In 2017, a worldwide survey was conducted on compliance with the practices promoted by Neo-BFHI (Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative expansion to neonatal wards).

ObjectiveTo present the results of the Spanish wards that participated in the global survey and compare them with those obtained internationally.

Material and methodsCross-sectional study through a survey on compliance with the Neo-BFHI (“Three basic principles”, “Ten steps adapted to neonatal wards” and “the compliance with the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes” and subsequent relevant World Health Assembly resolutions). Compliance was calculated as the mean in each indicator and a final mean score for each neonatal unit. For the partial and final scores for each country and at the international level, the median was used. All scores ranged between 0 and 100.

ResultsThe response rate in Spain was 90%. The range of the national mean for neonatal wards were from 37 to 99, with no differences in the final score according to the level of care. The global score for Spain (72) is below the international median (77) and this also occurs in 8 of 14 items. The neonatal wards from BFHI designated hospitals, obtained a significantly higher mean global score, and in 9 of 14 items than the non-accredited ones.

ConclusionsBoth international and national results indicate an improvement in breast feeding practices in neonatal units. The benefits of the BFHI accreditation of maternity reach neonatal wards. Spain has several key points below the international score.

En 2017 se realizó una encuesta a nivel mundial sobre el cumplimiento de las prácticas que promueve la Neo-IHAN (Iniciativa para la Humanización de la Asistencia al Nacimiento y la Lactancia en las unidades neonatales).

ObjetivoPresentar los resultados de las unidades españolas que participaron en la encuesta mundial y compararlos con los obtenidos internacionalmente.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal mediante una encuesta sobre el cumplimiento de los requisitos de la Neo-IHAN (“Tres principios básicos”, “Diez pasos adaptados a unidades neonatales” y “el Cumplimiento del Código Internacional de Comercialización de Sucedáneos de Leche Materna”). El cumplimiento se calculó como la media en cada indicador y una puntuación media final para cada unidad neonatal. Para las puntuaciones parciales y finales de cada país y a nivel internacional se utilizó la mediana. Las puntuaciones van de 0 a 100.

ResultadosLa tasa de respuesta en España fue del 90% de las unidades de nivel 2 y 3. El rango de la media para las unidades neonatales fue de 37 a 99, sin diferencias según el nivel asistencial. La puntuación global de España (72) está por debajo de la mediana internacional (77) así como en 8 de los 14 requisitos de la Neo-IHAN. Las unidades neonatales de hospitales con maternidades acreditadas IHAN, obtuvieron una puntuación media final significativamente mayor así como en 9 de los 14 requisitos frente a las no acreditadas.

ConclusionesLos resultados tanto internacionales como nacionales indican una mejora de las prácticas de la lactancia materna en las unidades neonatales. Los beneficios de la acreditación IHAN de las maternidades alcanzan a las unidades neonatales. España tiene varios puntos clave por debajo de la puntuación internacional.

In 2009, given the benefits of the introduction of the Initiative for the Humanization of Care at Birth and Lactation/Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) in maternity wards,1,2 health professionals in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland and Canada formed the Nordic and Quebec Working Group. The aim of the group was to expand the BFHI to neonatal wards, an initiative called Neo-IHAN. The group developed a series of documents based on evidence, expert opinion and clinical experience on the implementation of baby-friendly practices in relation to breastfeeding.3 These documents defined three “guiding principles” and adapted the “ten steps to successful breastfeeding” to the needs of neonatal wards. They also included compliance with the International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes (Code)4,5 (Table 1).

Neo-BFHI standards.

| The Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative for Neonatal Wards (Neo‐BFHI) | |

|---|---|

| Three guiding principles | |

| Guiding principle 1 | Staff attitudes towards the mother must focus on the individual mother and her situation |

| Guiding principle 2 | The facility must provide family‐centred care, supported by the environment |

| Guiding principle 3 | The health care system must ensure continuity of care from pregnancy to after the infant's discharge |

| Expanded Ten Steps to successful breastfeeding | |

| Step 1 | Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff |

| Step 2 | Educate and train all staff in the specific knowledge and skills necessary to implement this policy |

| Step 3 | Inform hospitalized pregnant women at risk for preterm delivery or birth of a sick infant about the benefits of breastfeeding and the management of lactation and breastfeeding |

| Step 4 | Encourage early, continuous and prolonged mother‐infant skin‐to‐skin contact/Kangaroo Mother Care |

| Step 5 | Show mothers how to initiate and maintain lactation, and establish early breastfeeding with infant stability as the only criterion |

| Step 6 | Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breast milk, unless medically indicated |

| Step 7 | Enable mothers and infants to remain together 24 h a day |

| Step 8 | Encourage demand breastfeeding or, when needed, semi‐demand feeding as a transitional strategy for preterm and sick infants |

| Step 9 | Use alternatives to bottle feeding at least until breastfeeding is well established, and use pacifiers and nipple shields only for justifiable reasons |

| Step 10 | Prepare parents for continued breastfeeding and ensure access to support services/groups after hospital discharge |

| Compliance with the International Code of Marketing of Breast‐milk Substitutes and relevant World Health Assembly resolutions (Code) | |

Later on, the World Health Organization published a document based on the work of the Nordic and Quebec Working Group, Baby-Friendly USA and PATH (a non-profit global health organization, http://www.path.org/about/flag/) on protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in small, sick and preterm newborns.6

The expansion of the BFHI to neonatal units is an opportunity to improve breastfeeding in the most vulnerable population that, until now, experienced the barrier of hospitalization and the separation from the mother that it implied. In 2017, Ragnhild Maastrup and Laura Haiek, members of the Nordic and Quebec Working Group, led a global survey to assess the degree of compliance with the practices promoted by the Neo-BFHI in neonatal wards. The aim of this study is to present the results for the Spanish units that participated in this survey and compare them to the results obtained at the international level.7

MethodsThe methods of the study have been described in a previous publication.7

The authors conducted a cross-sectional study in 36 countries using a self-appraisal questionnaire to assess compliance to the standards and criteria of the Neo-BFHI: the expansion with “three basic principles”, the “ten steps adapted to neonatal wards” and the “Code” (Table 1).

A survey leader was appointed in each participating country to be in charge of recruiting wards and following up on data collection. In Spain, the questionnaire was submitted to the neonatal wards of public hospitals included in the listing of the Ministry of Health that had been used for a previous survey.8

Compliance was measured by means of the “Cuestionario de autoevaluación Neo-BFHI” (Appendix 1), an adaptation of the self-appraisal tool included in the Neo-BFHI documentation, which was translated to Spanish and then validated.9 The Group recommended that the persons answering the questions be the best acquainted with breastfeeding and lactation practices in the ward. The data collection took place between February and December 2017. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of St. Mary’s Hospital Center in Quebec (reference number SMHC # 16–37). The invitation to participants clarified that answering the questionnaire implied consent to participate. Each neonatal ward was assigned a unique code to ensure confidentiality.

Survey methodologyThe outcomes used to determine compliance were based on the methodology previously used by Haiek.10 Most indicators were measured through a single statement. Nine were measured through more than 1 statement and the points attributed to the indicator were the mean of the points for each statement. Answers on a Likert scale (from “none” to “all” or “never” to “always”) were converted to 0-25-50-75-100 points. “Yes” answers were equivalent to 100 points and “No” or “Don’t know” answers to 0 points.

For each neonatal ward, compliance was calculated as the mean points obtained for each indicator of the three basic principles, ten steps and Code, giving rise to 14 partial scores per ward. All scores ranged from 0 to 100 points. The overall score of each neonatal ward was calculated as the mean of the partial scores.

Secondly, for each of the 36 countries, partial scores were calculated as the median of the partial scores of each neonatal ward. The country overall score was calculated as the median of the ward overall scores.

Lastly, the international partial scores were calculated as the median of the country partial scores, and the international overall score as the median of the overall scores of participating countries. The median was used instead of the mean for country and international scores because some countries had very few participating wards and others had score distributions that violated the assumption of normality.

A benchmark report was prepared for each neonatal ward presenting the results for their ward, their country, and international score for wards offering the same level of care. Each participating ward received the report comparing its outcomes with the median for Spain and the international median.

Statistical analysisWe have expressed the results as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR). In the comparative analysis of scores based on level of care or BFHI accreditation status, we used the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. We considered P values of less than 0.05 statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with the software SAS Enterprise Guide 8.2.

ResultsCharacteristics of the participantsSpain was the country with the highest number of participating neonatal units in the international study. The response rate was 90% (137/153). Fifteen level I units that had been previously considered level II units participated and were not included in the analysis.

Of the Spanish units that participated in the study, 8.2% (10/122) were in hospitals with BFHI-accredited maternity wards (2 level II hospitals, 8 level III hospitals) at the time of the survey. None of the neonatal units in Spain had received the Neo-BFHI accreditation, as it has yet to be introduced.

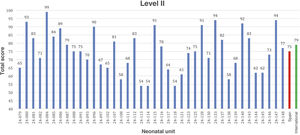

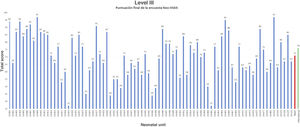

ScoresFigs. 1 and 2 present the overall mean for each level II and III unit in addition to the median in Spain and the international median. The mean score in neonatal units of any level in Spain ranged from 37 to 99.

We did not find significant differences in the overall scores between level II and level III neonatal units in Spain. We only found significant differences in guiding principle 2 (family-centred care): 85 (79–93) vs 79 (56–88), P = .028; step 8 (feeding on demand): 88 (71–99) vs 75 (65–88), P = .008, and step 9 (alternatives to bottle feeding): 80 (61–90) vs 63 (50−85), P = .019 (data expressed as median and interquartile range for level II vs III units).

The scores of Spanish level II and level III units were below the international median for neonatal wards of any level, both in the overall score and in 8.2% (10/122) of the 14 (62%) standards under study (Table 2).

Scores for Spanish units (levels II and III) and international units (any level of care).

| Median in Spain n = 122 | International median n = 917 | |

|---|---|---|

| Guiding principle 1: Staff attitudes towards the mother must focus on the individual mother and her situation | 88 (75−100) | 100 (88−100) |

| Guiding principle 2: the facility must provide family‐centred care | 81 (74−89) | 82 (73−88) |

| Guiding principle 3: the health care system must ensure continuity of care from pregnancy to after discharge | 83 (75−98) | 85 (79−92) |

| Step 1. Having a written breastfeeding policy | 75 (43−92) | 75 (54−88) |

| Step 2. Training all health care staff | 60 (45−83) | 76 (63−84) |

| Step 3. Informing pregnant women | 50 (25−88) | 63 (44−81) |

| Step 4. Kangaroo care | 82 (71−89) | 80 (64−84) |

| Step 5. Showing how to initiate and maintain breastfeeding | 82 (70−93) | 88 (80−90) |

| Step 6. Not giving other fluids | 88 (63−88) | 88 (75−88) |

| Step 7. Enabling rooming-in throughout stay | 67 (50−92) | 67 (58−100) |

| Step 8. Promoting breastfeeding on demand | 81 (63−94) | 81 (75−88) |

| Step 9. Alternatives to bottle feeding | 70 (50−85) | 78 (70−85) |

| Step 10. Facilitating post-discharge support | 75 (50−94) | 75 (69−81) |

| Code | 68 (50−82) | 84 (79−96) |

| Overall score | 72 (62−84) | 77 (72−81) |

Median and interquartile range (Q1-Q3).

Neonatal units in hospitals with BFHI-accredited maternity wards had a significantly higher mean overall score and significantly higher mean partial scores in 9 of the 14 standards (64%) compared to the rest of the units (Table 3).

Results of the survey on the Neo-BFHI standards.

| BFHI-accredited units (n = 10) | Units without BFHI accreditation (n = 112) | Statistical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guiding principle/step/code | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P |

| Guiding principle 1: Staff attitudes towards the mother must focus on the individual mother and her situation | 94 (10) | 87(13) | .354 |

| Guiding principle 2: the facility must provide family‐centred care | 86 (10) | 78 (14) | .170 |

| Guiding principle 3: the health care system must ensure continuity of care from pregnancy to after discharge | 91 (14) | 81 (17) | .239 |

| Step 1. Having a written breastfeeding policy | 100 (21) | 60 (37) | .006 |

| Step 2. Training all health care staff | 81 (18) | 61 (23) | .008 |

| Step 3. Informing pregnant women | 88 (24) | 53 (35) | .013 |

| Step 4. Kangaroo care | 89 (4) | 77 (16) | .005 |

| Step 5. Showing how to initiate and maintain breastfeeding | 90 (7) | 80 (15) | .065 |

| Step 6. Not giving other fluids | 82 (15) | 77 (20) | .532 |

| Step 7. Enabling rooming-in throughout stay | 92 (2) | 64 (23) | .005 |

| Step 8. Promoting breastfeeding on demand | 88 (7) | 75 (20) | .037 |

| Step 9. Alternatives to bottle feeding | 83 (12) | 66 (23) | .019 |

| Step 10. Facilitating post-discharge support | 94 (16) | 68 (24) | .024 |

| Code | 86 (22) | 64 (21) | .041 |

| Mean overall score | 97 (8) | 71 (14) | .001 |

SD, standard deviation.

The previous survey conducted in Spain to assess lactation and breastfeeding practices in neonatal units8 may have paved the way for this other survey, which would explain the substantial rate of participation in our country. Thanks to the 90% response rate, we have a comprehensive perspective of the current situation of breastfeeding practices in neonatal wards nationwide.

Our subanalysis of Spanish data on the degree of compliance with the Neo-BFHI recommendations in neonatal wards revealed that while the overall score in Spain (72) was below the international median (77), it was still a good starting point. The results evinced that substantial efforts have been made in Spain to improve breastfeeding and developmental care practices in neonatal wards. On the other hand, it helped identify aspects that need to be prioritised, including those related to step 2 (training health professionals), step 3 (informing pregnant women), step 7 (facilitating rooming-in during the stay), step 9 (providing alternatives to bottle feeding) and compliance with the Code.

The wide range of the scores in Spanish wards (37–99) suggests that there are still significant differences in the care provided to ill newborns depending on where they are hospitalised.

As for the influence of BFHI accreditation, in agreement with the findings of the international survey2 and the previous survey in Spain,8 we found that hospitals with BFHI accreditation exhibited greater adherence to the recommendations. The promotion and support of breastfeeding in the maternity ward seems to also have a positive effect on practices in neonatal wards.

The expansion of the “Ten Steps” for the BFHI accreditation of maternity wards contemplated by the Neo-BFHI, including the three basic principles, addresses the support needs of mothers with preterm or ill newborns at a very vulnerable point in their lives.11 These guiding principles define general principles and attitudes that are essential to every aspect of lactation and breastfeeding in neonatal wards.

Guiding principle 1 calls for respect and empathy in maternal care. Maternal motivation to establish lactation and breastfeeding improves if support is provided with empathy and respecting cultural differences.12,13 The score obtained in Spain, 12 points under the international score, evinces the need to improve communication skills at this juncture in which the family is particularly vulnerable.14

Guiding principle 2 refers to the provision of developmental and family-centred care supported by the environment. The parents are the most important individuals in the life of the child and should be encouraged to act as the primary caregivers of the newborn. An open-door policy, 24 h a day, 7 days a week, is already established in wards in Spain. Training on developmental care in the neonatal ward setting, in addition to involving the family in the care of the infant, has helped improve this aspect.15–21 Level II units performed better in this principle. Perhaps the lower complexity and lower occupancy rates of these units facilitate caring for families in a more favourable environment.

Guiding principle 3 calls for guaranteeing continuity of care from pregnancy to after the infant's discharge.22–24 In Spain, the public health system guarantees care for all pregnant women regardless of their administrative status, in addition to childbirth services and neonatal care. The primary care system in Spain has paediatricians to ensure the optimal follow-up of the paediatric population. The score obtained in this principle was similar to the international median.

In the analysis of the ten steps, we found national medians that were equal to or less than the international median for step 1 (written breastfeeding policy), step 2 (training of all health care staff) and step 3 (informing pregnant women). The scores were significantly better in BFHI-accredited hospitals. The initiation and maintenance of the breast milk supply is essential for mothers to be able to breastfeed hospitalised newborns. Adequate training of health care professionals is of the essence.25

Step 4 (kangaroo care) was the only step in which the median in Spain was better compared to the international median (82 vs 80). Once again, the score was better in hospitals with BFHI-accredited maternity wards. Gradually, kangaroo care has been extended to patients with increasingly severe disease admitted to intensive care units.26–32 It has also been proven safe during the performance of procedures, helping tolerate them better and contributing to the stability of the infant.33 By helping establish breastfeeding earlier, kangaroo care could shorten the length of stay, reducing inpatient care costs and benefitting families. Comparing the current results with those of the survey performed in 2012,27 we found more widespread implementation of kangaroo care in Spain.

In Step 5 (show mothers how to initiate and maintain lactation) and Step 6 (give infants no fluids but breast milk), the scores in Spain were similar to the international median. These steps involve early support of mothers for establishing breastfeeding, with early and frequent breast milk expression.34,35 The availability of donor human milk as an alternative when mother’s own milk is not available is another aspect that has improved in Spain in the past 10 years. New human milk banks have been created in strategic geographical locations to provide access to the largest possible number of patients. There is evidence that the availability of donor human milk increases the rate of breastfeeding with mother’s own milk in neonatal wards.36

Step 7 (enable rooming-in) is an extreme point in which not even international scores exceeded 75 points. The difficulty enabling rooming-in mainly stems from architectural, economic, cultural and social barriers. Although in recent years there have been improvements in maternity leave for preterm and ill newborns in Spain, awareness needs to be raised among hospital architects, administrators and managers to change the currently dominant neonatal unit model of hospitalization in open-bay layouts without beds for the mothers. Single-family rooms, already set up in some hospitals in Spain, promote breastfeeding in preterm infants as well as bonding and parental autonomy.37–39 The humanization of care and perceived quality of care targets that have been set will help advance in this area.

In Step 8 (encourage demand breastfeeding or semi‐demand feeding as a transitional discharge strategy) and Step 9 (use alternatives to bottle feeding at least until breastfeeding is well established, and use pacifiers and nipple shields only for justifiable reasons), Spanish units scored the same or below the international median. Units in BFHI-accredited hospitals and level II units scored better in these steps. Breastfeeding on demand is affected by improvements in unit infrastructure that allow rooming-in with meals provided by the hospital and workplace and social improvements allowing mothers to spend more time with their newborns.40 The use of feeding methods other than bottle feeding depends on the individual characteristics of the patient, the availability of the parents and the training of health professionals. There is evidence that bottle feeding has a negative impact on breastfeeding in both term41 and preterm newborns,42 while cup feeding is associated with higher rates of breastfeeding at discharge.43 The stability of the newborn should be the sole criterion for breastfeeding initiation.44

In Step 10 (facilitate breastfeeding support after discharge), the results were the same in Spain as internationally, with better scores in BFHI-accredited hospitals. The important role of lactation consultants and support groups may be reflected in these results. The most vulnerable period for breastfeeding in preterm or ill infants is the first month after discharge. Support after discharge through telemedicine or breastfeeding peer counsellors has proven beneficial.45,46

Last of all, as pertains the Code, the score at the national level was very low (68) compared to the international median (84). This score was also significantly better in units in BFHI-accredited hospitals, as it is a requisite for accreditation and reflects the close association between the maternity ward and neonatal care units. Training in ethics and how to manage relationships the companies that distribute milk substitutes to avoid violations of the code during medical education or in the residency period is particularly important.47,48 Actions that violate the Code have a negative impact on breastfeeding and therefore on the health of women and children.49,50

The high response rate from Spanish units and the consistency with the findings of other studies8,17 are among the strengths of the study. Its limitations include those intrinsic to questionnaire-based surveys without auditing of actual practices where reports of health professionals are the sole source of information. Another aspect to consider is the weight that level I units in Spain may have had in international results compared to results of level II and level III units in Spain.

Lastly, it is reasonable to conclude that the findings in Spain and internationally are promising and reflect a concern with breastfeeding practices on the part of neonatal units to ensure availability of breast milk for all ill newborns and that mothers feels supported in breastfeeding. Some aspects in which Spain performed poorly, such as the information given to pregnant women, the training of health care staff or compliance with the Code, call for specific action with involvement of multiple professionals and changes to the culture of neonatal wards. Improving the coordination of care from neonatal units in relation to the initial visit to the primary care paediatrician is of the essence, especially in complex cases or when biological risks are compounded by social risks. On the other hand, we found substantial differences between units, and efforts should be made to bridge the gap and ensure equity in the care delivered in neonatal units throughout Spain.

ConclusionOutcomes at both the international and the domestic levels are progressing toward the improvement of lactation and breastfeeding practices in neonatal wards. The results in Spain are satisfactory overall and demonstrate that the benefits of BFHI accreditation of maternity wards extend to the neonatal units, while aspects remain that could be significantly improved. The creation of the Neo-BFHI or the extension of the BFHI to neonatal wards is an efficacious and high-quality tool aimed at improving lactation and breastfeeding practices in the most vulnerable newborns.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Cabrera-Lafuente M, Alonso-Díaz C, Moral Pumarega MT, Díaz-Almirón M, Haiek LN, Maastrup R, et al., Prácticas de lactancia materna en las unidades neonatales de España. Encuesta internacional Neo-IHAN, Anales de Pediatría. 2022;96:300–308.