial dose lower than standard starting dose, slower titration, consider 25% reduction in maintenance dose or alternative treatment | |||||||

| Tricyclic antidepressants41 | CYP2D6 | Efficacy and safety | Yes (children and adolescents) | No | CYP2C19 UM, RM and PM: avoid use, consider alternative drug not metabolized via CYP2C19 | May-13 | Oct-19 |

| CYP2D6 UM and PM: avoid use, consider alternative drug not metabolized by CYP2D6 | |||||||

| CYP2C19 | Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | CYP2D6 IM: reduce dose by 25% | |||||

| Atazanavir48 | UGT1A1 | Safety | Yes | No | UGT1A1 PM: consider alternative treatment due to high probability of developing jaundice | Sep-15 | Nov-17 |

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | |||||||

| Atomoxetine49 | CYP2D6 | Efficacy and safety | Yes | Yes | CYP2D6 UM and NM (activity score ≥ 1): dose may be increased after 3 days of treatment | Feb-19 | Oct-19 |

| CYP2D6 PM: initiate standard starting dose with increase from day 14 if necessary | |||||||

| Beta-blockers42 (metoprolol) | CYP2D6 | Safety | Yes | No | CYP2D6 PM: initiation at minimum effective dose with slow titration. In the case of adverse events, consider a different beta-blocker | Jul-24 | Jul-24 |

| ADRB1 | |||||||

| ADRB2 | |||||||

| ADRA2C | Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | ||||||

| GRK4 | |||||||

| GRK5 | |||||||

| Carbamazepine | HLA-A | Safety | Yes | No | Drugs contraindicated in HLA-B*15:02 and HLA-A*31:01 carriers | Sep-13 | Dec-17 |

| Oxcarbazepine50 | HLA-B | Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | |||||

| Clopidogrel51 | CYP2C19 | Efficacy | Yes | No | CYP2C19 IM and PM: avoid use of clopidogrel, consider treatment with alternative antiplatelet medication | Aug-11 | Jan-22 |

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | |||||||

| Efavirenz36 | CYP2B6 | Safety | Yes | Yes | Patients aged ≥ 3 months and < 3 years. | Apr-19 | Apr-19 |

| CYP2B6 PM: reduce dose based on patient weight | |||||||

| 5 to < 7 kg: 50 mg | |||||||

| 7 to < 14 kg: 100 mg | |||||||

| 14 to < 17 kg: 150 mg | |||||||

| ≥ 17 kg: 150 mg Patients > 3 years with weight < 40 kg: no dosing recommendations based on pharmacogenetic profile. | |||||||

| Patients weighing ≥ 40 kg: | |||||||

| CYP2B6 IM: consider starting daily dose of 400 mg | |||||||

| CYP2B6 PM: consider starting daily dose of 400-200 mg | |||||||

| Statins52 | SLCO1B1 | Safety | Yes | No | All statins: | Jan-22 | Jan-22 |

| SLCO1B1 intermediate and poor function: specific recommendation for each indication and statin | |||||||

| ABCG2 | Rosuvastatin: | ||||||

| ABCG2 poor function: consider doses no greater than 20 mg or alternative treatment options | |||||||

| CYP2C9 | Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | Fluvastatin: | |||||

| CYP2C9 IM: avoid doses greater than 40 mg or consider alternative treatment options | |||||||

| CYP2C9 PM: avoid doses greater than 20 mg or consider alternative treatment options | |||||||

| Phenytoin53 | HLA-B | Safety | Yes (recommendation based on CYP2C9 in children aged > 2 years) | No | Contraindicated in HLA-B*15:02 carriers | Nov-14 | Aug-20 |

| In patients who do not carry HLA-B*15:02: | |||||||

| CYP2C9 | Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | CYP2C9 IM (activity score = 1): consider 25% reduction in initial dose + therapeutic drug monitoring | |||||

| CYP2C9 PM (activity score = 0): consider 50% reduction in initial dose + therapeutic drug monitoring | |||||||

| Fluoropyrimidines54 | DPYD | Safety | Yes | No | DPYD IM (activity score 1.5): consider 25% reduction in starting dose | Dec-13 | Oct-17 |

| DPYD IM (activity score 1): consider reducing starting dose by 25% | |||||||

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | DPYD PM (activity score 0-0,5): avoid the use of fluoropyrimidines | ||||||

| Proton pump inhibitors13 | CYP2C19 | Efficacy and safety | Yes (>1 year) | No | CYP2C19 UM: Increase starting daily dose by 100%. (Daily dose may be given in divided doses) | Aug-20 | Aug-20 |

| CYP2C19 NM and RM: consider increasing dose by 50%-100% for the treatment of erosive esophagitis and duodenal ulcer caused by Helicobacter pylori infection | |||||||

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | CYP2C19 IM and PM: for chronic therapy lasting more than 12 weeks, consider 50% reduction in daily dose | ||||||

| Ivacaftor55 | CFTR | Efficacy | Yes (>6 years) | No | Use in patients carrying described G551D-CFTR variants | Mar-14 | May-19 |

| Ondansetron | CYP2D6 | Efficacy | Yes (>1 month) | No | CYP2D6 PM: consider alternative antiemetic not chiefly metabolized via CYP2D6 | Dec-16 | Oct-19 |

| Tropisetron56 | Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | ||||||

| Opioids57 (codeine and tramadol) | CYP2D6 | Efficacy and safety | Yes (>12 years) | No | CYP2D6 UM and PM: avoid use of codeine and tramadol | Feb-12 | Dec-20 |

| OPRM1 | |||||||

| COMT | Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | ||||||

| Pegylated interferon alfa58 | IFNL3 | Efficacy | No | No | Patients with CT or TT genotype (rs12979860 variant) do not respond well to ribavirin + PEG-IFN-α-based regimens | Feb-14 | Feb-14 |

| Tacrolimus22 | CYP3A5 | Efficacy | Yes | No | CYP3A5 NM and IM: Increase starting dose 1.5-2 times + therapeutic drug monitoring | Jul-15 | Jul-15 |

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | |||||||

| Tamoxifen59 | CYP2D6 | Efficacy | No | No | CYP2D6 IM and PM: consider alternative treatment; if not possible, consider dose increase | Jan-18 | Jan-18 |

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | |||||||

| Thiopurines31 (tioguanine, mercaptopurine, azathioprine) | TPMT | Safety | Yes | No | TPMT IM: start with reduced starting doses (30%–80% of normal dose) | Mar-11 | Nov-18 |

| TPMT PM: start with drastically reduced doses (based on drug/indication). Azathioprine: For nonmalignant conditions, consider alternative nonthiopurine immunosuppressant therapy | |||||||

| NUDT15 | Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | NUDT15 IM: Start with reduced starting doses (30–80% of normal dose) | |||||

| NUDT15 PM: start with drastically reduced doses (based on drug/indication). Azathioprine: For nonmalignant conditions, consider alternative nonthiopurine immunosuppressant therapy | |||||||

| Various drugs60 | G6PD | Safety | Yes | No | G6PD deficiency: avoid contraindicated drugs | Aug-14 | Aug-22 |

| Pediatric extrapolation of adult recommendation | |||||||

| Voriconazole21 | CYP2C19 | Efficacy and safety | Yes | Yes | CYP2C19 UM: consider use of an alternative antifungal agent | Dec-16 | Dec-16 |

| CYP2C19 RM, NM, IM: initiation with standard dose and therapeutic drug monitoring | |||||||

| CYP2C19 PM: consider use of an alternative antifungal if reducing the initial dose is not an option | |||||||

| Warfarin61 | CYP2C9 | Safety | Yes | Yes | For patients of European ancestry with CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3 or/and VKORC1-1639 genotypes, use validated algorithm | Oct-11 | Dec-16 |

| VKORC1 | |||||||

| CYP4F2 |

Abbreviations: CPIC, Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium; IM, intermediate metabolizer; NM, normal metabolizer; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PM, poor metabolizer; RM, rapid metabolizer; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; UM, ultrarapid metabolizer.

The additional references for Table 3 can be found in Appendix B.

Guidelines and consensus documents published by other groups and organizations, such as the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group and the Spanish Society of Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics do not systematically include an assessment of the usefulness in the pediatric population. At present, they only include specific pediatric dosing information for atomoxetine due to the specific use of this drug in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.7,8

Recommendations for drugs commonly used in pediatric careWe now proceed to a more detailed description of the drug-gene pairs for which CPIC guidelines are available and which are considered most relevant in pediatrics based on the current evidence and the frequent use of the corresponding drug in the pediatric population, following consultation with a group of experts that included pediatricians and hospital-based pediatric pharmacists.

Proton pump inhibitors-CYP2C19 geneProton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are frequently used in the pediatric population for conditions such as reflux esophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and duodenal ulcer caused by Helicobacter pylori. In addition, its use is increasingly widespread in this population for other indications that are not authorized in the SmPC.9 Most PPIs are mainly metabolized by CYP2C19.4 The activity of CYP2C19 is very low in the early months of life, so the clearance of PPIs in preterm infants and term infants aged less than 2 or 3 months is lower compared to the adult population.10 In children aged more than 1 year, there is growing evidence that certain CYP2C19 variants affect the pharmacokinetics and response to PPIs,11,12 as is the case in the adult population. The CYP2C19 ultrarapid metabolizer (UM) and rapid metabolizer (RM) phenotypes are associated with lower plasma concentrations and a poorer response to treatment compared to the normal metabolizer (NM) phenotype. On the other hand, the poor metabolizer (PM) phenotype is associated with higher plasma concentrations compared the NM phenotype, in addition to an increased risk of drug toxicity. It is recommended that treatment be optimized based on the pharmacogenetic profile in patients aged more than 1 year, increasing the dose for treating ulcers in UMs and RMs, and considering a reduction in prolonged regimens for PMs from age 2 to 3 months13 (Table 3).

Abacavir, allopurinol, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine and phenytoin-HLA-A and HLA-B genesHLA-A and HLA-B are genes that are part of the human major histocompatibility complex (human leukocyte antigen [HLA]) of the immune system and are highly polymorphic due to the need to present a broad range of peptides for immune recognition.14 Some alleles of these genes have been associated with T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity reactions and serious adverse skin reactions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis following administration of certain drugs, especially in certain ethnic groups.15,16 Among them, the HLA-B*57:01 allele is associated with hypersensitivity reactions following administration of abacavir, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, so testing of all candidates for treatment with this drug is recommended before treatment initiation, in addition to the use of alternative drugs if the test is positive.

Other examples of HLA risk alleles include HLA-B*58:01 (associated with allopurinol-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in Han Chinese, Malays, Thais, Europeans, and Koreans), HLA-B*15:02 (phenytoin-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in Han Chinese and Thais), and HLAB*15:02 (toxicity induced by carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine in Han Chinese, Thais, Koreans, and Malays). In addition, the HLA-A*31:01 allele may increase the risk of carbamazepine-induced skin reactions, with a stronger association in the European and Japanese populations. In all these cases, the presence of one or two copies of the risk allele is a contraindication for the drug, and testing is recommended in subgroups of patients considered at risk, as well as in patients with a family history of hypersensitivity reactions associated with these drugs. All available guidelines extrapolate the adult recommendation to the pediatric population on the basis that this risk association is independent of age, with the exception of phenytoin, for which there is mention that the information is derived from studies that included children.

In the case of phenytoin, the guideline also includes dose adjustment recommendations based on the CYP2C9 phenotype assignment, as this is the enzyme chiefly responsible for metabolizing this drug. Since CYP2C9 activity in children approximates adult levels starting from age 5 months to 2 years, it is recommended that dose adjustments be applied from age 2 years.17 However, one of the most common uses of phenytoin in the pediatric population is the management of neonatal seizures, and the genotype-enzyme activity correlation is not well established in the neonatal population, so the practical utility of testing is limited in this case.

Voriconazol-CYP2C19Voriconazole is a broad-spectrum triazole antifungal agent indicated in adults and children aged 2 years and older for the treatment and prophylaxis of fungal infections.18

Its metabolism is complex and depends mainly on the CYP3A4, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9 enzymes, which metabolize approximately 70% to 75% of the drug, while the remaining 25% to 30% is metabolized by enzymes from the flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO) family.4 Although the expression of CYP2C19 and FMO3 is similar in children and adults, their contribution to the clearance of voriconazole seems to be higher in children, while CYP3A4 would play a larger role in adults.19

Different studies suggest that CYP2C19 variants account for 50% to 55% of the variation in voriconazole metabolism.20 The presence of these variants may give rise to the phenotypes mentioned above (UM, RM, intermediate metabolizer [IM], PM), which have an impact on voriconazole exposure.

In the pediatric age group, PMs and IMs exhibit higher plasma concentrations of voriconazole compared to NMs, while RMs do not have significantly different concentrations compared to NMs. In contrast, UMs have decreased voriconazole concentrations. There is evidence that voriconazole exposure is greater in IM or PMs, which may require dose adjustments to minimize the risk of toxicity. It is important to monitor concentrations in these patients and adjust the dose as needed.21

Dosing recommendations for children and adolescents are extrapolated from adults, except for RMs, for whom it is recommended to initiate treatment with the standard dose and monitor plasma concentrations.

Tacrolimus-CYP3A5Tacrolimus is an immunosuppressant in the calcineurin inhibitor group widely used in pediatrics, chiefly for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in solid-organ transplant recipients (kidney, liver, heart).5

Tacrolimus is largely metabolized in the liver and the intestinal wall by CYP3A5 and CYP3A4. CYP3A5 variants may affect the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus, explaining 50% of interindividual variability.22 Nearly 80% of individuals of European ancestry are PMs, so they require lower doses than NMs or IMs. For this reason, the standard dose of tacrolimus is adjusted for PMs.

The effect of the CYP3A5 genotype in the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in pediatric populations has been studied in different clinical contexts,23 and most studies have been conducted in kidney transplant recipients.24,25 In patients with NM (CYP3A5*1/*1) or IM (CYP3A5*1/*3) phenotypes, tacrolimus trough concentrations tend to be 1.5 to 2 times lower compared to PMs starting from the first weeks of treatment to up to one year post transplantation.25–27 This has led to recommendation of a higher initial dose compared to the dose recommended for PMs.

It should be noted that other factors, such as age or concomitant treatment, may contribute to the interindividual variability in tacrolimus exposure in children. Regardless of the genotype, therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended to ensure concentrations within the therapeutic range established for immunosuppression.

Aminoglycosides-MT-RNR1Aminoglycosides are authorized for pediatric use for treatment of serious infections caused by gram-negative bacteria. These drugs have notable side effects, such as nephrotoxicity, vestibulotoxicity, and sensorineural hearing loss (cochleotoxicity)

MT-RNR1 is a gene that encodes the 12 s rRNA subunit and is the mitochondrial homologue of the prokaryotic 16S rRNA. Some MT-RNR1 variants (m.1095T >C; m.1494C >T; m.1555A >G) more closely resemble the bacterial 16 s rRNA subunit and result in increased risk of aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss. Therefore, use of aminoglycosides should be avoided in individuals with these MT-RNR1 variants, unless the high risk of permanent hearing loss is outweighed by the severity of infection and safe or effective alternative therapies are not available.28 The recommendations are independent of patient age and apply to adult and pediatric patients from birth.

Thiopurines (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, tioguanine)-TPMT, NUDT15Thiopurines (tioguanine, mercaptopurine and azathioprine) are drugs whose use in the pediatric population include treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and inflammatory bowel disease. Their toxicity profile includes gastrointestinal adverse events, myelosuppression and hepatotoxicity. The two latter are most concerning and are dose-dependent.29

Thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) and NUDIX hydrolase 15 (NUDT15) are essential enzymes in thiopurine metabolism. Thus, individuals with decreased TPMT or NUDT15 activity are at high risk of serious adverse events. There is evidence of a strong correlation between the TPMT and NUDT15 genotype and the metabolizer phenotype for these enzymes.30

None of the guidelines, save for the 2013 CPIC guideline, mentions the pediatric population in its recommendations.31 The CPIC guideline addresses dose adjustments in pediatric patients, in spite of the scarcity of data for this population. Thus, since the dosing recommendations for thiopurines in adults are given in relation to kilograms of body weight or body surface area, the guideline states that it can be assumed (as is actually done in practice) that the recommended dose adjustments can be extrapolated to children.

Atomoxetina-CYP2D6Atomoxetine is a potent and highly selective inhibitor of the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter used in children aged 6 years and older to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. It is also used off-label in narcolepsy with cataplexy.

Multiple factors affect the pharmacokinetics of atomoxetine. It is predominantly metabolized by CYP2D6 and, to a much lesser extent, CYP2C19.32 Plasma concentrations of atomoxetine in PMs have been found to be up to eight-fold higher compared to NMs.33 This is consistent with the increased incidence of adverse events in PMs compared to RMs in the pediatric population, especially decreased appetite, combined insomnia and combined depression.34

In pediatric CYP2D6 PMs, a lower starting dose is recommended, along with a slower escalation or even no escalation if the desired therapeutic effect is achieved. The combination of genotyping and therapeutic drug monitoring, if available, is the best approach to ensure safe use.35 If monitoring is not possible, caution is particularly recommended in the case of concurrent treatment with CYP2D6 inhibitors (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, quinidine, terbinafine), as they can increase plasma concentrations of atomoxetine.

Recommendations for other drugs used less frequently in pediatricsEfavirenz is a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. It is used to treat human immunodeficiency virus in combination with other drugs in children aged 3 months or older and weighing more than 3 kg. At present, its use in pediatric patients is limited, as there are alternatives with better tolerability. The SmPC notes that patients homozygous for the G516 T CYP2B6 variant may have higher plasma concentrations of efavirenz. The guideline provides dosing recommendations based on the CYP2B6 phenotype and the age and weight of the patient.36

In the case of drugs such as clopidogrel, ondansetron, tricyclic antidepressants, or serotonin reuptake inhibitors, the use of clinical guidelines for dose adjustment is well established in the adult population, but there are few specific pharmacogenetic studies (usually small) on which to base specific recommendations for the pediatric and adolescent population. In addition, the frequent off-label use of these drugs further hinders the availability of evidence specific for these diseases. In most cases, the guidelines mention the possibility of extrapolating adult recommendations based on the pharmacokinetics of drug-gene interaction and the maturation of the involved enzymatic pathways, if use of these drugs is necessary.

The only guidelines that refer to specific recommendations for the pediatric and adolescent populations are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and the recently published beta-blocker guidelines.

In the case of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, the guideline indicates that citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline are the drugs for which the most pharmacogenetic data are available to support gene-based prescribing in pediatric and adolescent populations, although these data are mainly derived from small pharmacokinetic studies.37,38

In respect of amitriptyline, the guideline notes that due to the lower dosage used for treatment of neuropathic pain in pediatric patients (eg, 0.1 mg/kg/day) it is less likely that PMs and IMs will experience adverse effects due to supratherapeutic plasma concentrations of amitriptyline, so dose adjustments are only recommended for indications requiring higher doses.

The beta-blocker guideline mentions two pharmacogenetic studies in the pediatric population, one on the association of ADRB1 and CYP2C9 variants with the efficacy of atenolol and losartan in Marfan syndrome, and another on the impact of CYP2D6 polymorphisms on the efficacy of propranolol for treatment of hemangioma.39,40 However, definite conclusions cannot be drawn based on the results of these studies. The guideline concludes that it may be appropriate, with caution, to extrapolate the recommendations given for the adult population to CYP2D6 and metoprolol (in PMs, initiation with a lower dose and slower progressive titration, watching for the potential development of bradycardia), since the CYP2D6 genotype seems to correlate to enzyme activity from 2 weeks post birth.

Other drugs such as statins, fluoropyrimidines, or tamoxifen are rarely used in the pediatric population, so there are no pharmacogenetic studies or specific recommendations for them. Pharmacogenetic tests are not routinely performed in the pediatric population, but it should be noted that as genotyping techniques advance, prospective testing with broad gene panels is becoming increasingly common. In such cases, the information will be available for future use and will be helpful if the use of these drugs is contemplated.

Implementation and limitationsIn the pediatric population, the problems generally encountered in the implementation of pharmacogenetics (lack of training for health care staff, lack of experts in pharmacogenetics, the dispersion of tests among different services, limited interest on the part of hospital administrators, etc) are exacerbated by the dearth of pediatric research establishing differential characteristics in reference to the population normally included in clinical trials and observational studies. Despite these difficulties, the update of the genomic service portfolio, with the inclusion of pharmacogenomics, is a clear boost to its implementation. The creation of multidisciplinary groups to engage in the implementation of pharmacogenetics in each hospital is key, as is the inclusion of pediatric specialists in these groups to ensure the rapid and safe application of pharmacogenetics in the pediatric population.

FundingThis research project did not receive specific financial support from funding agencies in the public, private or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.