Primary immunodeficiencies (PIDs) are diseases said to be “rare”. Although their individual prevalence is low, each year new genes are found that are associated with immunodeficiency. At present, there are 340 known defects, when in 2000 fewer than 100 had been identified.1 These diseases may be more prevalent than previously thought. It is estimated that 1 in 2000 individuals has a PID,1,2 a prevalence that is higher than that of leukaemia in the United States.2

Primary immunodeficiencies may have onset with recurrent infections in childhood, although at times they manifest as autoinflammation or autoimmunity.1,3 These less typical presentations may result in delay diagnosis, when early identification has an impact on outcomes, prevents morbidity and reduces mortality in PIDs requiring stem cell transplantation.3

In 2012, a specialised clinic was created within our department for follow-up of patients with confirmed PID and screening of patients with suspected PID. From its inception to 2017, the clinic has provided care for 135 children, 57% of who were referred in the past 2 years and 41% in 2017.

Of this total, 57% of patients have PID confirmed by the Department of Immunology of our hospital (77/135) and 15% are still under evaluation (21/135), while PID was ruled out in the remaining 27% (37/135). Of the children referred from other hospitals, 78% had a PID (25/32), as did 50% of children referred from other departments in our hospital (39/79) and 42% of children referred from primary care (8/19) (P=.009). The reason for referral was severe/recurrent infections in 51% (69/135), diagnosis of PID in 22% (30/135), lymphopaenia or hypogammaglobulinaemia in 19% (26/135), family history of PID in 6% (8/135) and delayed separation of the umbilical cord in 1.4% (2/135). Before referral, 20% were receiving antibiotic prophylaxis or immunoglobulin replacement therapy (28/135).

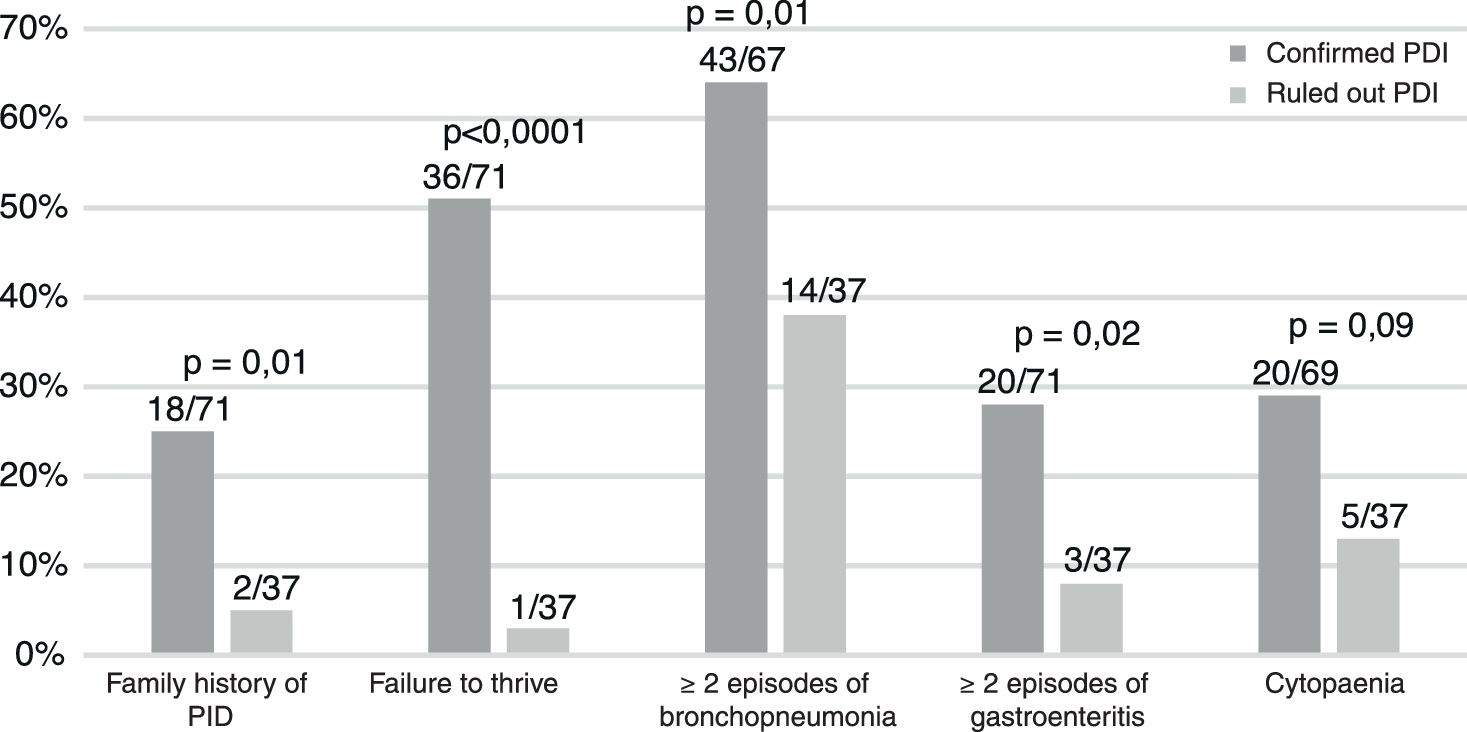

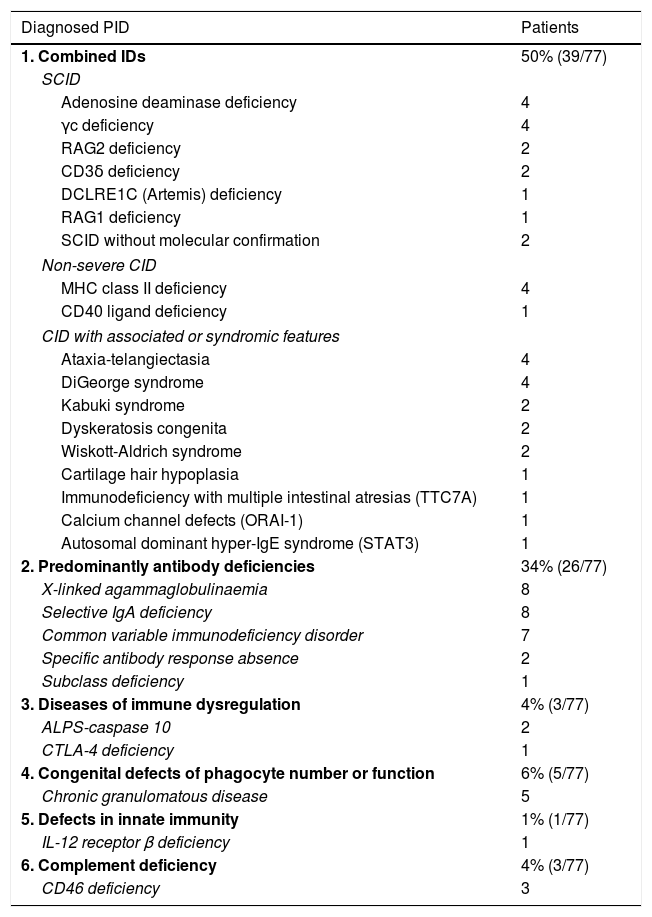

Table 1 summarises the diagnosed PIDs, and Fig. 1 the characteristics of the patients. A history of consanguinity was present in 9% of patients (6/71). All children with symptomatic infection by cytomegalovirus (n=6) had a PID.

Diagnosis in patients with PID managed in our clinic according to the most recent classification of the International Union of Immunological Societies.

| Diagnosed PID | Patients |

|---|---|

| 1. Combined IDs | 50% (39/77) |

| SCID | |

| Adenosine deaminase deficiency | 4 |

| γc deficiency | 4 |

| RAG2 deficiency | 2 |

| CD3δ deficiency | 2 |

| DCLRE1C (Artemis) deficiency | 1 |

| RAG1 deficiency | 1 |

| SCID without molecular confirmation | 2 |

| Non-severe CID | |

| MHC class II deficiency | 4 |

| CD40 ligand deficiency | 1 |

| CID with associated or syndromic features | |

| Ataxia-telangiectasia | 4 |

| DiGeorge syndrome | 4 |

| Kabuki syndrome | 2 |

| Dyskeratosis congenita | 2 |

| Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome | 2 |

| Cartilage hair hypoplasia | 1 |

| Immunodeficiency with multiple intestinal atresias (TTC7A) | 1 |

| Calcium channel defects (ORAI-1) | 1 |

| Autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome (STAT3) | 1 |

| 2. Predominantly antibody deficiencies | 34% (26/77) |

| X-linked agammaglobulinaemia | 8 |

| Selective IgA deficiency | 8 |

| Common variable immunodeficiency disorder | 7 |

| Specific antibody response absence | 2 |

| Subclass deficiency | 1 |

| 3. Diseases of immune dysregulation | 4% (3/77) |

| ALPS-caspase 10 | 2 |

| CTLA-4 deficiency | 1 |

| 4. Congenital defects of phagocyte number or function | 6% (5/77) |

| Chronic granulomatous disease | 5 |

| 5. Defects in innate immunity | 1% (1/77) |

| IL-12 receptor β deficiency | 1 |

| 6. Complement deficiency | 4% (3/77) |

| CD46 deficiency | 3 |

CID, combined immunodeficiency; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency.

Of all patients with PID, 34% required admission at the time of the first visit (26/75) compared to 11% of patients ultimately found to be healthy (4/37) (P=.006). Of the children with PID referred from a different hospital, 68% (17/25) were admitted at the time of the first visit, as were 18% (7/39) of those referred from another department in our hospital and 12% (1/8) of patients referred from primary care (P=.0001).

Fifty-seven percent of children with PID required immunoglobulin replacement therapy (42/74) and 41% antibiotic prophylaxis (31/75), while 36% underwent or require stem cell transplantation (28/77). The mortality in our study was of 13% (10/77).

Each passing day, we learn of additional genetic abnormalities associated with PIDs. These diseases carry a high morbidity and mortality, especially in cases of delayed diagnosis. Recurrent infection is a frequent reason for consultation and determining which patients require an immunologic evaluation is challenging. A history of consanguinity is a risk factor that should alert clinicians of the possibility of a PID. A recent case series of children with a history of recurrent infection found that 21% had a PID,4 a high prevalence that could be explained by the large proportion of consanguinity (38%).

However, infection is not always the initial presentation. In recent years, the classic signs used to detect PIDs have been questioned,5 as they cannot be used to identify patients with PID due to immune dysregulation, who have onset with autoimmunity or inflammation. Fischer et al. have reported that children with PID have a risk that is 830, 80 and 40 times greater of haemolytic anaemia, inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis, respectively, compared to the general paediatric population.6

The data suggest that failure to thrive, symptomatic cytomegalovirus infection and a family history of PID are relevant warning signs.3–5 Patients with more severe disease, referred from hospitals or requiring admission are also at higher risk.

We have recently observed an increase in the referral of patients, many with well-founded diagnostic suspicion and more than half with a final diagnosis of PID. This is due to the increasing number of cases diagnosed in the Department of Immunology of our hospital and the growing awareness of referring physicians of the existence of this specialised clinic.

Referred patients get appointments in a paediatrics clinic that does not have a waitlist. When the reason for referral is recurrent infection or suspected PID, patients are managed by paediatric specialists and a team of clinical immunologists.

There are limitations to our findings. Due to the retrospective nature of the analysis, there were incomplete data, as some variables were not documented in the records of some of the patients. Since the study was not multicentric, it contributes a particular perspective of the patients managed in a hospital with specific characteristics. Nevertheless, our findings reflect the increasing need for this type of clinic as a resource for paediatricians, so early and appropriate care can be offered to these children, thus reducing the associated morbidity.

Please cite this article as: Millán-Longo C, Rodríguez Molino P, del Rosal Rabes T, Corral Sánchez D, Méndez Echevarría A. Utilidad de una consulta especializada en inmunodeficiencias primarias. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;91:408–409.